Space, Place and Memory in Early Colonial Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Convict Labour and Colonial Society in the Campbell Town Police District: 1820-1839

Convict Labour and Colonial Society in the Campbell Town Police District: 1820-1839. Margaret C. Dillon B.A. (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph. D.) University of Tasmania April 2008 I confirm that this thesis is entirely my own work and contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. Margaret C. Dillon. -ii- This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Margaret C. Dillon -iii- Abstract This thesis examines the lives of the convict workers who constituted the primary work force in the Campbell Town district in Van Diemen’s Land during the assignment period but focuses particularly on the 1830s. Over 1000 assigned men and women, ganged government convicts, convict police and ticket holders became the district’s unfree working class. Although studies have been completed on each of the groups separately, especially female convicts and ganged convicts, no holistic studies have investigated how convicts were integrated into a district as its multi-layered working class and the ways this affected their working and leisure lives and their interactions with their employers. Research has paid particular attention to the Lower Court records for 1835 to extract both quantitative data about the management of different groups of convicts, and also to provide more specific narratives about aspects of their work and leisure. -

26 January (Australia Day)

What does 26 January mean to you? A day off, a barbecue and fireworks? A celebration of who we are as a nation? A day of mourning and invasion? A celebration of survival? Australians hold many different views on what 26 January means to them. For many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, it isn't a day for celebration. Instead, 26 January represents a day on which their way of life was invaded and changed forever. For others, it is Survival Day, and a celebration of the survival of people and culture, and the continuous contributions Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people make to Australia. On the eve of 26 January, and in the spirit of reconciliation, we would like to recognise these differences and ask you to reflect on how we can create a day all Australians can celebrate. On this day in… From around 40,000 BC the continuing culture and traditions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples flourishes across the country. 1788 The First Fleet lands on Australian shores, and Captain Phillip raises the Union Jack as a symbol of British occupation.1 1818 26 January is first recognised as a public holiday in NSW to mark the 30th anniversary of British settlement.2 1938 Re-enactments of the First Fleet landing are held in Sydney, including the removal of a group of Aboriginal people. This practice of re-enactment continued until 1988, when the NSW government demanded it stop.3 1 http://www.australiaday.org.au/australia-day/history/timeline/ 2 http://www.australiaday.org.au/australia-day/history/timeline/ 3 http://www.australiaday.com.au/about/history-of-australia-day/1889-1938-2/#.UsT1GtIW3bM 1938 Aboriginal activists hold a ‘Day of Mourning’ aimed at securing national citizenship and equal status for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.4 1968 Lionel Rose becomes the first Aboriginal Australian to be named Australian of the Year. -

Issue 31, June 2019

From the President I recently experienced a great sense of history and admiration for early Spanish and Portuguese navigators during visits to historic sites in Spain and Portugal. For example, the Barcelona Maritime Museum, housed in a ship yard dating from the 13th century and nearby towering Christopher Columbus column. In Lisbon the ‘Monument to the Discoveries’ reminds you of the achievements of great explorers who played a major role in Portugal's age of discovery and building its empire. Many great navigators including; Vasco da Gama, Magellan and Prince Henry the Navigator are commemorated. Similarly, in Gibraltar you are surrounded by military and naval heritage. Gibraltar was the port to which the badly damaged HMS Victory and Lord Nelson’s body were brought following the Battle of Trafalgar fought less than 100 miles to the west. This experience was also a reminder of the exploits of early voyages of discovery around Australia. Matthew Flinders, to whom Australians owe a debt of gratitude features in the June edition of the Naval Historical Review. The Review, with its assessment of this great navigator will be mailed to members in early June. Matthew Flinders grave was recently discovered during redevelopment work on Euston Station in London. Similarly, this edition of Call the Hands focuses on matters connected to Lieutenant Phillip Parker King RN and his ship, His Majesty’s Cutter (HMC) Mermaid which explored north west Australia in 1818. The well-known indigenous character Bungaree who lived in the Port Jackson area at the time accompanied Parker on this voyage. Other stories in this edition are inspired by more recent events such as the keel laying ceremony for the first Arafura Class patrol boat attended by the Chief of Navy. -

