On Being a Black Canadian Writer Creating Through Community The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M. Nourbese Philip's Bibliography

Tables of Contents M. NOURBESE PHILIP’S BIBLIOGRAPHY PAGE POETRY Books 1 Anthologies 1 Magazines & Journals 3 PROSE: LONG FICTION Books 5 Anthologies (excerpts) 5 Magazines and Journals (excerpts) 5 PROSE: SHORT FICTION Anthologies 6 Magazines and Journals 6 PROSE: NON-FICTION Books Appearances 8 Anthologies 8 Magazines, Journals, Newspapers and 9 Catalogues DRAMA 12 INTERVIEWS 13 RADIO AND TELEVISION On-Air Appearances 14 On-Air Readings 15 Documentaries 15 CONFERENCES 16 READINGS AND TALKS 19 KEYNOTE LECTURES AND SPEECHES 26 RESIDENCIES 28 P o e t r y | 1 POETRY BOOKS Zong!, Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT, 2008. Zong!, (Spanish Bilingual edition) She Tries Her Tongue; Her Silence Softly Breaks, Poui Publications, Toronto, 2006. She Tries Her Tongue; Her Silence Softly Breaks, The Women's Press, London, 1993. She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks, Ragweed Press, Charlottetown, 1988. She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks, Casa de las Americas, Havana, 1988. Salmon Courage, Williams Wallace Inc., Stratford, 1983. Thorns, Williams Wallace Inc., Stratford, 1980. ANTHOLOGIES Best American Experimental Writing 2014, ed. Cole Swensen, Omnidawn Publishing, Richmond, 2014. Eleven More American Women Poets in the 21st Century, eds. Claudia Rankine, and Lisa Sewell, Wesleyan University Press, Middleton, 2012. “Questions! Questions!” Rotten English, ed. Dora Ahmad, WW Norton & Co., New York, 2007. “Salmon Courage,” “Meditations on the Declension of Beauty by the Girl with the Flying Cheekbones,” ‘The Catechist,” and “Cashew #4," Revival - An Anthology of Black Canadian Writing, ed. Donna Bailey Nurse, McClelland & Stewart, Toronto, 2006. “Discourse on the Logic of Language”, Introduction to Literature, Harcourt, Toronto, 2000. -

Island Ecologies and Caribbean Literatures1

ISLAND ECOLOGIES AND CARIBBEAN LITERATURES1 ELIZABETH DELOUGHREY Department of English, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 2003 ABSTRACT This paper examines the ways in which European colonialism positioned tropical island landscapes outside the trajectories of modernity and history by segregating nature from culture, and it explores how contemporary Caribbean authors have complicated this opposition. By tracing the ways in which island colonisation transplanted and hybridised both peoples and plants, I demonstrate how mainstream scholarship in disciplines as diverse as biogeography, anthropology, history, and literature have neglected to engage with the deep history of island landscapes. I draw upon the literary works of Caribbean writers such as Édouard Glissant, Wilson Harris, Jamaica Kincaid and Olive Senior to explore the relationship between landscape and power. Key words: Islands, literature, Caribbean, ecology, colonialism, environment THE LANGUAGE OF LANDSCAPE the relationship between colonisation and ecology is rendered most visible in island spaces. Perhaps there is no other region in the world This has much to do with the ways in which that has been more radically altered in terms European colonialism travelled from one island of flora and fauna than the Caribbean islands. group to the next. Tracing this movement across Although Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles the Atlantic from the Canaries and Azores to Darwin had been the first to suggest that islands the Caribbean, we see that these archipelagoes are particularly susceptible to biotic arrivants, became the first spaces of colonial experimen- and David Quammen’s more recent The Song tation in terms of sugar production, deforestation, of the Dodo has popularised island ecology, other the importation of indentured and enslaved scholars have made more significant connec- labour, and the establishment of the plantoc- tions between European colonisation and racy system. -

Print Politics: Conflict and Community-Building at Toronto's Women's Press

PRINT POLITICS: CONFLICT AND COMMUNITY-BUILDING AT TORONTO'S WOMEN'S PRESS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Guelph by THABA NI EDZWIECKI In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September, 1997 O Thaba Niedzwiecki, 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale I*m of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie SeMces services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaON K1AON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othemise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT PRlNT POLITICS: CONFLICT AND COMMUNITY-BUILDING AT TORONTO'S WOMEN'S PRESS Thaba Niedzwiecki Advisor: University of Guelph, 1997 Professor Christine Bold This thesis is an investigation into the intersection of print and politics at Toronto's Women's Press, which was the first women-nin feminist publishing house in Canada when founded in 1972. -

