George Gershwin (B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edouard Lalo Symphonie Espagnole for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 21

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Edouard Lalo Born January 27, 1823, Lille, France. Died April 22, 1892, Paris, France. Symphonie espagnole for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 21 Lalo composed the Symphonie espagnole in 1874 for the violinist Pablo de Sarasate, who introduced the work in Paris on February 7, 1875. The score calls for solo violin and an orchestra consisting of two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, triangle, snare drum, harp, and strings. Performance time is approximately thirty-one minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lalo's Symphonie espagnole were given at the Auditorium Theatre on April 20 and 21, 1900, with Leopold Kramer as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Bizet's Carmen is often thought to have ignited the French fascination with all things Spanish, but Edouard Lalo got there first. His Symphonie espagnole—a Spanish symphony that's really more of a concerto—was premiered in Paris by the virtuoso Spanish violinist Pablo de Sarasate the month before Carmen opened at the Opéra-Comique. And although Carmen wasn't an immediate success (Bizet, who died shortly after the premiere, didn't live to see it achieve great popularity), the Symphonie espagnole quickly became an international hit. It's still Lalo's best-known piece by a wide margin, just as Carmeneventually became Bizet's signature work. Although the surname Lalo is of Spanish origin, Lalo came by his French first name (not to mention his middle names, Victoire Antoine) naturally. His family had been settled in Flanders and in northern France since the sixteenth century. -

Franco-Belgian Violin School: on the Rela- Tionship Between Violin Pedagogy and Compositional Practice Convegno Festival Paganiniano Di Carro 2012

5 il convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Convegno Società dei Concerti onlus 6 La Spezia Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini Lucca in collaborazione con Palazzetto Bru Zane Centre de Musique Romantique Française Venezia Musicalword.it CAMeC Centro Arte Moderna e Contemporanea Piazza Cesare Battisti 1 Comitato scientifico: Andrea Barizza, La Spezia Alexandre Dratwicki, Venezia Lorenzo Frassà, Lucca Roberto Illiano, Lucca / La Spezia Fulvia Morabito, Lucca Renato Ricco, Salerno Massimiliano Sala, Pistoia Renata Suchowiejko, Cracovia Convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Programma Lunedì 9 LUGLIO 10.00-10.30: Registrazione e accoglienza 10.30-11.00: Apertura dei lavori • Roberto Illiano (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini / Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Francesco Masinelli (Presidente Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Massimiliano Sala (Presidente Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca) • Étienne Jardin (Coordinatore scientifico Palazzetto Bru Zane, Venezia) • Cinzia Aloisini (Presidente Istituzione Servizi Culturali, Comune della Spezia) • Paola Sisti (Assessore alla Cultura, Provincia della Spezia) 10.30-11.30 Session 1 Nicolò Paganini e la scuola franco-belga presiede: Roberto Illiano 7 • Renato Ricco (Salerno): Virtuosismo e rivoluzione: Alexandre Boucher • Rohan H. Stewart-MacDonald (Leominster, UK): Approaches to the Orchestra in Paganini’s Violin Concertos • Danilo Prefumo (Milano): L’infuenza dei Concerti di Viotti, Rode e Kreutzer sui Con- certi per violino e orchestra di Nicolò Paganini -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

La Voix Humaine: a Technology Time Warp

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2016 La Voix humaine: A Technology Time Warp Whitney Myers University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.332 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Myers, Whitney, "La Voix humaine: A Technology Time Warp" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 70. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/70 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Sarasate.Pdf

