The Integration of Dance As a Dramatic Element in Broadway Musical Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy And

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Tsung-Hsin Lee, M.A. Graduate Program in Dance Studies The Ohio State University 2020 Dissertation Committee Hannah Kosstrin, Advisor Harmony Bench Danielle Fosler-Lussier Morgan Liu Copyrighted by Tsung-Hsin Lee 2020 2 Abstract This dissertation “Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980” examines the transnational history of American modern dance between the United States and Taiwan during the Cold War era. From the 1950s to the 1980s, the Carmen De Lavallade-Alvin Ailey, José Limón, Paul Taylor, Martha Graham, and Alwin Nikolais dance companies toured to Taiwan under the auspices of the U.S. State Department. At the same time, Chinese American choreographers Al Chungliang Huang and Yen Lu Wong also visited Taiwan, teaching and presenting American modern dance. These visits served as diplomatic gestures between the members of the so-called Free World led by the U.S. Taiwanese audiences perceived American dance modernity through mixed interpretations under the Cold War rhetoric of freedom that the U.S. sold and disseminated through dance diplomacy. I explore the heterogeneous shaping forces from multiple engaging individuals and institutions that assemble this diplomatic history of dance, resulting in outcomes influencing dance histories of the U.S. and Taiwan for different ends. I argue that Taiwanese audiences interpreted American dance modernity as a means of embodiment to advocate for freedom and social change. -

SMTA Catalog Complete

The Integrated Broadway Library Index including the complete works from 34 collections: sorted by musical HL The Singer's Musical Theatre Anthology (22 vols) A The Singer's Library of Musical Theatre (8 vols) TMTC The Teen's Musical Theatre Collection (2 vols) MTAT The Musical Theatre Anthology for Teens (2 vols) Publishers: HL = Hal Leonard; A = Alfred *denotes a song absent in the revised edition Pub Voice Vol Page Song Title Musical Title HL S 4 161 He Plays the Violin 1776 HL T 4 198 Mama, Look Sharp 1776 HL B 4 180 Molasses to Rum 1776 HL S 5 246 The Girl in 14G (not from a musical) HL Duet 1 96 A Man and A Woman 110 In The Shade HL B 5 146 Gonna Be Another Hot Day 110 in the Shade HL S 2 156 Is It Really Me? 110 in the Shade A S 1 32 Is It Really Me? 110 in the Shade HL S 4 117 Love, Don't Turn Away 110 in the Shade A S 1 22 Love, Don't Turn Away 110 in the Shade HL S 1 177 Old Maid 110 in the Shade HL S 2 150 Raunchy 110 in the Shade HL S 2 159 Simple Little Things 110 in the Shade A S 1 27 Simple Little Things 110 in the Shade HL S 5 194 Take Care of This House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue A T 2 41 Dames 42nd Street HL B 5 98 Lullaby of Broadway 42nd Street A B 1 23 Lullaby of Broadway 42nd Street HL T 3 200 Coffee (In a Cardboard Cup) 70, Girls, 70 HL Mezz 1 78 Dance: Ten, Looks: Three A Chorus Line HL T 4 30 I Can Do That A Chorus Line HL YW MTAT 120 Nothing A Chorus Line HL Mezz 3 68 Nothing A Chorus Line HL Mezz 4 70 The Music and the Mirror A Chorus Line HL Mezz 2 64 What I Did for Love A Chorus Line HL T 4 42 One More Beautiful -

