Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

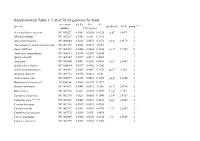

Supplementary Table 1: List of 76 Mt Genomes for Birds

Supplementary Table 1: List of 76 mt genomes for birds. accession Ka/Ks Ka Ks species speed(m/s) Ln S group * * number 13 mt genes Acrocephalus scirpaceus NC 010227 0.0464 0.0288 0.6228 6.6d 1.8871 2 Alectura lathami NC 007227 0.0343 0.032 0.9311 2 Anas platyrhynchos NC 009684 0.0252 0.0073 0.2873 18.5a 2.9178 2 Anomalopteryx didiformis (die out) NC 002779 0.0508 0.0027 0.054 1 Anser albifrons NC 004539 0.0468 0.0088 0.1856 16.1a 2.7788 2 Anseranas semipalmata NC 005933 0.0364 0.0207 0.5628 2 Apteryx haastii NC 002782 0.0599 0.0273 0.4561 1 Apus apus NC 008540 0.0401 0.0241 0.6431 10.6a 2.3609 2 Archilochus colubris NC 010094 0.0397 0.0382 0.9242 2 Ardea novaehollandiae NC 008551 0.0423 0.0067 0.1552 10.2c# 2.322 2 Arenaria interpres NC 003712 0.0378 0.0213 0.581 2 Aythya americana NC 000877 0.0309 0.0092 0.2987 24.4b 3.1946 2 Bambusicola thoracica* EU165706 0.0503 0.0144 0.2872 1 Branta canadensis NC 007011 0.0444 0.0092 0.206 16.7a 2.8154 2 Buteo buteo NC 003128 0.049 0.0167 0.3337 11.6a 2.451 2 Casuarius casuarius NC 002778 0.028 0.0085 0.3048 13.9f 2.6319 2 Cathartes aura * * * * NC 007628 0.0468 0.0239 0.4676 10.6c 2.3609 2 Ciconia boyciana NC 002196 0.0539 0.0031 0.0563 2 Ciconia ciconia NC 002197 0.0501 0.0029 0.0572 9.1d 2.2083 2 Cnemotriccus fuscatus NC 007975 0.0369 0.038 1.0476 2 Corvus frugilegus NC 002069 0.0428 0.0298 0.6526 13a 2.5649 2 Coturnix chinensis NC 004575 0.0325 0.0122 0.3762 2 Coturnix japonica NC 003408 0.0432 0.0128 0.2962 2 Cygnus columbianus NC 007691 0.0327 0.0089 0.2702 18.5a 2.9178 2 Dinornis giganteus -

Transantiquity

TransAntiquity TransAntiquity explores transgender practices, in particular cross-dressing, and their literary and figurative representations in antiquity. It offers a ground-breaking study of cross-dressing, both the social practice and its conceptualization, and its interaction with normative prescriptions on gender and sexuality in the ancient Mediterranean world. Special attention is paid to the reactions of the societies of the time, the impact transgender practices had on individuals’ symbolic and social capital, as well as the reactions of institutionalized power and the juridical systems. The variety of subjects and approaches demonstrates just how complex and widespread “transgender dynamics” were in antiquity. Domitilla Campanile (PhD 1992) is Associate Professor of Roman History at the University of Pisa, Italy. Filippo Carlà-Uhink is Lecturer in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Exeter, UK. After studying in Turin and Udine, he worked as a lecturer at the University of Heidelberg, Germany, and as Assistant Professor for Cultural History of Antiquity at the University of Mainz, Germany. Margherita Facella is Associate Professor of Greek History at the University of Pisa, Italy. She was Visiting Associate Professor at Northwestern University, USA, and a Research Fellow of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation at the University of Münster, Germany. Routledge monographs in classical studies Menander in Contexts Athens Transformed, 404–262 BC Edited by Alan H. Sommerstein From popular sovereignty to the dominion -

Des Clitumnus (8,8) Und Des Lacus Vadimo (8,20)

