Differential Resting-State Connectivity Patterns of the Right Anterior and Posterior Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortices (DLPFC) in Schizophrenia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward a Common Terminology for the Gyri and Sulci of the Human Cerebral Cortex Hans Ten Donkelaar, Nathalie Tzourio-Mazoyer, Jürgen Mai

Toward a Common Terminology for the Gyri and Sulci of the Human Cerebral Cortex Hans ten Donkelaar, Nathalie Tzourio-Mazoyer, Jürgen Mai To cite this version: Hans ten Donkelaar, Nathalie Tzourio-Mazoyer, Jürgen Mai. Toward a Common Terminology for the Gyri and Sulci of the Human Cerebral Cortex. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy, Frontiers, 2018, 12, pp.93. 10.3389/fnana.2018.00093. hal-01929541 HAL Id: hal-01929541 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01929541 Submitted on 21 Nov 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. REVIEW published: 19 November 2018 doi: 10.3389/fnana.2018.00093 Toward a Common Terminology for the Gyri and Sulci of the Human Cerebral Cortex Hans J. ten Donkelaar 1*†, Nathalie Tzourio-Mazoyer 2† and Jürgen K. Mai 3† 1 Department of Neurology, Donders Center for Medical Neuroscience, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, Netherlands, 2 IMN Institut des Maladies Neurodégénératives UMR 5293, Université de Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France, 3 Institute for Anatomy, Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany The gyri and sulci of the human brain were defined by pioneers such as Louis-Pierre Gratiolet and Alexander Ecker, and extensified by, among others, Dejerine (1895) and von Economo and Koskinas (1925). -

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables: ROI Atlas Significant table grey matter Test ROI # Brainetome area beta volume EG pre vs post IT 8 'superior frontal gyrus, part 4 (dorsolateral area 6), right', 0.773 17388 11 'superior frontal gyrus, part 6 (medial area 9), left', 0.793 18630 12 'superior frontal gyrus, part 6 (medial area 9), right', 0.806 24543 17 'middle frontal gyrus, part 2 (inferior frontal junction), left', 0.819 22140 35 'inferior frontal gyrus, part 4 (rostral area 45), left', 1.3 10665 67 'paracentral lobule, part 2 (area 4 lower limb), left', 0.86 13662 EG pre vs post ET 20 'middle frontal gyrus, part 3 (area 46), right', 0.934 28188 21 'middle frontal gyrus, part 4 (ventral area 9/46 ), left' 0.812 27864 31 'inferior frontal gyrus, part 2 (inferior frontal sulcus), left', 0.864 11124 35 'inferior frontal gyrus, part 4 (rostral area 45), left', 1 10665 50 'orbital gyrus, part 5 (area 13), right', -1.7 22626 67 'paracentral lobule, part 2 (area 4 lower limb), left', 1.1 13662 180 'cingulate gyrus, part 3 (pregenual area 32), right', 0.9 10665 261 'Cerebellar lobule VIIb, vermis', -1.5 729 IG pre vs post IT 16 middle frontal gyrus, part 1 (dorsal area 9/46), right', -0.8 27567 24 'middle frontal gyrus, part 5 (ventrolateral area 8), right', -0.8 22437 40 'inferior frontal gyrus, part 6 (ventral area 44), right', -0.9 8262 54 'precentral gyrus, part 1 (area 4 head and face), right', -0.9 14175 64 'precentral gyrus, part 2 (caudal dorsolateral area 6), left', -1.3 18819 81 'middle temporal gyrus, part 1 (caudal area 21), left', -1.4 14472 -

A Comparison of Preoperative Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation and Intraoperative Direct Cortex Stimulation

CLINICAL ARTICLE J Neurosurg 134:1409–1418, 2021 Incidence and linguistic quality of speech errors: a comparison of preoperative transcranial magnetic stimulation and intraoperative direct cortex stimulation Ina Bährend, MD,1 Max R. Muench,1 Heike Schneider,1 Rabih Moshourab, MD,2 Felix R. Dreyer, MD,3 Peter Vajkoczy, MD,1 Thomas Picht, MD,1 and Katharina Faust, MD1 Departments of 1Neurosurgery and 2Anesthesiology, Charité, Universitätsmedizin Berlin; and 3Brain Language Laboratory, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany OBJECTIVE Given the interindividual variance of functional language anatomy, risk prediction based merely on ana- tomical data is insufficient in language area–related brain tumor surgery, suggesting the need for direct cortical and subcortical mapping during awake surgery. Reliable, noninvasive preoperative methods of language localization hold the potential for reducing the necessity for awake procedures and may improve patient counseling and surgical planning. Repetitive navigated transcranial magnetic stimulation (rnTMS) is an evolving tool for localizing language-eloquent areas. The aim of this study was to investigate the reliability of rnTMS in locating cortical language sites. METHODS Twenty-five patients with brain tumors in speech-related areas were prospectively evaluated with preopera- tive rnTMS (5 Hz, train of five, average 105% resting motor threshold) and navigated direct cortical stimulation (DCS; bipolar, 50 Hz, 6–8 mA, 200-μsec pulse width) during awake surgeries employing a picture-naming task. Positive and negative stimulation spots within the craniotomy were documented in the same MRI data set. TMS and DCS language- positive areas were compared with regard to their spatial overlap, their allocation in a cortical parcellation system, and their linguistic qualities. -

