Policy Diffusion and Schenectady's Urban Redevelopment Alistair Phaup Union College - Schenectady, NY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

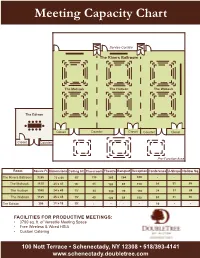

Meeting Capacity Chart

Meeting Capacity Chart Service Corridor The Rivers Ballroom The Mohawk The Hudson The Wabash The Edison Closet Counter Closet Counter Closet Closet Counter Pre-Function Area Room Square Ft. Dimensions Ceiling Ht. Classroom Theatre Banquet Reception Conference U-Shape Hollow Sq. The Rivers Ballroom 3285 73 x 45 15’ 135 365 264 330 - - - The Mohawk 1125 25 x 45 15’ 45 120 88 110 24 31 26 The Hudson 1080 24 x 45 15’ 45 120 88 110 24 31 26 The Wabash 1125 25 x 45 15’ 45 120 88 110 24 31 26 The Edison 399 21 x 19 15’ - - - - 10 - - FACILITIES FOR PRODUCTIVE MEETINGS: • 3700 sq. ft. of Versatile Meeting Space • Free Wireless & Wired HSIA • Custom Catering 100 Nott Terrace • Schenectady, NY 12308 • 518/393-4141 www.schenectady.doubletree.com Where the little things mean everything.TM DoubleTree by Hilton Schenectady, new york Begin your stay at DoubleTree by Hilton Hotel Schenectady with our delicious DoubleTree chocolate chip cookie, our welcome gift to you. Our downtown Schenectady hotel is a central cornerstone in this exciting and vibrant town and offers a convenient location just off Thruway 890. Easily accessible from Albany International Airport, the hotel is within walking distance to Proctors Theatre & Conference Facility and Union College. OUR HOTEL OFFERS: • 120 Guest Rooms • 3,700 Sq. Ft. of Function Space • Complimentary Wireless HSIA • 24-hour Fitness Center • LCD Flat Screen 32” HDTV • In-Room Dining • Full Business Center • On-site Restaurant and Bar 100 Nott Terrace Schenectady, NY 12308 AREA POINTS OF INTEREST For more information call 518/393-4141 • General Electric • Proctors Theatre • Siemens • Saratoga Springs Contact our sales team • Union College • Cooperstown Baseball Hall of Fame [email protected] • Rotterdam Square Mall • Stockade Historic District • Bow Tie Cinema Visit us online schenectady.doubletree.com Meeting Room Facilities & Services *Pricing varies based on number of overnight guest rooms and food & beverages requirements. -

PARTNER Fact Sheet – Union College 2021

PARTNER Fact sheet 2021/2022 Name of Institution UNION COLLEGE Contact Details : Head of the Institution David R. Harris Title President Address 807 Union Street Schenectady, NY 12308 Phone / Fax Phone: 518-388-6101/518-388-6066 Website www.union.edu Lara Atkins International Programs Office International Programs Office Director, International Programs Union College [email protected] Old Chapel, Third Floor Team members Schenectady, NY 12308 USA Ginny Casper Phone: 518-388-6002 Assistant Director, International Programs Fax: 518-388-7124 [email protected] 24-Hour Emergency Cell: 518-573-0471 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: www.union.edu/international Michelle Pawlowski Hours: M-F: 8:30 a.m. – 5 p.m. International Students Services Assistant Director, International Advising Location: Reamer 303 [email protected] Phone: (518) 388-8003 Fax: (518) 388-7151 Shelly Shinebarger Web: www.union.edu/is Director of Disability Services [email protected] Exchange Coordinators : Lara Atkins Contact(s) for Incoming Students Director, International Programs T : 518-388-6002 F : 518-388-7124 E : [email protected] Ginny Casper Contact(s) for Incoming Assistant Director, International Programs Students T : 518-388-6002 F : 518-388-7124 E : [email protected] Donna Sichak Contact(s) for Outgoing Students Assistant to the Directors, International Programs T : 518-388-6002 F : 518-388-7124 E : [email protected] Last modification: 16 November 2020 Page 1 / 4 Academic Information: 2021/2022 Application Term 1 (Fall) : Term 2 (Winter) : Term -