Sonderdrucke aus der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg ECKARD LEFÈVRE Plinius-Studien IV Die Naturauffassungen in den Beschreibungen der Quelle am Lacus Larius (4,30), des Clitumnus (8,8) und des Lacus Vadimo (8,20) Mit Tafeln XIII - XVI Originalbeitrag erschienen in: Gymnasium 95 (1988), S. [236] - 269 ECKARD LEFEVRE - FREIBURG I. BR. PLINIUS-STUDIEN IV Die Naturauffassung in den Beschreibungen der Quelle am Lacus Larius (4,30), des Clitumnus (8,8) und des Lacus Vadimo (8,20)* Mit Tafeln XIII-XVI quacumque enim ingredimur, in aliqua historia vestigium ponimus. Cic. De fin. 5,5 In seiner 1795 erschienenen Abhandlung Über naive und sentimen- talische Dichtung unterschied Friedrich von Schiller den mit der Natur in Einklang lebenden, den ‚naiven' Dichter (und Menschen) und den aus der Natur herausgetretenen, sich aber nach ihr zurücksehnenden, den ,sentimentalischen` Dichter (und Menschen). Der Dichter ist nach Schil- ler entweder Natur, oder er wird sie suchen. Im großen und ganzen war mit dieser Unterscheidung die verschiedene Ausprägung der griechischen und der modernen Dichtung gemeint. Schiller hat richtig gesehen, daß die Römer im Hinblick auf diese Definition den Modernen zuzuordnen sind': Horaz, der Dichter eines kultivierten und verdorbenen Weltalters, preist die ruhige Glückseligkeit in seinem Tibur, und ihn könnte man als den wahren Stifter dieser Diese Betrachtungen bilden zusammen mit den Plinius-Studien I-III (die in den Lite- raturhinweisen aufgeführt sind) eine Tetralogie zu Plinius' ästhetischer Naturauffas- sung. Dieses Thema ist hiermit abgeschlossen. [Inzwischen ist das interessante Buch von H. Mielsch, Die römische Villa. Architektur und Lebensform, München 1987, erschienen, in dem einiges zur Sprache kommt, was in dieser Tetralogie behandelt wird.] Auch in diesem Fall wurden die Briefe als eigenständige Kunstwerke ernst- genommen und jeweils als Ganzes der Interpretation zugrundegelegt. -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Bender et al. 10.1073/pnas.0802779105 Table S1. Species names and calculated numeric values pertaining to Fig. 1 Mitochondrially Nuclear encoded Nuclear encoded Species name encoded methionine, % methionine, % methionine, corrected, % Animals Primates Cebus albifrons 6.76 Cercopithecus aethiops 6.10 Colobus guereza 6.73 Gorilla gorilla 5.46 Homo sapiens 5.49 2.14 2.64 Hylobates lar 5.33 Lemur catta 6.50 Macaca mulatta 5.96 Macaca sylvanus 5.96 Nycticebus coucang 6.07 Pan paniscus 5.46 Pan troglodytes 5.38 Papio hamadryas 5.99 Pongo pygmaeus 5.04 Tarsius bancanus 6.74 Trachypithecus obscurus 6.18 Other mammals Acinonyx jubatus 6.86 Artibeus jamaicensis 6.43 Balaena mysticetus 6.04 Balaenoptera acutorostrata 6.17 Balaenoptera borealis 5.96 Balaenoptera musculus 5.78 Balaenoptera physalus 6.02 Berardius bairdii 6.01 Bos grunniens 7.04 Bos taurus 6.88 2.26 2.70 Canis familiaris 6.54 Capra hircus 6.84 Cavia porcellus 6.41 Ceratotherium simum 6.06 Choloepus didactylus 6.23 Crocidura russula 6.17 Dasypus novemcinctus 7.05 Didelphis virginiana 6.79 Dugong dugon 6.15 Echinops telfairi 6.32 Echinosorex gymnura 6.86 Elephas maximus 6.84 Equus asinus 6.01 Equus caballus 6.07 Erinaceus europaeus 7.34 Eschrichtius robustus 6.15 Eumetopias jubatus 6.77 Felis catus 6.62 Halichoerus grypus 6.46 Hemiechinus auritus 6.83 Herpestes javanicus 6.70 Hippopotamus amphibius 6.50 Hyperoodon ampullatus 6.04 Inia geoffrensis 6.20 Bender et al. www.pnas.org/cgi/content/short/0802779105 1of10 Mitochondrially Nuclear encoded Nuclear encoded Species -

