The Supreme Court Database Codebook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Cheers for Judicial Restraint: Justice White and the Role of the Supreme Court Justice White and the Exercise of Judicial Power

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2003 Two Cheers for Judicial Restraint: Justice White and the Role of the Supreme Court Justice White and the Exercise of Judicial Power Dennis J. Hutchinson Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dennis J. Hutchinson, "Two Cheers for Judicial Restraint: Justice White and the Role of the Supreme Court Justice White and the Exercise of Judicial Power," 74 University of Colorado Law Review 1409 (2003). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWO CHEERS FOR JUDICIAL RESTRAINT: JUSTICE WHITE AND THE ROLE OF THE SUPREME COURT DENNIS J. HUTCHINSON* The death of a Supreme Court Justice prompts an account- ing of his legacy. Although Byron R. White was both widely admired and deeply reviled during his thirty-one-year career on the Supreme Court of the United States, his death almost a year ago inspired a remarkable reconciliation among many of his critics, and many sounded an identical theme: Justice White was a model of judicial restraint-the judge who knew his place in the constitutional scheme of things, a jurist who fa- cilitated, and was reluctant to override, the policy judgments made by democratically accountable branches of government. The editorial page of the Washington Post, a frequent critic during his lifetime, made peace post-mortem and celebrated his vision of judicial restraint.' Stuart Taylor, another frequent critic, celebrated White as the "last true believer in judicial re- straint."2 Judge David M. -

Constitutional Avoidance and the Roberts Court Neal Devins William & Mary Law School, [email protected]

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 2007 Constitutional Avoidance and the Roberts Court Neal Devins William & Mary Law School, [email protected] Repository Citation Devins, Neal, "Constitutional Avoidance and the Roberts Court" (2007). Faculty Publications. 346. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/346 Copyright c 2007 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs CONSTITUTIONAL A VOIDANCE AND THE ROBERTS COURT Neal Devins • This essay will extend Phil Frickey's argument about the Warren Court's constitutional avoidance to the Roberts Court. My concern is whether the conditions which supported constitutional avoidance by the Warren Court support constitutional avoidance by today's Court. For reasons I will soon detail, the Roberts Court faces a far different Congress than the Warren Court and, as such, need not make extensive use of constitutional avoidance. In Getting from Joe to Gene (McCarthy), Phil Frickey argues that the Warren Court avoided serious conflict with Congress in the late 1950s by exercising subconstitutional avoidance. 1 In other words, the Court sought to avoid congressional backlash by refraining from declaring statutes unconstitutional. Instead, the Court sought to invalidate statutes or congressional actions based on technicalities. If Congress disagreed with the results reached by the Court, lawmakers could have taken legislative action to remedy the problem. This practice allowed the Court to maintain an opening through which it could backtrack and decide similar cases differently without reversing a constitutional decision. In understanding the relevance of Frickey's argument to today's Court, it is useful to compare Court-Congress relations during the Warren Court of the late 1950s to those during the final years of the Rehnquist Court. -

The Warren Court and the Pursuit of Justice, 50 Wash

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 50 | Issue 1 Article 4 Winter 1-1-1993 The aW rren Court And The Pursuit Of Justice Morton J. Horwitz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Morton J. Horwitz, The Warren Court And The Pursuit Of Justice, 50 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 5 (1993), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol50/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE WARREN COURT AND THE PURSUIT OF JUSTICE MORTON J. HoRwiTz* From 1953, when Earl Warren became Chief Justice, to 1969, when Earl Warren stepped down as Chief Justice, a constitutional revolution occurred. Constitutional revolutions are rare in American history. Indeed, the only constitutional revolution prior to the Warren Court was the New Deal Revolution of 1937, which fundamentally altered the relationship between the federal government and the states and between the government and the economy. Prior to 1937, there had been great continuity in American constitutional history. The first sharp break occurred in 1937 with the New Deal Court. The second sharp break took place between 1953 and 1969 with the Warren Court. Whether we will experience a comparable turn after 1969 remains to be seen. -

