30877 Notre Dame

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Indigenous Petitions

Australian Indigenous Petitions: Emergence and Negotiations of Indigenous Authorship and Writings Chiara Gamboz Dissertation Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences October 2012 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT 'l hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the proiect's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.' Signed 5 o/z COPYRIGHT STATEMENT 'l hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or digsertation in whole or part in the Univercity libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertiation. -

Australia's Carceral Islands in the Colonial Period, 1788–1901

IRSH 63 (2018), Special Issue, pp. 45–63 doi:10.1017/S0020859018000214 © 2018 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis A Natural Hulk: Australia’s Carceral Islands in the Colonial Period, 1788–1901* K ATHERINE R OSCOE Institute of Historical Research, University of London Senate House, Malet Street, London, WC1E 7HU, UK E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: During the British colonial period, at least eleven islands off the coast of Australia were used as sites of “punitive relocation” for transported European convicts and Indigenous Australians. This article traces the networks of correspondence between the officials and the Colonial Office in London as they debated the merits of various offshore islands to incarcerate different populations. It identifies three roles that carceral islands served for colonial governance and economic expansion. First, the use of con- victs as colonizers of strategic islands for territorial and commercial expansion. Second, to punish transported convicts found guilty of “misconduct” to maintain order in colonial society. Third, to expel Indigenous Australians who resisted colonization from their homeland. It explores how, as “colonial peripheries”, islands were part of a colo- nial system of punishment based around mobility and distance, which mirrored in microcosm convict flows between the metropole and the Australian colonies. ISLAND INCARCERATION Today, the island continent of Australia has more than 8,000 smaller islands off its coast.1 As temperatures rose 6,000 years ago, parts of the -

Street Names Index

City of Fremantle and Town of East Fremantle Street Names Index For more information please visit the Fremantle City Library History Centre Place Name Suburb Named After See Also Notes Ada Street South Fremantle Adams Street O'Connor The Adcock brothers lived on Solomon Street, Fremantle. They were both privates in the 11 th Frank Henry Burton Adcock ( - Battalion of the AIF during WWI. Frank and Adcock Way Fremantle 1915) and Fredrick Brenchley Frederick were both killed in action at the Adcock ( - 1915) landing at Gallipoli on the 25 th of April 1915, aged 21 and 24 years. Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, queen Adelaide Street Fremantle consort of King William IV (1830- Appears in the survey of 1833. 1837). Agnes Street Fremantle Ainslie Road North Fremantle Alcester Road East Fremantle Alcester, England Alexander was Mayor of the Municipality of Wray Avenue Fremantle, 1901-02. Alexander Road Fremantle Lawrence Alexander and Hampton Originally Hampton Street until 1901-02, then Street named Alexander Road, and renamed Wray Avenue in 1923 after W.E. Wray. Alexandra of Denmark, queen Queen Alexandra was very popular throughout Alexandra Road East Fremantle consort of King Edward VII (1901- her time as queen consort and then queen 1910). mother. 1 © Fremantle City Library History Centre Pearse was one of the original land owners in Alice Avenue South Fremantle Alice Pearse that street. This street no longer exists; it previously ran north from Island Road. Alfred Road North Fremantle Allen was a civil engineer, architect, and politician. He served on the East Fremantle Municipal Council, 1903–1914 and 1915–1933, Allen Street East Fremantle Joseph Francis Allen (1869 – 1933) and was Mayor, 1909–1914 and 1931–1933. -

An Ethnohistorical Study of the Swan-Canning Fishery in Western Australia, 1697-1837

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 1991 An ethnohistorical study of the Swan-Canning Fishery in Western Australia, 1697-1837 Paul R. Weaver Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Australian Studies Commons, Demography, Population, and Ecology Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Weaver, P. R. (1991). An ethnohistorical study of the Swan-Canning Fishery in Western Australia, 1697-1837. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/248 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/248 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