Phanfare May/June 2006

Number 218 – May-June 2006 Observing History – Historians Observing PHANFARE No 218 – May-June 2006 1 Phanfare is the newsletter of the Professional Historians Association (NSW) Inc and a public forum for Professional History Published six times a year Annual subscription Email $20 Hardcopy $38.50 Articles, reviews, commentaries, letters and notices are welcome. Copy should be received by 6th of the first month of each issue (or telephone for late copy) Please email copy or supply on disk with hard copy attached. Contact Phanfare GPO Box 2437 Sydney 2001 Enquiries Annette Salt, email [email protected] Phanfare 2005-06 is produced by the following editorial collectives: Jan-Feb & July-Aug: Roslyn Burge, Mark Dunn, Shirley Fitzgerald, Lisa Murray Mar-Apr & Sept-Oct: Rosemary Broomham, Rosemary Kerr, Christa Ludlow, Terri McCormack, Anne Smith May-June & Nov-Dec: Ruth Banfield, Cathy Dunn, Terry Kass, Katherine Knight, Carol Liston, Karen Schamberger Disclaimer Except for official announcements the Professional Historians Association (NSW) Inc accepts no responsibility for expressions of opinion contained in this publication. The views expressed in articles, commentaries and letters are the personal views and opinions of the authors. Copyright of this publication: PHA (NSW) Inc Copyright of articles and commentaries: the respective authors ISSN 0816-3774 PHA (NSW) contacts see Directory at back of issue PHANFARE No 218 – May-June 2006 2 Contents At the moment the executive is considering ways in which we can achieve this. We will be looking at recruiting more members and would welcome President’s Report 3 suggestions from members as to how this could be Archaeology in Parramatta 4 achieved. -

Winter 2012 SL

–Magazine for members Winter 2012 SL Olympic memories Transit of Venus Mysterious Audubon Wallis album Message Passages Permanence, immutability, authority tend to go with the ontents imposing buildings and rich collections of the State Library of NSW and its international peers, the world’s great Winter 2012 libraries, archives and museums. But that apparent stasis masks the voyages we host. 6 NEWS 26 PROVENANCE In those voyages, each visitor, each student, each scholar Elegance in exile Rare birds finds islets of information and builds archipelagos of Classic line-up 30 A LIVING COLLECTION understanding. Those discoveries are illustrated in this Reading hour issue with Paul Brunton on the transit of Venus, Richard Paul Brickhill’s Biography and Neville on the Wallis album, Tracy Bradford on our war of nerves business collections on Olympians such as Shane Gould and John 32 NEW ACQUISITIONS Konrads, and Daniel Parsa on Audubon’s Birds of America, Library takes on Vantage point one of our great treasures. Premier’s awards All are stories of passage, from Captain James Cook’s SL French connection Art of politics voyage of geographical and scientific discovery to Captain C THE MAGAZINE FOR STATE LIBRARY OF NSW BUILDING A STRONG ON THIS DAY 34 FOUNDATION MEMBERS, 8 James Wallis’s album that includes Joseph Lycett’s early MACQUARIE STREET FRIENDS AND VOLUNTEERS FOUNDATION Newcastle and Sydney watercolours. This artefact, which SYDNEY NSW 2000 IS PUBLISHED QUARTERLY 10 FEATURE New online story had found its way to a personal collection in Canada, BY THE LIBRARY COUNCIL PHONE (02) 9273 1414 OF NSW. -

Parramatta's Archaeological Landscape

Parramatta’s archaeological landscape Mary Casey Settlement at Parramatta, the third British settlement in Australia after Sydney Cove and Norfolk Island, began with the remaking of the landscape from an Aboriginal place, to a military redoubt and agricultural settlement, and then a township. There has been limited analysis of the development of Parramatta’s landscape from an archaeological perspective and while there have been numerous excavations there has been little exploration of these sites within the context of this evolving landscape. This analysis is important as the beginnings and changes to Parramatta are complex. The layering of the archaeology presents a confusion of possible interpretations which need a firmer historical and landscape framework through which to interpret the findings of individual archaeological sites. It involves a review of the whole range of maps, plans and images, some previously unpublished and unanalysed, within the context of the remaking of Parramatta and its archaeological landscape. The maps and images are explored through the lense of government administration and its intentions and the need to grow crops successfully to sustain the purposes of British Imperialism in the Colony of New South Wales, with its associated needs for successful agriculture, convict accommodation and the eventual development of a free settlement occupied by emancipated convicts and settlers. Parramatta’s river terraces were covered by woodlands dominated by eucalypts, in particular grey box (Eucalyptus moluccana) and forest -

LAYING CLIO's GHOSTS on the SHORES of NEW HOLLAND* the Title Does Not Foreshadow an Ex