2 SEMBLANZAS DE COMPOSITORES ESPAÑOLES 29 PABLO DE SARASATE 1844 -1908 Robin Stowell Catedrático de Música de la Universidad de Cardiff ablo de Sarasate fue un heredero espiritual de Nicolò Paganini, un artista elegante y do- tado para el espectáculo cuya facilidad y arte innatos y cuya aristocrática presencia es- P cénica lo convirtieron posiblemente en el más grande y más venerado violinista y com- positor español. Según los testimonios contemporáneos, su elegante pero sutil estilo interpre- tativo era único y su desenfadado virtuosismo difería radicalmente tanto del enfoque “clásico” y enormemente intelectual de la “escuela” rival alemana de Joseph Joachim y sus discípulos co- mo de la técnica más rigurosa y el sonido enérgico y vibrante del más joven Eugène Ysaÿe. Así, Sir George Henschel llegó hasta el extremo de señalar que la interpretación de Sarasate del Concierto para violín Op. 64 de Mendelssohn en el Festival del Bajo Rin de 1877 “fue pa- ra los oídos alemanes como una suerte de revelación, provocando un auténtico furor”. Sarasate introdujo distinción, encanto y refinamiento en el arte de la ejecución violinística y presentaba su música con magnetismo, una facilidad y elegancia naturales y ningún tipo de afectación, hasta el punto de que su público encontraba irresistible su estilo “acariciante”. Su timbre solía describirse como dulce y puro, aunque no especialmente fuerte o vibrante, pero go- zó de un especial renombre por la precisión de su interpretación, la justeza de su afinación y, en palabras de Sir Alexander Mackenzie, su “talento para penetrar de forma intuitiva ‘debajo En «Semblanzas de compositores españoles» un especialista en musicología expone el perfil biográfico y artístico de un autor relevante en la historia de la música en España y analiza el contexto musical, social y cultural en el que desarrolló su obra. -

Francis Poulenc and Surrealism

Wright State University CORE Scholar Master of Humanities Capstone Projects Master of Humanities Program 1-2-2019 Francis Poulenc and Surrealism Ginger Minneman Wright State University - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/humanities Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Repository Citation Minneman, G. (2019) Francis Poulenc and Surrealism. Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master of Humanities Program at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Humanities Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Minneman 1 Ginger Minneman Final Project Essay MA in Humanities candidate Francis Poulenc and Surrealism I. Introduction While it is true that surrealism was first and foremost a literary movement with strong ties to the world of art, and not usually applied to musicians, I believe the composer Francis Poulenc was so strongly influenced by this movement, that he could be considered a surrealist, in the same way that Debussy is regarded as an impressionist and Schönberg an expressionist; especially given that the artistic movement in the other two cases is a loose fit at best and does not apply to the entirety of their output. In this essay, which served as the basis for my lecture recital, I will examine some of the basic ideals of surrealism and show how Francis Poulenc embodies and embraces surrealist ideals in his persona, his music, his choice of texts and his compositional methods, or lack thereof. -

Heitor Villa-Lobos and the Parisian Art Scene: How to Become a Brazilian Musician*

1 Mana vol.1 no.se Rio de Janeiro Oct. 2006 Heitor Villa-Lobos and the Parisian art scene: how to become a Brazilian musician* Paulo Renato Guérios Master’s in Social Anthropology at PPGAS/Museu Nacional/UFRJ, currently a doctoral student at the same institution ABSTRACT This article discusses how the flux of cultural productions between centre and periphery works, taking as an example the field of music production in France and Brazil in the 1920s. The life trajectories of Jean Cocteau, French poet and painter, and Heitor Villa-Lobos, a Brazilian composer, are taken as the main reference points for the discussion. The article concludes that social actors from the periphery tend themselves to accept the opinions and judgements of the social actors from the centre, taking for granted their definitions concerning the criteria that validate their productions. Key words: Heitor Villa-Lobos, Brazilian Music, National Culture, Cultural Flows In July 1923, the Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos arrived in Paris as a complete unknown. Some five years had passed since his first large-scale concert in Brazil; Villa-Lobos journeyed to Europe with the intention of publicizing his musical output. His entry into the Parisian art world took place through the group of Brazilian modernist painters and writers he had encountered in 1922, immediately before the Modern Art Week in São Paulo. Following his arrival, the composer was invited to a lunch in the studio of the painter Tarsila do Amaral where he met up with, among others, the poet Sérgio Milliet, the pianist João de Souza Lima, the writer Oswald de Andrade and, among the Parisians, the poet Blaise Cendrars, the musician Erik Satie and the poet and painter Jean Cocteau. -

