Analysis of Gluten in Dried Yeast and Yeast-Containing Products

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHORT-CUT VEGAN! SHORT-CUT VEGAN PANTRY Sauce, Hoisin Sauce, Curry Paste, People Frequently Request Tips on How ITEMS Chutney, Etc

SHORT-CUT VEGAN! SHORT-CUT VEGAN PANTRY sauce, hoisin sauce, curry paste, People frequently request tips on how ITEMS chutney, etc. to incorporate vegan meals into a busy All of these items can figure as •Nutritional yeast (available in bulk, or in schedule. A number of cookbooks tackle ingredients in quick, delicious vegan meals. bag or jar ) this question, including Maribeth Abrams In your vegetable larder •Plant milks in aseptic packages and Anne Dinshah, The 4 Ingredient Vegan; •Cabbage and carrots last a long time in the •Canned coconut milk Nava Atlas, Vegan Express; Kathy Hester, refrigerator and can form a centerpiece •Dried fruits The Easy Vegan Cookbook; Lorna Sass, or addition to many meals. Potatoes, •Dried herbs and spices Short-Cut Vegetarian, re-released as Short- sweet potatoes, onions and garlic last a QUICK VEGAN MEALS Cut Vegan; and Robin Robertson’s Quick- long time at at room temperature. Come up with a list of 6 to 10 quick meals Fix Vegetarian, Quick-Fix Vegan, and More Store potatoes away from the light. that lend themselves to many variations, that you Quick-Fix Vegan (all different). Most are In the freezer: can rotate through. Think ethnic: available in the Monroe County Library •Frozen vegetables, especially peas, corn •Chinese/Asian--stir-fry with brown rice System, as well as from book sellers. Here’s and spinach which compare well with •Indian--curry with brown rice a distillation of the advice found in those fresh. •Italian--pasta with tomato sauce or pesto books. •Frozen pie crusts or doughs; frozen pizza and veggies In the refrigerator: •Middle Eastern--hummus with tabouleh TIPS FOR EFFICIENT COOKING •Soy products and other meat analogues: •Mexican/Latin--beans and rice/tacos/ Keep an organized kitchen and pantry. -

Eating Well to Prevent Vitamin B12 Deficiency

www.healthinfo.org.nz Eating well to prevent vitamin B12 deficiency Vitamin B12 helps keep your body's nerve and blood cells healthy. It helps make DNA, the genetic material in your cells. It also helps prevent a type of anaemia that can make you feel tired and weak. Causes of vitamin B12 deficiency Normally, your stomach and intestines digest and absorb vitamin B12 from your food. Vitamin B12 deficiency happens when your stomach and intestines can't absorb the vitamin. This can happen if any of the following apply. ▪ You have pernicious anaemia. This is where your body destroys the cells in your stomach that help you absorb vitamin B12. ▪ You have had surgery to remove part of your stomach or the last part of your small intestine. ▪ You have a digestive disorder such as coeliac disease or Crohn's disease. ▪ You are on certain long-term medications that make it harder for your body to absorb vitamin B12. These medications include antacids, heartburn medicines such as omeprazole and pantoprazole, and metformin. ▪ You are 65 or older. Vitamin B12 deficiency can also happen if you don't eat enough foods with vitamin B12. Most people in New Zealand get plenty of vitamin B12 from food. But some people might not get enough. These people include: ▪ vegans or strict vegetarians ▪ babies who are breastfed by mothers who are vegan or strict vegetarians ▪ people who eat little or no animal foods ▪ older people who have a poor appetite and eat very small meals. Treating vitamin B12 deficiency Vitamin B12 deficiency is diagnosed through a blood test. -

