Educating for Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Anthropology Through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-Based Sentiment

Cultural Anthropology through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-based Sentiment Peter A. Gloor, Joao Marcos, Patrick M. de Boer, Hauke Fuehres, Wei Lo, Keiichi Nemoto [email protected] MIT Center for Collective Intelligence Abstract In this paper we study the differences in historical World View between Western and Eastern cultures, represented through the English, the Chinese, Japanese, and German Wikipedia. In particular, we analyze the historical networks of the World’s leaders since the beginning of written history, comparing them in the different Wikipedias and assessing cultural chauvinism. We also identify the most influential female leaders of all times in the English, German, Spanish, and Portuguese Wikipedia. As an additional lens into the soul of a culture we compare top terms, sentiment, emotionality, and complexity of the English, Portuguese, Spanish, and German Wikinews. 1 Introduction Over the last ten years the Web has become a mirror of the real world (Gloor et al. 2009). More recently, the Web has also begun to influence the real world: Societal events such as the Arab spring and the Chilean student unrest have drawn a large part of their impetus from the Internet and online social networks. In the meantime, Wikipedia has become one of the top ten Web sites1, occasionally beating daily newspapers in the actuality of most recent news. Be it the resignation of German national soccer team captain Philipp Lahm, or the downing of Malaysian Airlines flight 17 in the Ukraine by a guided missile, the corresponding Wikipedia page is updated as soon as the actual event happened (Becker 2012. -

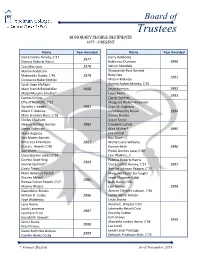

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

Presidents Worksheet 43 Secretaries of State (#1-24)

PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 43 NAME SOLUTION KEY SECRETARIES OF STATE (#1-24) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. 9,10,13 Daniel Webster 1 George Washington 2 John Adams 14 William Marcy 3 Thomas Jefferson 18 Hamilton Fish 4 James Madison 5 James Monroe 5 John Quincy Adams 6 John Quincy Adams 12,13 John Clayton 7 Andrew Jackson 8 Martin Van Buren 7 Martin Van Buren 9 William Henry Harrison 21 Frederick Frelinghuysen 10 John Tyler 11 James Polk 6 Henry Clay (pictured) 12 Zachary Taylor 15 Lewis Cass 13 Millard Fillmore 14 Franklin Pierce 1 John Jay 15 James Buchanan 19 William Evarts 16 Abraham Lincoln 17 Andrew Johnson 7, 8 John Forsyth 18 Ulysses S. Grant 11 James Buchanan 19 Rutherford B. Hayes 20 James Garfield 3 James Madison 21 Chester Arthur 22/24 Grover Cleveland 20,21,23James Blaine 23 Benjamin Harrison 10 John Calhoun 18 Elihu Washburne 1 Thomas Jefferson 22/24 Thomas Bayard 4 James Monroe 23 John Foster 2 John Marshall 16,17 William Seward PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 44 NAME SOLUTION KEY SECRETARIES OF STATE (#25-43) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. 32 Cordell Hull 25 William McKinley 28 William Jennings Bryan 26 Theodore Roosevelt 40 Alexander Haig 27 William Howard Taft 30 Frank Kellogg 28 Woodrow Wilson 29 Warren Harding 34 John Foster Dulles 30 Calvin Coolidge 42 Madeleine Albright 31 Herbert Hoover 25 John Sherman 32 Franklin D. -

THE SURGEON GENERAL and the BULLY PULPIT Michael Stobbe a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the University of North Carol

THE SURGEON GENERAL AND THE BULLY PULPIT Michael Stobbe A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Public Health in the Department of Health Policy and Administration, School of Public Health Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Ned Brooks Jonathan Oberlander Tom Ricketts Karl Stark Bryan Weiner ABSTRACT MIKE STOBBE: The Surgeon General and the Bully Pulpit (Under the direction of Ned Brooks) This project looks at the role of the U.S. Surgeon General in influencing public opinion and public health policy. I examined historical changes in the administrative powers of the Surgeon General, to explain what factors affect how a Surgeon General utilizes the office’s “bully pulpit,” and assess changes in the political environment and in who oversees the Surgeon General that may affect the Surgeon General’s future ability to influence public opinion and health. This research involved collecting and analyzing the opinions of journalists and key informants such as current and former government health officials. I also studied public documents, transcripts of earlier interviews and other materials. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES.................................................................................................................v Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................1 Background/Overview .........................................................................................1 -