Schenectady Strategic Investment Plan

Schenectady Strategic Investment Plan CAPITAL REGION REDC December 2020 NEW YORK STATE DOWNTOWN REVITALIZATION INITIATIVE City of Schenectady Downtown Revitalization Initiative December 2020 Local Planning Committee (LPC) Members Gary McCarthy, Co-Chair Mayor - City of Schenectady David Buicko, Co-Chair The Galesi Group Mary D’Alessandro Stockade Neighborhood Mark Eagan Capital Region Chamber Ray Gillen Schenectady County Metroplex Development Authority David Harris Union College Robert Leonard Trustco Steady Moono SUNY Schenectady Phillip Morris Proctors Collaborative Maria Perreca Papa Little Italy Neighborhood Mitchell Ramsey Jay Street Stacey Rowland Rivers Casino & Resort Schenectady Mary Ann Ruscitto East Front Street Neighborhood Association Mike Saccocio City Mission of Schenectady Jim Salengo Downtown Schenectady Improvement Corp Marcy Steiner The Foundation for Ellis Medicine This document was developed by the Schenectady Local Planning Committee as part of the Downtown Revitalization Initiative and was supported by the NYS Department of State and NYS Homes and Community Renewal. The document was prepared by the following Consulting Team: With: • EDR • Ideas and Action • Karp Strategies • Middleton Construction • StreetSense • W-ZHA • Zimmerman/Volk Associates Unless otherwise noted, all images provided in this report were supplied by the Consulting Team, Metroplex Development Authority, or the City of Schenectady. Table of Contents Click on page numbers to jump to section. Foreword Executive Summary............................................................................. -

Schenectady DRI Application Was Held on May 23, 2019

REDC Region Capital Region Municipality Name City of Schenectady Downtown Name Downtown Schenectady County Name Schenectady Applicant Contact Schenectady Metroplex Ray Gillen, Chairman Email [email protected] Secondary Contact Jayme Lahut, Executive Director Contact Email [email protected] Schenectady is ready for the DRI. Our community works together to get results. In 2004, Schenectady was fading after the loss of 40,000 industrial jobs. Our downtown was arguably the most distressed in New York State. The fiscal situation was perilous. Today, fifteen years later, we have learned how to work together to produce impressive results. Our unified approach to economic development has resulted in new investments and new jobs that have turned around the city’s fortunes. From worst to first we like to say. We went from a negative financial outlook to solid bond ratings and four straight tax cuts. From an empty downtown to an urban center that is filled with jobs and life again. From a dead zone where a 60-acre abandoned factory site sat dormant for 50 years to a vibrant waterfront destination that is now the most visited place in the Capital Region. The vision for DRI Schenectady is to tie together our rebounding downtown with our new waterfront creating a dynamic 24/7 destination for businesses and visitors. We look forward to working with the Capital Regional Development Council to make this vision a reality. DRI planning and implementation resources are very much needed to complete the redevelopment of downtown Schenectady. A DRI investment will put our community on a firm, solid path toward a diversified economy with a strong 24/7 downtown. -

July 28,2010 ·Page 3 I Town·- Cons~Ltagj,;-·$Print Has Not.:Sh·Own· Need ~·Pt ;

