Faydra L. Shapiro Christian Zionism: Navigating the Jewish-Christian Border (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2015), Paperback, Xxiv + 167 Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Christian Zionist Lobby and U.S.-Israel Policy

University of South Florida Digital Commons @ University of South Florida Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 6-25-2010 The Christian Zionist Lobby and U.S.-Israel Policy Mark G. Grzegorzewski University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Grzegorzewski, Mark G., "The Christian Zionist Lobby and U.S.-Israel Policy" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd/3671 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Christian Zionist Lobby and U.S.-Israel Policy by Mark G. Grzegorzewski A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Government and International Affairs College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Mark Amen, Ph.D. Michael Solomon, Ph.D. Abdelwahab Hechiche, Ph.D. Date of Approval: June 25, 2010 Keywords: Israel, Road Map, Unilateralism, United States, Christian Zionists Copyright © 2010, Mark G. Grzegorzewski DEDICATION For my beautiful daughter, Riley Katelyn. Without the joy you bring to my life I never would have continued to pursue my academic goals. Your very being provides me with the inspiration to make the world a better place for you to grow up in. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like thank Dr. -

PHILOLOGIA ARTS & Vol

COLLEGE OF LIBERALPHILOLOGIA ARTS & Vol. X HUMAN SCIENCES Undergraduate Research Journal Associate Editor: Holly Hunter Faculty Reviewer: Shaily Patel Author: Rachel Sutphin Title: The Impact of Christianity on Israel-Palestine Peace Relations ABSTRACT When analyzing the Israel-Palestine conflict, one may be tempted to focus solely on the political and historical situation of the geographic land. However, it is also important to consider the deeply embedded religious traditions of the area. When doing so, one will come across Christian Zionism, an impediment to peace. Some of the most prominent voices find validation for their narratives and actions through Christian Zionism. Zionism, in all forms, is an ideology that anchors Jews to Eretz Yisrael, the land of Biblical Israel. Some forms of Zionism include a system of balancing accumulations of land, resources, and wealth with the displacement of Palestinians. This belief that the Jews have a divineVOL. right to the X accumulation of land and resources legitimizes Zionism in their conquering of the past-legitimate Palestine. Thus, as Palestinian scholar Edward Said states, Zionism is an imported ideology in which Palestinians “pay and suffer” (Said, 1978). Christian Zionism consists of a variety of beliefs that promote and protect the Israeli state and government, while also dehumanizing the Palestinians and equating anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism. As a result, Christian Zionism is a challenging obstacle, one that is necessary to overcome to establish peace. Therefore, due to Christians being called to live peacefully (Colossians 3:15), the Christian tradition must seek and adhere to an alternative theology to Christian Zionism. Palestinian Christian Liberation Theology is a relevant way to interpret Scriptures based on the Christian tradition of peace found in the Old and New Testaments. -

The Role of Ultra-Orthodox Political Parties in Israeli Democracy

Luke Howson University of Liverpool The Role of Ultra-Orthodox Political Parties in Israeli Democracy Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy By Luke Howson July 2014 Committee: Clive Jones, BA (Hons) MA, PhD Prof Jon Tonge, PhD 1 Luke Howson University of Liverpool © 2014 Luke Howson All Rights Reserved 2 Luke Howson University of Liverpool Abstract This thesis focuses on the role of ultra-orthodox party Shas within the Israeli state as a means to explore wider themes and divisions in Israeli society. Without underestimating the significance of security and conflict within the structure of the Israeli state, in this thesis the Arab–Jewish relationship is viewed as just one important cleavage within the Israeli state. Instead of focusing on this single cleavage, this thesis explores the complex structure of cleavages at the heart of the Israeli political system. It introduces the concept of a ‘cleavage pyramid’, whereby divisions are of different saliency to different groups. At the top of the pyramid is division between Arabs and Jews, but one rung down from this are the intra-Jewish divisions, be they religious, ethnic or political in nature. In the case of Shas, the religious and ethnic elements are the most salient. The secular–religious divide is a key fault line in Israel and one in which ultra-orthodox parties like Shas are at the forefront. They and their politically secular counterparts form a key division in Israel, and an exploration of Shas is an insightful means of exploring this division further, its history and causes, and how these groups interact politically. -