SMU Research, Volume 13 Office of Public Affairs

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar SMU Research Magazine Office of Research and Graduate Studies 2006 SMU Research, Volume 13 Office of Public Affairs Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/research_magazine Recommended Citation Office of Public Affairs, "SMU Research, Volume 13" (2006). SMU Research Magazine. 1. https://scholar.smu.edu/research_magazine/1 This document is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of Research and Graduate Studies at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Research Magazine by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. Message from the Dean Research Strengthens Ouest for the Best SMURasaarch www.smu.edu/newsinfo/research SMU &much is pmduced annually by rhe Office of PubHc Affijn for the Office of Research and Graduate Studies of Southern Methodist Universiry. Please send correspondence ro Office of Research and am pleased to report that we have had a very busy and productive Graduate Studies, SMU, PO Box 750240, Dallas TX 75275-0240, or call 2 14-768-4345. E-mail: [email protected] year in the Office of Research and Graduate Studies. We have provid Ofnca of Public Affairs Swan White ed important funds to support the work of SMU faculty and graduate E<Hror Sherry Myres students; we have put in place measures to increase funding for exter Creative Director VictoriaOa.ry nal research; we have welcomed aboard a new Ph.D. program in Designer Hillsman S. Jackson English; and we have continued to patent and market the significant Photographer Contributors: Lisa Castello, Meredith Dickenson, Nancy George. -

The Great American Songbook in the Classical Voice Studio

THE GREAT AMERICAN SONGBOOK IN THE CLASSICAL VOICE STUDIO BY KATHERINE POLIT Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May, 2014 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music. ___________________________________ Patricia Wise, Research Director and Chair __________________________________ Gary Arvin __________________________________ Raymond Fellman __________________________________ Marietta Simpson ii For My Grandmothers, Patricia Phillips and Leah Polit iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my sincerest thanks to the members of my committee—Professor Patricia Wise, Professor Gary Arvin, Professor Marietta Simpson and Professor Raymond Fellman—whose time and help on this project has been invaluable. I would like to especially thank Professor Wise for guiding me through my education at Indiana University. I am honored to have her as a teacher, mentor and friend. I am also grateful to Professor Arvin for helping me in variety of roles. He has been an exemplary vocal coach and mentor throughout my studies. I would like to give special thanks to Mary Ann Hart, who stepped in to help throughout my qualifying examinations, as well as Dr. Ayana Smith, who served as my minor field advisor. Finally, I would like to thank my family for their love and support throughout my many degrees. Your unwavering encouragement is the reason I have been -

News from the Jerome Robbins Foundation Vol

NEWS FROM THE JEROME ROBBINS FOUNDATION VOL. 6, NO. 1 (2019) The Jerome Robbins Dance Division: 75 Years of Innovation and Advocacy for Dance by Arlene Yu, Collections Manager, Jerome Robbins Dance Division Scenario for Salvatore Taglioni's Atlanta ed Ippomene in Balli di Salvatore Taglioni, 1814–65. Isadora Duncan, 1915–18. Photo by Arnold Genthe. Black Fiddler: Prejudice and the Negro, aired on ABC-TV on August 7, 1969. New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, “backstage.” With this issue, we celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Jerome Robbins History Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. In 1944, an enterprising young librarian at The New York Public Library named One of New York City’s great cultural treasures, it is the largest and Genevieve Oswald was asked to manage a small collection of dance materials most diverse dance archive in the world. It offers the public free access in the Music Division. By 1947, her title had officially changed to Curator and the to dance history through its letters, manuscripts, books, periodicals, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, known simply as the Dance Collection for many prints, photographs, videos, films, oral history recordings, programs and years, has since grown to include tens of thousands of books; tens of thousands clippings. It offers a wide variety of programs and exhibitions through- of reels of moving image materials, original performance documentations, audio, out the year. Additionally, through its Dance Education Coordinator, it and oral histories; hundreds of thousands of loose photographs and negatives; reaches many in public and private schools and the branch libraries. -