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism" Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)! Biographical sketch:! §" Born in St. Petersburg, Russia.! §" Studied composition with “Mighty Russian Five” composer Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov.! §" Emigrated to Switzerland (1910) and France (1920) before settling in the United States during WW II (1939). ! §" Along with Arnold Schönberg, generally considered the most important composer of the first half or the 20th century.! §" Works generally divided into three style periods:! •" “Russian” Period (c.1907-1918), including “primitivist” works! •" Neoclassical Period (c.1922-1952)! •" Serialist Period (c.1952-1971)! §" Died in New York City in 1971.! Pablo Picasso: Portrait of Igor Stravinsky (1920)! Ballets Russes" History:! §" Founded in 1909 by impresario Serge Diaghilev.! §" The original company was active until Diaghilev’s death in 1929.! §" In addition to choreographing works by established composers (Tschaikowsky, Rimsky- Korsakov, Borodin, Schumann), commissioned important new works by Debussy, Satie, Ravel, Prokofiev, Poulenc, and Stravinsky.! §" Stravinsky composed three of his most famous and important works for the Ballets Russes: L’Oiseau de Feu (Firebird, 1910), Petrouchka (1911), and Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1913).! §" Flamboyant dancer/choreographer Vaclav Nijinsky was an important collaborator during the early years of the troupe.! ! Serge Diaghilev (1872-1929) ! Ballets Russes" Serge Diaghilev and Igor Stravinsky.! Stravinsky with Vaclav Nijinsky as Petrouchka (Paris, 1911).! Ballets -

A Level Schools Concert November 2014

A level Schools Concert November 2014 An Exploration of Neoclassicism Teachers’ Resource Pack Autumn 2014 2 London Philharmonic Orchestra A level Resources Unauthorised copying of any part of this teachers’ pack is strictly prohibited The copyright of the project pack text is held by: Rachel Leach © 2014 London Philharmonic Orchestra ©2014 Any other copyrights are held by their respective owners. This pack was produced by: London Philharmonic Orchestra Education and Community Department 89 Albert Embankment London SE1 7TP Rachel Leach is a composer, workshop leader and presenter, who has composed and worked for many of the UK’s orchestras and opera companies, including the London Sinfonietta, the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Wigmore Hall, Glyndebourne Opera, English National Opera, Opera North, and the London Symphony Orchestra. She studied at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, at Opera Lab and Dartington. Recent commissions include ‘Dope Under Thorncombe’ for Trilith Films and ‘In the belly of a horse’, a children’s opera for English Touring Opera. Rachel’s music has been recorded by NMC and published by Faber. Her community opera ‘One Day, Two Dawns’ written for ETO recently won the RPS award for best education project 2009. As well as creative music-making and composition in the classroom, Rachel is proud to be the lead tutor on the LSO's teacher training scheme for over 8 years she has helped to train 100 teachers across East London. Rachel also works with Turtle Key Arts and ETO writing song cycles with people with dementia and Alzheimer's, an initiative which also trains students from the RCM, and alongside all this, she is increasingly in demand as a concert presenter. -

School of Music Program Notes

First Half Deanna Buringrud,flute Gail Novak,piano Honors Project Recital Hall I April 7, 2019 j 12 p.m. Program Sonata for Flute and Piano Francis Poulenc Allegro malinconico Cantilena Presto giocoso First Sonata, for Flute and Piano Bohuslav Martinu I II III INTERMISSION ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY School of Music Program Notes First Sonata for Flute and Piano, Bohuslav Marinu (Dec. 1890 - 1959) Bohuslav Marinu was a Czech composer of early-mid 20th century. Bohuslav grew up in a family without material wealth. He began violin at a young age and excelled quickly. The town was impressed by his talent when attending his recitals, and raised the funds to send him to the Prague Conservatory in 1906. Martinu was expelled from the Prague conservatory in 1910 due to "incorrigible negligence." Martinu became more interested in the composition aspect of music than his individual performance, and as such did not practice his violin enough. First Sonata for Flute and Piano was composed in 1945 in South Orleans, Cape Cod. During this time, Marinu was living in the United States to escape France when it was occupied by the Nazis in WW2. Though he didn't speak english very well, Martinu quickly adapted to his environment and ended up teaching both at Princeton and the Tanglewood institution in Berkshire. First Sonata was written for Georges Laurent, the principle flutist of the Boston Symphony. It premiered in New York 1949. Remnants ofMartinu's past can be heard throughout the sonata, such as the perfect fourths in the first movement that represent the church bells his father rang. -