The Importance of Dissent and the Imperative of Judicial Civility

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 28 Number 2 Symposium on Civility and Judicial Ethics in the 1990s: Professionalism in the pp.583-646 Practice of Law Symposium on Civility and Judicial Ethics in the 1990s: Professionalism in the Practice of Law The Importance of Dissent and the Imperative of Judicial Civility Edward McGlynn Gaffney Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Edward McGlynn Gaffney Jr., The Importance of Dissent and the Imperative of Judicial Civility, 28 Val. U. L. Rev. 583 (1994). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol28/iss2/5 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Gaffney: The Importance of Dissent and the Imperative of Judicial Civility THE IMPORTANCE OF DISSENT AND THE IMPERATIVE OF JUDICIAL CIVILITY EDWARD McGLYNN GAFFNEY, JR.* A dissent in a court of last resort is an appeal to the brooding spirit of the law, to the intelligence of a future day, when a later decision may possibly correct the errorinto which the dissentingjudge believes the court to have been betrayed... Independence does not mean cantankerousness and ajudge may be a strongjudge without being an impossibleperson. Nothing is more distressing on any bench than the exhibition of a captious, impatient, querulous spirit.' Charles Evans Hughes I. INTRODUCTION Charles Evans Hughes served as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court from 1910 to 1916 and as Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. -

Earl Warren: a Political Biography, by Leo Katcher; Warren: the Man, the Court, the Era, by John Weaver

Indiana Law Journal Volume 43 Issue 3 Article 14 Spring 1968 Earl Warren: A Political Biography, by Leo Katcher; Warren: The Man, The Court, The Era, by John Weaver William F. Swindler College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Judges Commons, and the Legal Biography Commons Recommended Citation Swindler, William F. (1968) "Earl Warren: A Political Biography, by Leo Katcher; Warren: The Man, The Court, The Era, by John Weaver," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 43 : Iss. 3 , Article 14. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol43/iss3/14 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEWS EARL WARREN: A POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY. By Leo Katcher. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967. Pp. i, 502. $8.50. WARREN: THEi MAN, THE COURT, THE ERA. By John D. Weaver. Boston: Little. Brown & Co., 1967. Pp. 406. $7.95. Anyone interested in collecting a bookshelf of serious reading on the various Chief Justices of the United States is struck at the outset by the relative paucity of materials available. Among the studies of the Chief Justices of the twentieth century there is King's Melville Weston, Fuller,' which, while not definitive, is reliable and adequate enough to have merited reprinting in the excellent paperback series being edited by Professor Philip Kurland of the University of Chicago. -

Edward Douglas White: Frame for a Portrait Paul R

Louisiana Law Review Volume 43 | Number 4 Symposium: Maritime Personal Injury March 1983 Edward Douglas White: Frame for a Portrait Paul R. Baier Louisiana State University Law Center Repository Citation Paul R. Baier, Edward Douglas White: Frame for a Portrait, 43 La. L. Rev. (1983) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol43/iss4/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. V ( TI DEDICATION OF PORTRAIT EDWARD DOUGLASS WHITE: FRAME FOR A PORTRAIT* Oration at the unveiling of the Rosenthal portrait of E. D. White, before the Louisiana Supreme Court, October 29, 1982. Paul R. Baier** Royal Street fluttered with flags, we are told, when they unveiled the statue of Edward Douglass White, in the heart of old New Orleans, in 1926. Confederate Veterans, still wearing the gray of '61, stood about the scaffolding. Above them rose Mr. Baker's great bronze statue of E. D. White, heroic in size, draped in the national flag. Somewhere in the crowd a band played old Southern airs, soft and sweet in the April sunshine. It was an impressive occasion, reported The Times-Picayune1 notable because so many venerable men and women had gathered to pay tribute to a man whose career brings honor to Louisiana and to the nation. Fifty years separate us from that occasion, sixty from White's death. -