Gemze De Lappe Career Highlights

DATE END (if avail) LOCATION SHOW/EVENT ROLE (if applicable) COMPANY NOTES 1922/02/28 Portsmouth, VA Born Gemze Mary de Lappe BORN Performed during the summer - would do ballets during intermission of productions of 1931/00/00 1939/00/00 Lewisohn Stadium, NY Michael Fokine Ballet dancer Michael Folkine recent Broadway shows. 1941/11/05 1941/11/11 New York La Vie Parisienne Ballet 44th St. New Opera Company 1943/11/15 1945/01/00 Chicago Oklahoma! Aggie National Tour with John Raitt Premiere at the old Metropolitan Opera House - Jerome Robbins choreographed Fancy Free, which was later developed into 1944/04/18 New York Fancy Free [Jerome Robbins] dancer Ballet Theatre On the Town 1945/01/08 St. Louis Oklahoma! Aggie 1945/01/29 1945/02/10 Milwaukee Oklahoma! Aggie 1945/03/05 Detroit Oklahoma! Aggie 1945/04/09 Pittsburgh Oklahoma! Aggie 1945/06/18 Philadelphia Oklahoma! Aggie National Tour 1946/01/22 Minneapolis Oklahoma! Ellen/Dream Laurey National Tour Ellen/Dream Laurey 1946/08/19 New York Oklahoma! (replacement) St. James 1947/04/30 London Oklahoma! Dream Laurey Theatre Royal Drury Lane with Howard Keel Melbourne, Victoria, Recreated 1949/02/19 Australia Oklahoma! Choreography Australia Premiere 1951/03/29 New York The King and I King Simon of Legree St. James 1951/10/01 Philadelphia Paint Your Wagon Yvonne Pre-Broadway Tryout 1951/10/08 Boston Paint Your Wagon Yvonne Pre-Broadway Tryout 1951/11/12 1952/07/19 New York Paint Your Wagon Yvonne Shubert The Donaldson Awards were a set of theatre awards established in 1944 by the drama critic Robert Francis in honor of W. -

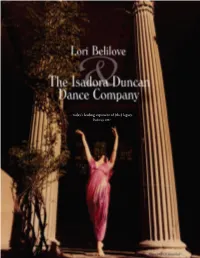

Today's Leading Exponent of (The) Legacy

... today’s leading exponent of (the) legacy. Backstage 2007 THE DANCER OF THE FUTURE will be one whose body and soul have grown so harmoniously together that the natural language of that soul will have become the movement of the human body. The dancer will not belong to a nation but to all humanity. She will not dance in the form of nymph, nor fairy, nor coquette, but in the form of woman in her greatest and purest expression. From all parts of her body shall shine radiant intelligence, bringing to the world the message of the aspirations of thousands of women. She shall dance the freedom of women – with the highest intelligence in the freest body. What speaks to me is that Isadora Duncan was inspired foremost by a passion for life, for living soulfully in the moment. ISADORA DUNCAN LORI BELILOVE Table of Contents History, Vision, and Overview 6 The Three Wings of the Isadora Duncan Dance Foundation I. The Performing Company 8 II. The School 12 ISADORA DUNCAN DANCE FOUNDATION is a 501(C)(3) non-profit organization III. The Historical Archive 16 recognized by the New York State Charities Bureau. Who Was Isadora Duncan? 18 141 West 26th Street, 3rd Floor New York, NY 10001-6800 Who is Lori Belilove? 26 212-691-5040 www.isadoraduncan.org An Interview 28 © All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the Isadora Duncan Dance Foundation. Conceived by James Richard Belilove. Prepared and compiled by Chantal D’Aulnis. Interviews with Lori Belilove based on published articles in Smithsonian, Dance Magazine, The New Yorker, Dance Teacher Now, Dancer Magazine, Brazil Associated Press, and Dance Australia. -

