On the Specificity of Middle Eastern Constitutionalism Chibli Mallat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jerusalem: City of Dreams, City of Sorrows

1 JERUSALEM: CITY OF DREAMS, CITY OF SORROWS More than ever before, urban historians tell us that global cities tend to look very much alike. For U.S. students. the“ look alike” perspective makes it more difficult to empathize with and to understand cultures and societies other than their own. The admittedly superficial similarities of global cities with U.S. ones leads to misunderstandings and confusion. The multiplicity of cybercafés, high-rise buildings, bars and discothèques, international hotels, restaurants, and boutique retailers in shopping malls and multiplex cinemas gives these global cities the appearances of familiarity. The ubiquity of schools, university campuses, signs, streetlights, and urban transportation systems can only add to an outsider’s “cultural and social blindness.” Prevailing U.S. learning goals that underscore American values of individualism, self-confidence, and material comfort are, more often than not, obstacles for any quick study or understanding of world cultures and societies by visiting U.S. student and faculty.1 Therefore, international educators need to look for and find ways in which their students are able to look beyond the veneer of the modern global city through careful program planning and learning strategies that seek to affect the students in their “reading and learning” about these fertile centers of liberal learning. As the students become acquainted with the streets, neighborhoods, and urban centers of their global city, their understanding of its ways and habits is embellished and enriched by the walls, neighborhoods, institutions, and archaeological sites that might otherwise cause them their “cultural and social blindness.” Jerusalem is more than an intriguing global historical city. -

Acknowledgments 1 Background

NOTES Acknowledgments 1. Science and Science Policy in the Arab World , published by Centre for Arab Unity Studies 1979 and Croom Helm, 1980; and The Arab World and the Challenges of Science and Technology: Progress without Change , published by Centre for Arab Unity Studies, 1999. 1 Background 1. These numbers, as we shall see, are approximate. 2. “10 Emerging Technologies 2009,” Technology Review 102, 2 (April 2009), 37–54. 3. For a report on the ongoing debate in Germany on this issue, see Carter Dougherty, “Debate in Germany: Research or Manufacturing,” New York Times , August 12, 2009. 4. See Alvin and Heidi Toffler, Revolutionary Wealth (Currency Doubleday, 2006), 94. 5. Ibid., part 6, 146ff. 6. Gavin Weightman, The Industrial Revolutionaries: The Making of the Modern World (Grove Press, 2007). 7. It is speculated that the steam engine may have been invented earlier by Pharaonic priests and that knowledge of this invention was available to Hero of Alexandria at about 10 to 60 CE 8. It seems that cats became domesticated around 1450 BC and were used at that time to protect granaries in Egypt. See, for an interesting account of the cat in Egypt, Jaromir Malek, The Cat in Ancient Egypt (London: The British Museum Press, 2006), 54–55, Revised Edition. 9. Research concerning the conversion to steam shipping was already well under way. See Christine Macleod, Jeremy Stein, Jennifer Tann, and James Andrew, “Making Waves: The Royal Navy’s Management of Invention and Innovation in Steam Shipping, 1815–1832,” History and Technology , 16 (2000), 307–333. 10. Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (Allen Lane, 2007). -

Studies of the Eastern World Page 1 of 4

IUPUI/IMA Community Project > Activities > Instructional Units > Studies of the Eastern World Page 1 of 4 Studies of the Eastern World by Aimee Burman and Elizabeth Danville Middle School Danville Community School Corporation Studies of the Eastern Worlds presents aspects of Eastern culture through the presentation and viewing of visual images. Students will view artwork from Thailand, China, Indian, Japan, Pakistan, Burma, Indonesia, Philippines, and Korea. Students will be challenged to discover similarities and differences in the culture of each of the countries by looking at the art from each country. The students will test their hypothesis and assumptions through further research in the media center. The final presentation of their research will include the creation of a cultural map of the Eastern World. Lesson Plan Title: Studies of the Eastern Worlds: Cultural Maps Keywords: Eastern World/Cultures/History/Geography/Interdisciplinary Curriculum Area: Cultures Grade Level: Seventh grade Appropriate Group Size: Whole Class Time Expected to Complete Instructional Plan: 5 days Instructional Objectives: 1. Students will learn of aspects of eastern culture by viewing various artworks. 2. Students will determine similarities and differences of eastern culture in the various countries by viewing the artworks. 3. Students will work successfully in cooperative learning groups. 4. Students will discover religion, language, life styles, and historical figures in various eastern world countries through researching. 5. Students will present the material they discover to classmates using visuals. Indiana State Proficiencies: Indiana State Social Studies Proficiencies Guide Geographical Relationships: Explain the relationship between physical and cultural features on the earth’s surface. Economics: Demonstrate the influence of physical and cultural factors upon the economic systems found in countries of the Eastern World. -

