Capacity Utilization: Concept, Measurement, and Recent Estimates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of Paul A. Samuelson's Economics

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. A Study of Paul A. Samuelson's Econol11ics: Making Economics Accessible to Students A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics at Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand. Leanne Marie Smith July 2000 Abstract Paul A. Samuelson is the founder of the modem introductory economics textbook. His textbook Economics has become a classic, and the yardstick of introductory economics textbooks. What is said to distinguish economics from the other social sciences is the development of a textbook tradition. The textbook presents the fundamental paradigms of the discipline, these gradually evolve over time as puzzles emerge, and solutions are found or suggested. The textbook is central to the dissemination of the principles of a discipline. Economics has, and does contribute to the education of students, and advances economic literacy and understanding in society. It provided a common economic language for students. Systematic analysis and research into introductory textbooks is relatively recent. The contribution that textbooks play in portraying a discipline and its evolution has been undervalued and under-researched. Specifically, applying bibliographical and textual analysis to textbook writing in economics, examining a single introductory economics textbook and its successive editions through time is new. When it is considered that an economics textbook is more than a disseminator of information, but a physical object with specific content, presented in a particular way, it changes the way a researcher looks at that textbook. -

Capacity Utilization, Inflation and Monetary Policy

Capacity Utilization, Inflation and Monetary Policy: Classicals, post-Keynesians and the New Keynesian Consensus Peter Kriesler and Marc Lavoie1 Abstract The paper looks at the adjustment process towards long run equilibrium within Marxian models, defined in terms of normal rates of capacity utilization. The model is reduced to three essential equations: an IS equation, a Phillips curve equation and an central bank reaction function. It is shown that long run convergence depends on the specific inflation (Phillips curve) equation, and on the central bank setting a zero inflationary target. When these conditions are relaxed, the results are shown to accord more closely with post-Keynesian results. The Marxian model is then contrasted with New Consensus models, which only varies in its inflation/Phillips curve equation. Post-Keynesian criticisms of both the IS and the Phillips curve equation are considered, and suggestions for a post-Keynesian alternative are made. Keywords: monetary policy, central bank, inflation, capacity utilization, post-Keynesian, New- Keynesian JEL classification: E12, E40, E52, E58 In an extremely interesting paper, Duménil and Lévy (Duménil and Lévy 1999) explore the adjustment mechanism of an economy towards a long run equilibrium with capacity utilization at normal levels − a fully adjusted position as the Sraffians would call it, or a classical long-term equilibrium as Duménil and Lévy have it. Short run equilibrium within their model is of the Keynes/Kalecki type, with variability in levels of capacity utilization. One distinctive feature of their model is that it is not the forces of competition which push the economy to a fully adjusted position, but rather aspects of the macro economy coupled with the behaviour of the central bank. -

Rolling the DICE: William Nordhaus's Dubious Case for a Carbon

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Rolling the DICE William Nordhaus’s Dubious Case for a Carbon Tax F ROBERT P. M URPHY he 2007 Nobel Peace Prize awarded to Al Gore and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) underscores the public’s growing aware- T ness of and concern about anthropogenic (man-made) global warming. Many climatologists and other relevant scientists claim that emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) from human activity will lead to increases in the earth’s temperature, which in turn will spell potentially catastrophic hardship for future generations. -

Employment and Capacity Utilization Over the Business Cycle

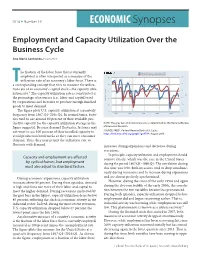

2016 n Number 19 ECONOMIC Synopses Employment and Capacity Utilization Over the Business Cycle Ana Maria Santacreu, Economist he fraction of the labor force that is currently Capacity Utilization: Total Industry (left) 100-Civilian Unemployment Rate (right) 98 employed is often interpreted as a measure of the 90 utilization rate of an economy’s labor force. There is 96 T 85 a corresponding concept that tries to measure the utiliza- tion rate of an economy’s capital stock—the capacity utili- 94 80 zation rate.1 The capacity utilization rate is constructed as 100-% 92 the percentage of resources (i.e., labor and capital) used 75 Percent of Capacity by corporations and factories to produce enough finished 90 goods to meet demand. 70 88 The figure plots U.S. capacity utilization at a quarterly 65 frequency from 1967:Q1–2016:Q1. In normal times, facto- 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 ries tend to use around 80 percent of their available pro- fred.stlouisfed.org myf.red/g/6ZXZ ductive capacity (as the capacity utilization average in the NOTE: The gray bars indicate recessions as determined by the National Bureau figure suggests). Because demand fluctuates, factories may of Economic Research. SOURCE: FRED®, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; not want to use 100 percent of their installed capacity to https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=6TA4; August 2016. avoid production bottlenecks so they can meet consumer demand. Thus, they may permit the utilization rate to fluctuate with demand. increases during expansions and decreases during recessions. In principle, capacity utilization and employment should Capacity and employment are affected comove closely, which was the case in the United States by cyclical factors, but employment during the period 1967:Q1–1990:Q1. -