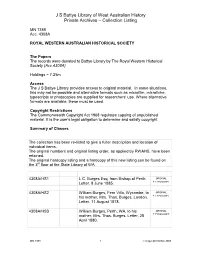

JS Battye Library of West Australian History Private Archives

J S Battye Library of West Australian History Private Archives – Collection Listing MN 1388 Acc. 4308A ROYAL WESTERN AUSTRALIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY The Papers The records were donated to Battye Library by The Royal Western Historical Society (Acc.4308A) Holdings = 7.25m Access The J S Battye Library provides access to original material. In some situations, this may not be possible and alternative formats such as microfilm, microfiche, typescripts or photocopies are supplied for researchers’ use. Where alternative formats are available, these must be used. Copyright Restrictions The Commonwealth Copyright Act 1968 regulates copying of unpublished material. It is the user’s legal obligation to determine and satisfy copyright. Summary of Classes The collection has been re-listed to give a fuller description and location of individual items. The original numbers and original listing order, as applied by RWAHS, have been retained. The original hardcopy listing and a hardcopy of this new listing can be found on the 3rd floor at the State Library of WA 4308A/HS1 L.C. Burges Esq. from Bishop of Perth. ORIGINAL Letter, 8 June 1885. + TYPESCRIPT 4308A/HS2 William Burges, Fern Villa, Wycombe, to ORIGINAL his mother, Mrs. Thos. Burges, London. + TYPESCRIPT Letter, 11 August 1878. 4308A/HS3 William Burges, Perth, WA, to his ORIGINAL mother, Mrs. Thos. Burges. Letter, 28 + TYPESCRIPT April 1880. MN 1388 1 Copyright SLWA 2008 J S Battye Library of West Australian History Private Archives – Collection Listing 4308A/HS4 Tom (Burges) from Wm. Burges, ORIGINAL Liverpool, before sailing for Buenos + TYPESCRIPT Ayres. Letter, 9 June 1865. 4308A/HS5 Richard Burges, Esq. -

In 1988, the People of Western Australia (W

SECOND READING Parliamentary Government in Western Australia (Third revised Internet Edition) Harry CJ Phillips Original Edition Copyright © 1991, Ministry of Education, Western Australia . Reproduction of this work in whole or part for educational purposes within an educational institution in Western Australia and on condition that it not be offered for sale, is permitted by the Ministry of Education. Designed and illustrated by Rod Lewis and computer typeset by West Ed Media, Ministry of Education. Printed by State Print, Department of State Services. ISBN 0 7309 4532 4 ISBN 0 7309 4127 2 (loose-leaf) Internet Edition First published 2003 by Parliament of Western Australia, Parliament House, Perth, Western Australia Revised Internet Edition © Western Australia, 2014 Reproduction of this work in whole or part for educational purposes within an educational institution in Western Australia and on condition that it not be offered for sale, is permitted by the Parliament of Western Australia. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface (i) Acknowledgements (ii) 1. Citizens of Western Australia: Government and Politics 1 Chapter 1 - Terms 7 2. Australia’s Federal System 8 Chapter 2 - Terms 21 3. Parliament’s History in Western Australia 22 Chapter 3 - Terms 32 4. The Western Australian Constitutional Framework 33 Chapter 4 - Terms 44 5. How a Law is Made in Western Australia 45 Chapter 5 - Terms 58 6. People in Western Australia’s Parliament 59 Chapter 6 - Terms 66 7. Parliament at Work 67 Chapter 7 - Terms 79 8. Parliament House 80 Chapter 8 - Terms 92 9. Elections and Referendums 93 Chapter 9 - Terms 109 10. Political Parties and Party Leaders 110 Chapter 10 - Terms 119 11. -

Our Western Land 1829 – 1890

Our Western Land Foundation Day 1 June 1829 to Proclamation Day 21 October 1890 This is the first of four historical facts sheets prepared for Celebrate WA by Ruth Marchant James. The purpose of these documents is to present a brief and accurate timeline of the important dates and events in the history of Western Australia. Pre-European Settlement 1696/ 1697 A Dutch expedition led by Willem de Vlamingh in The Aboriginal people have inhabited the continent command of the Geelvinck, accompanied by the of Australia for over 40,000 years. Among the many NiJptangh and Weseltje reached and named tribes representing various districts in Western Rottnest on 29 December 1696. On 5 January Australia are: 1697, before sailing north, a party explored the mainland from Cottesloe to the Swan River which Nyungar (South-West) De Vlamingh named after the black swans he Yamatji (Murchison) discovered. Bardi (Broome) 1699 In command of the Roebuck, Dampier made a Ngaamyatjarra (Warburton Ranges) second visit. He landed at Shark’s Bay and Walmadjeri (Fitzroy district) Dampier Archipelago. Indjibandji (Pilbara) 1712 Wreck of the Zuyrdorp on the north of the Exploration, Murchison River. 1791 Capt George Vancouver in Discovery named King Pre-European George Sound (Albany). Settlement 1792 A French survey of the south coast involved two vessels, Recherche under the command of 1616 Dirk Hartog in Eendracht discovered Dirk Captain D’Entrecasteaux, and Esperance under Hartog Island while visiting the Shark Bay Captain de Kermadec area. 1801 Capt Matthew Flinders, in command of Investigator, visited King George Sound. 1801 – 1618 Van Hillcom, on board Zeewulfe sighted the 1803, two French scientific expeditions involving same section of the northern coast three ships Geographe, Naturaliste and 1619 Frederick de Houtman in command of the Casuarina, commanded respectively by Cmdr Dordrecht discovered and named Houtman Nicolas Baudin, Capt. -

