Sem T.Tulo-3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2012 Version Available for Download From

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2012 version Available for download from http://www.ramsar.org/ris/key_ris_index.htm. Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework and guidelines for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 14, 3rd edition). A 4th edition of the Handbook is in preparation and will be available in 2009. 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY Beatriz de Aquino Ribeiro - Bióloga - Analista Ambiental / [email protected], (95) Designation date Site Reference Number 99136-0940. Antonio Lisboa - Geógrafo - MSc. Biogeografia - Analista Ambiental / [email protected], (95) 99137-1192. Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade - ICMBio Rua Alfredo Cruz, 283, Centro, Boa Vista -RR. CEP: 69.301-140 2. -

Check List 5(2): 222–237, 2009

Check List 5(2): 222–237, 2009. ISSN: 1809-127X LISTS OF SPECIES Birds (Aves), Serrania Sadiri, Parque Nacional Madidi, Depto. La Paz, Bolivia Peter Andrew Hosner 1 Kenneth David Behrens 2 A. Bennett Hennessey 3 1 University of Kansas, Museum of Natural History, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Division of Ornithology. Dyche Hall, 1345 Jayhawk Blvd., University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 66046. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Tropical Birding, 1 Toucan Way. Bloubergrise 7441, South Africa. 3 Asociación Civil Armonía. Avenida Lomas de Arena, Casilla 3566, Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Abstract We surveyed the Serrania Sadiri for birds at elevations between 500-950m for a combined total of 15 days in three different months. The area surveyed was along the Tumupasa/San Jose de Uchupiamones trail at the edge of Parque Nacional Madidi in Depto. La Paz, Bolivia. We report observations of 231 species of birds detected by sight and sound, including many outlying ridge specialists. We report and present photographs of a new species for Depto. La Paz (Caprimulgis nigrescens), the second Bolivian localities for Porphyrolaema prophyrolaema, Zimerius cinereicapillus, and Basileuterus chrysogaster, and five new species records for Parque Nacional Madidi. Introduction Foothills and outlying ridges of the Andes are From the small village of Tumupasa (14°8'46" S, often very difficult or impossible to access. As a 67°53'17" W; 400 m a.s.l; Figures 1 and 2), an old result, many of the specialist bird species in these trail leads generally southwest over the Serrania areas are poorly known and some only recently Sadiri to the town of San Jose de Uchupiamones described, and these areas generally have unique (14°12'47" S, 68°03'14" W; 520 m a.s.l). -

Manaus, Brazil: Amazon Rainforest & River Islands

MANAUS, BRAZIL: AMAZON RAINFOREST & RIVER ISLANDS OCTOBER 8-21, 2020 ©2019 The Brazilian city of Manaus is nestled deep in the heart of the incomparable Amazon rainforest, the greatest avian-rich ecosystem on the planet! This colorful, bustling city is perfectly positioned at the junction of the world’s two mightiest rivers, the Amazon and Rio Negro, where vast quantities of the warm, black water of the Negro collide with immense volumes of cooler, silt-laden whitewater of the Amazon flowing down from the Andes. The two rivers flow side-by-side for kilometers before completely mixing (due to the major difference in temperature), forming the famous “wedding of the waters” where two species of freshwater dolphins are regularly seen, including the legendary Pink River Dolphin (males reaching 185 kilograms (408 lbs.) and 2.5 meters (8.2 ft.) in length). A male Guianan Cock-of-the-rock on a lek has to be one of the world’s most spectacular birds. © Andrew Whittaker Manaus, Brazil: Amazon Rainforest & River Islands, Page 2 The Amazon and its immense waterways have formed many natural biogeographical barriers to countless birds and animals, allowing for heightened speciation over countless millions of years. The result is a legion of distinctly different yet sibling species found on opposite river banks. Prime examples on this trip include Gilded versus Black-spotted barbets, Amazonian versus Guianan trogon, Black-necked versus Guianan red-cotinga, White-browed versus Dusky purpletufts, White-necked versus Guianan puffbird, Orange-cheeked versus Caica parrots, White-cheeked versus Rufous-throated antbird, and Rufous-bellied versus Golden-sided euphonia, etc., thus making Manaus a perfect base for the exploration of the exotic mega rich avifauna of the unique heart of Amazonia. -