Clifford Ando Department of Classics 1115 East 58Th Street

Clifford Ando Department of Classics 1115 East 58th Street Chicago, IL 60637 Phone: 773.834.6708 [email protected] September 2020 CURRENT POSITION • David B. and Clara E. Stern Distinguished Service Professor; Professor of Classics, History and in the College, University of Chicago • Chair, Department of Classics, University of Chicago (2017–2020, 2021-2024) EDITORIAL ACTIVITY • Series editor, Empire and After. University of Pennsylvania Press • Senior Editor, Bryn Mawr Classical Review • Editor, Know: A Journal on the Formation of Knowledge • Editorial Board, Classical Philology • Editorial Board, The History and Theory of International Law, Oxford University Press • Editorial Board, Critical Analysis of Law • Editorial Board, L'Homme. Revue française d'anthropologie • Correspondant à l'étranger, Revue de l'histoire des religions EDUCATION • Ph.D., Classical Studies. University of Michigan, 1996 • B.A., Classics, summa cum laude. Princeton University, 1990 PRIZES, AWARDS AND NAMED LECTURES • Edmund G. Berry Lecture, University of Manitoba, 2018 • Sackler Lecturer, Mortimer and Raymond Sackler Institute of Advanced Studies, Tel Aviv University, 2017/2018 • Humanities Center Distinguished Visiting Scholar, University of Tennessee, 2017 • Elizabeth Battelle Clarke Legal History Colloquium, Boston University School of Law, 2017 • Maestro Lectures 2015, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan • Harry Carroll Lecture, Pomona College, March 2015 • Lucy Shoe Merritt Scholar in Residence, American Academy in Rome, 2014-2015 • Friedrich Wilhelm -

Horatius at the Bridge” by Thomas Babington Macauley

A Charlotte Mason Plenary Guide - Resource for Plutarch’s Life of Publicola Publius Horatius Cocles was an officer in the Roman Army who famously defended the only bridge into Rome against an attack by Lars Porsena and King Tarquin, as recounted in Plutarch’s Life of Publicola. There is a very famous poem about this event called “Horatius at the Bridge” by Thomas Babington Macauley. It was published in Macauley’s book Lays of Ancient Rome in 1842. HORATIUS AT THE BRIDGE By Thomas Babington Macauley I LARS Porsena of Clusium By the Nine Gods he swore That the great house of Tarquin Should suffer wrong no more. By the Nine Gods he swore it, And named a trysting day, And bade his messengers ride forth, East and west and south and north, To summon his array. II East and west and south and north The messengers ride fast, And tower and town and cottage Have heard the trumpet’s blast. Shame on the false Etruscan Who lingers in his home, When Porsena of Clusium Is on the march for Rome. III The horsemen and the footmen Are pouring in amain From many a stately market-place; From many a fruitful plain; From many a lonely hamlet, Which, hid by beech and pine, 1 www.cmplenary.com A Charlotte Mason Plenary Guide - Resource for Plutarch’s Life of Publicola Like an eagle’s nest, hangs on the crest Of purple Apennine; IV From lordly Volaterae, Where scowls the far-famed hold Piled by the hands of giants For godlike kings of old; From seagirt Populonia, Whose sentinels descry Sardinia’s snowy mountain-tops Fringing the southern sky; V From the proud mart of Pisae, Queen of the western waves, Where ride Massilia’s triremes Heavy with fair-haired slaves; From where sweet Clanis wanders Through corn and vines and flowers; From where Cortona lifts to heaven Her diadem of towers. -

STONEFLY NAMES from CLASSICAL TIMES W. E. Ricker

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Perla Jahr/Year: 1996 Band/Volume: 14 Autor(en)/Author(s): Ricker William E. Artikel/Article: Stonefly names from classical times 37-43 STONEFLY NAMES FROM CLASSICAL TIMES W. E. Ricker Recently I amused myself by checking the stonefly names that seem to be based on the names of real or mythological persons or localities of ancient Greece and Rome. I had copies of Bulfinch’s "Age of Fable," Graves; "Greek Myths," and an "Atlas of the Ancient World," all of which have excellent indexes; also Brown’s "Composition of Scientific Words," And I have had assistance from several colleagues. It turned out that among the stonefly names in lilies’ 1966 Katalog there are not very many that appear to be classical, although I may have failed to recognize a few. There were only 25 in all, and to get even that many I had to fudge a bit. Eleven of the names had been proposed by Edward Newman, an English student of neuropteroids who published around 1840. What follows is a list of these names and associated events or legends, giving them an entomological slant whenever possible. Greek names are given in the latinized form used by Graves, for example Lycus rather than Lykos. I have not listed descriptive words like Phasganophora (sword-bearer) unless they are also proper names. Also omitted are geographical names, no matter how ancient, if they are easily recognizable today — for example caucasica or helenica. alexanderi Hanson 1941, Leuctra. -

