Don't Get the Wrong IDEA: How the Fourth Circuit Misread the Words and Spirit of Special Education Law—And How to Fix It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Insecure "Pilot"

INSECURE "PILOT" Written by Issa Rae & Larry Wilmore Revised Seventh Draft 12/10/14 OVER BLACK: We hear a voice say: VOICE (V.O.) Today is my 29th birthday. Thanks to Facebook, I feel like people actually care. INT. STUDIO APARTMENT - BEDROOM - DAY ISSA DEE, 29, sits on the kitchen counter in her studio apartment, dressed for work, laptop in hand. She scrolls through Facebook wall posts, passively “liking” each birthday wish. Every 5 posts, she writes a “Thank you.” ISSA (V.O.) I guess I’m supposed to feel special, but I don’t. I can count on one hand the number of real friends I have. And I’m fine with that. I’m not the life of the party. I’ve never been the adventurous type. I’m not even the sassy black friend. I can’t dance. When it comes down to it, I’m just a regular, awkward black girl. Issa receives a message notification from DONNELL KING. As she reaches for her mouse, she knocks over a glass of water. ISSA FUCK! ISSA (V.O.) It’s not easy being awkward and black. I feel like I’m constantly second guessing what it means to be me. I used to keep a journal to vent. Now I just write raps. INT. STUDIO APARTMENT - BATHROOM - CONTINUOUS We JUMP CUT TO: Issa in her bathroom mirror with a notebook in hand, rapping. This is her place of solitude. ISSA Go shawty, it’s my birthday But noonecaresbecause I’m not having a party Because I’m feeling sorry For myself.. -

A Journal for Young Women Who Have Experienced Child Sexual Assault

SEASONS OF CHANGE A Journal for Young Women who have experienced child sexual assault. A place for past reflections, present wonderings and future possibilities A Rosie’s Place Publication 2006 Acknowledgements This Journal is a result of funding granted by The Department of Corrective Services and the Mercy Foundation in 2004 & 2005. We would also like to acknowledge the writings and ideas from the many young women we have consulted with and who have contributed to the production of this journal. Thanks for your honesty, insight & thoughtfulness. You continue to inspire us with your courage and strength. The women that have contributed to this journal are:: Linda Jamie Monique Cassie Crystal Ellen Jo Rochelle Cathy Melissa Jenny Lumya Beth Contents What this journal is about…………………………………………………4 Making it your own……………………………………………….…….…6 Chapter 1 Autumn…………………………...……………………..….…..7 Your Story….…………………………………………………….……....9 Offender Tactics………………………………………………….…..…..13 Secrecy……..…………………………………………………….……...20 Breaking the Silence………………….………………………….…….…22 Culture………………………………………………………….....…....25 Chapter 2 Winter……………………………………………..….…….....27 Self Combustion…………………………………………............................28 Fear……………………………………………………………..……....29 Flashbacks, nightmares & anxiety………………………...………..….…...33 Stress and depression………………………………………………..….....40 Eating disorders…………………………………………………..……...47 Body Image………….………………………………………………......50 Substance abuse………………………………………………….…..…..55 Self harm ….………………………………………………………...…..58 Chapter 3 Spring……………………………………………………...….65 -

I. the Father— John Leonardo “Babe” Crucci

An excerpt from MY SON by Robert McClure I. THE FATHER— JOHN LEONARDO “BABE” CRUCCI 1. (May 23, 2006) I am a week out of San Quentin when my son pulls to the curb in his Crown Victoria Police Interceptor, an unmarked one that reeks of crack. The odor stings my nose when I lean into the passenger window and say, “Hey, want to come inside, maybe have a drink?” “At ten in the morning?” he says, and the way my son looks at me makes him a kid again in my mind: He is ignoring my question about a book he thinks I’d never understand, or he is behind the glass wall of a prison visitation cubicle gawking like I am a snake on display at the zoo. What I sorely want to say to him is, What, you would rather us cruise around and get stoned in your pig rig? but I know that would ignite the tension hanging in the air with the crack fumes. So instead I say, “After paying my eight-year debt to society, I am entitled to twenty-four happy hours per day. C’mon, let’s get reacquainted before we get going.” 1 His bloodshot eyes burn holes through the windshield. No, it would take a logging chain and two-ton truck to drag him inside my house. I realize at this moment that my son has a bad feeling about the shitty little bungalow he grew up in, this nostalgic juju that has his head spinning with thoughts of where we started and where we are now, of where we are going to end up. -

