The Internationalization of Food Television Show Formats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 Pitching Profiles for TV Producers Media Contacts

2013 Pitching Profiles for TV Producers Media Contacts A Cision Executive Briefing Report | January 2013 Cision Briefing Book: TV Producers Regional Cable Network | Time Warner Inc., NY 1 News, Mr. Matt Besterman, News, Executive Producer Shipping Address: 75 9Th Ave Frnt 6 DMA: New York, NY (1) New York, NY 10011-7033 MSA: New York--Northern NJ--Long Island, NY--NJ--PA MSA (1) United States of America Mailing Address: 75 9Th Ave Frnt 6 Phone: +1 (212) 691-3364 (p) New York, NY 10011-7033 Fax: +1 (212) 379-3577 (d) United States of America Email: [email protected] (p) Contact Preference: E-Mail Home Page: http://www.ny1.com Profile: Besterman serves as Executive Producer for NY 1 News. He is a good contact for PR professionals pitching the program. When asked if there is any type of story idea in particular he’s interested in receiving, Besterman replies, “We don’t really know what we might be interested in until we hear about it. But it has to relate to New Yorkers.” Besterman is interested in receiving company news and profiles, event listings, personality profiles and interviews, public appearance information, rumors and insider news, and trend stories. On deadlines, Besterman says that each program is formulated the day of its broadcast, but he prefers to books guests several days in advance. Besterman prefers to be contacted and pitched by email only. Besterman has been an executive producer at New York 1 News since November 2000. He previously worked as a producer at WRGB-TV in Albany, NY since March 1998. -

On the Ball! One of the Most Recognizable Stars on the U.S

TVhome The Daily Home June 7 - 13, 2015 On the Ball! One of the most recognizable stars on the U.S. Women’s World Cup roster, Hope Solo tends the goal as the U.S. 000208858R1 Women’s National Team takes on Sweden in the “2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup,” airing Friday at 7 p.m. on FOX. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., June 7, 2015 — Sat., June 13, 2015 DISH AT&T CABLE DIRECTV CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA SPORTS BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING 5 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 Championship Super Regionals: Drag Racing Site 7, Game 2 (Live) WCIQ 7 10 4 WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Monday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 8 p.m. ESPN2 Toyota NHRA Sum- 12 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 mernationals from Old Bridge Championship Super Regionals Township Race. -

Beat the Heat

To celebrate the opening of our newest location in Huntsville, Wright Hearing Center wants to extend our grand openImagineing sales zooming to all of our in offices! With onunmatched a single conversationdiscounts and incomparablein a service,noisy restaraunt let us show you why we are continually ranked the best of the best! Introducing the Zoom Revolution – amazing hearing technology designed to do what your own ears can’t. Open 5 Days a week Knowledgeable specialists Full Service Staff on duty daily The most advanced hearing Lifetime free adjustments andwww.annistonstar.com/tv cleanings technologyWANTED onBeat the market the 37 People To Try TVstar New TechnologyHeat September 26 - October 2, 2014 DVOTEDO #1YOUTHANK YOUH FORAVE LETTING US 2ND YEAR IN A ROW SERVE YOU FOR 15 YEARS! HEARINGLeft to Right: A IDS? We will take them inHEATING on trade & AIR for• Toddsome Wright, that NBC will-HISCONDITIONING zoom through• Dr. Valerie background Miller, Au. D.,CCC- Anoise. Celebrating• Tristan 15 yearsArgo, in Business.Consultant Established 1999 2014 1st Place Owner:• Katrina Wayne Mizzell McSpadden,DeKalb ABCFor -County HISall of your central • Josh Wright, NBC-HISheating and air [email protected] • Julie Humphrey,2013 ABC 1st-HISconditioning Place needs READERS’ Etowah & Calhoun CHOICE!256-835-0509• Matt Wright, • OXFORD ABCCounties-HIS ALABAMA FREE• Mary 3 year Ann warranty. Gieger, ABC FREE-HIS 3 years of batteries with hearing instrument purchase. GADSDEN: ALBERTVILLE: 6273 Hwy 431 Albertville, AL 35950 (256) 849-2611 110 Riley Street FORT PAYNE: 1949 Gault Ave. N Fort Payne, AL 35967 (256) 273-4525 OXFORD: 1990 US Hwy 78 E - Oxford, AL 36201 - (256) 330-0422 Gadsden, AL 35901 PELL CITY: Dr. -

