Christian Zionism" in Battleground Religion, Ed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Christian Zionist Lobby and U.S.-Israel Policy

University of South Florida Digital Commons @ University of South Florida Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 6-25-2010 The Christian Zionist Lobby and U.S.-Israel Policy Mark G. Grzegorzewski University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Grzegorzewski, Mark G., "The Christian Zionist Lobby and U.S.-Israel Policy" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd/3671 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Christian Zionist Lobby and U.S.-Israel Policy by Mark G. Grzegorzewski A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Government and International Affairs College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Mark Amen, Ph.D. Michael Solomon, Ph.D. Abdelwahab Hechiche, Ph.D. Date of Approval: June 25, 2010 Keywords: Israel, Road Map, Unilateralism, United States, Christian Zionists Copyright © 2010, Mark G. Grzegorzewski DEDICATION For my beautiful daughter, Riley Katelyn. Without the joy you bring to my life I never would have continued to pursue my academic goals. Your very being provides me with the inspiration to make the world a better place for you to grow up in. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like thank Dr. -

Jews and Christians: Perspectives on Mission the Lambeth-Jewish Forum

Jews and Christians: Perspectives on Mission The Lambeth-Jewish Forum Reuven Silverman, Patrick Morrow and Daniel Langton Jews and Christians: Perspectives on Mission The Lambeth-Jewish Forum Both Christianity and Judaism have a vocation to mission. In the Book of the Prophet Isaiah, God’s people are spoken of as a light to the nations. Yet mission is one of the most sensitive and divisive areas in Jewish-Christian relations. For Christians, mission lies at the heart of their faith because they understand themselves as participating in the mission of God to the world. As the recent Anglican Communion document, Generous Love, puts it: “The boundless life and perfect love which abide forever in the heart of the Trinity are sent out into the world in a mission of renewal and restoration in which we are called to share. As members of the Church of the Triune God, we are to abide among our neighbours of different faiths as signs of God’s presence with them, and we are sent to engage with our neighbours as agents of God’s mission to them.”1 As part of the lifeblood of Christian discipleship, mission has been understood and worked out in a wide range of ways, including teaching, healing, evangelism, political involvement and social renewal. Within this broad and rich understanding of mission, one key aspect is the relation between mission and evangelism. In particular, given the focus of the Lambeth-Jewish Forum, how does the Christian understanding of mission affects relations between Christianity and Judaism? Christian mission and Judaism has been controversial both between Christians and Jews, and among Christians themselves. -

PHILOLOGIA ARTS & Vol

COLLEGE OF LIBERALPHILOLOGIA ARTS & Vol. X HUMAN SCIENCES Undergraduate Research Journal Associate Editor: Holly Hunter Faculty Reviewer: Shaily Patel Author: Rachel Sutphin Title: The Impact of Christianity on Israel-Palestine Peace Relations ABSTRACT When analyzing the Israel-Palestine conflict, one may be tempted to focus solely on the political and historical situation of the geographic land. However, it is also important to consider the deeply embedded religious traditions of the area. When doing so, one will come across Christian Zionism, an impediment to peace. Some of the most prominent voices find validation for their narratives and actions through Christian Zionism. Zionism, in all forms, is an ideology that anchors Jews to Eretz Yisrael, the land of Biblical Israel. Some forms of Zionism include a system of balancing accumulations of land, resources, and wealth with the displacement of Palestinians. This belief that the Jews have a divineVOL. right to the X accumulation of land and resources legitimizes Zionism in their conquering of the past-legitimate Palestine. Thus, as Palestinian scholar Edward Said states, Zionism is an imported ideology in which Palestinians “pay and suffer” (Said, 1978). Christian Zionism consists of a variety of beliefs that promote and protect the Israeli state and government, while also dehumanizing the Palestinians and equating anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism. As a result, Christian Zionism is a challenging obstacle, one that is necessary to overcome to establish peace. Therefore, due to Christians being called to live peacefully (Colossians 3:15), the Christian tradition must seek and adhere to an alternative theology to Christian Zionism. Palestinian Christian Liberation Theology is a relevant way to interpret Scriptures based on the Christian tradition of peace found in the Old and New Testaments. -

Jewish Culture in the Christian World James Jefferson White University of New Mexico - Main Campus