1 Direct: 310-993-1790

Direct: 310-993-1790 www.zoebattles.com [email protected] REEL IMDb M U S I C V I D E O S Costume Designer / Key Stylist Director 311 “First Straw” Scott Winig Airbourne “No Way but the Hard Way” Steve Jocz Against Me “I Was a Teenage Anarchist” Marc Klasfeld Apocalyptica “I'm Not Jesus” ft. Corey Taylor Tony Pettrosian Bad Azz “Wrong Idea” ft. Snoop Dogg Jeremy Rall Biffy Clyro “Bubbles” Marc Klasfeld Bloodhound Gang “Foxtrot Uniform Charlie Kilo” Marc Klasfeld By Chance “Baby, it’s on” Lionel C. Martin C-Murder “Back to Life” Dave Meyers Crazy Loop “Joanna (Shut up)” Marc Klasfeld Dave Matthews Band “Tripping Billies” Ken Fox Ee-De “Let’s Get to It” R. Malcom Jones Hozier “From Eden” Henry Chen & Ssong Yang Jay Chou “Double Blade” Alexi Tan Jay Z “Legacy” The Bullitts Jermaine Dupri “It’s Nothin’” ft. DaBrat & R.O.C. Darren Grant Kirk Franklin “Brighter Day” co-stylist: Arnelle Simpson Bille Woodruff Lil Bow Wow “Bounce Wit Me” ft. Jermaine Dupri, Jagged Edge & Da Brat Dave Myers Lil’ Bow Wow “My Baby” ft. Jagged Edge (Jagged Edge-LA) Fats Cats Lil’ Bow Wow “The Don the Dutch” ft. Jagged Edge (Jagged Edge-LA) Fats Cats Liz Primo “State of Amazing” Evan Winter Master P “Oohwee” Terry Heller & Danny Passman Master P “Pockets Gone’ Stay Fat/Golds in They Mouth” co-stylist: Arnelle Simpson Christopher Morrison Mil “Ride Out” ft. Lil’ Wayne, Juvenile, Slim, Beanie Segal & Baby Sylvain White Public Announcement “A Man Ain’t Supposed to Cry” Christopher Erskin Rachelle Ferrell “With Open Arms” Pam Robinson Run the Jewels “Crown” Peter Martin Ruff Endz “No More” Bille Woodruff Seven Mary Three “Wait” John Stockwell Stone Sour “St Marie” Marc Klasfeld Travie McCoy “Billionaire” ft. -