THE SINGER's MUSICAL THEATRE ANTHOLOGY Series ALL SOPRANO VOLUMES

THE SINGER'S MUSICAL THEATRE ANTHOLOGY series ALL SOPRANO VOLUMES S1 = Volume 1 S2 = Volume 2 S3 = Volume 3 S4 = Volume 4 S5 = Volume 5 S-Teen = Teen's Edition S16 = Soprano "16-Bar" Audition Alphabetically by Song Title SONG SHOW VOLUME Ah! Sweet Mystery of Life Naughty Marietta S3, S16 All Through the Night Anything Goes S2 And This Is My Beloved Kismet S2 Another Suitcase in Another Hall Evita S2, S16 Another Winter in a Summer Town Grey Gardens S5, S16 Anything Can Happen Mary Poppins S5 Around the World Grey Gardens S5 S2, S-Teen, Art Is Calling for Me The Enchantress S16 Barbara Song The Threepenny Opera S1 Baubles, Bangles and Beads Kismet S5 S5, S-Teen, The Beauty Is The Light in the Piazza S16 Before I Gaze at You Again Camelot S3 Begin the Beguine Jubilee S5 Belle (Reprise) Beauty and the Beast S-Teen Bewitched Pal Joey S4, S16 Bill Show Boat S1 Bride's Lament The Drowsy Chaperone S5 A Call from the Vatican Nine S2, S16 Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man Show Boat S1, S16 Children of the Wind Rags S4, S16 S4, S-Teen, Children Will Listen Into the Woods S16 Christmas Lullaby Songs for a New World S3 Climb Ev’ry Mountain The Sound of Music S1 Come Home Allegro S1 Cry Like the Wind Do Re Mi S5, S16 Daddy's Girl Grey Gardens S5, S16 Dear Friend She Loves Me S2, S16 Fable The Light in the Piazza S5 Falling in Love with Love The Boys from Syracuse S1, S16 S1, S-Teen, Far from the Home I Love Fiddler on the Roof S16 Fascinating Rhythm Lady, Be Good! S5 Feelings The Apple Tree S3, S16 The Flagmaker, 1775 Songs for a New World S5 Follow Your -

Teen's Musical Theatre Songfinder

TEEN’S MUSICAL THEATRE SONGFINDER Alphabetically by Song Alphabetically by Show MUSICAL THEATRE SONGS FOR TEENS - COMPLETE LIST (Alphabetical by SONG Title) SHOW TITLE SONG TITLE PUBLICATION TITLE ITEM NUMBER 21 Guns American Idiot Broadway Presents! Audition Musical Theatre Anthology - Young Male Edition 00322356 Book/2-CDs Pack A La Volonté du Peuple Les Misérables Songs of Boublil & Schönberg, The - Men’s Edition 00001193 Men’s Edition Ad-dressing of Cats, The Cats Andrew Lloyd Webber For Singers - Men’s Edition 00001185 Men’s Edition Adelaide’s Lament Guys and Dolls Broadway Junior Songbook - Young Women’s Edition 00740327 Book/CD Pack Adelaide’s Lament Guys and Dolls Musical Theatre Anthology For Teens - Young Women’s Edition 00740157 Book only Adelaide’s Lament Guys and Dolls Musical Theatre Anthology For Teens - Young Women’s Edition 00740189 Book/CD Pack Ah, But Underneath Follies Complete Follies Collection, The 00313306 Book only Ah, Paris Follies Complete Follies Collection, The 00313306 Book only Ain’t Misbehavin’ Ain’t Misbehavin’ Broadway For Teens - Young Women’s Edition 00000402 Book/CD Pack All for You Seussical the Musical Broadway Presents! Audition Musical Theatre Anthology - Young Female Edition 00322304 Book/2-CDs Pack All for You Seussical the Musical Broadway Presents! Teens' Musical Theatre Anthology - Female Edition 00322200 Book/2-CDs Pack All Good Gifts Godspell Broadway Junior Songbook - Young Men’s Edition 00740328 Book/CD Pack All Good Gifts Godspell Musical Theatre Anthology For Teens - Young Men’s Edition -

