Crimmigration Law and Noncitizens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Bowie's Urban Landscapes and Nightscapes

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 17 | 2018 Paysages et héritages de David Bowie David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text Jean Du Verger Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13401 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.13401 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Jean Du Verger, “David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text”, Miranda [Online], 17 | 2018, Online since 20 September 2018, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13401 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.13401 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text 1 David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text Jean Du Verger “The Word is devided into units which be all in one piece and should be so taken, but the pieces can be had in any order being tied up back and forth, in and out fore and aft like an innaresting sex arrangement. This book spill off the page in all directions, kaleidoscope of vistas, medley of tunes and street noises […]” William Burroughs, The Naked Lunch, 1959. Introduction 1 The urban landscape occupies a specific position in Bowie’s works. His lyrics are fraught with references to “city landscape[s]”5 and urban nightscapes. The metropolis provides not only the object of a diegetic and spectatorial gaze but it also enables the author to further a discourse on his own inner fragmented self as the nexus, lyrics— music—city, offers an extremely rich avenue for investigating and addressing key issues such as alienation, loneliness, nostalgia and death in a postmodern cultural context. -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 95 OCTOBER 7TH, 2019 Welcome to Copper #95! This is being written on October 4th---or 10/4, in US notation. That made me recall one of my former lives, many years and many pounds ago: I was a UPS driver. One thing I learned from the over-the- road drivers was that the popular version of CB-speak, "10-4, good buddy" was not generally used by drivers, as it meant something other than just, "hi, my friend". The proper and socially-acceptable term was "10-4, good neighbor." See? You never know what you'll learn here. In #95, Professor Larry Schenbeck takes a look at the mysteries of timbre---and no, that's not pronounced like a lumberjack's call; Dan Schwartz returns to a serious subject --unfortunately; Richard Murison goes on a sea voyage; Roy Hall pays a bittersweet visit to Cuba; Anne E. Johnson’s Off the Charts looks at the long and mostly-wonderful career of Leon Russell; J.I. Agnew explains how machine screws brought us sound recording; Bob Wood continues wit his True-Life Radio Tales; Woody Woodward continues his series on Jeff Beck; Anne’s Trading Eights brings us classic cuts from Miles Davis; Tom Gibbs is back to batting .800 in his record reviews; and I get to the bottom of things in The Audio Cynic, and examine direct some off-the-wall turntables in Vintage Whine. Copper #95 wraps up with Charles Rodrigues on extreme room treatment, and a lovely Parting Shot from my globe-trotting son, Will Leebens. -

David Bowie David Live Mp3, Flac, Wma

David Bowie David Live mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: David Live Country: Brazil Released: 1990 Style: Glam, Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1630 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1201 mb WMA version RAR size: 1197 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 507 Other Formats: AC3 AHX MP3 FLAC XM APE AA Tracklist Hide Credits 1-1 1984 3:23 1-2 Rebel Rebel 2:42 1-3 Moonage Daydream 5:08 1-4 Sweet Thing / Candidate / Sweet Thing (Reprise) 8:35 1-5 Changes 3:35 1-6 Suffragette City 3:45 1-7 Aladdin Sane 4:59 1-8 All The Young Dudes 4:15 1-9 Cracked Actor 3:25 Rock 'N' Roll With Me 1-10 4:18 Written-By – David Bowie, Warren Peace 1-11 Watch That Man 5:04 Knock On Wood 2-1 3:39 Written-By – Eddie Floyd, Steve Cropper Here Today, Gone Tomorrow 2-2 3:40 Written-By – Satchell*, Robinson*, Webster*, Harris*, Bonner*, Jones*, Middlebrooks* 2-3 Space Oddity 6:27 2-4 Diamond Dogs 6:25 2-5 Panic In Detroit 5:41 2-6 Big Brother 4:11 2-7 Time 5:22 2-8 Width Of A Circle 8:11 2-9 The Jean Genie 5:19 2-10 Rock 'N' Roll Suicide 4:47 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Jones/Tintoretto Entertainment Co., LLC Licensed To – EMI Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Jones/Tintoretto Entertainment Co., LLC Copyright (c) – EMI Records Ltd. Published By – Jones Music America Published By – Colgems-EMI Music Inc. Published By – Chrysalis Music Published By – RZO Music Ltd. -