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 11-13-2017 Jewish Culture in the Christian World James Jefferson White University of New Mexico - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation White, James Jefferson. "Jewish Culture in the Christian World." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/207 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. James J White Candidate History Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Sarah Davis-Secord, Chairperson Timothy Graham Michael Ryan i JEWISH CULTURE IN THE CHRISTIAN WORLD by JAMES J WHITE PREVIOUS DEGREES BACHELORS THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December 2017 ii JEWISH CULTURE IN THE CHRISTIAN WORLD BY James White B.S., History, University of North Texas, 2013 M.A., History, University of New Mexico, 2017 ABSTRACT Christians constantly borrowed the culture of their Jewish neighbors and adapted it to Christianity. This adoption and appropriation of Jewish culture can be fit into three phases. The first phase regarded Jewish religion and philosophy. From the eighth century to the thirteenth century, Christians borrowed Jewish religious exegesis and beliefs in order to expand their own understanding of Christian religious texts. -

The Role of Ultra-Orthodox Political Parties in Israeli Democracy

Luke Howson University of Liverpool The Role of Ultra-Orthodox Political Parties in Israeli Democracy Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy By Luke Howson July 2014 Committee: Clive Jones, BA (Hons) MA, PhD Prof Jon Tonge, PhD 1 Luke Howson University of Liverpool © 2014 Luke Howson All Rights Reserved 2 Luke Howson University of Liverpool Abstract This thesis focuses on the role of ultra-orthodox party Shas within the Israeli state as a means to explore wider themes and divisions in Israeli society. Without underestimating the significance of security and conflict within the structure of the Israeli state, in this thesis the Arab–Jewish relationship is viewed as just one important cleavage within the Israeli state. Instead of focusing on this single cleavage, this thesis explores the complex structure of cleavages at the heart of the Israeli political system. It introduces the concept of a ‘cleavage pyramid’, whereby divisions are of different saliency to different groups. At the top of the pyramid is division between Arabs and Jews, but one rung down from this are the intra-Jewish divisions, be they religious, ethnic or political in nature. In the case of Shas, the religious and ethnic elements are the most salient. The secular–religious divide is a key fault line in Israel and one in which ultra-orthodox parties like Shas are at the forefront. They and their politically secular counterparts form a key division in Israel, and an exploration of Shas is an insightful means of exploring this division further, its history and causes, and how these groups interact politically. -

The Church and the Jews

PAMPHLET NO. 26 The Church and the Jews A Memorial Issued by Catholic European Scholars PBICE 10 CENTS THE CATHOLIC ASSOCIATION FOR INTERNATIONAL PEACE 1312 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D. C. HPHIS study, which has been translated from the German by the Reverend Dr. Gregory Feige, is being issued as a report of the Committee on National Attitudes. NATIONAL ATTITUDES COMMITTEE Chairman CARLTON J. H. HAYES Vice-Chairmen REV. JOHN LaFARGE, S.J. GEORGE N. SHUSTER Herbert C. F. Bell Sara E. Lauchlin Frances S. Childs Elizabeth M. Lynskey Rev. John M. Cooper Milo F. McDonald Rev. Gregory Feige Georgiana P. McEntee Rev. Adolph D. Frenay, O.P. Rev. R. A. McGowan Rev. Francis J. Gilligan Francis E. McMahon Rev. E. P. Graham Rev. T. Lawrason Riggs D. L. Maynard Gray Rev. Maurice S. Sheehy Ellamay Horan Sister M. Immaculata, I.H.M. Maurice Lavanoux Sister Mary Vincent Sister ] Alacoque THE CHURCH AND THE JEWS A Memorial Issued by Catholic European Scholars English Version by Reverend Dr. Gregory Feige Published by The Committee on National Attitudes of THE CATHOLIC ASSOCIATION FOR INTERNATIONAL PEACE 1312 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D. C. THE PAULIST PRESS 401 West 59th Street New York, N. Y. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Preface 4 Theological Principles and the Jewish Question of Today: Is Yahwe a Jewish God or Is Israel God’s People? 5 Was Jesus the First Anti-Semite or the True Jew?.... 9 Is Israel Eternally Damned or Reserved for Salva¬ tion? 12 Anti-Semitism in the Judgment of the Church 14 The Political and Practical Side of -

Global Jewish Forum Haredim and the Jewish Collective: Engaging with Voices from the Field