Learning Sequence 1, Teacher Resource 1 the Swan River Colony 1829 - 1846 Perth in 1845

Learning Sequence 1, Teacher Resource 1 The Swan River Colony 1829 - 1846 Perth in 1845 This map of Perth in 1845 and activities includes an introductory lesson to stimulate student curiosity and questions about early Perth. It can also be used in conjunction with information in Teacher Resource 2: Features of Colonial Society 1829 to 1850. Teacher Resources 1 and 2 aim to develop an understanding of the physical, social, economic and political context for the study of the Sisters of Mercy, who arrived in the Swan River Colony in January 1846. Source: Western Australian State Records Office An online version of this map, which can be enlarged to view Perth streets in more detail, can be accessed through the State Records Office. To access the map you click on Perth Townsite 1845 - Datasets - data.wa.gov.au and then on the live link next to "Data portal". The map can be enlarged by using the cursor. Use this map on a Smart Board or project it onto a screen to encourage student discussion which will check prior knowledge of Perth. Students can conduct a "Think, Pair, Share" activity to initiate questions. You might like to suggest some themes such as: 1. The origin of Perth's street names or any changes to street names. 2. The swamps in the city area - what has happened to them? 3. Location of current landmarks such as: • The WACA Grounds (Perth Meadows) • Government House 1 • Stirling Square and the Old Court House • East Perth Cemeteries • The jetties (at Mill and William Streets) For more information on the jetties see: http://cms.slwa.wa.gov.au/swan_river/shaping_perth_water/the_causeway • The location of the Causeway • The Town Hall (not built until 1870) • St Georges Cathedral • Victoria Square - St Mary's Cathedral (and Mercy Heritage Centre). -

From the Ground

BE PART OF A POWERFUL AND UNFORGETTABLE MUSICAL EXPERIENCE AT EAST PERTH CEMETERIES SOUND FROM THE GROUND PROGRAM FRIDAY 29 APRIL & SATURDAY 30 APRIL 2016 Government of Western Australia Department of Culture and the Arts EAST PERTH SOUND FROM THE GROUND: CEMETERIES HISTORY PROJECT BACKGROUND From tuberculosis, brought to the colony from St Bartholomew’s, consecrated in 1871 as a Church of The collection of graves at East Perth Cemeteries From its initial conception, Sound from the Ground has the Old World, to typhoid, a fever that struck England mortuary chapel, became a Parish Church from represents a cross section of Perth society from 1829 been underpinned by a number of aims that include Perth at the same time as gold fever, the graves 1888 and after extensions in 1900 it almost doubled in size. to 1899 in a setting that provides a rare experience of enhancing awareness and understanding of the collection of East Perth Cemeteries are a record of the first It remains a consecrated church still in use today. Other isolation and tranquillity in the midst of a busy city. of graves, to ensure its relevance to contemporary society 70 years of European migration. denominations used their own church or place of worship It is an extremely significant collection generally and to introduce some of the stories the collection for the ‘celebration of death’ prior to the cemetery burial. considered by few other than genealogical researchers. represents to new audiences. In addition the project The first burial ground on what was called “Cemetery Hill” has challenged notions of how heritage collections was a general cemetery. -

James Backhouse Correspondence

BACKHOUSE RS.58 Presented to the Royal Society of Tasmania by A.J. Crosfield, 1933. JAMES BACKHOUSE CORRESPONDENCE 1831 - 1838 James Backhouse (1794-1869) was a Quaker missionary, of Darlington, and later, York, England. In 1831 he sailed for Australia, accompanied by George Washington Walker (1800-1859), with the financial support of the London Yearly Meeting. They arrived in Hobart in February 1832 and from then until their departure from Australia in 1838 they visited most of the scattered settlements throughout Australia. They spent three years in Van Diemens Land where they visited the penal settlements, reported to Lieut.-Governor Arthur on conditions and made suggestions for improvement of the prisons, chain gangs, assigned servants etc. They also encouraged the formation of benevolent services, such as the Ladies Committees for visiting prisoners on Elizabeth Fry's model, inspected hospitals and recommended humane treatment for the insane, as well as distributing religious tracts and school books. In 1833 they established a Monthly Meeting of the Society of Friends in Hobart and in 1834 the Hobart Yearly Meeting. In 1837 they bought property for a Meeting House in Hobart. James Backhouse also collected many botanical specimens and continued to correspond with the Tasmanian Society and the Royal Society. After his return to England, Backhouse published an account of his journeys as A Narrative of a Visit to the Australian Colonies (London, 1843) (See Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol. 1.) The correspondence consists of letters addressed to James Backhouse and his companion relating to their missionary journey. Most are from people in official positions thanking the missionaries for their work, acknowledging books and reports, replying to requests for information or offering int~oductions, help and hospitality and also some discussion of religious matters and references to botany in which J.B. -

