Sample Paper (Chicago Manual)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art Collection of Peter Watson (1908–1956)

099-105dnh 10 Clark Watson collection_baj gs 28/09/2015 15:10 Page 101 The BRITISH ART Journal Volume XVI, No. 2 The art collection of Peter Watson (1908–1956) Adrian Clark 9 The co-author of a ously been assembled. Generally speaking, he only collected new the work of non-British artists until the War, when circum- biography of Peter stances forced him to live in London for a prolonged period and Watson identifies the he became familiar with the contemporary British art world. works of art in his collection: Adrian The Russian émigré artist Pavel Tchelitchev was one of the Clark and Jeremy first artists whose works Watson began to collect, buying a Dronfield, Peter picture by him at an exhibition in London as early as July Watson, Queer Saint. 193210 (when Watson was twenty-three).11 Then in February The cultured life of and March 1933 Watson bought pictures by him from Tooth’s Peter Watson who 12 shook 20th-century in London. Having lived in Paris for considerable periods in art and shocked high the second half of the 1930s and got to know the contempo- society, John Blake rary French art scene, Watson left Paris for London at the start Publishing Ltd, of the War and subsequently dispatched to America for safe- pp415, £25 13 ISBN 978-1784186005 keeping Picasso’s La Femme Lisant of 1934. The picture came under the control of his boyfriend Denham Fouts.14 eter Watson According to Isherwood’s thinly veiled fictional account,15 (1908–1956) Fouts sold the picture to someone he met at a party for was of consid- P $9,500.16 Watson took with him few, if any, pictures from Paris erable cultural to London and he left a Romanian friend, Sherban Sidery, to significance in the look after his empty flat at 44 rue du Bac in the VIIe mid-20th-century art arrondissement. -

LIMBOUR, Georges (1900-1970)

LIMBOUR, Georges (1900-1970) Sources d’archives identifiées Source et outils de recherche : - Françoise NICOL, Georges Limbour. L’aventure critique, Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2014. - AGORHA (Accès Global et Organisé aux Ressources en Histoire de l’Art, INHA), en ligne. - CCfr (Catalogue Collectif de France), en ligne. Editée par Julien Bobot, 2015. Pour citer cet article : Françoise NICOL, « LIMBOUR, Georges (1900-1970). Sources d’archives identifiées », éditée par Julien Bobot, in Marie Gispert, Catherine Méneux (ed.), Bibliographies de critiques d’art francophones, mis en ligne en janvier 2017. URL : http://critiquesdart.univ-paris1.fr/georges- limbour AUSTIN (Texas), Harry Ransom Center Fonds Carlton Lake • 1 lettre de Georges Limbour à Jean Cassou, n.d. Fonds Carlton Lake, container 154.9 • 1 lettre de Georges Limbour à Roland Tual, n.d. Fonds Carlton Lake, container 286.9 LE HAVRE, Bibliothèque municipale Armand Salacrou Fonds Georges Limbour. Œuvres • Elocoquente : manuscrit original. 118 f. MS • La Chasse au mérou : manuscrit autographe et notes préparatoires. 142 f. MS inv. 1509 [numérisation sur le site « Lire au Havre ». URL : http://ged.lireauhavre.fr/?wicket:interface=:11] • Mélanges de Georges Limbour sur Dubuffet, 1949. Manuscrits autographes. [Comprend : « Complot de Minuit », « Les espagnols de Venise », « Mélanges Kahnweiler », « La nuit close », ainsi qu'une photocopie d'article.] MS inv. 1510 • Dossiers « Action 1945 ». Manuscrits autographes. [Ensemble des articles écrits par Georges Limbour pour la revue Action.] MS inv. 1511 • Dossier « Action 1946 ». Manuscrits autographes. [Ensemble des articles écrits par Georges Limbour pour la revue Action.] MS inv. 1512 • Dossier « Action 1947 ». Manuscrits autographes. [Ensemble des articles écrits par Georges Limbour pour la revue Action.] MS inv. -