Gender, Ethnicity and Literary Represenation

• 96 • Feminist Africa 7 Fashioning women for a brave new world: gender, ethnicity and literary representation Paula Morgan This essay adds to the ongoing dialogue on the literary representation of Caribbean women. It grapples with a range of issues: how has iconic literary representation of the Caribbean woman altered from the inception of Caribbean women’s writing to the present? Given that literary representation was a tool for inscribing otherness and a counter-discursive device for recuperating the self from the imprisoning gaze, how do the politics of identity, ethnicity and representation play out over time? How does representation shift when one considers the gender and ethnicity of the protagonist in relation to that of the writer? Can we assume that self-representation is necessarily the most “authentic”? And how has the configuration of the representative West Indian writer changed since the 1970s to the present? The problematics of literary representation have been with us since Plato and Aristotle wrestled with the purpose of fiction and the role of the artist in the ideal republic. Its problematics were foregrounded in feminist dialogues on the power of the male gaze to objectify and subordinate women. These problematics were also central to so-called third-world and post-colonial critics concerned with the correlation between imperialism and the projection/ internalisation of the gaze which represented the subaltern as sub-human. Representation has always been a pivotal issue in female-authored Caribbean literature, with its nagging preoccupation with identity formation, which must be read through myriad shifting filters of gender and ethnicity. Under any circumstance, representation remains a vexing theoretical issue. -

Autumn 2003 JSSE Twentieth Anniversary

Journal of the Short Story in English Les Cahiers de la nouvelle 41 | Autumn 2003 JSSE twentieth anniversary Olive Senior - b. 1941 Dominique Dubois and Jeanne Devoize Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/337 ISSN: 1969-6108 Publisher Presses universitaires de Rennes Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2003 Number of pages: 287-298 ISSN: 0294-04442 Electronic reference Dominique Dubois and Jeanne Devoize, « Olive Senior - b. 1941 », Journal of the Short Story in English [Online], 41 | Autumn 2003, Online since 31 July 2008, connection on 03 December 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/jsse/337 This text was automatically generated on 3 December 2020. © All rights reserved Olive Senior - b. 1941 1 Olive Senior - b. 1941 Dominique Dubois and Jeanne Devoize EDITOR'S NOTE Interviewed by Dominique Dubois, and Jeanne Devoize., Caribbean Short Story Conference, January 19, 1996.First published in JSSE n°26, 1996. Dominique DUBOIS: Would you regard yourself as a feminist writer? Olive SENIOR: When I started to write, I wasn't conscious about feminism and those issues. I think basically my writing reflects my society and how it functions. Obviously, one of my concerns is gender. I tend to avoid labels. Jeanne DEVOIZE: How can you explain that there are so many women writers in Jamaica, particularly as far as the short story is concerned. O.S.: I think there are a number of reasons. One is that it reflects what happened historically in terms of education: that a lot more women were, at a particular point in time, being educated through high school, through university and so on. -

Winnipeg Yiddish Women's Reading Circle

UNESCO REGISTER OF GOOD PRACTICES IN LANGUAGE PRESERVATION Winnipeg Yiddish Women’s Reading Circle (Canada) Received: spring 2006; last updated: summer 2008 Brief description: This report describes the activities of the Winnipeg Yiddish Women’s Reading Circle, a reading group in Manitoba, Canada that uses texts in Yiddish to provide participants with opportunities to speak and read the language, to regain confidence in their linguistic competence and to tutor each other . Yiddish is a Germanic Jewish language. In the 2006 census of Canada, 16,295 people indicated Yiddish as their mother tongue. For the Winnipeg (Manitoba) community, where the project is located, the number of Yiddish speakers is approximately six hundred. The Reading Circle was started in the wake of the rediscovery of Yiddish women's literature at a local library event in Winnipeg. In the circle, female members of the local Yiddish community meet regularly once a month to read and discuss texts by female Yiddish authors. Since the start of this library event, the Reading Circle activities have resulted in the revitalization of Yiddish language competence in its members. Reading the texts aloud and group discussion on the texts as well as language issues more generally, has allowed for an invigorating exchange between more and less fluent Yiddish speakers. As a further result, an anthology of English translations of stories by the female Yiddish authors, edited by an academic expert, was published. The Reading Circle assisted with the translation and compilation of texts for this anthology, further contributing to the rediscovery and revitalization of Yiddish among participants. UNESCO REGISTER OF GOOD PRACTICES IN LANGUAGE PRESERVATION Reader’s guide: This project is an example of a community-driven, low-cost effort for language revitalization via the social activity of regularly holding a reading circle, using texts in the endangered language of Yiddish. -