Global Jewish Forum Haredim and the Jewish Collective: Engaging with Voices from the Field

Global Jewish Forum Haredim and the Jewish Collective: Engaging with Voices from the Field Presented by Makom 27 th February, 2012 - 4 Adar I, 5772 For internal educational use only Printed at the Jewish Agency 1 Table of Contents The Back Story • What is Orthodoxy? Samuel C. Heilman and Menachem Friedman, The Haredim in Israel • Zionism and Judaism From The Jewish Political Tradition Volume 1 Authority (2000) • The “Status Quo” and David Ben Gurion From the Jewish Agency for Israel to Agudat Yisrael 19th June, 1947 • Israelis and Religion Professor Michael Rosenak, from The Land of Israel: Its contemporary meaning (1992) • A different approach Jeri Langer, from The Jew in the Modern World (1995) Statistics and Policies • Demographics …………………………………………………………………………………………. 5 • Education ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 • Army ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 • Work ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 7 Israel 5772 – so far • Risking one’s life on the bus ……………………………………………………………………… 10 • A civil war no one wants …………………………………………………………………………. 14 • Statement from Agudath Israel of America ……………………………………………….. 16 • Gender Trouble ………………………………………………………………………………………. 17 • Haredi leaders must speak out against zealots ………………………………………….. 20 • Lessons from Bet Shemesh ………………………………………………………………………. 22 • The remarkable good news about the Haredim …………………………………………. 26 2 Global Jewish Forum A biennial event for deep consideration of the pressing issues of the Jewish People… Moving beyond the communal headlines to examine the deep issues that drive them... International Jewish leaders deliberately not taking decisions, but together deciding to deliberate... Young committed adults sit around the table with institutional leaders, sharing perspectives and gaining understanding. Welcome to the 2 nd Global Jewish Forum. At the inaugural Forum last June the Makom team presented a day that explored the intra-communal challenges of the fight against delegitimation. -

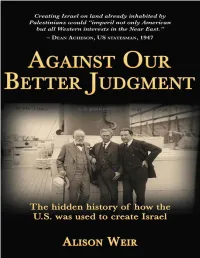

Against Our Better Judgment: the Hidden History of How the U.S. Was

Against Our Better Judgment The hidden history of how the U.S. was used to create Israel ALISON WEIR Copyright © 2014 Alison Weir All rights reserved. DEDICATION To Laila, Sarah, and Peter CONTENTS Aknowledgments Preface Chapter One: How the U.S. “Special Relationship” with Israel came about Chapter Two: The beginnings Chapter Three: Louis Brandeis, Zionism, and the “Parushim” Chapter Four: World War I & the Balfour Declaration Chapter Five: Paris Peace Conference 1919: Zionists defeat calls for self- determination Chapter Six: Forging an “ingathering” of all Jews Chapter Seven: The modern Israel Lobby is born Chapter Eight: Zionist Colonization Efforts in Palestine Chapter Nine: Truman Accedes to Pro-Israel Lobby Chapter Ten: Pro-Israel Pressure on General Assembly Members Chapter Eleven: Massacres and the Conquest of Palestine Chapter Twelve: U.S. front groups for Zionist militarism Chapter Thirteen: Infiltrating displaced person’s camps in Europe to funnel people to Palestine Chapter Fourteen: Palestinian refugees Chapter Fifteen: Zionist influence in the media Chapter Sixteen: Dorothy Thompson, played by Katharine Hepburn & Lauren Bacall Works Cited Further Reading Endnotes ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to Katy, who plowed through my piles of obscure books and beyond to check it; to Sarah, whose design so enhanced it; to Monica, whose splendid work kept things together; and to the special, encouraging friends (you know who you are) who have made this all possible. Above all, I am profoundly grateful to the authors and editors who have produced superb work on this issue for so many years, many receiving little personal gain despite the excellence and dedication of their labors. -