PERU: Manu and Machu Picchu Aug-Sept

Tropical Birding Trip Report PERU: Manu and Machu Picchu Aug-Sept. 2015 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour PERU: MANU and MACHU PICCHU th th 29 August – 16 September 2015 Tour Leader: Jose Illanes Andean Cock-of-the-rock near Cock-of-the-rock Lodge! Species highlighted in RED are the ones illustrated with photos in this report. INTRODUCTION Not everyone is fortunate enough to visit Peru; a marvelous country that boasts a huge country bird list, which is second only to Colombia. Unlike our usual set departure, we started out with a daylong extension to Lomas de Lachay first, before starting out on the usual itinerary for the main tour. On this extra day we managed to 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-0514 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report PERU: Manu and Machu Picchu Aug-Sept. 2015 find many extra birds like Peruvian Thick-knee, Least Seedsnipe, Peruvian Sheartail, Raimondi’s Yellow- Finch and the localized Cactus Canastero. The first site of the main tour was Huacarpay Lake, near the beautiful Andean city of Cusco (accessed after a short flight from Lima). This gave us a few endemic species like Bearded Mountaineer and Rusty-fronted Canastero; along with other less local species like Many-colored Rush-tyrant, Plumbeous Rail, Puna Teal, Andean Negrito and Puna Ibis. The following day we birded along the road towards Manu where we picked up birds like Peruvian Sierra-Finch, Chestnut-breasted Mountain-Finch, Spot-winged Pigeon, and a beautiful Peruvian endemic in the form of Creamy-crested Spinetail. We also saw Yungas Pygmy-Owl, Black-faced Ibis, Hooded and Scarlet-bellied Mountain- Tanagers, Red-crested Cotinga and the gorgeous Grass-green Tanager. -

Mammalian and Avian Diversity of the Rewa Head, Rupununi, Southern Guyana

Biota Neotrop., vol. 11, no. 3 Mammalian and avian diversity of the Rewa Head, Rupununi, Southern Guyana Robert Stuart Alexander Pickles1,2, Niall Patrick McCann1 & Ashley Peregrine Holland1 1Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, School of Biosciences,Cardiff University, Museum Avenue, Cardiff, Wales, CF103AX Rupununi River Drifters, Karanambu Ranch, Lethem Post Office, Region 9, Rupununi Guyana 2Corresponding author: Robert Stuart Alexander Pickles, e-mail: [email protected] PICKLES, R.S.A., McCANN, N.P. & HOLLAND, A.L. Mammalian and avian diversity of the Rewa Head, Rupununi, Southern Guyana. Biota Neotrop. 11(3): http://www.biotaneotropica.org.br/v11n3/en/abstract?in ventory+bn00911032011 Abstract: We report the results of a short expedition to the remote headwaters of the River Rewa, a tributary of the River Essequibo in the Rupununi, Southern Guyana. We used a combination of camera trapping, mist netting and spot count surveys to document the mammalian and avian diversity found in the region. We recorded a total of 33 mammal species including all 8 of Guyana’s monkey species as well as threatened species such as lowland tapir (Tapirus terrestris), giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) and bush dog (Speothos venaticus). We recorded a minimum population size of 35 giant otters in five packs along the 95 km of river surveyed. In total we observed 193 bird species from 47 families. With the inclusion of Smithsonian Institution data from 2006, the bird species list for the Rewa Head rises to 250 from 54 families. These include 10 Guiana Shield endemics and two species recorded as rare throughout their ranges: the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) and crested eagle (Morphnus guianensis). -