Chapter 11 the Critical Reception of René Crevel

Chapter 11 The Critical Reception of René Crevel: The 1920s and Beyond Paul Cooke Born in 1900, Crevel was slightly too young to participate fully in the Dada movement.1 However, while fulfilling his military service in Paris’s Latour-Maubourg barracks, he met a number of young men – including François Baron, Georges Limbour, Max Morise and Roger Vitrac – who shared his interest in Dada’s anarchic spirit. On 14 April 1921 Crevel, Baron, and Vitrac attended the visite-conférence organized by the Dadaists at the Parisian church of Saint-Julien-le- Pauvre. Afterwards the three of them met up with Louis Aragon, one of the organizers of the afternoon’s event. As a result of this meeting the periodical aventure was born, with Crevel named as gérant. Only three issues would appear, with the editorial team splitting in February 1922 over the preparation of the Congrès du Palais (with Vitrac supporting Breton and the organizing committee, while Crevel and the others refused to abandon Tzara). Crevel would again defend Tzara against the proto-Surrealist grouping during the staging of Le Cœur à gaz at the Théâtre Michel in July 1923. At the very start of his career as a writer, therefore, it is clear that Dada was a significant influence for Crevel.2 However, despite siding with Tzara in the summer of 1923, it would not be long before Crevel was reconciled with Breton, with the latter naming him in the 1924 Manifeste as one of those who had “fait acte de SURRÉALISME ABSOLU” (Breton 1988: 328). It is as a Surrealist novelist and essayist that Crevel is remembered in literary history. -

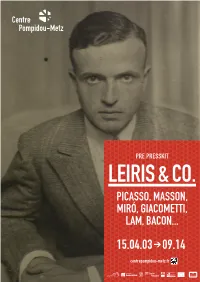

15.04.03 >09.14

PRE PRESSKIT LEIRIS & CO. PICASSO, MASSON, MIRÓ, GIACOMETTI, LAM, BACON... > 15.04.03 09.14 centrepompidou-metz.fr CONTENTS 1. EXHIBITION OVERVIEW ......................................................................... 2 2. EXHIBITION LAYOUT ............................................................................ 4 3. MICHEL LEIRIS: IMPORTANT DATES ...................................................... 9 4. PRELIMINARY LIST OF ARTISTS ........................................................... 11 5. VISUALS FOR THE PRESS ................................................................... 12 PRESS CONTACT Noémie Gotti Communications and Press Officer Tel: + 33 (0)3 87 15 39 63 Email: [email protected] Claudine Colin Communication Diane Junqua Tél : + 33 (0)1 42 72 60 01 Mél : [email protected] Cover: Francis Bacon, Portrait of Michel Leiris, 1976, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris © The Estate of Francis Bacon / All rights reserved / ADAGP, Paris 2014 © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Bertrand Prévost LEIRIS & CO. PICASSO, MASSON, MIRÓ, GIACOMETTI, LAM, BACON... 1. EXHIBITION OVERVIEW LEIRIS & CO. PICASSO, MASSON, MIRÓ, GIACOMETTI, LAM, BACON... 03.04 > 14.09.15 GALERIE 3 At the crossroads of art, literature and ethnography, this exhibition focuses on Michel Leiris (1901-1990), a prominent intellectual figure of 20th century. Fully involved in the ideals and reflections of his era, Leiris was both a poet and an autobiographical writer, as well as a professional -

Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness

summer 1998 number 9 $5 TREASON TO WHITENESS IS LOYALTY TO HUMANITY Race Traitor Treason to whiteness is loyaltyto humanity NUMBER 9 f SUMMER 1998 editors: John Garvey, Beth Henson, Noel lgnatiev, Adam Sabra contributing editors: Abdul Alkalimat. John Bracey, Kingsley Clarke, Sewlyn Cudjoe, Lorenzo Komboa Ervin.James W. Fraser, Carolyn Karcher, Robin D. G. Kelley, Louis Kushnick , Kathryne V. Lindberg, Kimathi Mohammed, Theresa Perry. Eugene F. Rivers Ill, Phil Rubio, Vron Ware Race Traitor is published by The New Abolitionists, Inc. post office box 603, Cambridge MA 02140-0005. Single copies are $5 ($6 postpaid), subscriptions (four issues) are $20 individual, $40 institutions. Bulk rates available. Website: http://www. postfun. com/racetraitor. Midwest readers can contact RT at (312) 794-2954. For 1nformat1on about the contents and ava1lab1l1ty of back issues & to learn about the New Abol1t1onist Society v1s1t our web page: www.postfun.com/racetraitor PostF un is a full service web design studio offering complete web development and internet marketing. Contact us today for more information or visit our web site: www.postfun.com/services. Post Office Box 1666, Hollywood CA 90078-1666 Email: [email protected] RACE TRAITOR I SURREALIST ISSUE Guest Editor: Franklin Rosemont FEATURES The Chicago Surrealist Group: Introduction ....................................... 3 Surrealists on Whiteness, from 1925 to the Present .............................. 5 Franklin Rosemont: Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness ............ 19 J. Allen Fees: Burning the Days ......................................................3 0 Dave Roediger: Plotting Against Eurocentrism ....................................32 Pierre Mabille: The Marvelous-Basis of a Free Society ...................... .40 Philip Lamantia: The Days Fall Asleep with Riddles ........................... .41 The Surrealist Group of Madrid: Beyond Anti-Racism ...................... -

