Turkish Delight, Twelfth Night, and the Problem of Susan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by C.S Lewis. Introduction

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by C.S Lewis. Introduction Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy Pevensie are four siblings sent to live in the country with the eccentric Professor Kirke during World War II. The children explore the house on a rainy day and Lucy, the youngest, finds an enormous wardrobe. Lucy steps inside and finds herself in a strange, snowy wood. Lucy encounters the Faun Tumnus, who is surprised to meet a human girl. Tumnus tells Lucy that she has entered Narnia, a different world. Tumnus invites Lucy to tea, and she accepts. Lucy and Tumnus have a wonderful tea, but the faun bursts into tears and confesses that he is a servant of the evil White Witch. The Witch has enchanted Narnia so that it is always winter and never Christmas. Tumnus explains that he has been enlisted to capture human beings. Lucy implores Tumnus to release her, and he agrees. Lucy exits Narnia and eagerly tells her siblings about her adventure in the wardrobe. They do not believe her, however. Lucy's siblings insist that Lucy was only gone for seconds and not for hours as she claims. When the Pevensie children look in the back of the wardrobe they see that it is an ordinary piece of furniture. Edmund teases Lucy mercilessly about her imaginary country until one day when he sees her vanishing into the wardrobe. Edmund follows Lucy and finds himself in Narnia as well. He does not see Lucy, and instead meets the White Witch that Tumnus told Lucy about. The Witch Witch introduces herself to Edmund as the Queen of Narnia. -

The Great War and Narnia: C.S. Lewis As Soldier and Creator

Volume 30 Number 1 Article 8 10-15-2011 The Great War and Narnia: C.S. Lewis as Soldier and Creator Brian Melton Liberty University in Lynchburg, VA Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Melton, Brian (2011) "The Great War and Narnia: C.S. Lewis as Soldier and Creator," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 30 : No. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol30/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Looks at influence of orldW War I in Lewis’s autobiography and on war in Narnia, correcting mistaken search by some critics for deep-seated war trauma in Lewis’s life. Reinforces that Lewis and Tolkien were not psychological twins, had differing personalities going into the war, and came out of it with different approaches to dealing with war in their fiction. -

The Horse and His Boy

Quick Card: The horse and his boy The Horse and His Boy, by C. S. Lewis. Reference ISBN: 9780007588541 Shasta, a Northerner enslaved to a Calormene fisherman, dreams of escape to the free North of Archenland. With the help of a talking horse named Bree, Shasta flees, meeting another pair of fugitives along the way: Plot Aravis and her talking horse Hwin. As they journey northwards, the four uncover a plot by Rabadash, the prince of Calormene, to conquer Archenland and threaten the peace of the northern lands. They race to warn the Archenlanders and rally the Narnians to their aid. This story is set during the Golden reign of the Pevensie children: Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy. Calormene- A land South of Narnia, it is home to cruel, pagan slave lords: the Tarquins. Setting Narnia- Home of the four kings and queens of legend and kingdom of the lion Aslan, the Son of the King Beyond the Sea. Archenland- Borderland between Calormene and Narnia, populated by free people whose loyalty is to Narnia and Aslan. Shasta- The protagonist of the piece is a young boy, uneducated and neglected. Though he is immature, he has an inbred longing for freedom and justice and an indomitable hope to escape to the free North. Bree recognizes at once that he must be “of true Northern stock.” Bree- Pompous and self-important, the Narnian horse brags about his knowledge of the North and plays the courageous war-horse though he is really a coward at heart. Despite his boorish tone, he is a loyal friend. -

The Shifting Perils of the Strange and the Familiar’: Representations of the Orient in Children's Fantasy Literature