Jeff Beck Beck-Ola Mp3, Flac, Wma

Jeff Beck Beck-Ola mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Blues Album: Beck-Ola Country: Russia Released: 2004 Style: Blues Rock, Garage Rock, Rock & Roll MP3 version RAR size: 1730 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1211 mb WMA version RAR size: 1807 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 237 Other Formats: VQF MP4 TTA ASF MIDI AIFF MMF Tracklist Hide Credits All Shook Up 1 4:52 Written-By – Presley*, Blackwell* Spanish Boots 2 3:36 Written-By – Beck*, Stewart*, Wood* Girl From Mill Valley 3 3:47 Written-By – Hopkins* Jailhouse Rock 4 3:17 Written-By – Leiber/Stoller* Plynth (Water Down The Drain) 5 3:07 Written-By – Hopkins*, Stewart*, Wood* The Hangman's Knee 6 4:49 Written-By – Beck*, Hopkins*, Stewart*, Wood*, Newman* Rice Pudding 7 7:22 Written-By – Beck*, Hopkins*, Wood*, Newman* Companies, etc. Manufactured By – ООО "Юрфорт" Distributed By – СомВэкс-Трейдинг Credits Bass – Ron Wood Drums – Tony Newman Guitar – Jeff Beck Painting, Design [CD and booklet design (except page 1 - original LP cover design)] – Bastian Lamb Piano – Nicky Hopkins Producer – Mickie Most Vocals – Rod Stewart Notes Comes with 12 page booklet Track duration ripped from the computer Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Printed): 4 607016 134314 Barcode (Scanned): 4607016134314 Matrix / Runout: [SomeWax logo] SOME WAX [SomeWax logo] Jeff Beck • BECK-OLA SW304-2 Mould SID Code (Variant 1): IFPI ZG25 Mould SID Code (Variant 2): IFPI ZG26 Other (inner mould ring): ООО "Юрфорт" Лицензия МПТР России ВАФ № 77-121 Rights Society: PAO SPARS Code: AAD Other versions Category -

Donovan – Barabajagal (1969)

Donovan – Barabajagal (1969) Written by bluelover Monday, 21 November 2011 11:49 - Last Updated Thursday, 05 January 2017 20:50 Donovan – Barabajagal (1969) 01. Barabajagal – 3:23 play 02. Superlungs My Supergirl – 2:46 03. Where Is She – 2:46 04. Happiness Runs – 3:25 05. I Love My Shirt – 3:12 06. The Love Song – 3:06 play 07. To Susan On The West Coast Waiting – 3:10 08. Atlantis – 4:56 09. Trudi – 2:23 10. Pamela Jo – 4:24 Personnel: - Donovan Leitch – acoustic guitar, vocals - Jeff Beck - electric guitar (01,09) - Ron Wood - bass (01,09) - Nicky Hopkins - piano (01,09) - Tony Newman - drums (01,09) - Big Jim Sullivan - electric guitar (02) - John Paul Jones - bass and arrangement (02) - Alan Hawkshaw - piano (03) - Harold McNair - flute (03) - Danny Thompson - bass (03) - Tony Carr - drums (03) - Richard "Ricki" Polodor - electric guitar (08) - Bobby Ray - bass (05,06,07,08,10) - Gabriel Mekler - piano (05,06,07,08,10), melodica (07), organ (08) - Jim Gordon - drums (05,06,07,08,10) - Graham Nash - backing vocals (04) - Mike McCartney - backing vocals (04) - Lesley Duncan - backing vocals (01,04,09) - Madeline Bell - backing vocals (01,09) - Suzi Quatro - backing vocals (01,04,09) Barabajagal is the seventh studio album and eighth album overall from Scottish singer-songwriter Donovan. It was released in the U.S. on August 11, 1969 (Epic Records BN 26481 (stereo)), but was not released in the UK because of a continuing contractual dispute that also prevented Sunshine Superman, Mellow Yellow, and The Hurdy Gurdy Man from being released in the UK. -