France's Banijay Group Buys Endemol Shine to Create European Production Giant

Publication date: 28 Oct 2019 Author: Tim Westcott Director, Research and Analysis, Programming France's Banijay Group buys Endemol Shine to create European production giant Brought to you by Informa Tech France's Banijay Group buys Endemol Shine to 1 create European production giant France-based production company Banijay Group has reached agreement to acquire Endemol Shine Group from Walt Disney Company and US hedge fund Apollo Global Management. The price for the deal was not disclosed but is widely reported to be $2.2 billion. A statement from the group said the deal will be financed through a capital increase of Banijay Group and debt. On closure, subject to regulatory clearances and employee consultations. Post-closing, the combined group will be majority owned (67.1%) by LDH, the holding company controlled by Stephane Courbit's LOV Group, and Vivendi (32.9%), which invested in Banijay in 2014. The merged group said it will own almost 200 production companies in 23 territories and the rights for close to 100,000 hours of content, adding that total pro-forma revenue of the combined group is expected to be €3 billion ($3.3 billion) this year. Endemol Shine Group is jointly owned by Disney, which acquired its 50% stake as part of its acquisition of 21st Century Fox last year, and funds managed by affiliates of Apollo Global Management. Endemol Shine has 120 production labels and owns 66,000 hours of scripted and non- scripted programming and over 4,300 registered formats. Our analysis Endemol Shine Group has been up for sale since last year, and Banijay Group appears to be have been the only potential buyer to have made an offer, despite reported interest from All3Media, RTL Group-owned Fremantle and others. -

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

Cleveland, Tn 37311

SPORTS: LOCAL NEWS: Fifth-ranked Raiders Region taking head into district as notice of area top seed: Page 9 growth: Page 13 162nd yEAR • No. 306 16 PAGES • 50¢ CLEVELAND, TN 37311 THE CITY WITH SPIRIT TUESDAY, APRIL 25, 2017 Teachers’ pay concerns voiced Tennessee Crye urges fellow legislators commissioners to give nod to beware of future gas tax hike By BRIAN GRAVES [email protected] One of the Bradley County commissioners took Local projects advantage of an empty agenda Monday night to express his concerns about the pay for county teachers. total $220M Commissioner Thomas Crye said Director of Schools Dr. Linda Cash had advised him she has By BRIAN GRAVES [email protected] been told the county schools will take a $700,000 hit in state BEP funds. The Tennessee House of “All of us should think Representatives voted Monday “I’m not making a our teachers deserve a night to concur with the state howell demand. I’m not minimum pay raise at Senate and give the final making a request. I’m least in the amount of approval to Gov. Bill Haslam’s making an observa- what the Bradley County transportation infrastructure tion and laying it out employees receive,” Crye act. on the table. We have said. The final vote was 67-21. a storm over the hori- County employees The bill prioritizes 962 proj- zon that we need to have gotten 2 percent ects across all of Tennessee’s be aware of.” raises for the last few Banner photo, BRIAN GRAVES 95 counties, addressing a — Commissioner years. -

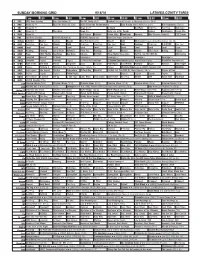

Sunday Morning Grid 9/18/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/18/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) 2016 Evian Golf Championship Auto Racing Global RallyCross Series. Rio Paralympics (Taped) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch BestPan! Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Skin Care 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Vista L.A. at the Parade Explore Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Why Pressure Cooker? CIZE Dance 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Good Day Game Day (N) Å 13 MyNet Arthritis? Matter Secrets Beauty Best Pan Ever! (TVG) Bissell AAA MLS Soccer Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Church Faith Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Paid Prog. AAA Cooking! Paid Prog. R.COPPER Paid Prog. 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Three Nights Three Days Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr. ADD-Loving 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Pagado Secretos Pagado La Rosa de Guadalupe El Coyote Emplumado (1983) María Elena Velasco. -