Seed MNI Coordinates Lobe

MNI Coordinates Seed Lobe (Hemisphere) Region BAa X Y Z FP1 -18 62 0 Frontal Lobe (L) Medial Frontal Gyrus 10 FPz 4 62 0 Frontal Lobe (R) Medial Frontal Gyrus 10 FP2 24 60 0 Frontal Lobe (R) Superior Frontal Gyrus 10 AF7 -38 50 0 Frontal Lobe (L) Middle Frontal Gyrus 10 AF3 -30 50 24 Frontal Lobe (L) Superior Frontal Gyrus 9 AFz 4 58 30 Frontal Lobe (R) Medial Frontal Gyrus 9 AF4 36 48 20 Frontal Lobe (R) Middle Frontal Gyrus 10 AF8 42 46 -4 Frontal Lobe (R) Inferior Frontal Gyrus 10 F7 -48 26 -4 Frontal Lobe (L) Inferior Frontal Gyrus 47 F5 -48 28 18 Frontal Lobe (L) Inferior Frontal Gyrus 45 F3 -38 28 38 Frontal Lobe (L) Precentral Gyrus 9 F1 -20 30 50 Frontal Lobe (L) Superior Frontal Gyrus 8 Fz 2 32 54 Frontal Lobe (L) Superior Frontal Gyrus 8 F2 26 32 48 Frontal Lobe (R) Superior Frontal Gyrus 8 F4 42 30 34 Frontal Lobe (R) Precentral Gyrus 9 F6 50 28 14 Frontal Lobe (R) Middle Frontal Gyrus 46 F8 48 24 -8 Frontal Lobe (R) Inferior Frontal Gyrus 47 FT9 -50 -6 -36 Temporal Lobe (L) Inferior Temporal Gyrus 20 FT7 -54 2 -8 Temporal Lobe (L) Superior Temporal Gyrus 22 FC5 -56 4 22 Frontal Lobe (L) Precentral Gyrus 6 FC3 -44 6 48 Frontal Lobe (L) Middle Frontal Gyrus 6 FC1 -22 6 64 Frontal Lobe (L) Middle Frontal Gyrus 6 FCz 4 6 66 Frontal Lobe (R) Medial Frontal Gyrus 6 FC2 28 8 60 Frontal Lobe (R) Sub-Gyral 6 FC4 48 8 42 Frontal Lobe (R) Middle Frontal Gyrus 6 FC6 58 6 16 Frontal Lobe (R) Inferior Frontal Gyrus 44 FT8 54 2 -12 Temporal Lobe (R) Superior Temporal Gyrus 38 FT10 50 -6 -38 Temporal Lobe (R) Inferior Temporal Gyrus 20 T7/T3 -