12054 BETHLEHEM PUBLIC LIBRARY DO N0 T C I R CU lAT t;;·~::~;~;~ .......... FIRM • 'I ' Bf!THLEHI!M PUBLIC LIBRARY 451 DELAWARE AVE DELMAR NY 12054-3042 Tower talk continues 3042 Consultant says Sprint has not shown need t... ll·.. l;lll, ... t.l .. h.t •• ll·,ll. ... l •• l .. l.ll.l •• l See Page 3 In this ek's issue .., .... · • VOLUME Llll JULY 28, 2010 STARs and staff STARS (Seniors Teaching Reaching Out to Students} Attorney disappointed and Ravena-Coey School District members enjoyed an end · · in ·DA's decision •o·r-vear ice cream social event at •r.ll•nnonnlt's Jericho Drive-In on Soares drops criminal charges in that conclusion," Peter Gerstenzang, attor ney for homeowner Daniel Van Plew, said. ilillg-dorig~ditch incident; civil suit "Dan is very relieved .... We see the end is in See Page 15. not yet discussed with parents sight and he can get his life back." A I•. lawyer By CHARLES WIFF representing See 17•e Spotlight's view on [email protected] RobertMadeo, the matter on page 6 whose son was 1------.;_,;__..J A Delmar homeowner who was arrested visiting:a friend's house for a sleepover when after iillegedly tackling a teen playing "ding he and three other teens pulled the prank, dong ditch" will have the charges against said the very fact Soares himself handled the him dropped. minor charge is an indicator public opinion Peter Gerstenzang, aHorney for Daniel Van Plew, DA David Soares has decided not to pur held sway over the facts at hand. -

Download the Downtown Schenectady Visitor Guide &

herein with permission. with herein used Development Economic of Department State York New of trademark registered a is NY I ♥ state-of-the-art station is scheduled to be completed be to scheduled is station state-of-the-art and search “EV Destination” “EV search and 143 State Street, Schenectady, NY 12305 | 518-377-9430 | downtownschenectady.org | 518-377-9430 | 12305 NY Schenectady, Street, State 143 new a when 2018, late until available service limited and facilities Temporary • cityofschenectady.com For more information, visit visit information, more For • Maple Leaf routes Leaf Maple See this symbol on the map for locations: for map the on symbol this See Serving the Adirondack, Empire Service, Ethan Allen Express, Lake Shore Limited and and Limited Shore Lake Express, Allen Ethan Service, Empire Adirondack, the Serving • amenities. and attractions many downtown’s of distance walking charging stations that enable EV drivers to charge their vehicles within within vehicles their charge to drivers EV enable that stations charging 332 Erie Boulevard | 518-346-8651 | amtrak.com | 518-346-8651 | Boulevard Erie 332 Amtrak Station Amtrak (EV) vehicle electric of network a installed has Schenectady of City The BY TRAIN BY STATIONS STATIONS CHARGING EV Check website for routes and fares fares and routes for website Check • transportation public locations public Free on-street parking, weekdays after 6 p.m. and all weekend all and p.m. 6 after weekdays parking, on-street Free • The largest provider of intercity bus bus intercity of provider largest The • schedules available on buses and at many many at and buses on available schedules Paid parking at on-street meters and kiosks, weekdays 8 a.m.–6 p.m. -

Comprehensive Plan Schenectady County, New York

COMPREHENSIVE PLAN SCHENECTADY COUNTY, NEW YORK Last Revised April 8, 2021 Town of Duanesburg Comprehensive Plan Town of Duanesburg Vision Statement The Town of Duanesburg is a proud community of strong heritage and rural character. We encourage the preservation of our attractive and cultural landscape. We provide economically vibrant commercial and retail zones, and a variety of quality housing, cultural and recreational options. We are committed to sustaining our valuable economic and natural resources, particularly agricultural land use, open spaces, natural habitats, and fresh watersheds. We support thoughtful growth and development that enable affordable taxes, enhances the character of commercial and residential zones, improves our schools, and provides local business and employment opportunities. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Duanesburg Town Board Roger Tidball, Supervisor John Ganther, Deputy Supervisor and Council Member Francis R. Potter, Council Member Jeff Senecal, Council Member William Wenzel, Council Member Town Planning Board / Comprehensive Plan Update Committee Phill Sexton, Planning Board Chair and Comprehensive Plan Update Chair Jeffery Schmitt, Planning Board Vice Chair John Ganther, Deputy Town Supervisor Elizabeth Novak, Planning Board Member Michael Harris, Planning Board Member Joshua Houghton, Planning Board Member Martin Williams, Planning Board Member Thomas Rulison, Planning Board Member Nelson Gage, Zoning Board Chair Dale Warner, Town Planner and Building Inspector Terresa Bakner, Town Counsel 3 Table of Contents Introduction.......... -