A Study of the Late Antique Latin Wedding Centos

INSTITUTIONEN FÖR SPRÅK OCH LITTERATURER DE INCONEXIS CONTINUUM A Study of the Late Antique Latin Wedding Centos DE INCONEXIS CONTINUUM A Study of the Late Antique Latin Wedding Centos SARA EHRLING QuickTime och en -dekomprimerare krävs för att kunna se bilden. SARA EHRLING DE INCONEXIS CONTINUUM INSTITUTIONEN FÖR SPRÅK OCH LITTERATURER DE INCONEXIS CONTINUUM A Study of the Late Antique Latin Wedding Centos SARA EHRLING Avhandling för filosofie doktorsexamen i latin, Göteborgs universitet 2011-05-28 Disputationsupplaga Sara Ehrling 2011 ISBN: 978–91–628–8311–9 http://hdl.handle.net/2077/24990 Distribution: Institutionen för språk och litteraturer, Göteborgs universitet, Box 200, 405 30 Göteborg Acknowledgements Due to diverse turns of life, this work has followed me for several years, and I am now happy for having been able to finish it. This would not have been possible without the last years’ patient support and direction of my supervisor Professor Gunhild Vidén at the Department of Languages and Literatures. Despite her full agendas, Gunhild has always found time to read and comment on my work; in her criticism, she has in a remarkable way combined a sharp intellect with deep knowledge and sound common sense. She has also always been a good listener. For this, and for numerous other things, I admire and am deeply grateful to Gunhild. My secondary supervisor, Professor Mats Malm at the Department of Literature, History of Ideas, and Religion, has guided me with insight through the vast field of literary criticism; my discussions with him have helped me correct many mistakes and improve important lines of reasoning. -

Hispellum: a Case Study of the Augustan Agenda*

Acta Ant. Hung. 55, 2015, 111–118 DOI: 10.1556/068.2015.55.1–4.7 TIZIANA CARBONI HISPELLUM: A CASE STUDY * OF THE AUGUSTAN AGENDA Summary: A survey of archaeological, epigraphic, and literary sources demonstrates that Hispellum is an adequate case study to examine the different stages through which Augustus’ Romanization program was implemented. Its specificity mainly resides in the role played by the shrine close to the river Clitumnus as a symbol of the meeting between the Umbrian identity and the Roman culture. Key words: Umbrians, Romanization, Augustan colonization, sanctuary, Clitumnus The Aeneid shows multiple instances of the legitimization, as well as the exaltation, of the Augustan agenda. Scholars pointed out that Vergil’s poetry is a product and at the same time the producer of the Augustan ideology.1 In the “Golden Age” (aurea sae- cula) of the principate, the Romans became “masters of the whole world” (rerum do- mini), and governed with their power (imperium) the conquered people.2 In his famous verses of the so-called prophecy of Jupiter, Vergil explained the process through which Augustus was building the Roman Empire: by waging war (bellum gerere), and by gov- erning the conquered territories. While ruling over the newly acquired lands, Augustus would normally start a building program, and would substitute the laws and the cus- toms of the defeated people with those of the Romans (mores et moenia ponere).3 These were the two phases of the process named as “Romanization” by histo- rians, a process whose originally believed function has recently been challenged.4 * I would like to sincerely thank Prof. -