Imbalance Game 2.0: a Tale of Two Productivities

NEW THINKING Imbalance Game 2.0: A Tale of Two Productivities Michael Craig, CFA Vice President & Director Haining Zha, CFA Vice President September 2017 Almost nine years after the financial crisis, the global economy remains mired in low growth. Low productivity growth is certainly a key contributing factor, but our research shows that current productivity measures don’t tell the whole story. In this article, we propose a fundamental change to how people should examine productivity: we believe the supply and demand sides should be viewed separately to obtain more robust insights. Taking this approach allows us to differentiate supply-side progress from demand-side malaise and shows that the economy may be more promising than commonly thought. In addition, it highlights large supply-side divergences within and across different sectors of the economy, which are not reflected in the aggregate productivity measure – potentially leading to a distorted economic picture. Viewing productivity through this new lens, we believe that: • Nominal economic growth will remain low • Inflation will remain subdued • Interest rates will stay lower for longer • Technology-driven progress and persistent supply-side divergence will create investment risks and opportunities in equity markets In the investment world, economic growth is a big deal. We believe investment returns across asset classes can ultimately be traced back to one source: economic growth. Occasionally, asset prices can deviate from fundamentals, but over the long term, the relationship between returns and growth is very strong. That’s why it is critical to have a better understanding of the low growth phenomenon and key contributing factors, such as productivity. -

Paul Samuelson and Global Public Goods

Paul Samuelson and Global Public Goods William D. Nordhaus Yale University1 May 5, 2005 A commemorative essay for Paul Samuelson ________________________________________________________ It is both easy and hard to write an essay commemorating Paul Samuelson’s contributions to economics. Easy, because he has created so much of modern economics that you could write on virtually anything – stabilization policy, economic growth, international trade, welfare economics, or just about any topic that caught your fancy. Hard, because, like Buridan’s ass, you could easily procrastinate forever in deciding which of the many treasures of his ideas to draw from. In the end, I chose to draw from Paul’s writings on public goods. In two and one-half pages, he reshaped the way economists and political philosophers think about the distinction between private goods and public goods.2 Once those concepts are learned, we can never again forget why the allocational questions for bread are fundamentally different from those of lighthouses. I will focus on an important example of this topic, and one that poses particularly thorny practical 1 The author is Sterling Professor of Economics at Yale University. 2 Paul Samuelson, “The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 36, No. 4, Nov. 1954, pp. 387-389. - 1 - issues, which is the case of global public goods. A brief intellectual history of the concepts is appended. What great blessings or scourges have befallen humanity? Consider issues as disparate as greenhouse warming and ozone depletion, the Internet and William Shakespeare, terrorism and money laundering, the discovery of antibiotics and nuclear proliferation. -

Notes on the Accumulation and Utilization of Capital: Some Theoretical Issues

Working Paper No. 952 Notes on the Accumulation and Utilization of Capital: Some Theoretical Issues by Michalis Nikiforos* Levy Economics Institute of Bard College April 2020 * For useful comments, the author would like to thank participants at the 45th annual Eastern Economic Association conference in New York and those at the 23rd Forum for Microeconomics and Macroeconomics conference in Berlin. The usual disclaimer applies The Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Collection presents research in progress by Levy Institute scholars and conference participants. The purpose of the series is to disseminate ideas to and elicit comments from academics and professionals. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, founded in 1986, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, independently funded research organization devoted to public service. Through scholarship and economic research it generates viable, effective public policy responses to important economic problems that profoundly affect the quality of life in the United States and abroad. Levy Economics Institute P.O. Box 5000 Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504-5000 http://www.levyinstitute.org Copyright © Levy Economics Institute 2020 All rights reserved ISSN 1547-366X ABSTRACT This paper discusses some issues related to the triangle between capital accumulation, distribution, and capacity utilization. First, it explains why utilization is a crucial variable for the various theories of growth and distribution—more precisely, with regards to their ability to combine an autonomous role for demand (along Keynesian lines) and an institutionally determined distribution (along classical lines). Second, it responds to some recent criticism by Girardi and Pariboni (2019). I explain that their interpretation of the model in Nikiforos (2013) is misguided, and that the results of the model can be extended to the case of a monopolist. -

The Great Depression As a Historical Problem

Upjohn Institute Press The Great Depression as a Historical Problem Michael A. Bernstein University of California, San Diego Chapter 3 (pp. 63-94) in: The Economics of the Great Depression Mark Wheeler, ed. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 1998 DOI: 10.17848/9780585322049.ch3 Copyright ©1998. W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. All rights reserved. 3 The Great Depression as a Historical Problem Michael A. Bernstein University of California, San Diego It is now over a half-century since the Great Depression of the 1930s, the most severe and protracted economic crisis in American his tory. To this day, there exists no general agreement about its causes, although there tends to be a consensus about its consequences. Those who at the time argued that the Depression was symptomatic of a pro found weakness in the mechanisms of capitalism were only briefly heard. After World War II, their views appeared hysterical and exag gerated, as the industrialized nations (the United States most prominent among them) sustained dramatic rates of growth and as the economics profession became increasingly preoccupied with the development of Keynesian theory and the management of the mixed economy. As a consequence, the economic slump of the inter-war period came to be viewed as a policy problem rather than as an outgrowth of fundamental tendencies in capitalist development. Within that new context, a debate persisted for a few years, but it too eventually subsided. The presump tion was that the Great Depression could never be repeated owing to the increasing sophistication of economic analysis and policy formula tion. -