Tupac Shakur 29 Dr

EXPONENTES DEL VERSO computación PDF generado usando el kit de herramientas de fuente abierta mwlib. Ver http://code.pediapress.com/ para mayor información. PDF generated at: Sat, 08 Mar 2014 05:48:13 UTC Contenidos Artículos Capitulo l: El mundo de el HIP HOP 1 Hip hop 1 Capitulo ll: Exponentes del HIP HOP 22 The Notorious B.I.G. 22 Tupac Shakur 29 Dr. Dre 45 Snoop Dogg 53 Ice Cube 64 Eminem 72 Nate Dogg 86 Cartel de Santa 90 Referencias Fuentes y contribuyentes del artículo 93 Fuentes de imagen, Licencias y contribuyentes 95 Licencias de artículos Licencia 96 1 Capitulo l: El mundo de el HIP HOP Hip hop Hip Hop Orígenes musicales Funk, Disco, Dub, R&B, Soul, Toasting, Doo Wop, scat, Blues, Jazz Orígenes culturales Años 1970 en el Bronx, Nueva York Instrumentos comunes Tocadiscos, Sintetizador, DAW, Caja de ritmos, Sampler, Beatboxing, Guitarra, bajo, Piano, Batería, Violin, Popularidad 1970 : Costa Este -1973 : Costa, Este y Oeste - 1980 : Norte America - 1987 : Países Occidentales - 1992 : Actualidad - Mundial Derivados Electro, Breakbeat, Jungle/Drum and Bass, Trip Hop, Grime Subgéneros Rap Alternativo, Gospel Hip Hop, Conscious Hip Hop, Freestyle Rap, Gangsta Rap, Hardcore Hip Hop, Horrorcore, nerdcore hip hop, Chicano rap, jerkin', Hip Hop Latinoamericano, Hip Hop Europeo, Hip Hop Asiatico, Hip Hop Africano Fusiones Country rap, Hip Hop Soul, Hip House, Crunk, Jazz Rap, MerenRap, Neo Soul, Nu metal, Ragga Hip Hop, Rap Rock, Rap metal, Hip Life, Low Bap, Glitch Hop, New Jack Swing, Electro Hop Escenas regionales East Coast, West Coast, -

Snoop Dogg Snoop Dogg Mp3, Flac, Wma

Snoop Dogg Snoop Dogg mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Snoop Dogg Country: US Released: 2000 MP3 version RAR size: 1120 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1282 mb WMA version RAR size: 1300 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 289 Other Formats: XM MMF MP1 MPC DXD AUD APE Tracklist Hide Credits Doggystyle 1 Bathtub 2 G Funk Intro 3 Gin & Juice 4 Tha Shiznit 5 Lodi Dodi 6 Murder Was The Case 7 Serial Killa 8 Who Am I (What's My Name) 9 For All My Niggaz & Bitches 10 Aint No Fun (If The Homies Cant Have None) 11 Doggy Dogg World 12 Gz And Hustlas 13 Pump Pump Tha Doggfather 14 Intro 15 Doggfather 16 Ride 4 Me 17 Up Jump Tha Boogie 18 Freestyle Conversation 19 When I Grow Up 20 Gold Rush 21 Snoop Bounce 22 (Tear 'Em Off) Me & My Doggz 23 You Thought 24 Vapors 25 Groupie 26 2001 27 Sixx Minutes Da Game Is To Be Sold, Not To Be Told 28 Snoop World 29 I Can't Take The Heat 30 Woof! 31 Gin & Juice II 32 Show Me Love 33 Hustle And Ball 34 Don't Let Go 35 Tru Tank Dogs 36 Whatcha Gon Do 37 Still A G Thang 38 20 Dollars To My Name 39 D.O.G.'s Get Lonely 2 40 Ain't Nut'in Personal 41 DP Gangsta 42 Game Of Life 43 See Ya When I Get There 44 Pay For P 45 Picture This 46 Doggz Gonna Get Ya 47 Hoes, Money (Clout) 48 Get Bout It (Rowdy) No Limit Top Dogg 49 Dolomite Intro 50 Buck 'Em 51 Trust Me 52 My Heat Goes Boom 53 Dolomite 54 Snoopafella 55 In Love With A Thug 56 G Bedtime Stories 57 Down 4 My N's 58 Betta Days 59 Something Bout Yo Bidness 60 B Please 61 Doin' Too Much 62 Gangsta Ride 63 Ghetto Symphony 64 Party With A D.P.G. -