Yeast Extract a Treasure from Nature for Food

YEAST EXTRACT A TREASURE FROM NATURE FOR FOOD WHITE PAPER Content I. What is yeast extract? P. 4 A few definitions and historical facts Yeast definition Yeast has been used as a natural origin food ingredient for centuries Yeast extract as a natural flavoring ingredient Yeast extract is an ingredient from nature Yeast extract is coming from yeast Composition of yeast extract Yeast extract as a food ingredient Natural ingredient Yeast extract and gluten 100% vegan An ingredient which fits a non-GMO approach A Halal and Kosher certified ingredient Process resistant II. How is yeast extract produced? P. 8 Fermentation Breakage Separation Different forms of yeast extract III. What are the main uses of yeast extract? P.12 Yeast extract main applications in food industries A natural and culinary ingredient from yeast Yeast extract in your kitchen Taste What is taste? What is yeast extract taste? Zoom on the diversity of yeast extract tastes Focus on umami taste How does yeast extract improve taste in food? Let us see the properties of yeast extract with a few examples of recipes Nutritional profile improvement Major public health issues explain current trends in nutrition Salt reduction Sugar reduction Fat reduction Clean label IV. Biospringer is an expert of yeast extract P.20 Our technical expertise Expert on taste building Local teams worldwide | Biospringer WHITE PAPER owadays, food manufacturers have several challenges to Nface when responding to consumer trends. Consumers are more and more careful about the composition and the quality of the products they eat: naturalness, nutrition and pleasure are essential criteria in the purchase decision. -

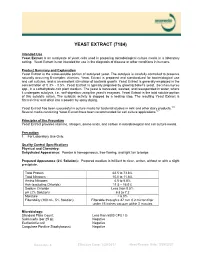

Yeast Extract, Product Information

YEAST EXTRACT (7184) Intended Use Yeast Extract is an autolysate of yeast cells used in preparing microbiological culture media in a laboratory setting. Yeast Extract is not intended for use in the diagnosis of disease or other conditions in humans. Product Summary and Explanation Yeast Extract is the water-soluble portion of autolyzed yeast. The autolysis is carefully controlled to preserve naturally occurring B-complex vitamins. Yeast Extract is prepared and standardized for bacteriological use and cell cultures, and is an excellent stimulator of bacterial growth. Yeast Extract is generally employed in the concentration of 0.3% - 0.5%. Yeast Extract is typically prepared by growing baker’s yeast, Saccharomyces spp., in a carbohydrate-rich plant medium. The yeast is harvested, washed, and resuspended in water, where it undergoes autolysis, i.e., self-digestion using the yeast’s enzymes. Yeast Extract is the total soluble portion of this autolytic action. The autolytic activity is stopped by a heating step. The resulting Yeast Extract is filtered clear and dried into a powder by spray drying. Yeast Extract has been successful in culture media for bacterial studies in milk and other dairy products.1-5 Several media containing Yeast Extract have been recommended for cell culture applications.6,7 Principles of the Procedure Yeast Extract provides vitamins, nitrogen, amino acids, and carbon in microbiological and cell culture media. Precaution 1. For Laboratory Use Only. Quality Control Specifications Physical and Chemistry: Dehydrated Appearance: Powder is homogeneous, free-flowing, and light tan to beige. Prepared Appearance (2% Solution): Prepared medium is brilliant to clear, amber, without or with a slight precipitate. -

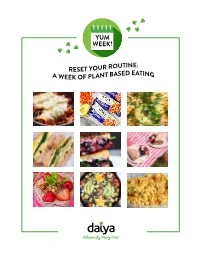

Yum Week! Your Plant Based Week at a Glance

YUM WEEK! YOUR PLANT BASED WEEK AT A GLANCE Breakfast Lunch Dinner DAY Yogurt Parfait Daiya Santa Fe Creamy Macaroni and Cheeze 1 Burrito Cheezy Vegan Leftover Creamy Bualo Cauliflower Pizza DAY Breakfast Sandwich Mac n Cheeze 2 Daiya Fiesta Vegetable Wrap Balsamic Berry Vegan DAY Breakfast Burrito Grilled Cheeze 3 Cheezy Vegan Daiya Santiago Baked Bualo DAY Breakfast Sandwich Burrito Cheezy Mac 4 Daiya Homestyle Leftover Bualo Bacon Avocado DAY Breakfast Burrito Cheezy Mac Casserole 5 Cheezy Vegan Vegetable Wrap or Black Bean Enchiladas DAY Breakfast Sandwich Leftover Casserole 6 Breakfast Layered Garden Salad Daiya Frozen Pizza DAY Style Hash w/ Cheeze Stick 7 ADD TO CART FOR QUICK AND EASY PLANTBASED MEALS BREAKFAST BREAKFAST Yogurt Parfait PREP 5 TOTAL 5 SERVES 1 INGREDIENTS 1 container of Daiya Yogurt Alternative Fruit of choice Nut Butter (optional) Granola of choice BREAKFAST Cheezy Vegan Breakfast Sandwich PREP 30 COOK 20 TOTAL 50 SERVES 4 INGREDIENTS LET’S MAKE IT 1 Package Daiya Cheddar Style Slices Press tofu between paper towels or cloth for 1 Block Tofu, (Cut into 4 slices) 30 minutes to remove excess moisture. 1/2 tsp turmeric 1 avocado, (Sliced) Preheat oven to 400 degrees. 1 Handful fresh spinach 4 Gluten-free bagels, (or English Mun) Combine salt, turmeric, nutritional yeast, black pepper 3-4 tsp extra virgin olive oil, (split between the tofu and a bit of water. and tempeh skillets) salt, (to taste) Coat tofu slices to mixture and let sit for about black pepper, (to taste) 2-3 minutes before baking. nutritional yeast, (to taste) Bake tofu for about 20 minutes. -