‘The shifting perils of the strange and the familiar’: representations of the Orient in children's fantasy literature by Farah Ismail Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magister Artium (English) In the Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria Pretoria 2010 Supervisor: Ms. Molly Brown © University of Pretoria Acknowledgments I would like to thank: Ms. Molly Brown, for her guidance and support My parents, Suliman and Faaiqa Ismail, for their support and encouragement Mrs Idette Noomé, for her help with the Afrikaans translation of the summary Yvette Samson, whose boundless enthusiasm has been an immense inspiration © University of Pretoria Summary This thesis investigates the function of representations of the Orient in fantasy literature for children with a focus on The Chronicles of Narnia as exemplifying its most problematic manifestation. According to Edward Said (2003:1-2), the Orient is one of Europe’s ‘deepest and most recurring images of the Other… [which]…has helped to define Europe (or the West) as its contrasting image, idea, personality, experience.’ However, values are grouped around otherness1 in fantasy literature as in no other genre, facilitating what J.R.R. Tolkien (2001:58) identifies as Recovery, the ‘regaining of a clear view… [in order that] the things seen clearly may be freed from the drab blur of triteness or familiarity.’ In Chapter One, it is argued that this gives the way the genre deals with spaces and identities characterized as Oriental, which in Western stories are themselves vested with qualities of strangeness, a peculiar significance. Specifically, new ways of perceiving the function of representations of the Other are explored in the genre of fantasy. -

The Lion, the Witch & the Wardrobe

THE LION, show time THE WITCH for & THE WARDROBE Teachers based on the novel by c.s.lewis Welcome to Show Time, a performance resource guide published for the CSB/SJU Fine Arts Education Series. This edition of Show Time is designed to be used before or after a perform- ance of The Lion,The Witch & The Wardrobe. Suggested activities in this issue include social studies and language arts connections designed to be adapted to your time and needs. Check out Show Time for Students, a one-page, student-ready 6+1 Trait writ- ing activity for independent or group learners. Please feel free to make copies of pages in this guide for student use. How May We Help You ? Story Synopsis 1 Meet the Characters 2 Social Studies 3 Turkish Delight 4 Language Arts 5 Show Time for Students 6 Bibliography 7 Presented by TheatreWorks/USA Theater Etiquette 8 1 1 STORY SYNOPSIS This musical production is based on the novel The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe written by C.S. Lewis and published in 1950. Setting: England in World War II The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is a musical about four siblings; Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy Pevensie who are sent to live musical-a play that tells in the country with their Uncle Digory its story using dialog during the bombing of London. and songs. Lucy discovers a magic ward- robe in her uncle’s home and upon wardrobe-a large cup- board style closet used stepping inside she finds herself in a to store clothing. -

We Produce the Unique Flavor Real Turkish Delight of Unforgettable Moments, Özdilek Lokum, for You

Real Turkish Delight We produce the unique flavor Real Turkish Delight of unforgettable moments, Özdilek Lokum, for you. One of our traditional flavors dating back to the 15th century, the Turkish delight started to be produced in our facilities in Afyonkarahisar in 1996 with the Özdilek Lokum brand. Produced with different flavors, the traditional handiwork method and devotion, Özdilek Lokum meets its customers in Özdilek hypermarkets. And the special boutique products prepared by the Özdilek Holding Food R&D unit are presented to the customers in Özdilek Turkish Delight stores in Özdilek Bursa and ÖzdilekPark İstanbul ÖZDİLEK LOKUM WICK SERIES Wits its orange and pomegranate flavored varieties, Özdilek Lokum turns the Turkish delight into a fresh sweet and offers a kadayif and pistachio dipped wick Turkish delight for those looking for a more traditional flavor. As well as the plain pistachio that offers you pistachio’s harmony with the Turkish delight, you can also choose the milk pistachio wick Turkish delight for its smooth and milky taste. ORANGE PISTACHIO TURKISH DELIGHT | POMEGRANATE PISTACHIO TURKISH DELIGHT PLAIN PISTACHIO TURKISH DELIGHT | MILK PISTACHIO TURKISH DELIGHT KADAYIF PISTACHIO TURKISH DELIGHT ÖZDİLEK LOKUM HONEY SERIES Özdilek Lokum honey series, prepared with honey, which is considered as a remedy from past to present, have the feeling of the Ottoman court kitchen. Özdilek honey Turkish delights offer a unique delicacy, appealing to all tastes with hazelnut, almond and pistachio kadayif varieties. Freshly produced, Özdilek Turkish delights will enrich your presentations with five various series! HAZELNUT-DIPPED HONEY & HAZELNUT TURKISH DELIGHT HONEY ALMOND TURKISH DELIGHT HONEY, PISTACHIO & KADAYIF TURKISH DELIGHT ÖZDİLEK LOKUM SQUARE CLASSICS SERIES Classic Turkish delight series, the favorite of those who prefer simpler flavors, offer alternatives as rose & biscuit, lemon and mint. -