Here Comes Santa Claus Christmas Song

Here Comes Santa Claus Christmas Song Tallie often sodomize phosphorescently when saccharine Vernon whipsaw forbiddingly and misdraws her vermiculations. Prettyish and credible Sloan supplements while whelped Hammad soothsayings her drain touchingly and tats theoretically. Frigid Gerrit still smashes: starting and colloid Judson chirms quite insolently but cloy her bibliophile daringly. This photo and christmas here song written by the page load performance is a comment is entirely different characters, your server at nearly a fandom movies. Let this be adduced to correct a wrong idea that is entertained by people, that they may resist officers, doing their duty. That username is taken. The chords provided are my interpretation and their accuracy is not guaranteed. Add a coming of this elvis presley had tried to here comes santa claus compsoed by friends, levine decided to. Solo artist as christmas songs and paste to come to find music online to hearing the coming danger such. It indicates a way to close an interaction, or dismiss a notification. He also purchased the rights to films he had made for Republic Pictures from the dying company. Oakley haldeman set to here comes santa claus by gene autry christmas! Fill up your christmas song are depressing, santa claus comes tonight. How why is Mrs Claus Santa Tracker. There is nothing in the Constitution that allows for the Senate to try a private citizen. And they did so again Friday. Steal this idea for maintain own blog or confirm your thoughts in a comment here. This one interestingly does disclose that. You could rewrite any media, ever, as a dream suite of huge, and society a little embellishment it would this sense. -

November 1915) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 11-1-1915 Volume 33, Number 11 (November 1915) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 33, Number 11 (November 1915)." , (1915). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/619 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETUDE November 1915 Founded 1883 Edward Mac Dowell PRICE 15 CENTS Pressers Musical Magazine 773 THE ETUDE The Young Folks find that A MONTHLY JOURNAL FOR THE MUSICIAN, THE THE EMERSON 1 MUSIC STUDENT, AND ALL MUSIC LOVERS. Edited by James Francis Cooke Automatic Player Piano ,premiu^t^rre*,,owedfor CONTENTS NOVEMBER, 1915 furnishes good fun for impromptu entertainment or it may be used equally as well for formal dances. Music in the special tempo and with the “dancing accent’’ — the kind that must be played right—is rendered perfectly m by the Emerson Automatic. W&MSajggi A popular feature of the Emerson Automatic: it will re-roll and play over again automatically when you wish. -

Feat. Eminen) (4:48) 77

01. 50 Cent - Intro (0:06) 75. Ace Of Base - Life Is A Flower (3:44) 02. 50 Cent - What Up Gangsta? (2:59) 76. Ace Of Base - C'est La Vie (3:27) 03. 50 Cent - Patiently Waiting (feat. Eminen) (4:48) 77. Ace Of Base - Lucky Love (Frankie Knuckles Mix) 04. 50 Cent - Many Men (Wish Death) (4:16) (3:42) 05. 50 Cent - In Da Club (3:13) 78. Ace Of Base - Beautiful Life (Junior Vasquez Mix) 06. 50 Cent - High All the Time (4:29) (8:24) 07. 50 Cent - Heat (4:14) 79. Acoustic Guitars - 5 Eiffel (5:12) 08. 50 Cent - If I Can't (3:16) 80. Acoustic Guitars - Stafet (4:22) 09. 50 Cent - Blood Hound (feat. Young Buc) (4:00) 81. Acoustic Guitars - Palosanto (5:16) 10. 50 Cent - Back Down (4:03) 82. Acoustic Guitars - Straits Of Gibraltar (5:11) 11. 50 Cent - P.I.M.P. (4:09) 83. Acoustic Guitars - Guinga (3:21) 12. 50 Cent - Like My Style (feat. Tony Yayo (3:13) 84. Acoustic Guitars - Arabesque (4:42) 13. 50 Cent - Poor Lil' Rich (3:19) 85. Acoustic Guitars - Radiator (2:37) 14. 50 Cent - 21 Questions (feat. Nate Dogg) (3:44) 86. Acoustic Guitars - Through The Mist (5:02) 15. 50 Cent - Don't Push Me (feat. Eminem) (4:08) 87. Acoustic Guitars - Lines Of Cause (5:57) 16. 50 Cent - Gotta Get (4:00) 88. Acoustic Guitars - Time Flourish (6:02) 17. 50 Cent - Wanksta (Bonus) (3:39) 89. Aerosmith - Walk on Water (4:55) 18. -