Global Jewish Forum Haredim and the Jewish Collective: Engaging with Voices from the Field Presented by Makom 27 th February, 2012 - 4 Adar I, 5772 For internal educational use only Printed at the Jewish Agency 1 Table of Contents The Back Story • What is Orthodoxy? Samuel C. Heilman and Menachem Friedman, The Haredim in Israel • Zionism and Judaism From The Jewish Political Tradition Volume 1 Authority (2000) • The “Status Quo” and David Ben Gurion From the Jewish Agency for Israel to Agudat Yisrael 19th June, 1947 • Israelis and Religion Professor Michael Rosenak, from The Land of Israel: Its contemporary meaning (1992) • A different approach Jeri Langer, from The Jew in the Modern World (1995) Statistics and Policies • Demographics …………………………………………………………………………………………. 5 • Education ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 • Army ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 • Work ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 7 Israel 5772 – so far • Risking one’s life on the bus ……………………………………………………………………… 10 • A civil war no one wants …………………………………………………………………………. 14 • Statement from Agudath Israel of America ……………………………………………….. 16 • Gender Trouble ………………………………………………………………………………………. 17 • Haredi leaders must speak out against zealots ………………………………………….. 20 • Lessons from Bet Shemesh ………………………………………………………………………. 22 • The remarkable good news about the Haredim …………………………………………. 26 2 Global Jewish Forum A biennial event for deep consideration of the pressing issues of the Jewish People… Moving beyond the communal headlines to examine the deep issues that drive them... International Jewish leaders deliberately not taking decisions, but together deciding to deliberate... Young committed adults sit around the table with institutional leaders, sharing perspectives and gaining understanding. Welcome to the 2 nd Global Jewish Forum. At the inaugural Forum last June the Makom team presented a day that explored the intra-communal challenges of the fight against delegitimation. -

A Public Dialogue: Contemporary Questions About Covenant(S) and Conversion Edward Kessler, the Woolf Institute of Abrahamic Faiths, Cambridge University Philip A

Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations Volume 4 (2009): Kessler/Cunningham CP1-15 CONFERENCE PROCEEDING A Public Dialogue: Contemporary Questions about Covenant(s) and Conversion Edward Kessler, The Woolf Institute of Abrahamic Faiths, Cambridge University Philip A. Cunningham, Jewish-Catholic Institute, St. Joseph’s University Presented at St. Joseph’s University, January 11, 2009 In recent years, several controversies have beset official relations between Jews and Catholics. These include whether Catholics should pray for the conversion of Jews, whether the purpose of interreligious dialogue is to lead others to Christian faith, and whether Catholics should undertake non-coercive "missions" to Jews. An underlying theological topic in all these disputes is how the biblical concept of "covenant" is understood in the Jewish and Catholic traditions and in terms of their interrelationship. The resolution of these questions could set the pattern of official Catholic-Jewish relations for many years. In a public dialogue of these matters, Dr. Edward Kessler from Cambridge University in Great Britain and Dr. Philip A. Cunningham, Director of the Jewish-Catholic Institute at St. Joseph’s University presented and discussed their own analyses of the present situation. Link to video at: http://model.inventivetec.com/inventivex/mediaresources/checkout_clean.cfm?ContentID =28893&TransactionID=218605&Checksum=%20%20509780&RepServerID=&JumpSec onds=0&CFID=3895491&CFTOKEN=14161271 Covenant, Mission and Dialogue Edward Kessler Covenant, mission and dialogue illustrate both the extent of the common ground between Jews and Christians and also many of the difficulties that still need to be addressed. The challenge they bring is demonstrated by Nostra Aetate, perhaps the most influential of the recent church documents on Jewish–Christian relations. -

Language Diversity in Israel & Palestine Human Footprint

The reason for Israel’s language diversity is LANGUAGE DIVERSITY IN the presence of different ethnic and religious groups in this one country. Jews are 75% of ISRAEL & PALESTINE Israel’s population, while Arabs are 20.7%, CULTURAL PROBLEMS and other groups are 4.3%. Because Jews are the majority, the main language is Hebrew. AROUND THE EARTH The country’s second official language is Arabic, mainly used by the Arab community in This pamphlet will explore global Israel. English is one of the main “universal sources of tension such as languages” and is used as a second language. About 15% of the population speaks Russian, language diversity in Israel and Israel is a Middle Eastern Country that spoken by immigrants from the Soviet Union. Palestine, the human footprint lies on the Mediterranean coast and has a One reason for the green color in the West level in Japan, and the number of population of about 8.38 million. Palestine has Bank and the Gaza Strip is the “1969 a population of about 4.22 million and includes women in parliament in Rwanda. Borders.” After the Israeli occupation and the the West Bank and the Gaza Strip on the 6-day war between the Arabs and the Israelis eastern Mediterranean coast. It is in the heart in 1967, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip of the Holy Land surrounded by Israel, Jordan, remained as Palestine and the home of the Egypt, Syria, and Lebanon. Arabs. HUMAN FOOTPRINT OF JAPAN According to the map, Israel is more linguistically diverse than most of its surrounding countries. -