Membership of the Legislative Council 1832–1870

MEMBERSHIP OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL 1832–1870. Between 1832 and 1867 the membership of the Legislative Council consisted of the Governor and four (five from 1847) official nominee members who were also members of the Executive Council. From 1839 there were also four non-official nominee members, increasing to six in 1867. The lists that follow do not take account of a number of short-term official nominee members in an acting capacity. GOVERNOR Captain James Stirling, 1832–1839 Administrator/Lt Gov Frederick Chidley Irwin, 1832–1833 (Sep) Administrator/Lt Gov Captain Richard Daniell, 1833 (Sep)–1834 (Aug) John Hutt, 1839–1846 Lt Col Andrew KH Clarke, 1846–1847 Administrator Lt Col Frederick Chidley Irwin, 1847–1848 Captain Charles Fitzgerald, 1848–1855 Arthur Edward Kennedy, 1855–1862 John Stephen Hampton, 1862–1868 Administrator Lt Col John Bruce, 1869–1870 Frederick Aloysius Weld, 1870–1875 OFFICIAL NOMINEE MEMBERS Commandant (Commander of the Troops/most senior officer) Captain Frederick Chidley Irwin, 1832–1833 (Sep) Captain Richard Daniell, 1833–1835 (July) (deceased) Captain (later Lt Col) Frederick Chidley Irwin, 1836–1854 Lt Col GM Reeves, 1854–1855 Lt Col John Bruce, 1855–1870 Major Robert Henry Crampton (Acting), 1867 Colonial Secretary Peter Broun (Brown), 1832–1846 George Fletcher Moore (Acting), 1846 (Nov)–1847 (May) Richard Robert Madden, 1847–1849 Revitt Henry Bland, 1849 (Jan)–1850 (Mar) Thomas Newte Yule (Acting), 1850 (Mar–Oct) Alexander John Piesse, 1850 (Nov)–1851 (Mar) Thomas Newte Yule (Acting), 1851 (Mar–Dec) -

Cradleof the Colony

CRADLE OF THE COLONY A STORY OF GUILDFORD AND THE SWAN VALLEY FEATURING ITEMS FROM THE SWAN GUILDFORD HISTORICAL SOCIETY COLLECTION. WESTERN AUSTRALIA’S THIRD MOST SIGNIFICANT COLLECTION. This exhibition is a partnership project between the City of Swan and the Swan Guildford Historical Society, support funded by Lotterywest. We acknowledge the traditional custodians of this land. WELCOME TO HISTORIC GUILDFORD THIS EXHIBITION IS DESIGNED TO GIVE AN OVERVIEW OF THE HISTORY OF GUILDFORD AND THE SWAN VALLEY FROM CAPTAIN JAMES STIRLING’S EXPEDITION UP THE SWAN RIVER IN 1827 UNTIL THE PRESENT DAY. The Swan River Colony was established in 1829 as a free settlement with British support under Stirling as lieutenant governor. Land was the attraction for new settlers. Stirling elected to take 100,000 acres in lieu of a stipend (payment). Initial contact with the traditional Aboriginal owners was friendly but following settlement the differences in approach to land and cultural attitudes soon led to confl ict. Introduced diseases also had a dramatic impact on Aboriginal society. The Swan Valley, with Guildford as the Portrait of Admiral James Stirling, First Governor of Western Australia c1840 planned market town and transport Courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, ML 15. hub, was the agricultural cradle of the new settlement. The infant colony struggled to survive until the arrival of convicts in the 1850s. The next boom period was the gold rush of the 1890s followed by two world wars and a depression in the fi rst half of the 20th century. Today Guildford is a recognised historic town classifi ed by the National Trust, and the Swan Valley is one of Western Australia’s most visited tourism destinations.