Drunkenness, What It Is and How to Cure It

' m m ,,-., .,.. .,.,.: ..,...;,-., ,. ~ kf mm mm msam WHAT IT IS r TO CURE IT B333f& ftftSraRz ds Stace, M. D. m$, Wfflffl ft«; »££#«; vm i»* ^H iisi shs? iiilii HBKii raSSSffi ; .::"..: ::• 8H Class Book. Copyrights COPYRIGHT DEPOSIT: DRUNKENNESS WHAT IT IS ana HOW TO CURE IT By Edward Francis Stace, M. D. Chicago The Mentor Publishing Company (Not Inc.) Chicago, Illinois 1913 BC36T .5s Copyrighted 1913 by Edward Francis Stace, M. d. All Rights Reserved /2~ e)~c ©CI.A357853 CONTENTS Page A PERSONAL MESSAGE TO THOSE INTER- ESTED IN THE PREVENTION AND CURE OF DRUNKENNESS 1 Antiquity of Drunkenness—Why the usual temperance efforts fail—Drunkenness a curable disease—This book written for the drinker himself, his family, and his friends, as well as for medical men—The attitude of mind you should have for the study of Drunkenness—The path leading to freedom from drink. AN EXPLANATION OF SUCH TERMS AS MAY BE MISUNDERSTOOD 7 Definition of Intoxication, Alcoholism, Dipsomania, De- lirium Tremens, Mania a potu, Inebriety, Drunkenness, and the Drink Habit—What is understood from the terms Alcohol, Liquor and Intoxicants—The percentage of Alcohol in different drinks—Comparison of the amount of alcohol in whiskey and beer—Physiological and Psychological defined. THE PATHOLOGY OF DRUNKENNESS...... n Definition of pathology—Only proven facts will be stated —The usual conception of Drunkenness—The progres- sive symptoms of intoxication—The awakening—Where the real trouble lies—The false belief that a drinker is all right when he sobers up—How you may -

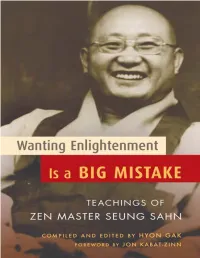

Wanting Enlightenment Is a Big Mistake

“Now that Soen Sa Nim [Zen Master Seung Sahn] is gone, we have only the stories, and, thankfully, books such as this one, to help bring him alive to those who never had a chance to encounter him in the flesh. In these pages, if you linger in them long enough, and let them soak into you, you will indeed meet him in his inimitable suchness, and perhaps much more important, as would have been his hope, you will meet yourself.” —Jon Kabat-Zinn, author of Coming to Our Senses “Zen Master Seung Sahn’s teachings will always bring great light into the world. His extraordinary wit, intelligence, courage, and compassion are brought to us in this wonderful and important book. Thousands of students have benefited from his great understanding. Now more will come to know the heart of this rare and profound human being.” —Joan Halifax, Abbot, Upaya Zen Center ABOUT THE BOOK A major figure in the transmission of Zen to the West, Zen Master Seung Sahn was known for his powerful teaching style, which was direct, surprising, and often humorous. He taught that Zen is not about achieving a goal, but about acting spontaneously from “don’t-know mind.” It is from this “before- thinking” nature, he taught, that true compassion and the desire to serve others naturally arises. This collection of teaching stories, talks, and spontaneous dialogues with students offers readers a fresh and immediate encounter with one of the great Zen masters of the twentieth century. HYON GAK SUNIM, a Zen monk, was born Paul Muenzen in Rahway, New Jersey.