Botting Fred Wilson Scott Eds

The Bataille Reader Edited by Fred Botting and Scott Wilson • � Blackwell t..b Publishing Copyright © Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 1997 Introduction, apparatus, selection and arrangement copyright © Fred Botting and Scott Wilson 1997 First published 1997 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 Blackwell Publishers Ltd 108 Cowley Road Oxford OX4 IJF UK Blackwell Publishers Inc. 350 Main Street Malden, MA 02 148 USA All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form Or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any fo rm of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Ubrary. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Bataille, Georges, 1897-1962. [Selections. English. 19971 The Bataille reader I edited by Fred Botting and Scott Wilson. p. cm. -(Blackwell readers) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-631-19958-6 (hc : alk. paper). -ISBN 0-631-19959-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Philosophy. 2. Criticism. I. Botting, Fred. -

Exposition Permanente.Pdf

CHARLES AND LLLLLMARIE-LAURE DE NOAILLES LLLLA LIFE AS PATRONS PERMANENT EXHIBITION VILLA NOAILLES L/ SAINT BERNARD PRESS KIT Press contact Philippe Boulet +33 (0)6 82 28 00 47 [email protected] Contact villa Noailles +33 (0)4 98 08 01 98 www.villanoailles-hyeres.com Visuels haute définition disponible en téléchargement sur l’espace presse www.villanoailles-hyeres.com (mot de passe sur demande) LLL EDITOrial LLLLLL Despite a reputation whose importance never ceases to Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles grasped that modernity increase, nobody had ever devoted an exhibition to Charles was a combination of numerous influences, a montage of forms, and Marie-Laure de Noailles, the renowned benefactors. Their seemingly unsuited towards coexisting in the same space; as name – which was associated with an impressive list of artists expressed in both the construction of the villa, or its interior and intellectuals – is present in all of the works which discuss design, which in itself arose out of a montage of furnishings that the period. Despite this, no attempt had been made to re- were the product of the most diverse trends. Consequently, they assemble and inventory the countless details and documents freely combined furniture by Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann, Jean- which relate to their involvement. Ever since the inauguration Michel Frank, Charlotte Perriand, and Francis Jourdain, with of the villa Noailles arts centre, the organisation in charge of its industrial fittings, created by Smith & Co and Ronéo, alongside exhibitions had always intended to present this legacy in full view period pieces. of the contemporary exhibitions. At the same time, there was an obligation to introduce people to the history, the architecture, When Charles de Noailles offered his support to the key and the furnishings of the villa Noailles. -