Building Stones of Schenectady, New York

BUILDING STONES OF SCHENECTADY, NEW YORK JANET B. HOLLOCHER 2208 Barcelona Rd. Schenectady, NY 12309 KURT HOLLOCHER Geology Department Union College Schenectady, NY 12308 Introduction The building stones of downtown Schenectady contain some of the best examples of rock types and medium- and small-scale geologic features that the general public can readily view. Within easy walking or driving distance are high-quality rocks of many types, some of them carefully polished and beautifully displayed. There are buildings made with igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic rocks that include oxide rich gabbro, porphyritic granite, crossbedded sandstone, fossiliferous limestone, marble, gneiss, and partially melted migmatite. During this half-day trip, we will tour the downtown area to view the most interesting building stones, to see what minerals, fossils and other features they contain, to infer the geologic processes that formed them. The aim of this trip is to help people to learn more about geology, just by spending a few hours in downtown Schenectady (Figure 1). Anyone who is interested in geology can observe rock types and features on his own, without a guide, and without traveling miles on rural roads, bushwacking through woods and swamps, or stopping next to busy highways. Those who examine urban building stones can sharpen their powers of observation and learn to recognize a wide variety of rock types, minerals, features, and fossils. BRING HAND LENSES! Each block of building stone, or each panel of facing stone, is one small window into the past. However, there are some important things to remember when looking at building stones. First, remember that all of the rocks you are looking at came from somewhere else. -

Stockade Association Vol

IApril 2000 Published by The Stockade Association Vol. 41 No. 8 Stockade Calendar Spring Walks in the Stockade Future Dates Stones of the Stockade History and Architecture Mohawk Club Did you know that the Stockade Another self-guided walking Open House Dinner and downtown Schenectady contain tour of the Stockade that is now out Wed., Apr. 19, 7:00 PM some of the best examples of rock types and about was cooperatively developed ( see page 3 for details) and medium and small-scale geologic by Schenectady County Chamber of Secret Gardens of the features that the general public can read Commerce and Schenectady Heritage Stockade ily view? Area, with help from the Schenectady sponsored by the Friends Kurt Hollocher, from the Geology Historical Society and many others. of the Stockade Garden Department at Union College and his With an easy to follow format Group, June 23-24. Fri. 3 - wife, Janet have put together a self-guid and map, strollers can revisit our rich 8 PM, Sat. 10 AM - 4 PM ed walking tour. The tour highlights history, enjoy stories behind the examples of igneous, metamorphic, and facades, and learn architectural styles Stoop Beautification sedimentary rocks containing interesting and features. This is a great tour for Awards minerals, unusual textures, fossils and your out of town visitors. Criteria to be announced sedimentary features. This tour.-----------. SCHENECTADY'S in May The first Stockade stop is at the brochure is SlLf·GIJIDEO Park Clean-up Mohawk River wall at the bottom of available at Sat., May 20 Washington Avenue. These stone blocks Arthur's Market, Stockade are composed mostly of limestone The Chamber of Stockade Sidewalk Sale WalkingTour The second stop is at the The Commerce and Sat., June 3 First Reformed Church where in its the Heritage "ALCO: Its History and foundation you can see highly fossilfer Area Visitor Highlights" Speaker: ous limestone that contains abundant Center. -

CREDC the Capital Region Economic Development Council (CREDC) Is Accepting Applications from Qualified Applicants for the Downtown Revitalization Initiative (DRI)