The Sources and Consequences of Polarization in the U.S. Supreme Court

The Sources and Consequences of Polarization in the U.S. Supreme Court Brandon L. Bartels Associate Professor of Political Science George Washington University 2115 G St. NW, Suite 440 Washington, DC 20052 [email protected] Summary This chapter examines polarization in the U.S. Supreme Court, primarily from the post-New Deal era to the present. I describe and document how the ideological center on the Court has gradually shrunk over time, though importantly, it has not disappeared altogether. I provide an examination and discussion of both the sources and consequences of these trends. Key insights and findings include: Polarization in the Supreme Court has generally increased over time, though this trend has ebbed and flowed. The most robust center existed during the Burger Court of the mid to late 1970s, consisting of arguable five swing justices. Though the center has shrunk over time on the Court, it still exists due to (1) presidents from Truman to George H.W. Bush not placing exclusive emphasis on ideological compatibility and reliability when appointing justices; (2) an increase in the incidence of divided government; and (3) the rarity of strategic retirements by the justices. Since President Clinton took office, the norms have shifted more firmly to strategic retirements by the justices and presidents placing near exclusive emphasis on ideological compatibility and reliability in the appointment process. The existence of swing justices on the Court—even having just one swing justice—has kept Supreme Court outputs relatively moderate and stable despite Republican domination of appointments from Nixon to George H.W. Bush. The elimination of swing justices would likely lead to more volatile policy outputs that fluctuate based on membership changes. -

Supreme Court Database Code Book Brick 2018 02

The Supreme Court Database Codebook Supreme Court Database Code Book brick_2018_02 CONTRIBUTORS Harold Spaeth Michigan State University College of Law Lee Epstein Washington University in Saint Louis Ted Ruger University of Pennsylvania School of Law Sarah C. Benesh University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee Department of Political Science Jeffrey Segal Stony Brook University Department of Political Science Andrew D. Martin University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts Document Crafted On October 17, 2018 @ 11:53 1 of 128 10/17/18, 11:58 AM The Supreme Court Database Codebook Table of Contents INTRODUCTORY 1 Introduction 2 Citing to the SCDB IDENTIFICATION VARIABLES 3 SCDB Case ID 4 SCDB Docket ID 5 SCDB Issues ID 6 SCDB Vote ID 7 U.S. Reporter Citation 8 Supreme Court Citation 9 Lawyers Edition Citation 10 LEXIS Citation 11 Docket Number BACKGROUND VARIABLES 12 Case Name 13 Petitioner 14 Petitioner State 15 Respondent 16 Respondent State 17 Manner in which the Court takes Jurisdiction 18 Administrative Action Preceeding Litigation 19 Administrative Action Preceeding Litigation State 20 Three-Judge District Court 21 Origin of Case 22 Origin of Case State 23 Source of Case 24 Source of Case State 2 of 128 10/17/18, 11:58 AM The Supreme Court Database Codebook 25 Lower Court Disagreement 26 Reason for Granting Cert 27 Lower Court Disposition 28 Lower Court Disposition Direction CHRONOLOGICAL VARIABLES 29 Date of Decision 30 Term of Court 31 Natural Court 32 Chief Justice 33 Date of Oral Argument 34 Date of Reargument SUBSTANTIVE -

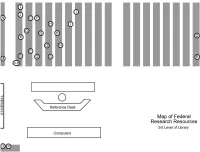

Fedresourcestutorial.Pdf

Guide to Federal Research Resources at Westminster Law Library (WLL) Revised 08/31/2011 A. United States Code – Level 3 KF62 2000.A2: The United States Code (USC) is the official compilation of federal statutes published by the Government Printing Office. It is arranged by subject into fifty chapters, or titles. The USC is republished every six years and includes yearly updates (separately bound supplements). It is the preferred resource for citing statutes in court documents and law review articles. Each statute entry is followed by its legislative history, including when it was enacted and amended. In addition to the tables of contents and chapters at the front of each volume, use the General Indexes and the Tables volumes that follow Title 50 to locate statutes on a particular topic. Relevant libguide: Federal Statutes. • Click and review Publication of Federal Statutes, Finding Statutes, and Updating Statutory Research tabs. B. United States Code Annotated - Level 3 KF62.5 .W45: Like the USC, West’s United States Code Annotated (USCA) is a compilation of federal statutes. It also includes indexes and table volumes at the end of the set to assist navigation. The USCA is updated more frequently than the USC, with smaller, integrated supplement volumes and, most importantly, pocket parts at the back of each book. Always check the pocket part for updates. The USCA is useful for research because the annotations include historical notes and cross-references to cases, regulations, law reviews and other secondary sources. LexisNexis has a similar set of annotated statutes titled “United States Code Service” (USCS), which Westminster Law Library does not own in print. -