Cortical Parcellation Protocol

CORTICAL PARCELLATION PROTOCOL APRIL 5, 2010 © 2010 NEUROMORPHOMETRICS, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PRINCIPAL AUTHORS: Jason Tourville, Ph.D. Research Assistant Professor Department of Cognitive and Neural Systems Boston University Ruth Carper, Ph.D. Assistant Research Scientist Center for Human Development University of California, San Diego Georges Salamon, M.D. Research Dept., Radiology David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA WITH CONTRIBUTIONS FROM MANY OTHERS Neuromorphometrics, Inc. 22 Westminster Street Somerville MA, 02144-1630 Phone/Fax (617) 776-7844 neuromorphometrics.com OVERVIEW The cerebral cortex is divided into 49 macro-anatomically defined regions in each hemisphere that are of broad interest to the neuroimaging community. Region of interest (ROI) boundary definitions were derived from a number of cortical labeling methods currently in use. Protocols from the Laboratory of Neuroimaging at UCLA (LONI; Shattuck et al., 2008), the University of Iowa Mental Health Clinical Research Center (IOWA; Crespo-Facorro et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2000), the Center for Morphometric Analysis at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH-CMA; Caviness et al., 1996), a collaboration between the Freesurfer group at MGH and Boston University School of Medicine (MGH-Desikan; Desikan et al., 2006), and UC San Diego (Carper & Courchesne, 2000; Carper & Courchesne, 2005; Carper et al., 2002) are specifically referenced in the protocol below. Methods developed at Boston University (Tourville & Guenther, 2003), Brigham and Women’s Hospital (McCarley & Shenton, 2008), Stanford (Allan Reiss lab), the University of Maryland (Buchanan et al., 2004), and the University of Toyoma (Zhou et al., 2007) were also consulted. The development of the protocol was also guided by the Ono, Kubik, and Abernathy (1990), Duvernoy (1999), and Mai, Paxinos, and Voss (Mai et al., 2008) neuroanatomical atlases. -

Asymmetry, Connectivity, and Segmentation of the Arcuate Fascicle in the Human Brain

Brain Struct Funct DOI 10.1007/s00429-014-0751-7 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Asymmetry, connectivity, and segmentation of the arcuate fascicle in the human brain Juan C. Ferna´ndez-Miranda • Yibao Wang • Sudhir Pathak • Lucia Stefaneau • Timothy Verstynen • Fang-Cheng Yeh Received: 2 September 2013 / Accepted: 4 March 2014 Ó Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014 Abstract The structure and function of the arcuate fas- in the left arcuate, but not in the right one. The left arcuate cicle is still controversial. The goal of this study was to fascicle is formed by an inner or ventral pathway, which investigate the asymmetry, connectivity, and segmentation interconnects pars opercularis with superior and rostral patterns of the arcuate fascicle. We employed diffusion middle temporal gyri; and an outer or dorsal pathway, spectrum imaging reconstructed by generalized q-sampling which interconnects ventral precentral and caudal middle and we applied both a subject-specific approach (10 sub- frontal gyri with caudal middle and inferior temporal gyri. jects) and a template approach (q-space diffeomorphic The fiber microdissection results provided further support reconstruction of 30 subjects). We complemented our to our tractography studies. We propose the existence of imaging investigation with fiber microdissection of five primary and supplementary language pathways within the post-mortem human brains. Our results confirmed the dominant arcuate fascicle with potentially distinct func- highly leftward asymmetry of the arcuate fascicle. In the tional and lesional features. template, the left arcuate had a volume twice as large as the right one, and the left superior temporal gyrus provided Keywords Arcuate fascicle Á Diffusion spectrum five times more volume of fibers than its counterpart. -

Normal Cortical Anatomy

Normal Cortical Anatomy MGH Massachusetts General Hospital Harvard Medical School NORMAL CORTICAL ANATOMY • Sagittal • Axial • Coronal • The Central Sulcus NP/MGH Sagittal Neuroanatomy NP/MGH Cingulate sulcus Superior frontal gyrus Marginal ramus of Cingulate sulcus Cingulate gyrus Paracentral lobule Superior parietal lobule Parietooccipital sulcus Cuneus Calcarine sulcus Lingual gyrus Subcallosal gyrus Gyrus rectus Fastigium, fourth ventricle NP/MGH Superior frontal gyrus Cingulate sulcus Precentral gyrus Marginal ramus of Cingulate gyrus Central sulcus Cingulate sulcus Superior parietal lobule Precuneus Parietooccipital sulcus Cuneus Calcarine sulcus Frontomarginal gyrus Lingual gyrus Caudothallamic groove Gyrus rectus NP/MGH Precentral sulcus Central sulcus Superior frontal gyrus Marginal ramus of Corona radiata Cingulate sulcus Superior parietal lobule Precuneus Parietooccipital sulcus Calcarine sulcus Inferior occipital gyrus Lingual gyrus NP/MGH Central sulcus Superior parietal lobule Parietooccipital sulcus Frontopolar gyrus Frontomarginal gyrus Superior occipital gyrus Middle occipital gyrus Medial orbital gyrus Lingual gyrus Posterior orbital gyrus Inferior occipital gyrus Inferior temporal gyrus Temporal horn, lateral ventricle NP/MGH Central sulcus Superior Temporal gyrus Middle Temporal gyrus Inferior Temporal gyrus NP/MGH Central sulcus Superior parietal gyrus Inferior frontal gyrus Frontomarginal gyrus Anterior orbital gyrus Superior occipital gyrus Middle occipital Posterior orbital gyrus gyrus Superior Temporal gyrus Inferior -