A Thesis Submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts

FROM ANCIENT GREECE TO SURREALISM: THE CHANGING FACES OF THE MINOTAUR A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Brenton Pahl December, 2017 Thesis written by Brenton Pahl B.A., Cleveland State University, 2009 M.A., Kent State University, 2017 Approved by —————————————————— Marie Gasper-Hulvat, Ph.D., Advisor —————————————————— Marie Bukowski, M.F.A., Director, School of Art —————————————————— John Crawford-Spinelli, Ed.D., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF FIGURES ………………………………………………………………………………….……iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ………………………………………………………………………………..vii I. INTRODUCTION Mythology in Surrealism ………………………………………………………………………….1 The Minotaur Myth ………………………………………………………………………………..4 The Minotaur in Art History …………………………………………………..…………………..6 II. CHAPTER 1 Masson’s Entry into Surrealism ……………………..…………………………………..…….…10 The Splintering of Surrealism …………..…………………….…………………………….……13 La Corrida …………………………………………………………………………………….….15 III. CHAPTER 2 The Beginnings of Minotaure ……………………………………………………………………19 The Remaining Editions of Minotaure …………………………………………………………..23 IV. CHAPTER 3 Picasso’s Minotaur ……………………………………………………………..………….……..33 Minotauromachy …………………………………………………………………………………39 V. CHAPTER 4 Masson and the Minotaur …………………..…………………………………………………….42 Acephalé ………………………………………………………………………………………….43 The Return to the Minotaur ………………………………………………………………………46 Masson’s Second Surrealist Period …………………..………………………………………….48 VI. CONCLUSION -

Jeudi 16 Et Vendredi 17 Mai 2013 Paris Drouot

exp er t claude oterelo JEUDI 16 ET VENDREDI 17 MAI 2013 PARIS DROUOT JEUDI 16 MAI 2013 À 14H15 du n°1 au n°294 VENDREDI 17 MAI 2013 À 14H15 du n°296 au n°594 Exposition privée Etude Binoche et Giquello 5 rue La Boétie - 75008 Paris Lundi 13 mai 2013 de 11h à 18h et mardi 14 mai 2013 de 11h à 16h Tél . 01 47 42 78 01 Exposition publique à l’Hôtel Drouot Mercredi 15 mai 2013 de 11h à 18 heures Jeudi 16 et vendredi 17 mai 2013 de 11h à 12 heures Téléphone pendant l’exposition 01 48 00 20 09 PARIS - HÔTEL DROUOT - SALLE 9 COLLECTION D’UN HISTORIEN D’ART EUROPÉEN QUATRIÈME PARTIE ET À DIVERS IMPORTANT ENSEMBLE CONCERNANT VICTOR BRAUNER AVANT-GARDES DU XXE SIÈCLE ÉDITIONS ORIGINALES - LIVRES ILLUSTRÉS - REVUES MANUSCRITS - LETTRES AUTOGRAPHES PHOTOGRAPHIES - DESSINS - TABLEAUX Claude Oterelo Expert Membre de la Chambre Nationale des Experts Spécialisés 5, rue La Boétie - 75008 Paris Tél. : 06 84 36 35 39 [email protected] 5, rue La Boétie - 75008 Paris - tél. 33 (0)1 47 70 48 90 - fax. 33 (0) 1 47 42 87 55 [email protected] - www.binocheetgiquello.com Jean-Claude Binoche - Alexandre Giquello - Commissaires-priseurs judiciaires s.v.v. agrément n°2002 389 Commissaire-priseur habilité pour la vente : Alexandre Giquello Les lots 9 à 11 sont présentés par Antoine ROMAND - Tel. 06 07 14 40 49 - [email protected] 4 Jeudi 16 mai 2013 14h15 1. ARAGON Louis. TRAITÉ DU STYLE. Paris, Editions de la N.R.F., 1928. -

Ecrire La Sculpture Dans ''Documents'

Ecrire la sculpture dans ”Documents”, magazine illustré (1929-1930) Françoise Levaillant To cite this version: Françoise Levaillant. Ecrire la sculpture dans ”Documents”, magazine illustré (1929-1930). Ecrire la sculpture (XIXe-XXe siècle), Jun 2011, Paris, France. halshs-00692176 HAL Id: halshs-00692176 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00692176 Submitted on 28 Apr 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Centre national de la recherche scientifique Centre André Chastel 2011 Ecrire la sculpture dans ‘Documents’, magazine illustré (1929‐1930) Françoise Levaillant 1 Écrire la sculpture dans Documents, magazine illustré (1929-1930) Pour Fumio Chiba « Écrire la sculpture » : à ce défi d’actualité lancé à l’historien de l’art, de réfléchir sur les modalités des « commentaires sur » la sculpture, en supposant que, dans l’histoire récente, il apparaît plus fréquent qu’un écrivain, un poète, un critique commente la « toile peinte » que le volume, comment répondre ? Écrire la sculpture n’est pas seulement un commentaire, c’est un acte d’inscription par le langage. Écrire la sculpture, c’est, au sens où l’entendait Callistrate1, créer, par l’écriture, des équivalents de sculpture, des simulacres langagiers qui la font, paradoxalement, « revivre », « s’animer », qui, de tout temps, permettent d’en mémoriser telle partie, telle forme, tel effet comme en un carnet de voyage avec ou sans croquis, avec ou sans photographie. -