Mondelēz Union Network

Mondelēz Union Network What is ? Mondelez is a global snack foods company which came into being on October 2, 2012 when the former Kraft Foods Inc. was split into two, resulting in the creation of two separate companies, both headquartered in the USA. Mondelēz took the “snacks” products (biscuits, confectionery, salty crackers, nuts, gum, Tang), giving it about two-thirds the revenue of the former Kraft. The remaining “grocery” products were stuffed into a North American (only) company now known as Kraft Foods Group. Former Kraft CEO Irene Rosenfeld now heads up Mondelēz. If you worked for the former Kraft or one of its subsidiaries manufacturing or distributing snack products, including former Danone or Cadbury products, you now work for Mondelēz or one of its subsidiaries. In some countries, the name change will not be immediate. Mondelēz Kraft Foods Group Oreo, Chips Ahoy, Fig Kraft macaroni and cheese Newtons, SnackWell’s, Stove Top stuffing Nilla wafers, Mallomars Kool-Aid and Capri Sun Nabisco crackers including drinks Ritz, Triscuit, Teddy Grahams, Deli brands including Oscar Honey Maid, Premium Mayer, Louis Rich, saltines, Planters nuts, Lunchables, Deli Creations, Cheese Nips, Wheat Thins, Claussen pickles Lu biscuits Philadelphia cream cheese Philadelphia cream cheese Kraft, Velveeta and Cracker Toblerone chocolate, Milka Barrel cheese candy bars, Cadbury, Green and Black’s Jell-O Trident/ Dentyne gum Cool Whip/Miracle Whip Halls A-1 steak sauce, Grey Poupon mustard Tang Vegemite Jacobs coffee Maxwell House coffee 888 Brand names in red are ‘power brands’ each generating revenue over USD 1 billion In North America, Maxwell House coffee is ‘grocery’ (Kraft Foods Group), but elsewhere coffee is Mondelēz. -

PLANT-BASED Burgers Au Naturel

PLANT-BASED burgers au naturel 34 THE NATIONAL CULINARY REVIEW • MAY/JUNE 2018 BURGERS AU NATUREL BY OFFERING A PLANT-BASED BURGER ON THE MENU, YOU TELL A GROWING NUMBER OF CUSTOMERS THAT YOU KNOW WHERE THEY’RE COMING FROM. BY JODY SHEE ith all the eating styles of the day, your customers don’t have Wto be vegetarians to appreciate a good non-beef, plant-based burger. Thus, it may be time to add one to your menu. But where do you start, especially considering that not all customers think the same way about what you might come up with? Chicago’s The Growling Rabbit has a large vegetarian and vegan customer base, so it was only natural for owner Laura Soncrant to develop a plant-based patty and offer it as a non-beef burger option. She came up with a pink bean and quinoa patty for her brunch-pub/supper-club operation. She began asking guests why they ordered what they did, and discovered that older consumers who choose to switch out the beef patty for a plant-based one do so for health reasons— Photo by Chris Casella/Courtesy of Melt Bar and Grilled limiting their meat for the day or for the week. Younger consumers who select the plant-based patty often do so with a mindfulness of excessive water use in beef production—a less environmentally sustainable practice than raising plants. Travis Johnson, CEC, executive culinary director of Sodexo- managed Seminole Dining, with 36 dining outlets at Florida State University, Tallahassee, believes that chefs’ sustainability ethos should extend beyond buying fresh and local ingredients to include exploring and incorporating non-animal proteins. -