Archiv Für Naturgeschichte

© Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zobodat.at Bericht über die wissenschaftlichen Leistungen auf dem Ciebiete der Arthropoden während der Jahre 1875 und 1876. Von Dr. Philipp Bertkau in Bonn, (Zweite Hälfte.) Hymenoptera. Gelegentlich seiner Abhandlung über das Riech Or- gan der Biene (s. oben 1876 p. 322 (114)) giebt Wolff p. 69 ff. eine sehr eingehende Darstellung der Mundwerk- zeuge der Hymenopteren, ihrer Muskeln u. s. w. Eine ver- ständliche Reproduction ohne Abbildung ist nicht möglich und muss daher hier unterbleiben; nur in Betreff des Saug- werkes der Biene lässt sich das Resultat der Untersuchung kurz angeben. Die Zunge ist nicht, wie vielfach behauptet worden ist, hohl, sondern an ihrer Unterseite nur bis zur Mitte ihrer Länge rinnig ausgehöhlt und von den erweiterten Rändern mantelartig umfasst. In dieser Rinne kann Flüssig- keit durch die blosse Capillarität in die Höhe steigen bis zu einer Stelle („Geschmackshöhle'O, die reichlich mit Nerven ausgestattet ist, die wahrscheinlich der Geschmacks- empfindung dienen. Zum Saugen stellen sich aber die verschiedenen Mundtheile (namentlich Unterlippe, Unter- kiefer mit ihren Tastern und Oberlippe mit Gaumensegel) zur Bildung eines Saug r obres zusammen, mit welchem die Flüssigkeiten durch die Bewegungen des Schlundes in diesen und weiter in den Magen befördert werden. Eine kürzere Mittheilung über Hymenopteren- ArcMv f. Naturg. XXXXIII. Jahrg. 2. Bd. P © Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zobodat.at 222 Bertkau: Bericht über die wissenschaftlichen Leistungen Bauten von Brischke enthält im Wesentliclien die An- gabe, dass ein Odynerums parietum seine Brutzellen in einem Federhalter angelegt habe. Schriften naturf. Ges. Danzig. Neue Folge III. -

Classical Mythology in the Victorian Popular Theatre Edith Hall

Pre-print of Hall, E. in International Journal of the Classical Tradition, (1998). Classical Mythology in the Victorian Popular Theatre Edith Hall Introduction: Classics and Class Several important books published over the last few decades have illuminated the diversity of ways in which educated nineteenth-century Britons used ancient Greece and Rome in their art, architecture, philosophy, political theory, poetry, and fiction. The picture has been augmented by Christopher Stray’s study of the history of classical education in Britain, in which he systematically demonstrates that however diverse the elite’s responses to the Greeks and Romans during this period, knowledge of the classical languages served to create and maintain class divisions and effectively to exclude women and working-class men from access to the professions and the upper levels of the civil service. This opens up the question of the extent to which people with little or no education in the classical languages knew about the cultures of ancient Greece and Rome. One of the most important aspects of the burlesques of Greek drama to which the argument turned towards the end of the previous chapter is their evidential value in terms of the access to classical culture available in the mid-nineteenth century to working- and lower- middle-class people, of both sexes, who had little or no formal training in Latin or Greek. For the burlesque theatre offered an exciting medium through which Londoners—and the large proportion of the audiences at London theatres who travelled in from the provinces—could appreciate classical material. Burlesque was a distinctive theatrical genre which provided entertaining semi-musical travesties of well-known texts and stories, from Greek tragedy and Ovid to Shakespeare and the Arabian Nights, between approximately the 1830s and the 1870s. -

New Latin Grammar

NEW LATIN GRAMMAR BY CHARLES E. BENNETT Goldwin Smith Professor of Latin in Cornell University Quicquid praecipies, esto brevis, ut cito dicta Percipiant animi dociles teneantque fideles: Omne supervacuum pleno de pectore manat. —HORACE, Ars Poetica. COPYRIGHT, 1895; 1908; 1918 BY CHARLES E. BENNETT PREFACE. The present work is a revision of that published in 1908. No radical alterations have been introduced, although a number of minor changes will be noted. I have added an Introduction on the origin and development of the Latin language, which it is hoped will prove interesting and instructive to the more ambitious pupil. At the end of the book will be found an Index to the Sources of the Illustrative Examples cited in the Syntax. C.E.B. ITHACA, NEW YORK, May 4, 1918 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. The present book is a revision of my Latin Grammar originally published in 1895. Wherever greater accuracy or precision of statement seemed possible, I have endeavored to secure this. The rules for syllable division have been changed and made to conform to the prevailing practice of the Romans themselves. In the Perfect Subjunctive Active, the endings -īs, -īmus, -ītis are now marked long. The theory of vowel length before the suffixes -gnus, -gna, -gnum, and also before j, has been discarded. In the Syntax I have recognized a special category of Ablative of Association, and have abandoned the original doctrine as to the force of tenses in the Prohibitive. Apart from the foregoing, only minor and unessential modifications have been introduced. In its main lines the work remains unchanged.