United States Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Cheers for Judicial Restraint: Justice White and the Role of the Supreme Court Justice White and the Exercise of Judicial Power

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2003 Two Cheers for Judicial Restraint: Justice White and the Role of the Supreme Court Justice White and the Exercise of Judicial Power Dennis J. Hutchinson Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dennis J. Hutchinson, "Two Cheers for Judicial Restraint: Justice White and the Role of the Supreme Court Justice White and the Exercise of Judicial Power," 74 University of Colorado Law Review 1409 (2003). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWO CHEERS FOR JUDICIAL RESTRAINT: JUSTICE WHITE AND THE ROLE OF THE SUPREME COURT DENNIS J. HUTCHINSON* The death of a Supreme Court Justice prompts an account- ing of his legacy. Although Byron R. White was both widely admired and deeply reviled during his thirty-one-year career on the Supreme Court of the United States, his death almost a year ago inspired a remarkable reconciliation among many of his critics, and many sounded an identical theme: Justice White was a model of judicial restraint-the judge who knew his place in the constitutional scheme of things, a jurist who fa- cilitated, and was reluctant to override, the policy judgments made by democratically accountable branches of government. The editorial page of the Washington Post, a frequent critic during his lifetime, made peace post-mortem and celebrated his vision of judicial restraint.' Stuart Taylor, another frequent critic, celebrated White as the "last true believer in judicial re- straint."2 Judge David M. -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

Edward Douglas White: Frame for a Portrait Paul R

Louisiana Law Review Volume 43 | Number 4 Symposium: Maritime Personal Injury March 1983 Edward Douglas White: Frame for a Portrait Paul R. Baier Louisiana State University Law Center Repository Citation Paul R. Baier, Edward Douglas White: Frame for a Portrait, 43 La. L. Rev. (1983) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol43/iss4/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. V ( TI DEDICATION OF PORTRAIT EDWARD DOUGLASS WHITE: FRAME FOR A PORTRAIT* Oration at the unveiling of the Rosenthal portrait of E. D. White, before the Louisiana Supreme Court, October 29, 1982. Paul R. Baier** Royal Street fluttered with flags, we are told, when they unveiled the statue of Edward Douglass White, in the heart of old New Orleans, in 1926. Confederate Veterans, still wearing the gray of '61, stood about the scaffolding. Above them rose Mr. Baker's great bronze statue of E. D. White, heroic in size, draped in the national flag. Somewhere in the crowd a band played old Southern airs, soft and sweet in the April sunshine. It was an impressive occasion, reported The Times-Picayune1 notable because so many venerable men and women had gathered to pay tribute to a man whose career brings honor to Louisiana and to the nation. Fifty years separate us from that occasion, sixty from White's death. -

Supreme Court Database Code Book Brick 2018 02

The Supreme Court Database Codebook Supreme Court Database Code Book brick_2018_02 CONTRIBUTORS Harold Spaeth Michigan State University College of Law Lee Epstein Washington University in Saint Louis Ted Ruger University of Pennsylvania School of Law Sarah C. Benesh University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee Department of Political Science Jeffrey Segal Stony Brook University Department of Political Science Andrew D. Martin University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts Document Crafted On October 17, 2018 @ 11:53 1 of 128 10/17/18, 11:58 AM The Supreme Court Database Codebook Table of Contents INTRODUCTORY 1 Introduction 2 Citing to the SCDB IDENTIFICATION VARIABLES 3 SCDB Case ID 4 SCDB Docket ID 5 SCDB Issues ID 6 SCDB Vote ID 7 U.S. Reporter Citation 8 Supreme Court Citation 9 Lawyers Edition Citation 10 LEXIS Citation 11 Docket Number BACKGROUND VARIABLES 12 Case Name 13 Petitioner 14 Petitioner State 15 Respondent 16 Respondent State 17 Manner in which the Court takes Jurisdiction 18 Administrative Action Preceeding Litigation 19 Administrative Action Preceeding Litigation State 20 Three-Judge District Court 21 Origin of Case 22 Origin of Case State 23 Source of Case 24 Source of Case State 2 of 128 10/17/18, 11:58 AM The Supreme Court Database Codebook 25 Lower Court Disagreement 26 Reason for Granting Cert 27 Lower Court Disposition 28 Lower Court Disposition Direction CHRONOLOGICAL VARIABLES 29 Date of Decision 30 Term of Court 31 Natural Court 32 Chief Justice 33 Date of Oral Argument 34 Date of Reargument SUBSTANTIVE -