Core-Example1.Pdf

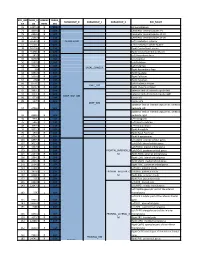

ROI_IND NUM_V HEMISP TISSUE_ SUBGROUP_0 SUBGROUP_1 SUBGROUP_2 ROI_NAME EX OX HERE SEG 95 12871.8 B WM corpus callosum 71 4899.8 B GM Cerebellar Vermal Lobules I-V 73 2858.8 B GM Cerebellar Vermal Lobules VIII-X 72 2266.9 B GM Cerebellar Vermal Lobules VI-VII 39 54582.6 L GM CEREBELLUM Left Cerebellum Exterior 41 15500.7 L WM Left Cerebellum White Matter 38 54379.4 R GM Right Cerebellum Exterior 40 15458.7 R WM Right Cerebellum White Matter 30 585.9 L GM Left Accumbens Area 37 3578.9 L GM Left Caudate 56 1597.6 L GM Left Pallidum 58 4942.3 L GM Left Putamen BASAL_GANGLIA 23 526 R GM Right Accumbens Area 36 3651.5 R GM Right Caudate 55 1638.8 R GM Right Pallidum 57 4726 R GM Right Putamen 60 8574.1 L GM Left Thalamus Proper DEEP_GM 59 8256.3 R GM Right Thalamus Proper 92 2887.7 L WM anterior limb of internal capsule left 91 3393.3 R WM anterior limb of internal capsule right DEEP_WM_GM 90 673.6 L WM fornix left 89 517.5 R WM fornix right DEEP_WM posterior limb of internal capsule inc. cerebral 94 2416.3 L WM peduncle left posterior limb of internal capsule inc. cerebral 93 2480.5 R WM peduncle right 32 993.7 L GM Left Amygdala 75 586.5 L GM Left Basal Forebrain 48 3597.7 L GM Left Hippocampus 31 1021.3 R GM Right Amygdala 76 593.1 R GM Right Basal Forebrain 47 3704.7 R GM Right Hippocampus 105 1897.7 L GM Left AOrG anterior orbital gyrus 137 3015.9 L GM Left LOrG lateral orbital gyrus 147 4637.3 L GM Left MOrG medial orbital gyrus 179 2915.7 L GM FRONTAL_INFERIOR_G Left POrG posterior orbital gyrus 104 2244.9 R GM M Right AOrG anterior orbital -

Cognitive Fatigue Is Associated with Altered Functional Connectivity in Interoceptive and Reward Pathways in Multiple Sclerosis

diagnostics Article Cognitive Fatigue Is Associated with Altered Functional Connectivity in Interoceptive and Reward Pathways in Multiple Sclerosis Michelle H. Chen 1,2, John DeLuca 1,2 , Helen M. Genova 1,2, Bing Yao 1,2 and Glenn R. Wylie 1,2,* 1 Kessler Foundation, East Hanover, NJ 07936, USA; [email protected] (M.H.C.); [email protected] (J.D.); [email protected] (H.M.G.); [email protected] (B.Y.) 2 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, New Jersey Medical School, Rutgers University, Newark, NJ 07103, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 24 September 2020; Accepted: 6 November 2020; Published: 10 November 2020 Abstract: Cognitive fatigue is common and debilitating among persons with multiple sclerosis (pwMS). Neural mechanisms underlying fatigue are not well understood, which results in lack of adequate treatment. The current study examined cognitive fatigue-related functional connectivity among 26 pwMS and 14 demographically matched healthy controls (HCs). Participants underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanning while performing a working memory task (n-back), with two conditions: one with higher cognitive load (2-back) to induce fatigue and one with lower cognitive load (0-back) as a control condition. Task-independent residual functional connectivity was assessed, with seeds in brain regions previously implicated in cognitive fatigue (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), insula, and striatum). Cognitive fatigue was measured using the Visual Analogue Scale of Fatigue (VAS-F). Results indicated that as VAS-F scores increased, HCs showed increased residual functional connectivity between the striatum and the vmPFC (crucial in reward processing) during the 2-back condition compared to the 0-back condition. -

Research Article Effective Connectivity Study Guiding the Neuromodulation Intervention in Figurative Language Comprehension Using Optical Neuroimaging