Species Limits of the Least Pygmy-Owl (Glaucidium

Wilson Bull., 107(l), 1995, pp. 7-25 SPECIES LIMITS OF THE LEAST PYGMY-OWL (GLAUCZDZUM MZNUTZSSZMUM) COMPLEX STEVE N. G. HOWELL ’ AND MARK B. ROBBINS ’ ABSTRACT.-The Least Pygmy-Owl (Glaucidium minutissimum) complex comprises 10 described taxa that inhabit tropical and subtropical forests. Consistent song differences among taxa in this complex, supported by morphometric, plumage, and habitat data, indicate that, in addition to the recently described G. hardyi and G. parkeri, four species can be recognized in the Least Pygmy-Owl complex: G. palmarum of western Mexico (includes the described subspecies palmarum, oberholseri, and griscomi); G. sanchezi of northeastern Mexico; G. griseiceps of southeastern Mexico, Central America, and the Pacific slope of northern South America (includes the described subspecies griseiceps, rarum, and occul- turn); and G. minutissimum of southeastern Brazil and adjacent Paraguay. Received 8 Nov. 1993, accepted 9 May 1994. The genus Glaucidium comprises a number of species of small owls widespread in the Americas, Eurasia, and Africa. Four groups of mainland New World Glaucidium are generally recognized: the G. gnoma complex (western Canada to Honduras), the G. brusilianum complex (southwestern United States to southern South America), the G. minutissimum complex (Mexico to South America), and the G. jardinii complex (Costa Rica to South America) (Peters 1940, Meyer de Schauensee 1970, A.O.U. 1983, Sibley and Monroe 1990). Although the G. brusilianum complex stands out as relatively distinct by virtue of its streaked crown and proportion- ately longer tail with numerous pale bars, differences between the spotted- crowned gnoma and jardinii groups and the minutissimum group have been confused (e.g., Griscom 1931, Konig 1991). -

Part VI Teil VI

Part VI Teil VI References Literaturverzeichnis References/Literaturverzeichnis For the most references the owl taxon covered is given. Bei den meisten Literaturangaben ist zusätzlich das jeweils behandelte Eulen-Taxon angegeben. Abdulali H (1965) The birds of the Andaman and Nicobar Ali S, Biswas B, Ripley SD (1996) The birds of Bhutan. Zoo- Islands. J Bombay Nat Hist Soc 61:534 logical Survey of India, Occas. Paper, 136 Abdulali H (1967) The birds of the Nicobar Islands, with notes Allen GM, Greenway JC jr (1935) A specimen of Tyto (Helio- to some Andaman birds. J Bombay Nat Hist Soc 64: dilus) soumagnei. Auk 52:414–417 139–190 Allen RP (1961) Birds of the Carribean. Viking Press, NY Abdulali H (1972) A catalogue of birds in the collection of Allison (1946) Notes d’Ornith. Musée Hende, Shanghai, I, the Bombay Natural History Society. J Bombay Nat Hist fasc. 2:12 (Otus bakkamoena aurorae) Soc 11:102–129 Amadom D, Bull J (1988) Hawks and owls of the world. Abdulali H (1978) The birds of Great and Car Nicobars. Checklist West Found Vertebr Zool J Bombay Nat Hist Soc 75:749–772 Amadon D (1953) Owls of Sao Thomé. Bull Am Mus Nat Hist Abdulali H (1979) A catalogue of birds in the collection of 100(4) the Bombay Natural History Society. J Bombay Nat Hist Amadon D (1959) Remarks on the subspecies of the Grass Soc 75:744–772 (Ninox affinis rexpimenti) Owl Tyto capensis. J Bombay Nat Hist Soc 56:344–346 Abs M, Curio E, Kramer P, Niethammer J (1965) Zur Ernäh- Amadon D, du Pont JE (1970) Notes to Philippine birds. -

Characterization of DNA Microsatellite Variation in the Pygmy

MITOCHONDRIAL AND NUCLEAR ASSESSMENT OF FERRUGINOUS PYGMY-OWL (GLAUCIDIUM BRASILIANUM) PHYLOGEOGRAPHY A Dissertation by GLENN ARTHUR PROUDFOOT Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2005 Major Subject: Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences MITOCHONDRIAL AND NUCLEAR ASSESSMENT OF FERRUGINOUS PYGMY-OWL (GLAUCIDIUM BRASILIANUM) PHYLOGEOGRAPHY A Dissertation by GLENN ARTHUR PROUDFOOT Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved as to style and content by: Rodney L. Honeycutt Nova J. Silvy (Co-Chair of Committee) (Member) R. Douglas Slack Felipe Chavez-Ramirez (Co-Chair of Committee) (Member) Robert D. Brown (Head of Department) May 2005 Major Subject: Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences iii ABSTRACT Mitochondrial and Nuclear Assessment of Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl (Glaucidium brasilianum) Phylogeography. Glenn Arthur Proudfoot, B.S., University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point; M.S., Texas A&M University-Kingsville Co-Chairs of Advisory Committee: Dr. Rodney L. Honeycutt Dr. R. Douglas Slack Sequences of the cytochrome b gene and genotypes from 11 polymorphic microsatellite loci were used to assess phylogeographic variation in ferruginous pygmy-owls (Glaucidium brasilianum) from Arizona, Mexico, and Texas. Analysis of mtDNA indicated that pygmy-owl populations in Arizona and Texas are unique, with no shared haplotypes. Populations from Sonora and Sinaloa, Mexico, were distinct from remaining populations in Mexico and grouped closest to haplotypes in Arizona. Nested clade analysis of mtDNA sequence data indicated past fragmentation separated pygmy-owls into two major groups: 1) Arizona, Sonora and Sinaloa, Mexico, and 2) southwestern (Nayarit and Michoacan), south-central (Oaxaca and Chiapas), and eastern Mexico, along the eastern slope of the Sierra Madre Oriental from Texas to Central America. -