Cwa News-Fall 2016

2 Communications Workers of America / fall 2016 Hardworking Americans Deserve LABOR DAY: the Truth about Donald Trump CWA t may be hard ers on Trump’s Doral Miami project in Florida who There’s no question that Donald Trump would be to believe that weren’t paid; dishwashers at a Trump resort in Palm a disaster as president. I Labor Day Beach, Fla. who were denied time-and-a half for marks the tradi- overtime hours; and wait staff, bartenders, and oth- If we: tional beginning of er hourly workers at Trump properties in California Want American employers to treat the “real” election and New York who didn’t receive tips customers u their employees well, we shouldn’t season, given how earmarked for them or were refused break time. vote for someone who stiffs workers. long we’ve already been talking about His record on working people’s right to have a union Want American wages to go up, By CWA President Chris Shelton u the presidential and bargain a fair contract is just as bad. Trump says we shouldn’t vote for someone who campaign. But there couldn’t be a higher-stakes he “100%” supports right-to-work, which weakens repeatedly violates minimum wage election for American workers than this year’s workers’ right to bargain a contract. Workers at his laws and says U.S. wages are too presidential election between Hillary Clinton and hotel in Vegas have been fired, threatened, and high. Donald Trump. have seen their benefits slashed. He tells voters he opposes the Trans-Pacific Partnership – a very bad Want jobs to stay in this country, u On Labor Day, a day that honors working people trade deal for working people – but still manufac- we shouldn’t vote for someone who and kicks off the final election sprint to November, tures his clothing and product lines in Bangladesh, manufactures products overseas. -

The Protection of Missouri Governors Has Come a Long Way Since 1881, When Governor Thomas Crittenden Kept a .44-Caliber Smith and Wesson Revolver in His Desk Drawer

GOVERNOR’S SECURITY DIVISION The protection of Missouri governors has come a long way since 1881, when Governor Thomas Crittenden kept a .44-caliber Smith and Wesson revolver in his desk drawer. He had offered a $5,000 reward for the arrest and delivery of Frank and Jesse James, and kept the weapon handy to guard against retaliation. In less than a year, Jesse James had been killed, and in October 1882, Frank James surrendered, handing his .44 Remington revolver to Governor Crittenden in the governor’s office. In 1939, eight years after the creation of the Missouri State Highway Patrol, several troopers were assigned to escort and chauffeur Governor Lloyd Stark, and provide security at the Governor’s Mansion for the first family following death threats by Kansas City mobsters. Governor Stark had joined federal authorities in efforts to topple political boss Tom Pendergast. Within a year, Pendergast and 100 of his followers were indicted. In early 1963, Colonel Hugh Waggoner called Trooper Richard D. Radford into his office one afternoon. He told Tpr. Radford to report to him at 8 a.m. the following morning in civilian clothes. At that time, he would accompany Tpr. Radford to the governor’s office. The trooper was introduced to Governor John Dalton and was assigned to full-time security following several threats. Since security for the governor was in its infancy, Tpr. Radford had to develop procedures as he went along. There was no formal protection training available at this time, and the only equipment consisted of a suit, concealed weapon, and an unmarked car. -