Alcoholic Beverages and Their Role in the Culinary Technology

Science and Technology Publishing (SCI & TECH) ISSN: 2632-1017 Vol. 3 Issue 10, October - 2019 Alcoholic beverages and their role in the culinary technology Aneta Popova Department of Catering and tourism University of food technologies Plovdiv, Bulgaria [email protected] Abstract—Countries are very attached to their New recyclable packages are increasing their traditions and their diets are influenced by various presence in the food production chain [3]. More factors i.e. product diversity, climate change, food efficient processes, in terms of energy, water use, availability, historical dishes. Consumers waste reduction, and repurposing byproducts, have to nowadays have much greater expectations and be included in culinary technology. Manufacturers and less trust. Organic, bio and fair trade are only a culinary specialists are fighting for zero-waste food few of the terms gaining popularity in the food processing cycles. chain production circle. The ultimate goal is a Alcoholic beverages have served as sources of sustainable food production and healthy diets. medicine and nutrients [4]. Fermented fruit/grains are in the base of alcohol making. Evidence of alcoholic The purpose of this review was to present the beverages are found in many places throughout ways alcoholic beverages are incorporated in history i.e. China, India, Greece, etc. [5]. Cacao fruit, dishes from different regions and nationalities as for instance, was used to produce wine around 1400 well as to provide knowledge about the properties BC. Cacao wine, also known as theobroma, was alcohol can exhibit while being an ingredient to a valuable to the Aztecs and used in religious dish. This paper also introduces alcohol as a ceremonies [6]. -

Plumeria Beach House 2016 Autumn Menu

In Room Dining Menu 11am to 10:00pm Starters Poke, Chip and Dip 15 gf df Kahala Salad Caesar 15 nf ahi poke, chicharrones, sriracha mayo romaine lettuce, focaccia bread croutons, parmesan cheese, caesar dressing Ahi Sashimi market price daikon, wasabi, picked ginger Kahala Green Salad 12 gf df nf kula green, tomates, house dressing Comfort Soups Hawaiian Style Noodle Soup 22 nf df Soup of the Day 14 “sun brand” noodles, smoked hoisin char siu, green onion, bok choi, sweet egg omelet, nori, oxtail dashi broth Sandwiches Roast Turkey Club Sandwich 18 nf df Bruddah Dave’s Taro Burger 24 vegan gf nd df ef roasted turkey, avocado, sprouts, BLT mayo, toasted grilled taro burger, nutritional yeast, roasted portobello, organic sprouted 12 grain bread tomatoes, upcountry greens, balsamic dressing Bacon Cheese Burger 22 nf Grilled Island Catch Sandwich MP custom beef blend, white cheddar, sweet soy glaze, asian remoulade , grilled sweet onion, local greens, horseradish cream, lettuce , tomato, toasted brioche tomato, brioche Pan Pizza Design Your Own Pizza 23 bell peppers, mushrooms, onions, olives, pineapple, ham, pepperoni, tomatoes (add $1 per topping) Marghreta Pizza 23 mozzarella cheese, fresh tomatoes and basil Entrées CAB Signature New York “Steak Frites” 44 gf nf ef Macadamia Nut Butter Glazed Pacific Lobster Tail 38 ef farmer’s seasonal vegetables, french fries, red wine asparagus whipped potatoes, macadamia nut butter jus sauce Kalua Salt, Rosemary and Garlic Roasted Half Grilled Catch of the Day 32 nf ef Chicken 29 gf nf ef farmer’s -

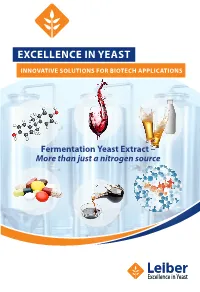

Fermentation Yeast Extract – More Than Just a Nitrogen Source Yeast Extracts – What Makes Them Unique?