Fruitteelt 47A.Indd

fruitteelt 24 november 2012, jaargang 102, nr 47 weekblad van de nederlandse fruittelers organisatie Thema Social media Interpoma weer bol van innovaties | Ethyleen, een boef voor fruitbomen in bewaring TE KOOP GEVRAAGD: Rentmeesters- Makelaars- & Taxatiekantoor - SCHILAPPELEN VAN GELLICUM VASTGOED b.v. Blokzijlerdwarsweg 12, Marknesse - INDUSTRIE- Tel 0527-203917, Fax 0527-203944 Mob. 06-53294479 APPELEN Wat is uw Fruitbedrijf waard? Overname Toekomstige woningbouw / industrie of natuur Laat Schulp uw Maatschappen fruit flessen! Wetvoorkeursrecht Gemeenten Ons kantoor is gespecialiseerd in de Nederlandse fruitsector op het gebied van: NIEUWE PACHTRECHT (KORTE PACHT) TE KOOP GEVRAAGD BOOMGAARDEN TAXATIES FRUITTEELTBEDRIJF IN ONTEIGENING EN SCHADEREGELINGEN MIDDEN NEDERLAND (discretie verzekerd) AAN- EN VERKOOP BEGELEIDING www.schulp.nl GEWASSCHADE Schulp Vruchtensappen, Breukelen Gaarne schriftelijke reacties Telefoon: 0346-25 96 30 onder nummer 17633 Neem vrijblijvend contact met ons op. Van Gellicum Vastgoed b.v. Te Koop: Zeer goedefruit-oostrom.indd 1boompalen:06-08-2012 09:26:24 Roodseweg 11 2,5 mtr doorsnee 6 cm, 4156 AP Rumpt (Geldermalsen) 2.75 mtr doorsnee 6 cm 0345 - 651635 en 3 mtr doorsnee 10 cm. 06 - 51260930 Inlichtingen: Tel 06-13013524 www.vangellicumvastgoed.nl fruit-veldhuis 121112.indd 1 12-11-12 11:44 Inhoud Coverfoto 6 Mobiel internet en fruitteelt- apps, doen! 9 Digitale evolutie gaat Interpoma dat eind vorige week fruitteelt niet voorbij in Bolzano (Italië) werd gehou- den, is de grootste vakbeurs voor 6 de fruitsector -

Word Search Bilquis (Yetide) Badaki Unite Call (972) 937-3310 © Zap2it

Looking for a way to keep up with local news, school happenings, sports events and more? 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad April 28 - May 4, 2017 We’ve got you covered! waxahachietx.com The quest for the A L Y R E L J Q A R A B V A H 2 x 3" ad S A Q I S M A U M C S H A N E Your Key P U D Y H C E A W F E L B E W To Buying Triple Crown begins T R U K A R H A F I M K O N D M A P V E W A R W G E S D B A and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad B R O W N I N G E A K A Y U H I D O L Z T W H W I T T G K S L P U G U A B E S M B Q U I Q Q E S N Q S E E D A W E A V I U B H X I W L T E N Q O R E P I K A U K T I K M B E L D Y E S A C D T V E T A W R S I S E A B E I A D V T D E R G D U M P E H A V K E S H A D O W A N T W A M C A I L A V Y H L X Y “American Gods” on Starz (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Shadow (Moon) (Ricky) Whittle (Neil) Gaiman Place your classified Solution on page 13 (Mr.) Wednesday (Ian) McShane Bodyguard ad in the Waxahachie Daily 2 x 3" ad Laura (Moon) (Emily) Browning Believe Light, Midlothian1 xMirror 4" ad and Mad (Sweeney) (Pablo) Schreiber Power Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search Bilquis (Yetide) Badaki Unite Call (972) 937-3310 © Zap2it The 143rd Kentucky Derby airs Saturday on NBC. -