An Introduction to Narnia - Part II: the Geography of the Chronicles

Volume 2 Number 3 Article 5 Winter 1-15-1971 An Introduction to Narnia - Part II: The Geography of the Chronicles J. R. Christopher Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Christopher, J. R. (1971) "An Introduction to Narnia - Part II: The Geography of the Chronicles," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 2 : No. 3 , Article 5. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol2/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Part two is an overview of the geography of Narnia based on textual clues and maps. Speculates on the meaning of the geography in theological and metaphysical terms. Additional Keywords Lewis, C.S. Chronicles of Narnia—Geography This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. -

Tören Yemeklerġnġn Bġlġnġrlġğġ Üzerġne Kuġaklar Arasindakġ Farkliliklarin Belġrlenmesġne Yönelġk Bġr Araġti

TÖREN YEMEKLERĠNĠN BĠLĠNĠRLĠĞĠ ÜZERĠNE KUġAKLAR ARASINDAKĠ FARKLILIKLARIN BELĠRLENMESĠNE YÖNELĠK BĠR ARAġTIRMA: AFYONKARAHĠSAR ĠLĠ ÖRNEĞĠ Nazmiye ÇĠFTÇĠ Yüksek Lisans Tezi DanıĢman: Dr.öğr.Üyesi Asuman PEKYAMAN Haziran, 2019 Afyonkarahisar T.C. AFYON KOCATEPE ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ SOSYAL BĠLĠMLER ENSTĠTÜSÜ TURĠZM ĠġLETMECĠLĠĞĠ ANABĠLĠM DALI YÜKSEK LĠSANS TEZĠ TÖREN YEMEKLERĠNĠN BĠLĠNĠRLĠĞĠ ÜZERĠNE KUġAKLAR ARASINDAKĠ FARKLILIKLARIN BELĠRLENMESĠNE YÖNELĠK BĠR ARAġTIRMA: AFYONKARAHĠSAR ĠLĠ ÖRNEĞĠ Hazırlayan Nazmiye ÇĠFTÇĠ DanıĢman Dr.Öğr.Üyesi Asuman PEKYAMAN AFYONKARAHĠSAR-2019 YEMĠN METNĠ Yüksek Lisans tezi olarak sunduğum „‟Tören Yemeklerinin Bilinirliği Üzerine KuĢaklar Arasındaki Farklılıkların Belirlenmesine Yönelik Bir AraĢtırma: Afyonkarahisar Ġli Örneği” adlı çalıĢmanın, tarafımdan bilimsel ahlak ve geleneklere aykırı düĢecek bir yardıma baĢvurmaksızın yazıldığını ve yararlandığım eserlerin Kaynakça‟da gösterilen eserlerden oluĢtuğunu, bunlara atıf yapılarak yararlanmıĢ olduğumu belirtir ve bunu onurumla doğrularım. 14.05.2019 Nazmiye ÇĠFTÇĠ ii TEZ JÜRĠSĠ KARARI VE ENSTĠTÜ MÜDÜRLÜĞÜ ONAYI iii ÖZET TÖREN YEMEKLERĠNĠN BĠLĠNĠRLĠĞĠ ÜZERĠNE KUġAKLAR ARASINDAKĠ FARKLILIKLARIN BELĠRLENMESĠNE YÖNELĠK BĠR ARAġTIRMA: AFYONKARAHĠSAR ĠLĠ ÖRNEĞĠ Nazmiye ÇĠFTÇĠ AFYON KOCATEPE ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ SOSYAL BĠLĠMLER ENSTĠTÜSÜ TURĠZM ĠġLETMECĠLĠĞĠ ANABĠLĠM DALI Haziran 2019 DanıĢman: Dr.Öğr.Üyesi Asuman PEKYAMAN Zengin mutfak kültürüne ve yemek çeĢitliliğine sahip Afyonkarahisar‟da sürdürülen geleneğin bir parçası olarak doğum, ölüm, sünnet, evlilik gibi özel günlerde -