EXCELLENCE IN YEAST INNOVATIVE SOLUTIONS FOR BIOTECH APPLICATIONS Fermentation Yeast Extract – More than just a nitrogen source Yeast Extracts – What makes them unique? In the complex world of biotechnology and fermen- product. Yeast extract from brewers’ yeast is charac- tation, Leiber brewers’ yeast extracts have proven to terized by a high sustainability and thus the manu- be more than just a nitrogen source! Yeast extracts facturing can be regarded as ecologically valuable have a long tradition in the fermentation industry, and efficient. serving as a nutritious and effective complex nit- rogen source for a broad spectrum of production microorganisms belonging to bacteria, fungi and yeasts. The production of beer, and thus the production of the by-product brewers’ yeasts is carried out mainly on the basis of renewable, natural raw materials such as barley, hops and water. The solids, including mainly the yeast biomass, remain in the tank as by- Yeast extract composition and their benefits Building blocks for biosynthesis Important growth factors Supply of nitrogen Metabolic driver Proteins & Nucleotides free amino acids Essential enzymatic cofactors for biocatalytic activities Vitamins & Minerals & Derivatives Pace maker of fermentation Traces Impacting and regulating intracellular transport processes Cell protection Carbohydrates & Derivatives Maintaining electrical potential via Storage compounds membranes Enzymatic cofactors Cell protection against stress, osmotic pressure, free radicals Yeast cell wall Brewers’ yeast cell wall consists of a substantially complex structure containing many interesting and functional components, such as β-1,3- and β-1,6-linked glucan, mannans, mannoproteins, sterols and phospholipids. All these components present a multitude of interesting functions, which serve as versatile tools among others in the field of wine production including clarification, improving fermentation performance and flavoring. -

Vegetarian Teens

RD Resources for Consumers: Vegetarian Teens Vegetarian Meal Ideas Breakfast Teenagers represent the fastest growing segment of • Cereal with soymilk, or cow’s milk vegetarians in the United States. • Whole-wheat toast with margarine or jelly and a piece of fruit Many teens choose a vegetarian diet because of • Instant oatmeal with nuts, raisins, and soymilk or environmental and ethical concerns regarding meat cow’s milk production and consumption. With some planning, a vegetarian diet can provide you with all the nutrients you Lunch need and foods you enjoy. • Vegetable sandwich (tomatoes, peppers, onions, avocado) with or without cheese on whole-grain bread • Vegetable soup with a piece of toast Types of Vegetarians • Veggie burger or falafel with soy cheese, mushrooms, and tomato on a whole-grain bun Lacto-ovo: Includes dairy products such as milk, cheese, • Pita bread filled with veggies or peanut butter yogurt, and eggs but excludes meat, poultry, and fish. • Chili with beans and textured vegetable protein Lacto: Includes dairy products but excludes eggs and foods containing eggs as well as meat, poultry and fish. Dinner Vegan: Includes only foods of plant origin and excludes meat • Tofu stir-fry with brown rice or animal products such as milk or eggs. A vegan diet consists • Pasta with tomato sauce plus vegetables (mushrooms, of fruits, vegetables, beans, grains, seeds, and nuts. tomatoes, eggplant, peppers, and onions) • Tacos or burritos filled with beans, textured vegetable protein, tofu, or tempeh Eating a Healthy Diet • Pizza with or without cheese and topped with vegetables, tofu, or meat substitute Choose a variety of foods, including whole-grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, and seeds using the Vegetarian Snacks Food Pyramid found at: • Dried fruits http://www.mypyramid.gov/pyramid/vegetarian.html • Trail mix • Popcorn If you consume milk or dairy products, choose low-fat or fat- • Rice cakes free products. -

The Market Achievements History

Limited umbrella, and the company has consistently reinforced the food value and "Australian-ness" ofVegemite. Soon after that, the song which was to secure Vegemite's place in the Australian heart forever was introduced. This was the "Happy Little Vegemites", a delightful, toe-tapping little tune which has since seen service in many advertising campaigns on radio and television. THE PRODUCT The original Vegemite concentrated yeast extract recipe devised by Dr Cyril Callister in 1923 remains vittually tmchanged. Vegemite is tich in protein and ONE OF THE WORLD ' S RICHEST KNOWN SOURCES OF VITAMIN B. minerals. 8 complex vitamins added to Vegemite are fights with the men up north! If you are one of key part of growing up in this country for nearly THE MARKET that it was time to tackle the concentrated yeast health centres across the nation were even essential in the body's use of carbohydrates. Few those who don't need Vegemite medicinally, then eve1y child. It has become a prominent ingredient In the Australian market, Vegemite* is the generic spread market, and in 1923 he hired Cyril P. Callister recommending it as an ideal food supplement for other foods can match Vegemite's contribution to thousands of invalids are asking you to deny in the Australian family diet, and is appropriately tem1 for yeast spreads. It is the one spread that is to develop an Australian yeast spread. both babies and nursing mothers. Australians of the diet. While it is true that Vegemite contains salt, yourself of it for the time being." represented by happy and well-nourished children.