1 April 2, 2020 the Honorable Nancy Pelosi Speaker, U.S. House Of

April 2, 2020 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi Speaker, U.S. House of Representatives H-232, United States Capitol Washington, DC 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi: We are grateful for your tireless work to address the needs of all Americans struggling during the COVID-19 pandemic, and for your understanding of the tremendous burdens that have been borne by localities as they work to respond to this crisis and keep their populations safe. However, we are concerned that the COVID-19 relief packages considered thus far have not provided direct funding to stabilize smaller counties, cities, and towns—specifically, those with populations under 500,000. As such, we urge you to include direct stabilization funding to such localities in the next COVID-19 response bill, or to lower the threshold for direct funding through the Coronavirus Relief Fund to localities with smaller populations. Many of us represent districts containing no or few localities with populations above 500,000. Like their larger neighbors, though, these smaller counties, cities, and towns have faced enormous costs while responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. These costs include deploying timely public service announcements to keep Americans informed, rapidly activating emergency operations, readying employees for telework to keep services running, and more. This work is essential to keeping our constituents safe and mitigating the spread of the coronavirus as effectively as possible. We fear that, without targeted stabilization funding, smaller localities will be unable to continue providing these critical services to our constituents at the rate they are currently. We applaud you for including a $200 billion Coronavirus Relief Fund as part of H.R. -

Aaron Ann Cole-Funfsinn

Good evening. I am honored to speak tonight on the post-election future of women’s leadership. This year and election have been unlike most others, for so many reasons, but for one, days after election day, we’re only now learning who the next President of the United States will be come January, and that we’ve finally elected the first woman, and woman of color, as Vice President. However, since you are all probably exhausted from election coverage, I want to instead focus my sermon on one of my professional heroes, the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg. As I’m sure you know, Justice Ginsberg served on the Supreme Court for 27 years, with her tenure ending with her death at sunset as Rosh Hashanah began. With all of the uncertainty we are facing right now, in politics and amidst a pandemic, I find comfort in looking to Justice Ginsberg’s lifetime of leadership and service to guide me, to guide us all, as we navigate forward, particularly past this divisive election. So this talk is organized around her quotes. Ruth Bader Ginsburg often said: “My mother told me to be a lady. And for her, that meant be your own person, be independent." My grandmother, my Bubbe, was Fannie Herman Miller. She taught at this Religious School for 45 years. And she was a lady. She raised four children as Jews here in Lexington during a time often as tumultuous as this one. At a time when most women worked in the home, she was a professor at the University of Kentucky, mentoring other women. -

Urban Policy in the Carter Administration

Urban Policy in the Carter Administration G. Thomas Kingsley Karina Fortuny May 2010 The What Works Collaborative is a foundation-supported research partnership that conducts timely research and analysis to help inform the implementation of an evidence-based housing and urban policy agenda. The Collaborative consists of researchers from the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program, Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, New York University’s Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, and the Urban Institute’s Center for Metropolitan Housing and Communities, as well as other experts from practice, policy, and academia. Support for the Collaborative comes from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Kresge Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Surdna Foundation. The Urban Institute is a nonprofit, nonpartisan policy research and educational organization that examines the social, economic, and governance problems facing the nation. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. URBAN POLICY IN THE CARTER ADMINISTRATION G. Thomas Kingsley and Karina Fortuny, the Urban Institute May 2010 In a July 2009 speech, President Obama stated that he has “directed the Office of Management and Budget, the Domestic Policy Council, the National Economic Council and the Office of Urban Affairs to conduct the first comprehensive interagency review in 30 years of how the federal government approaches and funds urban and metropolitan areas so that we can start having a concentrated, focused, strategic approach to federal efforts to revitalize our metropolitan areas.” This paper is the product of a rapid scan of available literature (and the memories of a few participants) to describe what actually happened 30 years ago as the Carter administration conducted that earlier review and policy formulation process. -