Sponsorship Opportunities Overview of the Event

Sponsorship opportunities Overview of the event • Friday 2 October 2015, 6.30pm – 1am at Villa Park • Michelin starred Chef, Glynn Purnell, presents a unique, live culinary event in front of an audience of 400 guests at Aston Villa Football Club, hosted by Gregg Wallace, with special guests on stage • Glynn’s specially designed four course menu will be cooked and served to guests by the talented team at Aston Villa’s award-winning Restaurant VMF, under the expert supervision of Executive Chef, Pete Reed • All proceeds from the event will go towards Cure Leukaemia, the pioneering, Birmingham-based charity of which Glynn is a Trustee Birmingham’s exciting new culinary event! Watch our highlights video from 2014 here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AlKEP3w6mWs#t=10 Our 2014 sponsors included: A message from our very own @yummiebrummie “I’m excited to let you know that this October will see the return of my Friday Night Kitchen, a live culinary experience complete with fantastic entertainment in front of an audience of 400 guests at Aston Villa Football Club. Following the success of last year’s event, I’ll be inviting a few of my friends from TV to join me on stage, hosted by Gregg Wallace, to share plenty of stories and laughs as I prepare four specially designed courses for guests to enjoy. With fantastic food, drink and entertainment until the early hours, it’ll be a Friday night to remember. Thank you for taking the time to consider supporting this event. Sponsorship means that every penny raised will go directly to Cure Leukaemia, led by Professor Charlie Craddock, to support life-saving clinical drugs trials in the West Midlands.” Celebrity involvement Glynn Purnell Glynn has been a driving force in Birmingham’s culinary scene ever since securing the city’s first Michelin star for Jessica’s in 2005. -

Lion Television Scotland's Contribution to the Consultation on the BBC's Plans to Launch a New Television Channel for Scotland in the Autumn of 2018

Please accept this email and the attached data protection release form as Lion Television Scotland's contribution to the consultation on the BBC's plans to launch a new television channel for Scotland in the autumn of 2018. Lion Television Scotland has produced hundreds of hours of content for all Broadcasters from our Glasgow base since the company launched in 1999. We produce BBC One flagship Daytime series Homes under the Hammer, employing a production team of more than 20 in our Glasgow office. In addition to that we are making the seventh series of the award winning Officially Amazing for CBBC and an arts documentary about the theft of two Van Gogh paintings for BBC Four. Other recent commissions include Daytime show Hoarder SOS for Channel 4, World of Weird also for Channel 4 and Time Commanders with Gregg Wallace for BBC Four. Any investment in Scotland's television industry is welcome and 30 million pounds for a new channel - 18 million in new money and 12 million from BBC Scotland from programmes currently on BBC Two - is a positive first step. And we note and appreciate this is the BBC's single largest investment in Scotland for twenty years - there is lots to be excited about. But to give the BBC and independent producers a fighting chance to deliver a quality service that audiences will want to watch that investment will have to increase over time. 100 million pounds is a figure that has been regularly quoted to launch a new service. The BBC said one of its aims in launching the new service was to improve the ratio between Licence Fee raised in Scotland and BBC spend in Scotland across all services. -

Ale Estuda Criar Cpi Para Apurar Desvios No Fecoep Crise Na

MACEIÓ, 16 A 22/03/2019 ANO LXXXV - Nº 4544 R$ 4,00 82.98151-4496 ALE ESTUDA CRIAR CPI PARA APURAR DESVIOS NO FECOEP Iniciativa é do deputado estadual Bruno Toledo (Pros), que já integrou o Conselho de Políticas de Inclusão Social do fundo e denuncia desvios na aplicação dos recursos. O governo Renan Filho está usando dinheiro do Fecoep para a construção de hospitais e outras fina- lidades, mas o parlamentar lembra que o fundo foi criado para promover ações que combatam efetivamente a pobreza no Estado. A3 AILTON CRUZ CRISE NA EDUCAÇÃO AFETA MERENDA, TRANSPORTE ESCOLAR E ENSINO INTEGRAL Cerca de 200 mil estudantes da rede estadual de ensino em todo o Estado podem ficar sem transporte se o governo não pagar R$ 12 milhões que deve aos donos de 800 ônibus escolares. Em estabelecimentos do Cepa, alunos reclamam da baixa qualidade da merenda. Nas escolas de ensino em tempo integral, faltam professores e pessoal de apoio, e cresce a evasão de alunos. Sindicato critica a política educacional do governo. C1 a C3 Grupo espanhol compra aeroporto de Maceió A14 FREEPIK DIVULGAÇÃO GAZETAWEB Mais de 53% dos MEIs de Alagoas estão inadimplentes A13 ‘AMOR TÓXICO’ CAZUADINHA EM ALTA DIA MUNDIAL DA ÁGUA ‘É impossível conviver Confira relatos de quem já foi víti- Destaque no carnaval da Bahia, Não há muito o que comemorar com cultura do ódio’, diz ma de relação abusiva e veja como banda alagoana começa a ganhar em Alagoas: poluição castiga cada identificar e escapar do problema. notoriedade nacional. B1 e B2 vez mais o mar, lagoas e rios.