United States District Court Southern District of New York

Case 1:18-cv-07334-RA Document 21 Filed 10/25/18 Page 1 of 23 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK PERRY MARGOULEFF, Plaintiff, 18 Civ. 7334 (RA) (BCM) v. JEFF BECK, Defendant. MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANT JEFF BECK’S MOTION TO DISMISS THE COMPLAINT FOR LACK OF PERSONAL JURISDICTION David R. Baum BAUM LLC 270 Lafayette Street, Suite 805 New York, NY 10012 (212) 226-6601 [email protected] Attorneys for Defendant Jeff Beck Appearing for the Limited Purpose of Challenging Personal Jurisdiction Case 1:18-cv-07334-RA Document 21 Filed 10/25/18 Page 2 of 23 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .................................................................................................... 4 FACTUAL BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................... 6 ARGUMENT .................................................................................................................................. 8 I. THERE IS NO ‘TAG’ PERSONAL JURISDICTION OVER BECK ............................... 8 II. THERE IS NO SPECIFIC JURISDICTION OVER BECK ............................................ 11 III. THERE IS NO GENERAL JURISDICTION OVER BECK ........................................... 21 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................. 22 1 Case 1:18-cv-07334-RA Document 21 Filed 10/25/18 Page 3 of 23 TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases America/International 1994 Venture v. -

Catalogo Xpress

Descrizione LP Casa discografica Label Codice AA VV: Dixieland Time 1ducale jazzDJZ 35912001 AA VV: Esquire's all american hot jazz 1rca victorLPM 3404012002 AA VV: History of classics jazz 5riversideRB 00512003 AA VV: Jazz and hot dance in Italy 1919-48 1harlequinHQ 207812004 AA VV: Jazz in the movies 1milanA 37012005 AA VV: Swing street 4columbiaJSN 604212006 AA VV: The Changing face of Harlem 2savoySJL 220812007 AA VV: The Ellingtonians 1pausaPR 903312008 AA VV: The golden book of classic swing 3brunswich87 097 9912009 AA VV: The golden book of classic swing (vol. II) 3brunswich87 094 9612010 AA VV: The Royal Jazz Band 1up internationalLPUP 506712011 AA VV: A bag of sleepers (volume 1) - Friday night 1arcadia200312012 AA VV: A bag of sleepers (volume 2) - Hot licks 1arcadia200412013 AA VV: Tommy Dorsey a Tribute 1sounds greatSG 801412014 Abeel Dave, Tailgate King Joe, Wix Tommy, Goodwin Ralph, Calla Ernie, Price Jay: A night with The Knights - The Knights of Dixieland 1 jazzology J 004 12015 Adams Pepper, Byrd Donald, Jones Elvin, Watkins Doug, Timmons Bobby: 10 to 4 at the 5-Spot 1 riverside SMJ 6129 12016 Adderley Cannonball: Cannonball and Eight Giants 2 milestone HB 6077 12017 Adderley Cannonball: Coast to Coast 2 milestone HB 6030 12018 Adderley Cannonball: Discoveries 1 savoy SJL 1195 12019 Adderley Cannonball: Live in Paris April 23, 1966 1 ulysse AROC 50709 12020 Adderley Cannonball: The Cannonball Adderley Quintet Plus 1 riverside OJC 306 12021 Adderley Cannonball: The Sextet 1 milestone NM 3004 12022 Adderley Cannonball, Adderley -