The Role of Models and Probabilities in the Monetary Policy Process

1017-01 BPEA/Sims 12/30/02 14:48 Page 1 CHRISTOPHER A. SIMS Princeton University The Role of Models and Probabilities in the Monetary Policy Process This is a paper on the way data relate to decisionmaking in central banks. One component of the paper is based on a series of interviews with staff members and a few policy committee members of four central banks: the Swedish Riksbank, the European Central Bank (ECB), the Bank of England, and the U.S. Federal Reserve. These interviews focused on the policy process and sought to determine how forecasts were made, how uncertainty was characterized and handled, and what role formal economic models played in the process at each central bank. In each of the four central banks, “subjective” forecasting, based on data analysis by sectoral “experts,” plays an important role. At the Federal Reserve, a seventeen-year record of model-based forecasts can be com- pared with a longer record of subjective forecasts, and a second compo- nent of this paper is an analysis of these records. Two of the central banks—the Riksbank and the Bank of England— have explicit inflation-targeting policies that require them to set quantita- tive targets for inflation and to publish, several times a year, their forecasts of inflation. A third component of the paper discusses the effects of such a policy regime on the policy process and on the role of models within it. The large models in use in central banks today grew out of a first generation of large models that were thought to be founded on the statisti- cal theory of simultaneous-equations models. -

Political Business Cycles 40 Years After Nordhaus Eric Dubois

Political Business Cycles 40 Years after Nordhaus Eric Dubois To cite this version: Eric Dubois. Political Business Cycles 40 Years after Nordhaus. Public Choice, Springer Verlag, 2016, 166 (1-2), pp.235-259. 10.1007/s11127-016-0313-z. hal-01291401 HAL Id: hal-01291401 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01291401 Submitted on 21 Mar 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Political Business Cycles 40 Years after Nordhaus Eric Dubois1 Abstract: The aim of this article is to survey the huge literature that has emerged in the last four decades following Nordhaus’s (1975) publication on political business cycles (PBCs). I first propose some developments in history of thought to examine the context in which this ground-breaking contribution saw the light of the day. I also present a simplified version of Nordhaus’s model to highlight his key results. I detail some early critiques of this model and the fields of investigations to which they gave birth. I then focus on the institutional context and examine its influence on political business cycles, the actual research agenda. Finally, I derive some paths for future research. -

Political Business Cycle and Economic Instability - Literature Review

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Tiganas, Claudiu-Gabriel; Peptine, Claudiu Article Political Business Cycle and Economic Instability - Literature Review CES Working Papers Provided in Cooperation with: Centre for European Studies, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University Suggested Citation: Tiganas, Claudiu-Gabriel; Peptine, Claudiu (2012) : Political Business Cycle and Economic Instability - Literature Review, CES Working Papers, ISSN 2067-7693, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iasi, Centre for European Studies, Iasi, Vol. 4, Iss. 4, pp. 853-865 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/198221 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend -

1017-04 BPEA/Nordhaus 12/30/02 15:01 Page 211

1017-04 BPEA/Nordhaus 12/30/02 15:01 Page 211 WILLIAM D. NORDHAUS Yale University Productivity Growth and the New Economy What, another paper on the new economy? When financial markets are raking through the debris of $8 trillion in lost equity value, and “.com” is a reviled four-symbol word, a paper on the impact of the new economy on productivity would seem as welcome as an analysis of the role of whales in the lighting revolution. In fact, the new economy (or, more precisely, information technolo- gies) continues to raise important puzzles about productivity growth. Variations in productivity growth have proved to be one of the most durable puzzles in macroeconomics. After a period of rapid growth fol- lowing World War II, productivity stagnated in the early 1970s. There was no shortage of explanations offered, including rising energy prices, high and unpredictable inflation, rising tax rates, growing government, burdensome environmental and health regulation, declining research and development, deteriorating labor skills, depleted possibilities for inven- tion, and societal laziness.1 Yet these explanations seemed increasingly inadequate as inflation fell, tax rates were cut, regulatory burdens stabi- lized, government’s share of output fell, research and development and patents granted grew sharply, real energy prices fell back to pre-1973 lev- els, and a burst of invention in the new economy and other sectors fueled an investment boom in the 1990s. The productivity slowdown puzzle of the 1980s evolved into the Solow paradox of the early 1990s: computers were everywhere except in the The author is grateful for comments from Ray Fair, Robert Yuskavage, and members of the Brookings Panel.