2021 Bicentennial Inauguration of Michael L. Parson 57Th Governor of the State of Missouri

Missouri Governor — Michael L. Parson Office of Communications 2021 Bicentennial Inauguration of Michael L. Parson 57th Governor of the State of Missouri On Monday, January 11, 2021, Governor Michael L. Parson will be sworn in as the 57th Governor of the State of Missouri at the 2021 Bicentennial Inauguration. Governor Michael L. Parson Governor Parson is a veteran who served six years in the United States Army. He served more than 22 years in law enforcement, including 12 years as the sheriff of Polk County. He also served in the Missouri House of Representatives from 2005-2011, in the Missouri Senate from 2011-2017, and as Lieutenant Governor from 2017-2018. Governor Parson and First Lady Teresa live in Bolivar. Together they have two children and six grandchildren. Governor Parson was raised on a farm in Hickory County and graduated from Wheatland High School in Wheatland, Missouri. He is a small business owner and a third generation farmer who currently owns and operates a cow and calf operation. Governor Parson has a passion for sports, agriculture, Christ, and people. Health and Safety Protocols State and local health officials have been consulted for guidance to protect attendees, participants, and staff on safely hosting this year’s inaugural celebration. All inauguration guests will go through a health and security screening prior to entry. Inaugural events will be socially distanced, masks will be available and encouraged, and hand sanitizer will be provided. Guests were highly encouraged to RSVP in advance of the event in order to ensure that seating can be modified to support social distancing standards. -

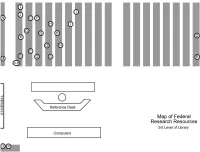

Fedresourcestutorial.Pdf

Guide to Federal Research Resources at Westminster Law Library (WLL) Revised 08/31/2011 A. United States Code – Level 3 KF62 2000.A2: The United States Code (USC) is the official compilation of federal statutes published by the Government Printing Office. It is arranged by subject into fifty chapters, or titles. The USC is republished every six years and includes yearly updates (separately bound supplements). It is the preferred resource for citing statutes in court documents and law review articles. Each statute entry is followed by its legislative history, including when it was enacted and amended. In addition to the tables of contents and chapters at the front of each volume, use the General Indexes and the Tables volumes that follow Title 50 to locate statutes on a particular topic. Relevant libguide: Federal Statutes. • Click and review Publication of Federal Statutes, Finding Statutes, and Updating Statutory Research tabs. B. United States Code Annotated - Level 3 KF62.5 .W45: Like the USC, West’s United States Code Annotated (USCA) is a compilation of federal statutes. It also includes indexes and table volumes at the end of the set to assist navigation. The USCA is updated more frequently than the USC, with smaller, integrated supplement volumes and, most importantly, pocket parts at the back of each book. Always check the pocket part for updates. The USCA is useful for research because the annotations include historical notes and cross-references to cases, regulations, law reviews and other secondary sources. LexisNexis has a similar set of annotated statutes titled “United States Code Service” (USCS), which Westminster Law Library does not own in print. -

Katy Trail Connection Sample Letter

SAMPLE LETTER OF SUPPORT FOR KATY TRAIL CONNECTION TO KANSAS CITY Governor Matt Blunt Room 216, State Capitol Building Jefferson City MO 65101 Governor Blunt, The potential to "complete the Katy Trail" by connecting the trail to the Kansas City metropolitan area, creating a seamless trail connection across the entire state, is an exciting one for Missouri. The Kansas City connection will help maintain the Katy Trail's status as one of Missouri's most popular state parks and an international tourist and recreation destination. Connecting the Katy Trail to Kansas City will make the trail the centerpiece of a compete, seamless statewide trail network that will allow bicyclists, runners, walkers, hikers, nature enthusiasts, bird watchers, and others to safely connect to communities and natural areas across Missouri. The potential for the Katy Trail to act as the hub of a "Quad State Trail", connecting communities in Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, and Illinois to those in Missouri, creates additional potential for tourism and economic development. The connection between the existing Katy Trail and the Kansas City metropolitan area is the key to allowing this Quad State Trail system to develop. The complete Katy Trail and the Quad-State Trail System will provide tremendous tourism, economic development, and public health benefits to communities and to the public. I support the Katy Trail connection to Kansas City, commend its economic, natural, and health benefits, and respectfully urge the Governor, the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, the Missouri Attorney General, and other interested parties to move with all due haste in completing the Katy Trail network from state line to state line. -

ARIZONA STATE LEGISLATURE V. ARIZONA INDEPENDENT REDISTRICTING COMMISSION and the FUTURE of REDISTRICTING REFORM David Gartner*