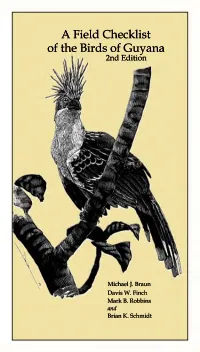

A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2Nd Edition

A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2nd Edition Michael J. Braun Davis W. Finch Mark B. Robbins and Brian K. Schmidt Smithsonian Institution USAID O •^^^^ FROM THE AMERICAN PEOPLE A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2nd Edition by Michael J. Braun, Davis W. Finch, Mark B. Robbins, and Brian K. Schmidt Publication 121 of the Biological Diversity of the Guiana Shield Program National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC, USA Produced under the auspices of the Centre for the Study of Biological Diversity University of Guyana Georgetown, Guyana 2007 PREFERRED CITATION: Braun, M. J., D. W. Finch, M. B. Robbins and B. K. Schmidt. 2007. A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana, 2nd Ed. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. AUTHORS' ADDRESSES: Michael J. Braun - Department of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 4210 Silver Hill Rd., Suitland, MD, USA 20746 ([email protected]) Davis W. Finch - WINGS, 1643 North Alvemon Way, Suite 105, Tucson, AZ, USA 85712 ([email protected]) Mark B. Robbins - Division of Ornithology, Natural History Museum, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA 66045 ([email protected]) Brian K. Schmidt - Smithsonian Institution, Division of Birds, PO Box 37012, Washington, DC, USA 20013- 7012 ([email protected]) COVER ILLUSTRATION: Guyana's national bird, the Hoatzin or Canje Pheasant, Opisthocomus hoazin, by Dan Lane. INTRODUCTION This publication presents a comprehensive list of the birds of Guyana with summary information on their habitats, biogeographical affinities, migratory behavior and abundance, in a format suitable for use in the field. It should facilitate field identification, especially when used in conjunction with an illustrated work such as Birds of Venezuela (Hilty 2003). -

SANTOS, Antonio Silveira R. Owls of Brazil

Birds- Owls of Brazil, by Antonio Silveira Owls of Brazil by Antonio Silveira As it is known by us, Brazil is the country that has the biggest biodiversity in the world, and one of the biggest in quantity of bird species, in a way that our bird fauna is too rich, and it is composed of many families and its enormous quality of species. Talking about the owls, there are in Brazil 38 forms among species and subspecies, which follow bellow. This list was done for helping birdwatchers. Publication in PDF of page of- www.aultimaarcadenoe.com.br - Copyrigth: Antonio Silveira R.dos Santos Birds- Owls of Brazil, by Antonio Silveira TYTONIDAE FAMILY Tyto alba (Suindara or Coruja-branca; Barn Owl). Cosmopolitan bird, existing almost all around the world, and existing all around Brazil. It mainly lives near human habitation, where it is used to nest at the church and towers. The voice looks like the sound of tearing a cloth, which usually emits in flying. Size: 37 cm. Two forms in Brazil: - Tyto alba tuidara. This form occurs at central and oriental Brazil. For the south area up to the Fire Land and west in Chile. - Tyto alba hellmagri. It occurs at Venezuela’s east and Guineas and from the extreme north up to the left bank of Amazonas River. STRIGIDAE FAMILY Megascops choliba; Corujinha-do-mato; Tropical Screech-Owl Occurs at Costa Rica to Bolivia, Paraguay and Argentina and all around Brazil, being one of the most common; in the forest board and near human habitation, where are a lot of insects attracted by the lights, mainly from the posts. -