"Slow Dance on the Killing Ground": the Willie Francis Case Revisited

DePaul Law Review Volume 32 Issue 1 Fall 1982 Article 2 "Slow Dance on the Killing Ground": The Willie Francis Case Revisited Arthur S. Miller Jeffrey H. Bowman Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Arthur S. Miller & Jeffrey H. Bowman, "Slow Dance on the Killing Ground": The Willie Francis Case Revisited, 32 DePaul L. Rev. 1 (1982) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol32/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "SLOW DANCE ON THE KILLING GROUND":t THE WILLIE FRANCIS CASE REVISITED tt Arthur S. Miller* and Jeffrey H. Bowman** The time is past in the history of the world when any living man or body of men can be set on a pedestal and decorated with a halo. FELIX FRANKFURTER*** The time is 1946. The place: rural Louisiana. A slim black teenager named Willie Francis was nervous. Understandably so. The State of Louisiana was getting ready to kill him by causing a current of electricity to pass through his shackled body. Strapped in a portable electric chair, a hood was placed over his head, and the electric chair attendant threw the switch, saying in a harsh voice "Goodbye, Willie." The chair didn't work properly; the port- able generator failed to provide enough voltage. Electricity passed through Willie's body, but not enough to kill him. -

Property and the Roberts Court

Property and the Roberts Court John G. Sprankling I. INTRODUCTION How do property owners fare before the Roberts Court? Quite well. Owners prevail in 86% of civil property-related disputes with government entities.1 But this statistic does not tell the whole story. This Article demonstrates that under the leadership of Chief Justice Roberts the Court has expanded the constitutional and statutory protections afforded to owners to a greater extent than any prior Court. It analyzes the key trends in the Court’s jurisprudence that will shape its decisions on property issues in future decades. Almost 100 years ago, Justice Holmes remarked that government regulation of property which went “too far” would be unconstitutional; yet the precise line between permissible and impermissible action has never been drawn.2 The issue has generated debate through much of American history, particularly in recent decades as the influence of conservative ideology on the Supreme Court has expanded. The Burger and Rehnquist Courts were broadly viewed as more sympathetic to private property than the Warren Court had been. However, the most controversial anti-owner decision of the modern era, Kelo v. City of New London,3 was decided in the final year of the Rehnquist Court. In Kelo, the Court held that the city was empowered to condemn owner-occupied homes and transfer them to private developers as part of an economic redevelopment project4―a ruling that ignited a firestorm of protest across the nation. In his confirmation hearings to serve as Chief Justice, John Roberts pledged to act as an “umpire” on the Court, a person with “no agenda” Distinguished Professor of Law, University of the Pacific, McGeorge School of Law. -

The Warren Court and Criminal Justice: a Quarter-Century Retrospective*

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 1995 The aW rren Court and Criminal Justice: A Quarter-Century Retrospective Yale Kamisar University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/276 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the Criminal Procedure Commons, Evidence Commons, Fourth Amendment Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Kamisar, Yale. "The aW rren Court and Criminal Justice: A Quarter-Century Retrospective." Tulsa L. J. 31, no. 1 (1995): 1-55. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TULSA LAW JOURNAL Volume 31 Fall 1995 Number 1 THE WARREN COURT AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE: A QUARTER-CENTURY RETROSPECTIVE* Yale Kamisart THE CLOSING YEARS OF THE WARREN COURT ERA ........... 3 THE RELEVANCE OF THE STRUGGLE FOR CIvIL RIGHTS ....... 6 CRITICISM OF MIRANDA - FROM OPPOSITE DIRECTIONS ...... 8 How DID MRANDA FARE IN THE POST-WARREN COURT ERA ? ................................................... 13 The Impeachment Cases ................................... 13 What is "Interrogation"Within the Meaning of Miranda?.. 14 The Edwards Case: A Victory for Miranda in the Post- Warren Court Era ....................................... 15 The Weaknesses in the Edwards Rule ...................... 17 What Does it Mean to Say That the Miranda Rules Are Merely "Prophylactic"? ................................. 19 Why the Initial Hostility to Miranda Has Dissipated ......