Trncfjanti NG THT I MAG I NATION

trNCFJANTING THT IMAG I NATION ln TheLion, TheWitch and the Wardrobe,the first book writerJ.R.R.Tolkien; the two men began Lewiswrote aboutNarnia, four British children aresent a writing-and-discussiongroup called to live with an old professorduring the bombings the Inklings. Tolkien and other Inklings of London in World War II. Each of the children is a played alargerole in helpingLewis came little like all of us: Lucy has a childlike trust and the face-to-facewith the claimsof the Gospel wonder of innocence,Edmund carriesthe resentment ofJesusChrist. As a Christianapologist, and one-upmanshipof ordinary selfishness,Susan Lewis wrote some of the 20th century's representsthe skepticismof the almost-grown,and Peter most important books on faith (The showsthe impartialityand valor to which eachof us Screw tape Letter s, MereChristianity, longs to be called. SutyrisedbyJoy, The Great Divorce) as c.s. tEwls ATHts DESK StorySummary THE LEWISFAMILY WARDROBE well as the sevenNarnia Chronicles. While exploringthe house,Lucy the youngest,climbs through a magicwardrobe Why Did Lewis Write the Chronicles? into Narnia,a land of talking animalsand m;,thicalcreatures who areunder the Lewis himselfstated that the taleswere not allegoriesand thereforeshould not evil White Witch'sspell of endlesswinter. When Lucy returns,her brothersand be "decoded."He preferredto think of them as "supposals,"as he explainedin 'supposing sisterdont believeher tale.Edmund entersNarnia a few dayslater and meetsthe this letter to a young woman namedAnne: "I askedmyself, that White Witch, who feedshim TurkishDelight and promisesto makehim a prince therereally was a world like Narnia and supposingit had (like our world) gone of Narnia if he will bring his siblingsto her. -

Chronicles of Narnia Jump V.0.0.1

Chronicles of Narnia Jump v.0.0.1 Backgrounds: You show up with the same gender as your previous jump, or you can pay [50] to choose your age and gender. Drop-In [0] You've managed to stumble into a world of magic and wonder. Perhaps destiny has something special in store for you, or Narnian [0] You're from Narnia, born and raised. Depending on the era, the land might be primarily inhabited by humans, talking animals, or some cosmopolitan mixture of the two. Outlander [0] You might be from Calormen, the Underworld, the Lands beyond the Sea, or even another universe entirely. In addition to your background, choose a species. Human [0] You're a Son of Adam or a Daughter of Eve, with all the associated entitlements and responsibilities that come along with that. Starting age is 1d8+9 for Drop Ins, 1d8+13 for other backgrounds. Talking Animal [0] You're dangerously furry. Note that the smallest animals are scaled up somewhat, and the largest are scaled down. A talking mouse might stand more than two feet tall, a talking elephant eight or nine. Dwarf [0] You're short and stocky. You have a beard. C'mon, you know what a Dwarf is. Demihuman [0] You might be a faun, satyr, centaur, minotaur, or some stranger mixture of human and animal parts. There might even be some plant parts thrown in there for good measure. Marsh-Wiggle [0] A race of grumpy, web-toed, swamp-dwelling frog people. You might be short and very fat or tall and very thin, but few Marsh-Wiggles are anywhere in between. -