[email protected] Bloomington, in 47405 Website

JASON SION MOKHTARIAN Department of Religious Studies Indiana University 230 Sycamore Hall, 1033 E. 3rd St. Email: [email protected] Bloomington, IN 47405 Website: www.jasonmokhtarian.com ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT Indiana University, Associate Professor with tenure (2018-present; Assistant Professor, 2011-2018), Department of Religious Studies Director, Olamot Center for Scholarly and Cultural Exchange with Israel (2018– present) Core Faculty, Borns Jewish Studies Program Adjunct Professor in Central Eurasian Studies, History, Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, Ancient Studies, and Islamic Studies EDUCATION University of California, Los Angeles Ph.D., Dept. of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures (Late Antique Judaism), 2011 University of California, Los Angeles M.A., Dept. of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures (Ancient Iranian Studies), 2007 Hebrew University of Jerusalem Research Fellow in Talmud and Iranian Studies, 2006 University of Chicago Divinity School M.A., History of Judaism, 2004 University of Chicago B.A./A.M., English and Religious Studies, 2001 RESEARCH INTERESTS Rabbinics, ancient Iranian studies, Talmud in its Sasanian context, comparative religion, ancient Jewish magic and medicine, Aramaic magic bowls, Zoroastrianism, Middle Persian (Pahlavi) literature, Judeo-Persian literature, religious interactions in early Islamic Iran, Jews of Persia RESEARCH LANGUAGES Hebrew, Aramaic (Talmud), Old Persian, Middle Persian, Modern Persian, Avestan, Arabic, French, German MOKHTARIAN, Curriculum Vitae 2 ______________________________________________________________________________________________ PUBLICATIONS BOOKS Rabbis, Sorcerers, Kings, and Priests: The Culture of the Talmud in Ancient Iran. Oakland: University of California Press, 2015. Medicine in the Talmud: Natural and Supernatural Remedies between Magic and Science. Under review. JOURNAL ARTICLES “Zoroastrian Polemics against Judaism in the Škand Gumānīg Wizār (Doubt-Dispelling Exposition).” Mizan: Journal for the Study of Muslim Societies and Civilizations 3 (2018). -

English/Language Arts I (9Th G

Course ID Course Name Course Description Course Level Course Subject Area 01001 ELA I (9th grade) English/Language Arts I (9th grade) courses build upon students’ prior knowledge of grammar, vocabulary, word usage, and the mechanics of writing and usually include the four aspects of Secondary English Language and Literature language use: reading, writing, speaking, and listening. Typically, these courses introduce and define various genres of literature, with writing exercises often linked to reading selections. 01002 ELA II (10th grade) English/Language Arts II (10th grade) courses usually offer a balanced focus on composition and literature. Typically, students learn about the alternate aims and audiences of written Secondary English Language and Literature compositions by writing persuasive, critical, and creative multi-paragraph essays and compositions. Through the study of various genres of literature, students can improve their reading rate and comprehension and develop the skills to determine the author’s intent and theme and to recognize the techniques used by the author to deliver his or her message. 01003CC ELA III (Common Core) (11th grade) English/Language Arts III (11th grade) Common Core courses provide instruction designed to prepare students for the Regents Exam in English Language Arts (Common Core). Secondary English Language and Literature 01004 ELA IV (12th grade) English/Language Arts IV (12th grade) courses blend composition and literature into a cohesive whole as students write critical and comparative analyses of selected literature, continuing to Secondary English Language and Literature develop their language arts skills. Typically, students primarily write multi-paragraph essays, but they may also write one or more major research papers. -