DOWNTOWN REVITALIZATION INITIATIVE – CREDC The Capital Region Economic Development Council (CREDC) is accepting applications from qualified applicants for the Downtown Revitalization Initiative (DRI). Please refer to the attached Downtown Revitalization Initiative Guide for further information on the DRI program. Each applicant must complete this application and include the requested Appendices. Applicant responses for each section should be as complete and succinct as possible. Applications must be received by Empire State Development’s Capital Region Office by 4:00 p.m. on June 1, 2016. Applications are to be submitted by email to [email protected]. Files should be named in the following format: “Downtown_Municipality_Date”. If you have questions about the Downtown Revitalization Initiative, contact the ESD Capital Region Office at (518) 270-1130. BASIC INFORMATION Regional Economic Development Council (REDC) Region: Capital Region Municipality Name: Schenectady Downtown Name: Schenectady Arts, Entertainment and Technology District County: Schenectady Point of Contact: Ray Gillen Title: Chairman, Schenectady County Metroplex Development Authority Phone: 518-377-1109 ext. 1 Email: [email protected] Downtown Description: Provide an overview of the downtown and summarize the rationale behind nominating this downtown for a DRI award: Downtown Schenectady lost 25,000 jobs at GE during the 1980’s and 1990’s. No community in NYS was hit harder by the loss of jobs as a percent of total population. The core area of downtown was literally vacant and hollowed out by 2004 as a result of this massive job loss. A concerted, focused revitalization effort has been in place since 2004 resulting from a strong partnership between the City, County and the Metroplex Development Authority. -

President's Report

SCHENECTADY COUNTY COMMUNITY COLLEGE OUR COLLEGE – OUR FUTURE – The Strategic Plan to 2020 President’s Report December 2020 Expand Access and Increase Student Success The Office of Academic Affairs reports that as a part of the Strong Start to Finish (SSTF) grant, Instructor Cayla Gaworecki and Interim Dean Kelly Majuri attended the SUNY Placement Meeting on November 19. This recurring professional meeting has become a source of research, information, and networking as the Math Committee continues to reinforce our placement process as it relates to our new mathematics flow chart and our commitment to more immediate access to gateway mathematics courses for all of our students. CSTEP & LSAMP Director, Dr. Lorena Harris, and the CSTEP students sent out “Notes of Optimism” along with surprise gift bags to boost the morale of students in need during these difficult times. Interim Dean Eileen Abrahams and Division Secretary Elisabeth Gundlach called and emailed Fall 2020 students who had not yet registered for Spring 2021 classes. Overall, students appreciated the reminder and the personal phone calls. Interim Dean Eileen Abrahams produced two volumes of a new, campus-wide bulletin called The Lowdown, designed to inform adjunct and full-time faculty of upcoming events and deadlines. It will occasionally include relevant narrative, but its primary purpose is to keep faculty informed and up-to- date about issues such as ongoing registration efforts, final exam schedules, and Blackboard preparedness. This month, the Foundation received an additional -

Downtown Neighborhood Plan

Introduction Downtown Neighborhood Plan City of Schenectady Comprehensive Plan 2020 Reinventing the City of Invention Brian U. Stratton Mayor DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT Schenectady 2020 Introduction Comprehensive Plan The Downtown neighborhood plan is being developed as part of the City of Schenectady Vision Plan 2020 – the city’s first Comprehensive Plan since 1971. Nine residential neighborhood plans have been developed as well as this downtown strategy, a policy-oriented city-wide plan and a series of catalyst projects. In addition, the City is revising its zoning ordinance and other land management tools. Each neighborhood strategy outlines the goals and policies and recommends changes in land use which will guide future livability of the neighborhood. Located in the central portion of the City, the Downtown neighborhood encompasses approximately 340 acres. Nott Street serves as the northern boundary. Lenox Road and Nott Terrace serves as the eastern boundary. The City line and the Mohawk River (excluding the Stockade Partnerships with Neighborhood) serve as the western boundary of the Downtown. The southern boundary of this neighborhood includes portions of Union Avenue and Broadway. Metroplex Development Authority are critical to Community and institutional uses located in the neighborhood include City Hall, County Office downtown’s revitalization Building, Post Office, the main branch of the Library, Amtrak Station, central business district, and Proctor’s Theatre. Erie Boulevard, State Street, and Broadway are the major roadways of the and the establishment of neighborhood. an exciting retail and entertainment district. Downtown Neighborhood Plan DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT 1 Schenectady 2020 Demographics Comprehensive Plan According to the 2000 Census, the Downtown neighborhood has a residential population of 3,915 mostly located in the East Front Street and College Park areas.