PURE AS the DRIVEN SNOW, OR HEARTS of DARKNESS? by Shay Fogelman Haaretz 18 Mars 2012

PURE AS THE DRIVEN SNOW, OR HEARTS OF DARKNESS? By Shay Fogelman Haaretz 18 mars 2012 Haaretz spent five days with the controversial 'Lev Tahor' Haredi community in Canada to uncover the truth about the sect and its charismatic head, Rabbi Shlomo Helbrans. Part one of a two-part series. Rabbi Shlomo Helbrans is trying to get me to repent and become religious. To this end, for the past four months he has been spending hours with me on the phone from Canada. He believes I have a good Jewish soul that somehow got lost, and insists he can, and must, show it the way back. I disagree with him about the soul, the Jewish thing and the path, but do find many other interesting subjects to discuss with him. Rabbi Helbrans is a bit disappointed that I haven’t become religious yet, but he’s not giving up. He keeps trying at every opportunity. He maintains that discussion of God should not be relegated to the realm of fate, but rather that it is an absolute and provable truth. Therefore, before he would consent to be interviewed, he insisted that I devote 10 hours to listening to him present his proofs. Helbrans declared that if I came to him with an honest desire to explore the truth, I would no longer be able to deny God and his Torah, as given to the Jewish people at Sinai. Despite my skepticism, I acceded to his demand. Because of this same skepticism, I also agreed to pledge to him that if I was in fact convinced, I would change my life and become religious. -

The Balfour Declaration Was More Than the Promise of One Nation » Mosaic

8/22/2018 The Balfour Declaration Was More than the Promise of One Nation » Mosaic THE BALFOUR DECLARATION WAS MORE THAN THE PROMISE OF ONE NATION https://mosaicmagazine.com/response/2017/06/the-balfour-declaration-was-more-than-the-promise-of- one-nation/ By affirming the right of any Jew to call Palestine home, it also changed the international status of the Jewish people. June 28, 2017 | Martin Kramer This is a response to The Forgotten Truth about the Balfour Declaration, originally published in Mosaic in June 2017 In 1930, the British Colonial Office published a “white paper” that Zionists saw as a retreat from the Balfour Declaration. David Lloyd George, whose government had issued the declaration in 1917, was long out of office and now in the twilight of his political career. In an indignant speech, he insisted that his own country had no authority to downgrade the declaration, because it Sara and Benjamin Netanyahu view the Balfour constituted a commitment made by all of Declaration at the British Library. Government the Allies in the Great War: Press Office Israel. In wartime we were anxious to secure the good will of the Jewish community throughout the world for the Allied cause. The Balfour Declaration was a gesture not merely on our part but on the part of the Allies to secure that valuable support. It was prepared after much consideration, not merely of its policy, but of its actual wording, by the representatives of all the Allied and associated countries including America, and of our dominion premiers. There was some exaggeration here; not all of the Allies shared the same understanding of the policy or saw the “actual wording.” But Lloyd George pointed to the forgotten truth that I sought to resurrect through my essay. -