A Comparison of Sawt Al-Arab ("Voice of the Arabs") and A1 Jazeera News Channel

The Development of Pan-Arab Broadcasting Under Authoritarian Regimes -A Comparison of Sawt al-Arab ("Voice of the Arabs") and A1 Jazeera News Channel Nawal Musleh-Motut Bachelor of Arts, Simon Fraser University 2004 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of fistory O Nawal Musleh-Motut 2006 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2006 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Approval Name: Nawal Musleh-Motut Degree: Master of Arts, History Title of Thesis: The Development of Pan-Arab Broadcasting Under Authoritarian Regimes - A Comparison of SdwzdArab ("Voice of the Arabs") and AI Jazeera News Channel Examining Committee: Chair: Paul Sedra Assistant Professor of History William L. Cleveland Senior Supervisor Professor of History - Derryl N. MacLean Supervisor Associate Professor of History Thomas Kiihn Supervisor Assistant Professor of History Shane Gunster External Examiner Assistant Professor of Communication Date Defended/Approved: fl\lovenh 6~ kg. 2006 UN~~ER~WISIMON FRASER I' brary DECLARATION OF PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational -

Architecture, Body and Performance in the Ancient Near Eastern World S

AE0201 S02 Problems in Old World Archaeology Architecture, Body and Performance in the Ancient Near Eastern World Artemis A.W. and Martha Sharp Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World Brown University Fall 2006 S y l l a b u s Meets Fridays 3:00-5:20 pm (the so-called O-hour) in Joukowsky Institute Seminar Room 203 Instructor: Ömür Harmansah (Visiting Assistant Professor) Office Hours: Tuesday 10-12 am. (By appointment) Office: Joukowsky Institute (70 Waterman St.) Room 202 E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 401-863-6411 Course Description This seminar investigates the relationship between bodily practices, social performances and production of space, using case studies drawn from ancient Mesopotamia, Anatolia and Syria. Employing contemporary critical theories on the body, materiality and social practices, new theories of the making of architectural spaces and landscapes will be explored with respect to multiple geographical, historical contexts in the Ancient Near East. Contemporary discourses on body and performance in cultural studies and social theory have flourished drastically in the last two decades and continue to offer new avenues of research in the social sciences and the humanities. In this seminar, our goal is, on the one hand, to explore these new theoretical writings on embodiment, agency, subjectivity, bodily practices, social performances, spectacles, materiality and spatiality of body. On the other hand, we will review recent archaeological work, historical and literary sources from the ancient Near East, and consider their scholarly interpretations influenced by contemporary discourses. Our task remains to be posing new research questions to the material culture of the ancient Near Eastern world in the light of our theoretical readings and attempt to device alternative approaches in understanding this corpus of archaeological evidence. -

A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Confucian Values in China, Korea, Japan, and Taiwan Yan Bing Zhang, Mei-Chen Lin, Akihiko Nonaka, & Khisu Beom

Communication Research Reports Vol. 22, No. 2, June 2005, pp. 107Á/115 Harmony, Hierarchy and Conservatism: A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Confucian Values in China, Korea, Japan, and Taiwan Yan Bing Zhang, Mei-Chen Lin, Akihiko Nonaka, & Khisu Beom This study examined 1,631 college students’ endorsement of traditional Confucian values in four East Asian cultural contexts (i.e., China, Korea, Japan and Taiwan). Findings showed that young people endorsed values of interpersonal harmony the most, followed by the relational hierarchy and traditional conservatism respectively. Results also indicated that participants in China provided the highest ratings for interpersonal harmony and relational hierarchy among the four cultures. Finally, results demonstrated that Japanese females were more conservative than Japanese males and females in China and Taiwan. Results were discussed in the philosophical tradition of Confucianism, globalization and culture change in the East Asian cultures. Keywords: Confucian Values; China; South Korea; Japan; Taiwan; Harmony; Hierarchy; Conservatism; Gender Introduction The major interest of cross-cultural studies tends to focus on how cultures differed in the outcome variable (e.g., conflict management style) than in the input variable (i.e., cultural values). Cultural values are frequently treated as a post-hoc explanation to Yan Bing Zhang (PhD, University of Kansas) is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication Studies at the University of Kansas. Mei-Chen Lin (PhD, University of Kansas) is an Assistant Professor in the School of Communication Studies at Kent State University. Akihiko Nonaka is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Communication Studies at Seinan Gakuin University, and an instructor at Fukuoka University, Japan. -