The Gold Rush Is On

CONTENTS ' Week of February 9-Februory 15, 1958 Cover Story (7 Lively Arte).. 1 This Week'i Movie* 35 TeleVue Mailbag 4 Tbi. Week in Poblic Affair*.. 35 This Week'* Program* 4-31 Thi. Week ie Sport* 36 O Index of Show* and 32-33 Thi* Week'* Color Show* - 36 Stor* Trademark Ragittarad 0. S. Pot.nl OHic. Idltimora Program* .... 34 Thi* Week tor Children 36 Published by THI EVENING STAR NEWSPAPER CO., Waihington 4, 0. C, Telephone—Sterßog 3-5000 ' " ''' W • > S \ i | X .M.jfr&riiiglSj&'itf/ 'i * \*\ 'X V i ¦ ¦p> •> M|| * -•• 1 a| w i 9k - 1/< ¦ il UMij ». !¦ Mg M BH ' •* SB B • nj i % ¦ M x. x'” .iftfrti HPHHBHBBPBPBBBPPw HANDING OUT A LINE Choreographer Agnes DeMille corrects the flowing line of Gemze de Lappe’s arm during a rehearsal of “Gold Rush” for TV. James Mitchell (left) and Miss De Lappe will dance the leading roles when the De- Mille ballet is done on Seven Lively Arts Sunday, 5 p.m. f WTOP—9. Cover Story The Gold Rush Is On By BERNIE HARRISON leading spirits is Agnes De Mille, whose “Gold Star TV Critic Rush” will be performed Sunday on the Seven One of the most ambitious dance shows Lively Arts series (# to 6 p.m., WTOP—9). of the season will be presented Sunday after- Washington has already seen this De Mille noon and I’m willing to go way out on a limb special cm the stage, but Jim Mitchell, who will (a handsome one, if I say so myself) to predict be dancing the lead with Oemze (pronounced that it will be a smash. -

Donn Arden Papers

Guide to the Donn Arden Papers This finding aid was created by Su Kim Chung and Brooks Whittaker on July 27, 2018. Persistent URL for this finding aid: http://n2t.net/ark:/62930/f1k61t © 2018 The Regents of the University of Nevada. All rights reserved. University of Nevada, Las Vegas. University Libraries. Special Collections and Archives. Box 457010 4505 S. Maryland Parkway Las Vegas, Nevada 89154-7010 [email protected] Guide to the Donn Arden Papers Table of Contents Summary Information ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Note ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Scope and Contents Note ................................................................................................................................ 5 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................. 6 Related Materials ............................................................................................................................................. 7 Names and Subjects ....................................................................................................................................... -

The Dark Side of Hollywood

TCM Presents: The Dark Side of Hollywood Side of The Dark Presents: TCM I New York I November 20, 2018 New York Bonhams 580 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10022 24838 Presents +1 212 644 9001 bonhams.com The Dark Side of Hollywood AUCTIONEERS SINCE 1793 New York | November 20, 2018 TCM Presents... The Dark Side of Hollywood Tuesday November 20, 2018 at 1pm New York BONHAMS Please note that bids must be ILLUSTRATIONS REGISTRATION 580 Madison Avenue submitted no later than 4pm on Front cover: lot 191 IMPORTANT NOTICE New York, New York 10022 the day prior to the auction. New Inside front cover: lot 191 Please note that all customers, bonhams.com bidders must also provide proof Table of Contents: lot 179 irrespective of any previous activity of identity and address when Session page 1: lot 102 with Bonhams, are required to PREVIEW submitting bids. Session page 2: lot 131 complete the Bidder Registration Los Angeles Session page 3: lot 168 Form in advance of the sale. The Friday November 2, Please contact client services with Session page 4: lot 192 form can be found at the back of 10am to 5pm any bidding inquiries. Session page 5: lot 267 every catalogue and on our Saturday November 3, Session page 6: lot 263 website at www.bonhams.com and 12pm to 5pm Please see pages 152 to 155 Session page 7: lot 398 should be returned by email or Sunday November 4, for bidder information including Session page 8: lot 416 post to the specialist department 12pm to 5pm Conditions of Sale, after-sale Session page 9: lot 466 or to the bids department at collection and shipment.