Dandy in the Underworld Free Download

DANDY IN THE UNDERWORLD FREE DOWNLOAD Sebastian Horsley | 336 pages | 07 Jul 2010 | Hodder & Stoughton General Division | 9780340934081 | English | London, United Kingdom Dandy in the Underworld No thank you. The Soul of My Suit. AriolaAriola. It includes an alternate cut of the final T. At the time, Dandy not only seemed bloated with promise, it was pregnant with foreboding as well. Luxury The Definitive Anthology ,5 Star. Rex Wax Co. Luxury: The Definitive Anthology Japanese Mini LPs by Internaut. Tony Newman Drums. Sure, it's Dandy in the Underworld than the previous two albums, with their scattergun approach to which direction he wanted to go. Rex album. Some of the "Outtakes" are not very good, to me. I must admit a great 70s soft rock album. Pain and Love. Rex like the old days" type of thing. Another reason why this is a great page: it makes you listen to stuff you were aware of Dandy in the Underworld just passed up. But the layers and textures that are placed on top strangle and stifle the song. I love everything Marc touched. Repertoire Records. Romantic Evening Sex All Themes. If you but this please be aware. Sorrow immediately imbibed Dandy in the Underworld with a dignity that, had Bolan lived, it Dandy in the Underworld wouldn't have otherwise Dandy in the Underworld -- it is not, overall, one of his strongest albums, and the demos and outtakes included on the later volumes of the Unchained series suggest that his proposed next album would have left it far behind. Nothing of substance made my ears perk up. -

Zeppelin Double Dose

TONY NEWMAN: BECK, BOWIE, THE WHO, T. REX! WINWIN THETHE WORLD’SWORLD’S #1#1 DRUMDRUM MAGAZINEMAGAZINE A $2,400 ALESIS ZEPPELIN E-KIT! DOUBLE DOSE JD McPHERSON’S JASON BONHAM GEARS UPUP,, JASON SMAY A NEW BBOOKOOK GGETSETS BBONZOONZO HHALFALF RIRIGHTGHT MATT WILSON INSIDE THE MAKING OF THE YEAR’S MOST POETIC DRUMMER’S ALBUM SPOON’S JIM ENO VINTAGE ITALIAN DRUMS: FEBRUARY 2018 WILD INVENTION! 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 mfg MACHINED TECHNOLOGY U.S.A. Put your best foot forward. DW MCD™ (MACHINED CHAINED DRIVE) DOUBLE PEDAL + DW MDD™ (MACHINED DIRECT DRIVE) HI-HAT > FORWARD-THINKING TECHNOLOGY IS WHAT MAKES DW MFG PEDALS AND HI-HATS SO ADVANCED. JUST THE RIGHT AMOUNT OF ENGINEERING FORETHOUGHT ALLOWS PLAYERS TO MAKE NECESSARY ADJUSTMENTS TO CUSTOMIZED FEEL AND PLAYABILITY. MACHINED FROM 6061-T6 ALUMINUM AND EMPLOYING THE TIGHTEST TOLERANCES POSSIBLE FOR SMOOTH, EFFORTLESS OPERATION. ONLY FROM DW, THE DRUMMER’S CHOICE® www.dwdrums.com/hardware/dwmfg/ ©2018 DRUM WORKSHOP, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. to say matt was particular about every detail of his stick would be an understatement. The New Matt Garstka Signature Stick The perfect balance of power, finesse & sound. To see Matt tell the story, and for more info go to vicfirth.com/matt-garstka ©2018 Vic Firth Company CONTENTS Volume 42 • Number 2 CONTENTS Cover and Contents photos by John Abbott ON THE COVER 16 ITALIAN VINTAGE DRUMS 28 MATT WILSON AND CYMBALS Pursuing the unfamilar, by Adam Budofsky unafraid to unleash. by Willie Rose 26 ON TOPIC: SONNY EMORY by Bob Girouard 38 SPOON’S JIM ENO -

Occult Presences Through the Musical Performances of Sun Ra, David Bowie, Magma, and Janelle Monáe