Jamaican Women Poets and Writers' Approaches to Spirituality and God By

RE-CONNECTING THE SPIRIT: Jamaican Women Poets and Writers' Approaches to Spirituality and God by SARAH ELIZABETH MARY COOPER A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Centre of West African Studies School of Historical Studies The University of Birmingham October 2004 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Chapter One asks whether Christianity and religion have been re-defined in the Jamaican context. The definitions of spirituality and mysticism, particularly as defined by Lartey are given and reasons for using these definitions. Chapter Two examines history and the Caribbean religious experience. It analyses theory and reflects on the Caribbean difference. The role that literary forefathers and foremothers have played in defining the writers about whom my research is concerned is examined in Chapter Three, as are some of their selected works. Chapter Four reflects on the work of Lorna Goodison, asks how she has defined God whether within a Christian or African framework. In contrast Olive Senior appears to view Christianity as oppressive and this is examined in Chapter Five. -

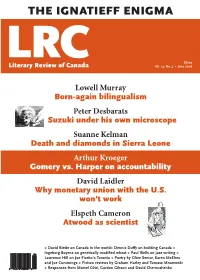

The Ignatieff Enigma

THE IGNATIEFF ENIGMA $6.00 LRCLiterary Review of Canada Vol. 14, No. 5 • June 2006 Lowell Murray Born-again bilingualism Peter Desbarats Suzuki under his own microscope Suanne Kelman Death and diamonds in Sierra Leone Arthur Kroeger Gomery vs. Harper on accountability David Laidler Why monetary union with the U.S. won’t work Elspeth Cameron Atwood as scientist + David Biette on Canada in the world+ Dennis Duffy on building Canada + Ingeborg Boyens on genetically modified wheat + Paul Wells on jazz writing + Lawrence Hill on Joe Fiorito’s Toronto + Poetry by Olive Senior, Karen McElrea and Joe Cummings + Fiction reviews by Graham Harley and Tomasz Mrozewski + Responses from Marcel Côté, Gordon Gibson and David Chernushenko ADDRESS Literary Review of Canada 581 Markham Street, Suite 3A Toronto, Ontario m6g 2l7 e-mail: [email protected] LRCLiterary Review of Canada reviewcanada.ca T: 416 531-1483 Vol. 14, No. 5 • June 2006 F: 416 531-1612 EDITOR Bronwyn Drainie 3 Beyond Shame and Outrage 18 Astronomical Talent [email protected] An essay A review of Fabrizio’s Return, by Mark Frutkin ASSISTANT EDITOR Timothy Brennan Graham Harley Alastair Cheng 6 Death and Diamonds 19 A Dystopic Debut CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Anthony Westell A review of A Dirty War in West Africa: The RUF and A review of Zed, by Elizabeth McClung the Destruction of Sierra Leone, by Lansana Gberie Tomasz Mrozewski ASSOCIATE EDITOR Robin Roger Suanne Kelman 20 Scientist, Activist or TV Star? POETRY EDITOR 8 Making Connections A review of David Suzuki: The Autobiography Molly -

The Engagement Between Past and Present in African American And

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy The Engagement between Past and Present in African American and Caribbean Literature: Orality in the Fiction of Toni Morrison, Gayl Jones, Edwidge Danticat, and Olive Senior by Jacoba Bruneel Paper submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- Prof. Ilka Saal en Letterkunde: Engels” May, 2010 The Engagement between Past and Present in African American and Caribbean Literature: Orality in the Fiction of Toni Morrison, Gayl Jones, Edwidge Danticat, and Olive Senior by Jacoba Bruneel Prof. Ilka Saal Ghent University Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Ilka Saal, for her advice and guidance which helped me to gain new insights into my topic, and for her enthusiasm which encouraged me to delve deeper. Special thanks to Dr. James Procter of the University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, whose fascinating lectures on the Caribbean short story sparked my interest in the literature of the Caribbean, and to Prof. Susan Griffin who stimulated my interest in scholarly research in her “Scenes of Reading” seminars. I would also like to thank my family for their warm support and encouragements, and my friends for standing by me during these stressful times and for being there when I most needed them. Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 1. Similarities in the Use of Orality in African American and Caribbean Fiction ............. 10 1.1. Vernacular in Dialogue and Narrative .................................................................... 11 1.2. Written Performance ............................................................................................... 16 1.3. Call-and-Response: Seeking Engagement .............................................................. 20 1.4. Orality and the Written Text: a Fertile Hybridity .................................................. -