Israel and Zionism in the Eyes of Palestinian Christian Theologians

religions Article Israel and Zionism in the Eyes of Palestinian Christian Theologians Giovanni Matteo Quer Kantor Center for the Study of Contemporary European Jewry, Tel-Aviv University, Tel Aviv-Yafo 69978, Israel; [email protected] Received: 31 May 2019; Accepted: 1 August 2019; Published: 19 August 2019 Abstract: Christian activism in the Arab–Israeli conflict and theological reflections on the Middle East have evolved around Palestinian liberation theology as a theological–political doctrine that scrutinizes Zionism, the existence of Israel and its policies, developing a biblical hermeneutics that reverses the biblical narrative, in order to portray Israel as a wicked regime that operates in the name of a fallacious primitive god and that uses false interpretations of the scriptures. This article analyzes the theological political–theological views applied to the Arab–Israeli conflict developed by Geries Khoury, Naim Ateek, and Mitri Raheb—three influential authors and activists in different Christians denominations. Besides opposing Zionism and providing arguments for the boycott of Israel, such conceptualizations go far beyond the conflict, providing theological grounds for the denial of Jewish statehood echoing old anti-Jewish accusations. Keywords: Palestine; Israel; Zionism; Christianity; antisemitism 1. Introduction The way Palestinian Christian communities relate to Israel is defined by nationality and religion. As Palestinians, Christians tend to embrace the national narrative that advances a political discourse opposed to Israel’s policies and, at times, also questions its right to exist as a Jewish state. As Christians, Palestinians struggle with religious conceptualizations of Judaism and Zionism that have developed in the Christian world ever since the Holocaust. -

American Christian Zionism and U.S. Policy on Settlements in the Palestinian Occupied Territories

Lauer American Christian Zionism and U.S. Policy on Settlements in the Palestinian Occupied Territories Erin Lauer American University School of International Service Honors in International Studies Senior Capstone Advisor: Boaz Atzili Spring 2009 - 1 - Lauer “If America forces Israel to give up the Golan Heights or the West Bank (Judea and Samaria), it will clearly violate scripture. We are giving the enemies of Israel the high ground in the coming war for Israel’s survival. It’s time for our national leaders in Washington to stop this madness.” Reverend John Hagee President, Christians United for Israel In Defense of Israel , 2007 - 2 - Lauer Foreword This research is the culmination of spending nearly 2 years living and working in different aspects of the Arab- Israeli conflict. Living with the Mhassan family, who fled from Ramallah to Amman, Jordan during the 1967 war, shaped my passion for the conflict, as I saw several aspects of the Palestinian Diaspora experience in my time abroad from September 2007-June 2008. The past academic year has been focused on the American political connection to the conflict, experienced through my time interning at the American Task Force on Palestine and the Foundation for Middle East Peace. These experiences have been critical to my development as a student and as a researcher, and I can say certainly that without these experiences, this research would not have happened. In the course of this research, I have received great help from people on all sides of this issue, and without them, this paper would not be the piece it is today. -

Dispensationalist Christian Zionism and the Shaping of US Policy Towards Israel-Palestine

The Armageddon Lobby: Dispensationalist Christian Zionism and the Shaping of US Policy Towards Israel-Palestine Rammy M. Haija Holy Land Studies: A Multidisciplinary Journal, Volume 5, Number 1, May 2006, pp. 75-95 (Article) Published by Edinburgh University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/199773 [ This content has been declared free to read by the pubisher during the COVID-19 pandemic. ] [HLS 5.1 (2006) 75–95] ISSN 1474-9475 THE ARMAGEDDON LOBBY: DISPENSATIONALIST CHRISTIAN ZIONISM AND THE SHAPING OF US POLICY TOWARDS ISRAEL-PALESTINE1 Rammy M. Haija Doctoral Candidate in Sociology Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Virginia Tech, 560 McBryde Hall - 0137 Blacksburg, VA 24060, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT This article investigates the history of contemporary Christian Zionism in the United States and the impact of this movement on US policy issues related to Israel-Palestine. Dispensationalist Christian Zionists, often described the ‘Armageddon lobby’, make up the largest voting bloc in the Republican Party and have become a mainstay in US politics. More recently, the Christian Zionist lobby has had a profoundly damaging impact on the Israeli-Palestinian ‘peace process’ as well as creating a conspiracy of silence regarding Israeli offensives in the occupied Palestinian territories. Though the ‘Armageddon lobby’ has been successful in its efforts as a pro-Israel lobby, its infl uence is in fact counterproductive to Israel because the lobby hinders the prospect of Israel living in peace because of their policy of deterring the progression of negotiations. 1. Introduction to Christian Zionism While the alliance between America’s Christian Zionists and the pro-Israel lobby has been in existence for decades now, more recently it has become critical to examine this dynamic relationship because of the current volatile state resulting from the current Palestinian Intifada (uprising). -