B.Sc in Culinary Science(2018-19)-13.6.19.Pdf

MAULANA ABUL KALAM AZAD UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY , WB Syllabus of B.Sc. in Culinary Science Effective from Academic Session 2018-2019 1ST YEAR SL CODE Paper Marks Total Contact Credits No Hours SEMESTER I 1 Introduction to Hospitality 100 32 3 BSCA-101 Industry(Th.) 2 Basics of Food 100 32 3 BSCA-102 Production(Th.) 3 Basics of Food & Beverage 100 32 3 BSCA-103 Service (Th.) 4 Introduction to Front office 100 30 3 BSCA-104 and Accommodation (Th.) 5 BSCA-105 Communication Skills- (Th.) 100 32 2 6 BSCA-191 Culinary Skills I (Pr.) 100 44 2 7 BSCA-192 Baking Skills I(Pr.) 100 48 2 8 Restaurant Service (Pr.) 100 34 2 BSCA-193 TOTAL 800 20 SEMESTER II 1 BSCA-201 Indian Cuisine (Th.) 100 32 3 2 BSCA-202 Regional & Staple Food(Th.) 100 32 2 3 Food & Beverage Studies 100 32 3 BSCA-203 (Th.) 4 Nutrition & Food Science 100 32 4 BSCA-204 (Th.) 5 International Culinary Art 100 40 2 BSCA-291 (Pr.) 6 BSCA-292 Indian Culinary Art (Pr.) 100 40 2 7 BSCA-293 Baking Skills II(Pr.) 100 36 2 8 Fundamentals of Information 100 36 2 BSCA-294 Technology (Pr.) Total 800 20 MAULANA ABUL KALAM AZAD UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY , WB Syllabus of B.Sc. in Culinary Science Effective from Academic Session 2018-2019 2ND YEAR SL CODE Paper Marks Total Contact Credits No Hours SEMESTER III 1 Eastern Indian Cuisine and 100 30 3 BSCA-301 Culture (Th.) 2 BSCA-302 Beverage Studies (Th.) 100 34 3 3 BSCA-303 Food Cost Controls (Th.) 100 34 3 4 BSCA-304 Larder &Charcuterie (Th.) 100 34 3 5 BSCA-305 Gastronomy (Th.) 100 34 2 6 Regional Indian Cuisine 100 36 2 BSCA-391 (Quantity) (Pr.) 7 Intermediate Bakery & 100 40 2 BSCA-392 Confectionary (Pr.) 8 Larder & Short Order Cookery 100 28 2 BSCA-393 (Pr.) Total 800 20 SEMESTER IV 1 BSCA 481 Industrial Training (16 weeks) 400 14 2 BSCA 482 Training Report & Log Book 200 3 3 BSCA 483 Viva Voce 200 3 Total 800 20 MAULANA ABUL KALAM AZAD UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY , WB Syllabus of B.Sc. -

The Origins of Kuwait's National Assembly

THE ORIGINS OF KUWAIT’S NATIONAL ASSEMBLY MICHAEL HERB LSE Kuwait Programme Paper Series | 39 About the Middle East Centre The LSE Middle East Centre opened in 2010. It builds on LSE’s long engagement with the Middle East and provides a central hub for the wide range of research on the region carried out at LSE. The Middle East Centre aims to enhance understanding and develop rigorous research on the societies, economies, polities, and international relations of the region. The Centre promotes both specialised knowledge and public understanding of this crucial area and has outstanding strengths in interdisciplinary research and in regional expertise. As one of the world’s leading social science institutions, LSE comprises departments covering all branches of the social sciences. The Middle East Centre harnesses this expertise to promote innovative research and training on the region. About the Kuwait Programme The Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States is a multidisciplinary global research programme based in the LSE Middle East Centre and led by Professor Toby Dodge. The Programme currently funds a number of large scale col- laborative research projects including projects on healthcare in Kuwait led by LSE Health, urban form and infrastructure in Kuwait and other Asian cities led by LSE Cities, and Dr Steffen Hertog’s comparative work on the political economy of the MENA region. The Kuwait Programme organises public lectures, seminars and workshops, produces an acclaimed working paper series, supports post-doctoral researchers and PhD students and develops academic networks between LSE and Gulf institutions. The Programme is funded by the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences. -