Program Notes by Dr

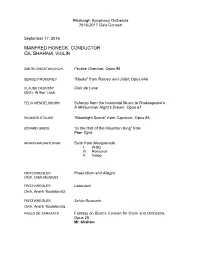

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Gala Concert September 17, 2016 MANFRED HONECK, CONDUCTOR GIL SHAHAM, VIOLIN DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Festive Overture, Opus 96 SERGEI PROKOFIEV “Masks” from Romeo and Juliet, Opus 64a CLAUDE DEBUSSY Clair de Lune Orch. Arthur Luck FELIX MENDELSSOHN Scherzo from the Incidental Music to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Opus 61 RICHARD STAUSS “Moonlight Scene” from Capriccio, Opus 85 EDVARD GREIG “In the Hall of the Mountain King” from Peer Gynt ARAM KHACHATURIAN Suite from Masquerade I. Waltz IV. Romance V. Galop FRITZ KREISLER Praeludium and Allegro Orch. Clark McAlister FRITZ KREISLER Liebesleid Orch. André Kostelanetz FRITZ KREISLER Schön Rosmarin Orch. André Kostelanetz PABLO DE SARASATE Fantasy on Bizet’s Carmen for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 25 Mr. Shaham Sept. 17, 2016, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Festive Overture, Opus 96 (1954) Among the grand symphonies, concertos, operas and chamber works that Dmitri Shostakovich produced are also many occasional pieces: film scores, tone poems, jingoistic anthems, brief instrumental compositions. Though most of these works are unfamiliar in the West, one — the Festive Overture — has been a favorite since it was written in the autumn of 1954. Shostakovich composed it for a concert on November 7, 1954 commemorating the 37th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but its jubilant nature suggests it may also have been conceived as an outpouring of relief at the death of Joseph Stalin one year earlier. One critic suggested that the Overture was “a gay picture of streets and squares packed with a young and happy throng.” As its title suggests, the Festive Overture is a brilliant affair, full of fanfare and bursting spirits. -

La Voix Humaine Digital Premiere Oct

Francis Poulenc La Voix HumaIne Digital Premiere Oct. 24, 2020 | 7:30pm 2020–2021 DIGITAL SEASON REIMAGINED FOR THE SCREEN CANADA’S ONLY 5-TIME WINNER OF WINERY OF THE YEAR Since 1981, Mission Hill Family Estate has pioneered British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley as a premium wine making region. Founded by Proprietor Anthony von Mandl, the iconic family-owned winery is known as Canada’s only 5-time winner of the Winery of the Year Award by WineAlign Canada. Guests can experience international award-wining wines and indulge in an epicurean adventure all while enjoying the panoramic views of mountains, lakes, and vineyards. MISSIONHILLWINERY.COM Francis Poulenc La Voix HumaIne Tom Wright, General Director Jonathan Darlington, Music Director Emeritus CONTENTS VO Administration and Ticket Centre 6 Cast & Creative 19 Behind the Scenes The Michael and Inna O’Brian Centre for Team Vancouver Opera 21 Patron Information 1945 McLean Drive 7 Production Team Vancouver, BC, V5N 3J7 22 VO Board & Staff Administration 8 Synopsis T: 604 682 2871 F: 604 682 3981 9 Notes from the Creative Team VO Ticket Centre Sponsored by Mission Hill Family Estate T: 604 683 0222 10 Biographies [email protected] www.vancouveropera.ca 15 Opera in Context 16 Opera Allsorts Vancouver Opera acknowledges that we work and perform on the unceded and traditional territory of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations. Publication Manager Vincent Wong Design & Layout Annie Mack Vancouver Opera is a professional company. It operates under the jurisdiction of Canadian Actors’ Equity Association, Vancouver Musicians’ Association, and IATSE, and is a member of OPERA America and Opera.ca 2020–2021 DIGITAL SEASON Privacy Vancouver Opera is committed to REIMAGINED FOR THE SCREEN protecting your privacy.