ARIZONA STATE LEGISLATURE V. ARIZONA INDEPENDENT REDISTRICTING COMMISSION AND THE FUTURE OF REDISTRICTING REFORM David Gartner* INTRODUCTION In 2018, voters in five different states passed successful initiatives that made it harder for politicians to choose their own districts and easier for independent voices to shape the redistricting process.1 This unprecedented transformation in the redistricting process would not have happened without the Supreme Court’s decision in Arizona Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission.2 That decision confirmed the constitutionality of Arizona’s own Independent Redistricting Commission and created an outlet for citizens frustrated with dysfunctional governance and unresponsive legislators to initiate reforms through the initiative process. All of these 2018 initiatives created or expanded state redistricting commissions which are to some degree insulated from the direct sway of the majority party in their respective legislatures.3 The Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission has proven to be a model for some states and an inspiration for many more with respect to * Professor of Law at Arizona State University, Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law. 1. Brett Neely & Sean McMinn, Voters Rejected Gerrymandering in 2018, But Some Lawmakers Try to Hold Power, NRP (Dec. 28, 2018, 5:00 AM), https://www.npr.org/2018/12/28/675763553/voters-rejected-gerrymandering-in-2018-but-some- lawmakers-try-to-hold-power [https://perma.cc/3RJH-39P9] (noting voters in Ohio, Colorado, Michigan, Missouri, -

Missouri Attorney General Enforcement Actions

Journal of Environmental and Sustainability Law Missouri Environmental Law and Policy Review Volume 5 Article 7 Issue 3 1997 1997 Missouri Attorney General Enforcement Actions Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/jesl Part of the Environmental Law Commons Recommended Citation Missouri Attorney General Enforcement Actions , 5 Mo. Envtl. L. & Pol'y Rev. 185 (1997) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/jesl/vol5/iss3/7 This Missouri Attorney General Enforcement Action is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Environmental and Sustainability Law by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Attorney General Enforcement Actions action in April by the Missouri Department of Natural Resources. MISSOURI ATTORNEY GENERAL The lawsuit asks the court ENFORCEMENT ACTIONS to order the defendants to transport their wastewater to another permit- ted facility until a proper treatment facility can be installed at the restaurant. Nixon also wants the Napalm Train Denied Passage Nixon Sues Owners, Manager of defendants to be required to submit Through Missouri Pizza Hut in Shell Knob to Stop plans for a proper facility to the This Spring, a train carry- Pollution of Table Rock Lake MDNR for approval and then for ing 12,000 gallons of napalm On May 14, 1998, Mis- the defendants to construct and destined for an Indiana facility was souri Attorney General Jay Nixon operate that facility in compliance turned back from Missouri on its asked the Barry County Circuit with the law. -

Greitens Scandal Could Influence Missouri Special Election by Blake Nelson the Associated Press Published June 4, 2018

Greitens scandal could influence Missouri special election By Blake Nelson The Associated Press Published June 4, 2018 JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. — One of the first Republican legislators to publicly suggest impeaching former Missouri Gov. Eric Greitens will face a Democrat who tried to tie him to the scandal-plagued governor in a special election, just four days after Greitens resigned amid allegations of sexual misconduct and campaign violations. The election Tuesday to pick a replacement for former GOP state Sen. Ryan Silvey was already viewed as a potential political barometer for Missouri ahead of the midterms, but Greitens’ abrupt departure last week injects additional meaning into the race between two state representatives. Republican Kevin Corlew and Democrat Lauren Arthur both positioned themselves as Greitens critics long before his resignation, which happened as the Legislature considered impeachment. Corlew took a stronger stance against Greitens than most of his GOP colleagues when he released a statement in April saying that the House should “seriously consider impeachment.” However, a commercial from Arthur’s campaign says: “Jefferson City is corrupt, and politicians like Eric Greitens and Kevin Corlew are the problem.” The vacancy was triggered in January when Silvey was appointed to the Missouri Public Service Commission. Silvey, himself a frequent critic of Greitens, leaves behind a suburban Kansas City seat that provides both parties with some reason for optimism. In 2016, voters in Clay County, where it’s located, backed Republicans Greitens for governor and Donald Trump for president while picking Democrat Jason Kander for U.S. Senate. In 2012 they favored Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney while backing Democratic incumbents Claire McCaskill for Senate and Jay Nixon for governor.