Hindawi Neural Plasticity Volume 2020, Article ID 8882207, 12 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8882207 Research Article Effective Connectivity Study Guiding the Neuromodulation Intervention in Figurative Language Comprehension Using Optical Neuroimaging Tania Alexandra Couto ,1,2 Shiyang Xu,1,2 Paulo Armada da Silva ,3 Chenggang Wu ,1,4,5 Karl Neergaard ,1 Meng-Yun Wang,1,2 Juan Zhang,1,3 Yutao Xiang,1,3 and Zhen Yuan 1,2 1Centre for Cognitive and Brain Sciences, University of Macau, Macau S.A.R., China 2Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau, Macau S.A.R.., China 3Faculty of Human Kinetics, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal 4Faculty of Education, University of Macau, Macau S.A.R., China 5School of Education, Shanghai International Studies University, Shanghai, China Correspondence should be addressed to Zhen Yuan; [email protected] Received 29 April 2020; Revised 14 August 2020; Accepted 11 September 2020; Published 6 October 2020 Academic Editor: Sergio Bagnato Copyright © 2020 Tania Alexandra Couto et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The current study is aimed at establishing links between brain network examination and neural plasticity studies measured by optical neuroimaging. Sixteen healthy subjects were recruited from the University of Macau to test the Granger Prediction Estimation (GPE) method to investigate brain network connectivity -

Dynamic Mapping of Human Cortical Development During Childhood Through Early Adulthood

Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood Nitin Gogtay*†, Jay N. Giedd*, Leslie Lusk*, Kiralee M. Hayashi‡, Deanna Greenstein*, A. Catherine Vaituzis*, Tom F. Nugent III*, David H. Herman*, Liv S. Clasen*, Arthur W. Toga‡, Judith L. Rapoport*, and Paul M. Thompson‡ *Child Psychiatry Branch, National Institutes of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892; and ‡Laboratory of Neuro Imaging, Department of Neurology, University of California School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1769 Communicated by Leslie G. Ungerleider, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, April 15, 2004 (received for review January 7, 2004) We report the dynamic anatomical sequence of human cortical temporal cortex, which contains association areas that integrate gray matter development between the age of 4–21 years using information from several sensory modalities, matured last. Fur- quantitative four-dimensional maps and time-lapse sequences. thermore, the maturation of the cortex also appeared to follow Thirteen healthy children for whom anatomic brain MRI scans were the evolutionary sequence in which these regions were created. obtained every 2 years, for 8–10 years, were studied. By using models of the cortical surface and sulcal landmarks and a statistical Methods model for gray matter density, human cortical development could Subjects. Sample demographics are shown in Table 1. All subjects be visualized across the age range in a spatiotemporally detailed were recruited from the community for an ongoing National time-lapse sequence. The resulting time-lapse ‘‘movies’’ reveal that Institute of Mental Health study of human brain development (i) higher-order association cortices mature only after lower-order (20). -

Primary Functional Brain Connections Associated with Melancholic Major

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Primary functional brain connections associated with melancholic major depressive disorder and modulation by antidepressants Naho Ichikawa1, Giuseppe Lisi2, Noriaki Yahata3, Go Okada1, Masahiro Takamura1, Ryu-ichiro Hashimoto4, Takashi Yamada2, Makiko Yamada3,5, Tetsuya Suhara3, Sho Moriguchi6, Masaru Mimura6, Yujiro Yoshihara7, Hidehiko Takahashi7,8, Kiyoto Kasai9, Nobumasa Kato4, Shigeto Yamawaki1, Ben Seymour2,10*, Mitsuo Kawato2, Jun Morimoto2 & Yasumasa Okamoto1* The limited efcacy of available antidepressant therapies may be due to how they afect the underlying brain network. The purpose of this study was to develop a melancholic MDD biomarker to identify critically important functional connections (FCs), and explore their association to treatments. Resting state fMRI data of 130 individuals (65 melancholic major depressive disorder (MDD) patients, 65 healthy controls) were included to build a melancholic MDD classifer, and 10 FCs were selected by our sparse machine learning algorithm. This biomarker generalized to a drug-free independent cohort of melancholic MDD, and did not generalize to other MDD subtypes or other psychiatric disorders. Moreover, we found that antidepressants had a heterogeneous efect on the identifed FCs of 25 melancholic MDDs. In particular, it did impact the FC between left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC)/inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC)/precuneus, ranked as the second ‘most important’ FC based on the biomarker weights, whilst other eight FCs were normalized. Given that left DLPFC has been proposed as an explicit target of depression treatments, this suggest that the limited efcacy of antidepressants might be compensated by combining therapies with targeted treatment as an optimized approach in the future.