Picking Sides in the Arab-Israeli Conflict

PICKING SIDES IN THE ARAB-ISRAELI CONFLICT: THE INFLUENCE OF RELIGIOUS BELIEF ON FOREIGN POLICY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Robertson School of Government Regent University In partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts By Rachel Sarah Wills Virginia Beach, Virginia April 2012 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Government ___________________________ Rachel Sarah Wills May 2012 Spencer Meredith, Ph.D., Committee Chairman Date Philip Bom, Ph.D., Committee Member Date Joseph Kickasola, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ii Copyright 2012 Rachel Sarah Wills All Rights Reserved iii To Greg and Kate SDG iv The views expressed in this thesis are those of the student and do not necessarily express any official positions of Regent University. v CONTENTS ABSTRACT viii INTRODUCTION 1 LITERATURE REVIEW 4 CHAPTER ONE: DEFINING KEY TERMS 22 Religious Belief 22 Democracy 31 Foreign Policy 40 CHAPTER TWO: HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF THE CONFLICT 45 Early Jewish Immigration 47 World War I 49 World War II and the Holocaust 51 Establishment of the State of Israel and the First Arab-Israeli Conflict 53 The 1967 War 67 CHAPTER THREE: RELEVANT ACTORS – ISRAEL, THE EUROPEAN 77 UNION, AND THE UNITED STATES Required Criteria 77 Omitted Actors 83 vi Israel 88 The European Union 89 The United States 91 CHAPTER FOUR: RELIGIOUS INFLUENCES 94 Israel 94 The European Union 100 The United States 106 CHAPTER FIVE: PAST POLICY POSITIONS 115 The Creation of the State of Israel: 1947-1948 115 The 1967 and 1973 Conflicts 130 The 1978 and 1993 Peace Agreements 148 CHAPTER SIX: CONCLUSIONS 170 BIBLIOGRAPHY 179 VITA 193 vii ABSTRACT PICKING SIDES IN THE ARAB-ISRAELI CONFLICT: THE INFLUENCE OF RELIGIOUS BELIEF ON FOREIGN POLICY This thesis seeks to analyze the motives that correlate to nations’ choices to defend one side to the exclusion of the other side in the Arab-Israeli conflict. -

Christian Zionism and Islamic Eschatology John W. Swails III, Ph

Christian Zionism and Islamic Eschatology John W. Swails III, Ph.D. Christian Zionists are very aware that their stand for the tiny state of Israel is not universally admired. Christian Zionism is, of course, a movement comprised of individuals, more often than not from a Protestant background, who support the modern state of Israel spiritually, politically, and financially from a Biblically-based worldview. Unique to this worldview has been a recent surge over the past 10 or 15 years, a momentum that has activated Christians from being sideline viewers to take a more active and practical role is supporting the tiny state. With this newfound momentum however, Christian Zionists have found themselves opposed on a variety of fronts. Among those in disagreement with Christian Zionism are other Christians who ascribe to what is known as “Replacement Theology.” This is a doctrine that maintains that all the Biblical promises to Israel and the covenants of God with Israel have been negated because of Israel’s unbelief. Moreover, those promises and covenants have actually been transferred from the physical state and people of Israel to the Church, which is physical and spiritual body of Christ. Those holding the “replacement” view contend that the Biblical texts with these promises to physical Israel can no longer be taken literally. That means that anyone holding the “replacement” view has to accept or insert or assume that those blessings pronounced in Scripture on Israel have devolved upon the Church away from Israel. This interpretation means that supporting the modern state of Israel is, at best, irrelevant; and, at worst, a tragic misunderstanding of Scripture with catastrophic consequences in the Middle East.