EMPTY HISTORICAL BOXES OF THE EARLY DAYS: LAYING CLIO'S GHOSTS ON THE SHORES OF NEW HOLLAND* By DUNCAN ~T ACC.ALU'M HE title does not foreshadow an exhumation of the village Hampdens, as Webb T called them,! buried on the shores of Botany Bay. In fact, they were probably thieves, but let their ;-emains rest in peace. No, the metaphor in the title is from an analogy from a memorable controversy in value theory in Economics. 2 The title was meant to suggest the need for giving some historical content to the emotions that have accompanied discussions of the early period. Some of the figures which seem to have been conjured up by historical writers have been given malignancy but 110t identity. Yet these faceless men of the past, and the roles for which they have been cast, seem to distort the play of life. And indeed, it is perhaps because the historical boxes have remained unfilled, and because the background-the rest of the play and action-has not been fully explored, that some people of the early period, well known to us by name, have been interpreted in the light of twentieth-century prejudice and political controversy. We know all too little about the quality of day-to-day life in early Australia, the spiritual and material existence of the early Europeans, their energies, their activities and outlook. In the first stage of an inquiry I have been pursuing into our early social history, I am concerned not with these more elusive yet in a way more interesting questions, but in what sort of colony it was with the officers, the gaol and the port. -

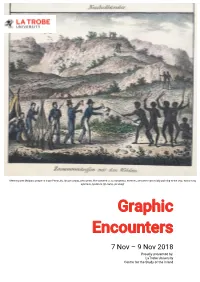

Graphic Encounters Conference Program

Meeting with Malgana people at Cape Peron, by Jacque Arago, who wrote, ‘the watched us as dangerous enemies, and were continually pointing to the ship, exclaiming, ayerkade, ayerkade (go away, go away)’. Graphic Encounters 7 Nov – 9 Nov 2018 Proudly presented by: LaTrobe University Centre for the Study of the Inland Program Melbourne University Forum Theatre Level 1 Arts West North Wing 153 148 Royal Parade Parkville Wednesday 7 November Program 09:30am Registrations 10:00am Welcome to Country by Aunty Joy Murphy Wandin AO 10:30am (dis)Regarding the Savages: a short history of published images of Tasmanian Aborigines Greg Lehman 11.30am Morning Tea 12.15pm ‘Aborigines of Australia under Civilization’, as seen in Colonial Australian Illustrated Newspapers: Reflections on an article written twenty years ago Peter Dowling News from the Colonies: Representations of Indigenous Australians in 19th century English illustrated magazines Vince Alessi Valuing the visual: the colonial print in a pseudoscientific British collection Mary McMahon 1.45pm Lunch 2.45pm Unsettling landscapes by Julie Gough Catherine De Lorenzo and Catherine Speck The 1818 Project: Reimagining Joseph Lycett’s colonial paintings in the 21st century Sarah Johnson Printmaking in a Post-Truth World: The Aboriginal Print Workshops of Cicada Press Michael Kempson 4.15pm Afternoon tea and close for day 1 2 Thursday 8 November Program 10:00am Australian Blind Spots: Understanding Images of Frontier Conflict Jane Lydon 11:00 Morning Tea 11:45am Ad Vivum: a way of being. Robert Neill -

CONCLUSION This Literary Study and Close Account of Her Social

224 CONCLUSION This literary study and close account of her social philosophy has demonstrated that the novelist, Eleanor Dark, was also a vigorous social protester and moralist, both concerned with pressing contemporary problems and with their psychological origins, and bent on showing in her fiction a close connection between political forces and individual lives. It has been made clear in this critical treatment .:hat, with a romantics revolutionary turn of mind, she was determined to open her readers eyes to so many social injustices. These were all too often perpetrated by mediocre leaders, and yet the people, in their ignorance and apathy, were hardly aware of them. To illustrate this she created a series of idealistic, independently thinking characters who set out to right social wrongs by exercising heroic personal integrity, by being true to their own consciences, and by establishing ideals which would enrich, rather than constrict, both the individual and society as a whole. The study has shown, however, that Dark always emphasised the need to put theory into action, and to curb simplistic idealism with a measure of lived practicality. There was presented in Chapter 2 the writers perception of human existence as a progression or journey, with her questing protagonists energetically engaging with all aspects of life as they struggled toward the goal of social harmony and the desired realisation of personal potential. Throughout, there has been critical emphasis upon the novels impressive celebration of life, and I have endeavoured to show that the vitality of Darks daring protagonists became a means of judging the behaviour of others, as she contrasted them with those lesser and more timid characters who refused Ito participate willingly in the mortal contest. -