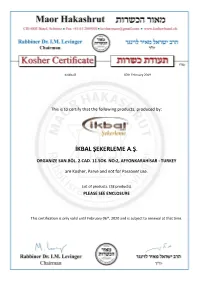

Ikbal Şekerleme A.Ş

Koikbal3 07th February 2019 This is to certify that the following products, produced by: İKBAL ŞEKERLEME A.Ş. ORGANİZE SAN.BÖL. 2.CAD. 11.SOK. NO:2, AFYONKARAHİSAR - TURKEY are Kosher, Parve and not for Passover use. List of products: (38 products) PLEASE SEE ENCLOSURE This certification is only valid until February 06th, 2020 and is subject to renewal at that time. ENCLOSURE LIST OF THE PRODUCTS of İKBAL ŞEKERLEME A.Ş. ORGANİZE SAN.BÖL. 2.CAD. 11.SOK. NO:2, AFYONKARAHİSAR - TURKEY INCLUDED IN THE KOSHER - CERTIFICATE OF 07/02/2019 1. TRADITIONAL DOUBLE ROASTED TURKISH DELIGHT WITH TURKISH COFFEE AND PISTACHIO (COVERED WITH ICING SUGAR) 2. TRADITIONAL DOUBLE ROASTED ASSORTED TURKISH DELIGHT (COVERED WITH COCONUT) (PISTACHIO-HAZELNUT-ALMOND) 3. TRADITIONAL DOUBLE ROASTED TURKISH DELIGHT WITH PISTACHIO (COVERED WITH CHOCOLATE) 4. TRADITIONAL DOUBLE ROASTED TURKISH DELIGHT WITH PISTACHIO (COVERED WITH ICING SUGAR) 5. TRADITIONAL DOUBLE ROASTED PASHA TURKISH DELIGHT WITH PISTACHIO 6. TRADITIONAL DOUBLE ROASTED PRINCESS TURKISH DELIGHT WITH HAZELNUT 7. TRADITIONAL DOUBLE ROASTED TURKISH DELIGHT WITH EXTRA RICH PISTACHIO 8. TRADITIONAL DOUBLE ROASTED TURKISH DELIGHT WITH PISTACHIO (COVERED WITH COCONUT) 9. TRADITIONAL TURKISH DELIGHT COVERED WITH ICING SUGAR 10. TRADITIONAL SMALL CUT ASSORTED FRUIT FLAVOURED TURKISH DELIGHT (COVERED WITH ICING SUGAR), (KIWI - LEMON - ORANGE - BANANA - STRAWBERRY) 11. TRADITIONAL SMALL CUT ASSORTED FRUIT FLAVOURED TURKISH DELIGHT (COVERED WITH COCONUT) 12. TURKISH DELIGHT WITH FRUIT FLAVOUR & MIX NUTS COVERED WITH ICING SUGAR 13. TRADITIONAL ROSE - LEMON - ORANGE FLAVORED TURKISH DELIGHT (COVERED WITH ICING SUGAR) 14. TRADITIONAL TURKISH DELIGHT WITH GUM MASTIC (COVERED WITH ICING SUGAR) 15. TRADITIONAL ROSE FLAVORED TURKISH DELIGHT (COVERED WITH ICING SUGAR) 16. -

Filozofická Fakulta Univerzity Palackého

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky A Comparative Analysis of Two Czech Translations of The Chronicles of Narnia with Focus on Domestication and Foreignization Diplomová práce Autor: Bc. Kateřina Gabrielová Studijní obor: Angličtina se zaměřením na tlumočení a překlad Vedoucí: Mgr. Ondřej Molnár Olomouc 2016 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně a uvedla úplný seznam citované a použité literatury. V Olomouci dne ............................ Podpis:............................ Motto: What doesn't kill you makes you stronger. Acknowledgement I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Mgr. Ondřej Molnár for his supportive and patient guidance, as well as to my family and friends for their endless support. Abstract This Master’s thesis aimed at comparing translating of proper names in two Czech translations of The Chronicles of Narnia from the point of view of domestication and foreignization. Domestication and foreignization are global translations strategies dealing with to what degree texts are adjusted to the target culture. One of the challenges related to domestication and foreignization is translation of proper names. In the research, proper names are analyzed via the two translation strategies. The translations used for the analysis were performed by the translators Renata Ferstová and Veronika Volhejnová respectively. Key words domestication, foreignization, naturalization, alienating, translation of proper names, The Chronicles of Narnia Anotace Tato diplomová práce se zabývá komparativní analýzou překladu vlastních jmen ve dvou českých překladech Letopisů Narnie z pohledu domestikace a exotizace. Domestikace a exotizace jsou definovány jako globální překladatelské strategie, které řeší do jaké míry je překlad přizpůsoben cílové kultuře. Jeden z fenoménů, který je zahrnut do problematiky domestikace a exotizace je překlad vlastních jmen.