Bolivia: Comprehensive Trip Report - 2015 1

RBT Bolivia: Comprehensive Trip Report - 2015 1 Bolivia Comprehensive Hooded Mountain Toucan by Alasdair Hunter RBT Bolivia: Comprehensive Trip Report - 2015 2 Chaco Pre-Tour: 28th August – 1st September 2015 Main Tour: 1st – 22nd September 2015 Apolo Post-Tour: 23rd to 27th September 2015 Trip report compiled by tour leader: Forrest Rowland Pre-Tour Top 5 Highlights Post-Tour Top 5 Highlights 1. Crested Gallito 1. Palkachupa Cotinga 2. Lark-like Brushrunner 2. Yungas Antwren 3. Cream-backed Woodpecker 3. Rufous-crested Coquette 4. Black-legged Seriema 4. Black-bellied Antwren 5. Many-colored Chaco Finch 5. Green-capped Tanager Main Tour Top 10 Highlights: 1. Hooded Mountain Toucan 6. Hairy-crested Antbird 2. Black-masked Finch 7. Ornate Tinamou 3. Black-hooded Sunbeam 8. Red-winged Tinamou 4. Blue-throated Macaw 9. Yungas Pygmy Owl 5. Red-fronted Macaw 10. Round-tailed Manakin Tour Intro Bolivia has a very distinctive allure. It does not have the longest list of birds of any South American country. It does not have the best infrastructure or accommodations of any South American country. It doesn’t even have a field guide to the birds of the country! However, Bolivia has more intrigue and potential than any other South American country. Bolivia has more barely accessed natural areas, more varied habitats yet to be explored, and more opportunity for visiting birders to actually contribute to the base of knowledge that is only very recently, and very slowly, being expanded by researchers and travelling birders alike. In short, Bolivia has quite a way to go in terms of creature comforts and access, but it is also an incredibly rewarding, mysterious, and fascinating country to explore! The above paragraph says nothing of the endless, impressive, awe-inspiring backdrop against which a birding adventure in Bolivia plays out. -

MAFX018 Metadata and Species.Xlsx

Filename Species description length Screaming Piha · Lipaugus vociferans M018AJ01 Amazon rainforest - Dense rainforest - Afternoon - Calm.wav Band-tailed Manakin · Pipra fasciicauda Calm afternoon in in dense tropical rainforest. Thick insect chorus and sparse bird calls punctuated by loud cicadas. Occasional branch snaps and flies buzzing. 471.9 Red-and-green Macaw · Ara chloropterus Crimson-crested Woodpecker · Campephilus melanoleucos Screaming Piha · Lipaugus vociferans Amazonian Trogon · Trogon ramonianus Band-tailed Manakin · Pipra fasciicauda M018AJ02 Amazon rainforest - Dense rainforest - Afternoon - Woodpecker.wav Plumbeous Pigeon · Patagioenas plumbea Calm afternoon in in dense tropical rainforest. Thick insect chorus and varied bird calls punctuated by woodpecker drumming. Occasional branch snaps and movement in the canopy. 353.74 Venezuelan red howler · Alouatta seniculus Amazonian Motmot · Momotus momota Bartlett's Tinamou · Crypturellus bartletti Barred Forest Falcon · Micrastur ruficollis Buff-throated Foliage-gleaner · Automolus ochrolaemus M018AJ03 Amazon rainforest - Dense rainforest - Dawn - Dawn chorus with howler monkeys.wav Small-billed Tinamou · Crypturellus parvirostris Busy dawn chorus in dense tropical rainforest. Loud insect chorus and howler monkey calls. Lush birdsong and fog drip. Occasional movement and branch snaps. 393.26 Screaming Piha · Lipaugus vociferans Ruddy Pigeon · Patagioenas subvinacea Plumbeous Pigeon · Patagioenas plumbea White-throated Toucan · Ramphastos tucanus Southern Mealy Amazon · Amazona