Ssemester-III

MAULANA ABUL KALAM AZAD UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, WB Syllabus of B.Sc. in Culinary Science Effective from Academic Session 2018-2019 SSemester-III PAPER- Eastern Indian Cuisine and Culture CODE-BSCA 301 CREDIT- 3 Topic Hours States of this Region; Traditional Dresses; Etiquettes 06 Bengali Cuisine 06 Odiyan, Assamese and Bihari Cuisine 06 Major Fairs & Festivals of the Region 06 North Eastern cuisine, Culture and Festival 06 REFERENCE BOOKS:- 1. Pollan, M. 2006. The Omnivore’s Dilemma. New York: Penguin. [Part 1, Pp 15-109]. 2. Holmes. S. (2013). Fresh Fruit: Broken Bodies. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press MAULANA ABUL KALAM AZAD UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, WB Syllabus of B.Sc. in Culinary Science Effective from Academic Session 2018-2019 PAPER- Beverage Studies CODE-BSCA 302 CREDIT-3 TOPICS HOURS Introduction to Beverages Classification of Beverages; Beer, Perry and Cider 4 Fermentation & alcohol Digestion and effects on the body Wine production Wine 6 storage & service White grapes of the world White wines of France; Cooperage & wood aging; White 12 wines of Germany; Red grapes of the world Red wines of Burgundy & the Rhône; Red wines of Bordeaux ; Wines of World: Austria, Hungary, Greece, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Canada, Chile & Argentina; Champagne, sherry & port Aperitifs & fortified wine; Matching wine and food Distilled brown spirits Cognac & brandy ; Distilled clear spirits Liqueurs & cordials 4 Cocktails & bar equipment Cocktails 4 Types and Methods of Making Low & non alcohol beverages 4 References: A to Z of Whisky, Gavin D. Smith About Wine, J. Patrick Henderson & Dellie Rex Alexis Lichine’s Encyclopedia of Wines & Spirits, Alexis Lichine All American Cheese and Wine Book, Laura Werlin American Journal of Enology & Viticulture, Modification of a Standardized System of Wine Aroma Terminology, A. -

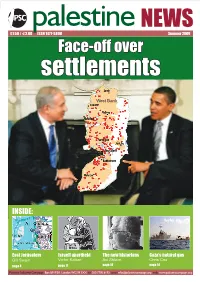

Face-Off Over Settlements

summer09 palestine NEWS 1 £1.50 / €2.00 ISSN 1477-5808 Summer 2009 Face-off over settlements West Bank INSIDE: East Jerusalem Israeli apartheid The new historians Gaza’s natural gas Gill Swain Victor Kattan Avi Shlaim Chris Cox page 4 page 11 page 14 page 18 Palestine Solidarity Campaign Box BM PSA London WC1N 3XX tel 020 7700 6192 email [email protected] web www.palestinecampaign.org 2 palestine NEWS summer09 Contents 3 Can Obama deliver? Betty Hunter examines the clash between Obama and Netanyahu over settlements 4 East Jerusalem — a stolen city Dramatic map reveals how settlements are spreading through Jerusalem 6 Q: Where are the Palestinian Ghandis? A: In Jail Bekah Wolf reports on a grassroots resistance movement — and the Israeli response 9 Trade unionists shocked and angry Kiri Tunks and Bernard Regan on a trade union delegation to the OPTs 10 BBC betrays Jeremy Bowen How the BBC Trust caved in to pressure and censured its Middle East editor Cover map: fmep_v18n1_map. pdf from the Foundation for 11 Israel guilty of colonialism and apartheid Middle East Peace. Victor Kattan on a hard-hitting South African report www.fmep.org 12 Dialogue with the Diaspora ISSN 1477 - 5808 Jeff Halper reflects on the reasons for the uproar he caused in Australia Also in this issue... 14 The ‘new history’ and the Nakba Gaza music school reopens Prof Avi Shlaim describes the impact of re-examining the past page 21 16 Operation ‘Hasbara’ Diane Langford examines how the Israeli propaganda machine manipulates the message 17 Between a rock and