Annual Report 2009-2010 Institute for the Humanities Annual Report 2009-2010

University of manitoba institute for the humanities annual report 2009-2010 institute for the humanities annual report 2009-2010 index Introduction 1 message from the director 1 Publications by the Director 2 Including Director’s 2009-10 Research umih research initiative 2 LGBTTQ Archival & Oral History Initiative the research affiliates 4 Including 2009-10 Affiliate Publications the research clusters 5 Law & Society 5 Power & Resistance in Latin America 5 Jewish Studies Research Circle 7 UMIH on-campus programming 7 UMIH off-campus programming 9 Co-Sponsorships with Other Units 9 graduate student training & outreach 9 Graduate Student Public Talks 10 financial report 2009-10 10 2010-11 Asking Budget 11 Board of Management 11 institute for the humanities 12 UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA INSTITUTE FOR THE HUMANITIES ANNUAL REPORT 2009-2010 Introduction Throughout the year, the UMIH, with support from the Faculty of Arts, held a number of sessions for new scholars that attempted The constitution of the Institute requires the Director to report to provide an informal space to discuss the challenges of being a annually to the Dean of Arts, the Vice-President (Academic) and new faculty member. These sessions, normally held over lunchtime, Provost, and the Vice-President (Research). It is customary for ranged from discussing teaching and University service, to research this report to be presented annually at the year-end meeting of the potential and possibilities, as well as sources of intellectual and Board of Management. Copies are also distributed on campus to collegial support. We intend to continue this series next year and the President, the Associate Deans of Arts, the Institute’s Board of to reach out to new Faculty who are looking for potential linkages Management, and many supporters who are members of the Uni- for interdisciplinary collaboration. -

The Anne Szumigalski Collection

The Anne Szumigalski Collection. Anne Szumigalski A Finding Aid of the Anne Szumigalski at the University of Saskatchewan Prepared by Craig Harkema **(finished by Joel Salt) Special Collections Librarian Research Services Division University of Saskatchewan Library Fall 2009 Collection Summary Title: Papers of Anne Szumigalski Dates: 1976-2008. ID No.: Szumigalski Collection: MSS 61 – Creator: Szumigalski – 1922-1999; Extent: 3 boxes; 46cm; Language: Collection material in English Repository: Special Collections, University of Saskatchewan. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Biographical Note: Anne Szumigalski, poet (b at London, Eng 3 Jan 1922; d at Saskatoon 22 Apr 1999). Raised in rural Hampshire, she served as an interpreter with the Red Cross during World War II, and in 1951 immigrated with her husband and family to Canada. A translator, editor, playwright, teacher and poet, she was instrumental in founding the Saskatchewan Writers' Guild and the literary magazine Grain. She wrote or co-wrote 14 books, mostly poetry, including Woman Reading in a Bath (1974) and A Game of Angels (1980). Her poetry explores the world of the imagination, a fantastic landscape that stretches between and beyond birth and death and is characterized by the simultaneous concreteness and illogic nature of dreams. She also explores the formal possibilities of the prose poem in several volumes, including Doctrine of Signatures (1983), Instar (1985) and Rapture of the Deep (1991). Because of its appearance on the page, the prose poem is freed from some of the conventions and expectations of the lyric poem, lending itself well to the dreamlike juxtapositions and leaps central to Szumigalski's work. She also wrote her autobiography, The Voice, the Word, the Text (1990) and a play about the Holocaust, Z. -

Book Reviews -Gesa Mackenthun, Stephen Greenblatt, Marvelous Possessions: the Wonder of the New World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991

Book Reviews -Gesa Mackenthun, Stephen Greenblatt, Marvelous Possessions: The wonder of the New World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991. ix + 202 pp. -Peter Redfield, Peter Hulme ,Wild majesty: Encounters with Caribs from Columbus to the present day. An Anthology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. x + 369 pp., Neil L. Whitehead (eds) -Michel R. Doortmont, Philip D. Curtin, The rise and fall of the plantation complex: Essays in Atlantic history. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990. xi + 222 pp. -Roderick A. McDonald, Hilary McD.Beckles, A history of Barbados: From Amerindian settlement to nation-state. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. xv + 224 pp. -Gertrude J. Fraser, Hilary McD.Beckles, Natural rebels; A social history of enslaved black women in Barbados. New Brunswick NJ and London: Rutgers University Press and Zed Books, 1990 and 1989. ix + 197 pp. -Bridget Brereton, Thomas C. Holt, The problem of freedom: Race, labor, and politics in Jamaica and Britain, 1832-1938. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1991. xxxi + 517 pp. -Peter C. Emmer, A. Meredith John, The plantation slaves of Trinidad, 1783-1816: A mathematical and demographic inquiry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. xvi + 259 pp. -Richard Price, Robert Cohen, Jews in another environment: Surinam in the second half of the eighteenth century. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1991. xv + 350 pp. -Russell R. Menard, Nigel Tattersfield, The forgotten trade: comprising the log of the Daniel and Henry of 1700 and accounts of the slave trade from the minor ports of England, 1698-1725. London: Jonathan Cape, 1991. ixx + 460 pp. -John D. Garrigus, James E.