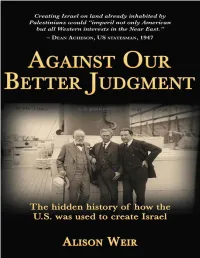

Against Our Better Judgment: the Hidden History of How the U.S. Was

Against Our Better Judgment The hidden history of how the U.S. was used to create Israel ALISON WEIR Copyright © 2014 Alison Weir All rights reserved. DEDICATION To Laila, Sarah, and Peter CONTENTS Aknowledgments Preface Chapter One: How the U.S. “Special Relationship” with Israel came about Chapter Two: The beginnings Chapter Three: Louis Brandeis, Zionism, and the “Parushim” Chapter Four: World War I & the Balfour Declaration Chapter Five: Paris Peace Conference 1919: Zionists defeat calls for self- determination Chapter Six: Forging an “ingathering” of all Jews Chapter Seven: The modern Israel Lobby is born Chapter Eight: Zionist Colonization Efforts in Palestine Chapter Nine: Truman Accedes to Pro-Israel Lobby Chapter Ten: Pro-Israel Pressure on General Assembly Members Chapter Eleven: Massacres and the Conquest of Palestine Chapter Twelve: U.S. front groups for Zionist militarism Chapter Thirteen: Infiltrating displaced person’s camps in Europe to funnel people to Palestine Chapter Fourteen: Palestinian refugees Chapter Fifteen: Zionist influence in the media Chapter Sixteen: Dorothy Thompson, played by Katharine Hepburn & Lauren Bacall Works Cited Further Reading Endnotes ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to Katy, who plowed through my piles of obscure books and beyond to check it; to Sarah, whose design so enhanced it; to Monica, whose splendid work kept things together; and to the special, encouraging friends (you know who you are) who have made this all possible. Above all, I am profoundly grateful to the authors and editors who have produced superb work on this issue for so many years, many receiving little personal gain despite the excellence and dedication of their labors. -

PURE AS the DRIVEN SNOW, OR HEARTS of DARKNESS? by Shay Fogelman Haaretz 18 Mars 2012

PURE AS THE DRIVEN SNOW, OR HEARTS OF DARKNESS? By Shay Fogelman Haaretz 18 mars 2012 Haaretz spent five days with the controversial 'Lev Tahor' Haredi community in Canada to uncover the truth about the sect and its charismatic head, Rabbi Shlomo Helbrans. Part one of a two-part series. Rabbi Shlomo Helbrans is trying to get me to repent and become religious. To this end, for the past four months he has been spending hours with me on the phone from Canada. He believes I have a good Jewish soul that somehow got lost, and insists he can, and must, show it the way back. I disagree with him about the soul, the Jewish thing and the path, but do find many other interesting subjects to discuss with him. Rabbi Helbrans is a bit disappointed that I haven’t become religious yet, but he’s not giving up. He keeps trying at every opportunity. He maintains that discussion of God should not be relegated to the realm of fate, but rather that it is an absolute and provable truth. Therefore, before he would consent to be interviewed, he insisted that I devote 10 hours to listening to him present his proofs. Helbrans declared that if I came to him with an honest desire to explore the truth, I would no longer be able to deny God and his Torah, as given to the Jewish people at Sinai. Despite my skepticism, I acceded to his demand. Because of this same skepticism, I also agreed to pledge to him that if I was in fact convinced, I would change my life and become religious. -

The Balfour Declaration Was More Than the Promise of One Nation » Mosaic

8/22/2018 The Balfour Declaration Was More than the Promise of One Nation » Mosaic THE BALFOUR DECLARATION WAS MORE THAN THE PROMISE OF ONE NATION https://mosaicmagazine.com/response/2017/06/the-balfour-declaration-was-more-than-the-promise-of- one-nation/ By affirming the right of any Jew to call Palestine home, it also changed the international status of the Jewish people. June 28, 2017 | Martin Kramer This is a response to The Forgotten Truth about the Balfour Declaration, originally published in Mosaic in June 2017 In 1930, the British Colonial Office published a “white paper” that Zionists saw as a retreat from the Balfour Declaration. David Lloyd George, whose government had issued the declaration in 1917, was long out of office and now in the twilight of his political career. In an indignant speech, he insisted that his own country had no authority to downgrade the declaration, because it Sara and Benjamin Netanyahu view the Balfour constituted a commitment made by all of Declaration at the British Library. Government the Allies in the Great War: Press Office Israel. In wartime we were anxious to secure the good will of the Jewish community throughout the world for the Allied cause. The Balfour Declaration was a gesture not merely on our part but on the part of the Allies to secure that valuable support. It was prepared after much consideration, not merely of its policy, but of its actual wording, by the representatives of all the Allied and associated countries including America, and of our dominion premiers. There was some exaggeration here; not all of the Allies shared the same understanding of the policy or saw the “actual wording.” But Lloyd George pointed to the forgotten truth that I sought to resurrect through my essay.