Macquarie University Researchonline

Macquarie University ResearchOnline This is the author’s version of an article from the following conference: Walsh, Robin (2008) Pixels & Partnerships: digital publishing and co- operative scholarship in Australian and British imperial history. Digital discoveries : strategies and solutions : 29th annual conference of the Association of Technological University Libraries, (21 - 24 April 2008, Auckland) Access to the published version: http://www.iatul.org/doclibrary/public/Conf_Proceedings/2008/RWalsh 080318.doc Title Pixels & Partnerships: digital publishing and co-operative scholarship in Australian and British imperial history. Author Robin Walsh Macquarie University Library Sydney NSW 2109 Australia Contact Details [email protected] www.lib.mq.edu.au/digital/lema Abstract The efforts of libraries and archival institutions in collecting and curating dispersed collections of original letters, journals, pictorial sources, and realia/artefacts are essential contributions towards research and scholarship. Recent technological advances in digitization offer important new possibilities in the reproduction of documents and images as well as enhanced access to dispersed institutional holdings. The Lachlan & Elizabeth Macquarie Archive (LEMA) is a co-operative inter-institutional website project based at Macquarie University Library, in partnership with key Australian and UK institutions. The aim of the LEMA Project is to create a digital research gateway to the writings of the Lachlan Macquarie (1761-1824), governor of New South Wales from 1810- 1821 and his wife Elizabeth (1778-1835), and thereby assist in the study and analysis of their place in Australian and imperial history. The LEMA framework is designed to explore the personal and global contexts of the Macquaries through the use of full-text transcriptions of documentary sources, as well as contributing towards the identification and digital repatriation of personal objects associated with their lives. -

13.0 Remaking the Landscape

12 Chapter 13: Remaking the Landscape 13.0 Remaking the landscape 13.1 Research Question The Conservatorium site is located within one of the most significant historic and symbolic landscapes created by European settlers in Australia. The area is located between the sites of the original and replacement Government Houses, on a prominent ridge. While the utility of this ridge was first exploited by a group of windmills, utilitarian purposes soon became secondary to the Macquaries’ grandiose vision for Sydney and the Governor’s Domain in particular. The later creations of the Botanic Gardens, The Garden Palace and the Conservatorium itself, re-used, re-interpreted and created new vistas, paths and planting to reflect the growing urban and economic importance of Sydney within the context of the British empire. Modifications to this site, its topography and vegetation, can therefore be interpreted within the theme of landscape as an expression of the ideology of colonialism. It is considered that this site is uniquely placed to address this research theme which would act as a meaningful interpretive framework for archaeological evidence relating to environmental and landscape features.1 In response to this research question evidence will be presented on how the Government Domain was transformed by the various occupants of First Government House, and the later Government House, during the first years of the colony. The intention behind the gathering and analysis of this evidence is to place the Stables building and the archaeological evidence from all phases of the landscape within a conceptual framework so that we can begin to unravel the meaning behind these major alterations. -

Matthew Flinders: Pathway to Fame

INTERNATIONAL HYDROGRAPHIC REVIEW VoL. 2 No. 1 {NEW SERIES) JUNE 2001 Matthew Flinders: Pathway to Fame joe Doyle Since his death many books and articles have been written about Matthew Flinders . During his life, apart from his own books, he wrote much himself, and there is a large body of contemporary correspondence concerning him in various archives in England and Australia. The bicentenary of the start of his voyage in Investigator is so important that it deserves once more, to be drawn to the atten tion of those interested in hydrography. This paper traces Matthew Flinders' early life and training as a hydrographer until July 1801 when he sailed from England in Investigator on his fateful mission to chart the little known southern continent, that land mass which had yet to be named Australia. Introduction An niversaries of two milestones of 'European ' Austral ia occur in 2001. The sig nificant event is the centenary of the formation of the Commonwealth of Australi a. It is also the bicentenary of the start of an important British voyage to complete the survey of that continent and from which the term Australia began to be accept ed as the name for the country. July 2001 is the 200th anniversary of the departure from Spithead of Investigator, a sloop' fitted out and stored for a voyage to remote parts. The vessel, under the command of Commander Matthew Flinders, Royal Navy, was bound for New South Wales, a colony established thirteen years earlier. The purpose of the voyage was to make a complete examination and survey of the coast of that island continent.