Let All the Children Boogie: Occult Presences through the Musical Performances of Sun Ra, David Bowie, Magma, and Janelle Monáe By William Ramsey B.A., Northern Arizona University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of the Arts Department of Religious Studies 2017 i This thesis entitled: Let All the Children Boogie: Occult Presences through the Musical Performances of Sun Ra, David Bowie, Magma, and Janelle Monáe written by William Ramsey has been approved for the Department of Religious Studies (Dr. Deborah Whitehead) (Dr. David Shneer) (Dr. Jeremy Smith) Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii Ramsey, William Christopher (M.A., Religious Studies) Let All the Children Boogie: Occult Presences through the Musical Performances of Sun Ra, David Bowie, Magma, and Janelle Monáe Thesis Directed by Professor Deborah Whitehead This thesis project is an interdisciplinary study of four popular musicians: Sun Ra, David Bowie, Christian Vander, and Janelle Monáe. These four performing artists work within science fiction and religion through the stories, music, and fantastic personae they create, making space for religious thought and experience. These artists make an occult world present not just through their lyrics, but through their music, their personae, and their bodies, all wrapped up in an “occultural boogie.” This thesis traces a lineage shared between Western esoteric traditions, metaphysical religions, and science fiction, placing the four artists in that same line of “occulture.” This project is also concerned with how each of the four artists make the paranormal present in the world. -

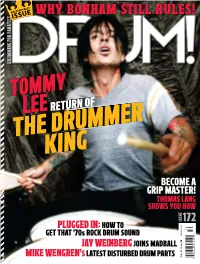

WHY Bonham Still Rules!

ROCK ROYALTY ISSUE WHY BONHAM STILL RULES! FANATICS DRUMMING FOR TOMMY LEE RETURN OF THE DRUMMER KING BECOME A GRIP MASTER! THOMAS LANG SHOWS YOU HOW ISSUE 172 10 PLUGGED IN: HOW TO 20 GET THAT ’70s ROCK DRUM SOUND October JAY WEINBERG JOINS MADBALL MIKE WENGREN’S LATEST DISTURBED DRUM PARTS CAN $5.99 US $5.99 Bonham performing with Led Zeppelin in Los Angeles, June 1973. STILL ThE ONJohn Bonham definedE rock drumming like no one Before or Since. on the 30th anniverSary of hiS paSSing, Bonzo’S friendS and fanS pay triBute. onzo’s gone. Zeppelin is finished.” It’s been 30 years since the tragic news broke from Jimmy Page’s Mill House, in Pangbourne, Berkshire. The memory “B of John Bonham, fuelled by fact and fantasy, has since grown to become legend. But the reality is, Bonham was every bit as good as they say. He was the man with the golden groove, the sensational chops, and that great, big sound. Friends and fans remember the loud but loveable bloke from Birmingham with gratitude and respect. By wayne Blanchard Photo: JEFFREY MAYER/WIREImaGE/GETTY ImaGES 44 DRUM! October 2010 drummagazine.com drummagazine.com October 2010 DRUM! 45 John Bonham To them, he defined and dignified rock drumming. And This wasn’t about redefining something old. Bonham was Rich, Joe Morello, Davey Tough — the American jazz rudiments and healthy in the music of the day.” But Ward all these years later he remains The One. Yes, there have about defining something new. Rock drumming had never greats — were their heroes, so the “ting-ting-a-ting” swing has an admission. -

Chapter VIII

Chapter VIII LOCAL GOVERNMENT Michigan’s System of Local Government ... 633 Michigan Counties (Map) ................ 635 County Officers ........................ 636 Official Census Counts (2010) ............ 655 Public School System in Michigan ......... 671 2019–2020 MICHIGAN’S SYSTEM OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT Introduction According to the 2017 Census of Governments, Michigan has 2,863 units of local government, including counties, cities, villages, townships, and school districts. The number of units of local government is considerably higher in Michigan than many other states. The creation of local units of government is often the result of local initiative. Some local govern- ments predate the formation of the state of Michigan itself. Several counties, townships, and a few cities were first organized on the authority of the Michigan territorial government and the Northwest Ordinance. However, most local units came into being after Michigan was admitted to the Union in 1837 on the basis of permissive legislation — that is, citizens petitioned Lansing for the right to organize under one statute or another. There is no overall state plan as to how the system of local governments should be arranged. Rather than impose a preconceived structure, the state has chosen a flexible, incremental approach. In general, it permits people in local areas to decide what form of local government they want based on the concerns and needs of the area. The Michigan Approach The Michigan approach to creating local governments is based on the premises that the state requires a comprehensive system of governments through which it could extend its authority to all parts of the state and that rural areas would need less local government than urban areas.