André Breton Ve Sürrealist Resim Ilişkisi Ayşe Güngör

ANDRÉ BRETON VE SÜRREALİST RESİM İLİŞKİSİ AYŞE GÜNGÖR IŞIK ÜNİVERSİTESİ 2011 ANDRÉ BRETON VE SÜRREAL İST RES İM İLİŞ KİSİ AY ŞE GÜNGÖR İstanbul Üniversitesi, Edebiyat Fakültesi, Antropoloji Bölümü, 2009 Bu Tez, I şık Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü’ne Yüksek Lisans (MA) derecesi için sunulmu ştur. IŞIK ÜN İVERSITES İ 2011 ANDRÉ BRETON VE SÜRREAL İST RES İM İLİŞ KİSİ Özet Bu tezin temel amacı, sürrealizmin kurucusu olan André Breton ve sürrealist resim arasındaki ili şkiyi ortaya koymaktır. Bu tezde öncelikle sürrealizmin tarihsel arkaplanı sunulmu ştur. Sonraki bölüm André Breton’un hayatı hakkında kronolojik bilgilerle okuyanlara bilgi vermektedir. Son olarak, André Breton’un yazmı ş oldu ğu makaleler, kitaplara odaklanarak, Breton’un bir sanatsever, bir entelektüel ve bir sanat teorisyeni olarak sunulması amaçlanmı ştır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Sürrealizm, Resim, Sürrealist Sanat, André Breton, Sürrealizm ve Resim, 20. yüzyıl Sanatı i THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ANDRÉ BRETON AND SURREALIST PAINTING Abstract The main aim of this thesis is to clarify the relationship between André Breton, the founder of surrealism and the surrealist painting. First of all, in this thesis, surrealism’s historical background have been presented. The next part have designed to acquaint the readers about André Breton’s life with chronological information. In conclusion, by focusing Breton’s articles and books about surrealist art, to represent André Breton as an art-lover, intellectual and art theorist have been aimed. Keywords: Surrealism, Painting, Surrealist Art, André Breton, Surrealism and Painting, 20th Century Art ii Te şekkür Işık Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Sanat Kuramı ve Ele ştiri Programıyla, ülkemizde bir ilki gerçekle ştiren ve bu alanda kuramsal bilginin aktarılmasının yolunu açan Sayın Prof. -

Download the Text About the Exhibition

Shana Lutker Paul, the Peacock, the Raven and the Dove Wetterling Gallery, Stockholm October 9-31, 2015 Open letter to Paul Claudel, Ambassador of FRANCE to JAPAN "As for the current movements, not one can not lead to a genuine renewal or creation. Neither Dadaism nor Surrealism—they have only one meaning: pederasty. More than one is surprised not that I am a good Catholic, but also writer, diplomat, ambassador of France and poet. But I do not find in all this anything strange. During the war, I went to South America to buy food, canned meat, lard for the armies, and I made my country two hundred million.” —"Il Secolo" Interview with Paul Claudel, Comoedia, June 17, 1925. Dear M. Claudel, Our activity is only pederastic as it introduces confusion in the minds of those who do not take part in it. Creation matters little to us. We profoundly hope that revolutions, wars, and colonial insurrections will annihilate this Western civilization whose vermin you defend even in the Orient. There can be to us neither balance nor great art. Here, already, for a long time: the idea of Beauty has been stale. It remains standing only as a moral idea, for example, the fact that one can be both poet and Ambassador to France. We assert that we find treason and all that can harm the security of the State one way or another much more reconcilable with Poetry than your sale of “great quantities of lard” on behalf of a nation of pigs and dogs. It is a singular lack of awareness of the possibilities and faculties of the mind that periodically seek their salvation with scoundrels of your species in the Catholic and Greco-Roman tradition.