Twenty-Seventh Anniversary Awards Dinner

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu Twenty-Seventh Anniversary Awards Dinner Thursday, June 25, 1992 J. W. Marriott Hotel Washington, D.C. Page 1 of 30 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu CENTER FOR THE STUDY 0 PR Twenty-Seventh Anniversary Awards Dinner Thursday, June 25, 1992 J. W. Marriott Hotel Washington, D.C. Page 2 of 30 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu 1992 RECIPIENTS PROGRAM HONORABLE LLOYD BENTSEN United States Senate, (D) Texas PRESENTATION OF COLORS Since 1971, Lloyd Bentsen has served as a member of the United States The United States Armed Forces Joint Color Guard SenaterepresentingtheStateofTexas. During this time, the Senator served as Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee and as Vice Chairman of the Joint Committee on Taxation. He is a member of the Senate Commerce, NATIONAL ANTHEM Science and Trans1'9rtation Committee as well as the Joint Economic Virginia Drake, Baltimore Opera Company Committee. In 1988, Sena tor Bentsen was the Democratic Party nominee for Vice President of the United States. Senator Bentsen received a law degree from the University of Texas INVOCATION School of Law in 1942. Upon Graduation, he enlisted in the Army Air Forces, and earned the rank of Major as a B-24 pilot and Squadron Com- Richard C. Halverson, Chaplain mander. He was promoted to Colonel in the Air Force Reserve before United States Senate completing his military service. -

Congressional Record—Senate S

S 298 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð SENATE January 23, 1996 Government, but at least there has the welfare reform bill passed by the announcing my candidacy for the U.S. been agreement on that principle. Senate with overwhelming numbers, Senate on November 17, 1975, in the There is a substantial question as to some 87 Senators voting in favor of the first election cycle where the 1974 elec- whether the balanced budget proposal measure, there was a great deal of reli- tion law was in effect. At that time the offered by the administration meets ance on the block grants. There is an spending limitation applied to what an the ``fair'' criterion, since so much of it area for compromise on providing the individual could spend, and, for a State is deferred until the years 2001 and 2002. bulk of welfare related programs the size of Pennsylvania, it was $35,000. But I think there is ample room for ne- through block grants but certain spe- I decided to run for the office of U.S. gotiation, in order to have a realistic cific programs should remain with Senate against a very distinguished agreement made in those terms. standards established by the Federal American who later became a U.S. Sen- I spoke on this matter to some ex- Government. I think the statement ator, John Heinz. After my election in tent yesterday and wish to amplify it made by the very distinguished Sen- 1980, he and I formed a very close work- today. One set of figures which bear re- ator from Maine, Margaret Chase ing partnership and very close friend- peating are the statistics on the nar- Smith, is worth repeating, when she ship. -

Presidents Worksheet 43 Secretaries of State

PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 43 NAME ________________________________________ SECRETARIES OF STATE (#1-24) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. _____ Daniel Webster 1 George Washington 2 John Adams _____ William Marcy 3 Thomas Jefferson _____ Hamilton Fish 4 James Madison 5 James Monroe _____ John Quincy Adams 6 John Quincy Adams _____ John Clayton 7 Andrew Jackson 8 Martin Van Buren _____ Martin Van Buren 9 William Henry Harrison _____ Frederick Frelinghuysen 10 John Tyler 11 James Polk _____ Henry Clay (pictured) 12 Zachary Taylor _____ Lewis Cass 13 Millard Fillmore 14 Franklin Pierce _____ John Jay 15 James Buchanan _____ William Evarts 16 Abraham Lincoln 17 Andrew Johnson _____ John Forsyth 18 Ulysses S. Grant _____ James Buchanan 19 Rutherford B. Hayes 20 James Garfield _____ James Madison 21 Chester Arthur 22/24 Grover Cleveland _____ James Blaine 23 Benjamin Harrison _____ John Calhoun _____ Elihu Washburne _____ Thomas Jefferson _____ Thomas Bayard _____ James Monroe _____ John Foster _____ John Marshall _____ William Seward PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 44 NAME ________________________________________ SECRETARIES OF STATE (#25-43) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. _____ Cordell Hull 25 William McKinley _____ William Jennings Bryan 26 Theodore Roosevelt _____ Alexander Haig 27 William Howard Taft _____ Frank Kellogg 28 Woodrow Wilson 29 Warren Harding _____ John Foster Dulles 30 Calvin Coolidge _____ Madeleine Albright 31 Herbert Hoover _____ John Sherman 32 Franklin D. -

International Women's Forum

BERMUDA S CANA AMA DA AH ISRAEL B ND ITALY CH A ELA J IC RI IR AM AG ST NEW MEXICO AI O U IA SEY N C A D JER EW A IN W N TENNE YO C NE WEDE SSEE R J H IA S K O I L N TEX R LE A O A AI A N D R H D SP S O A T A A R N S D V TR TH C U I E IA IN O A N N C R ID K L O A A O F D R A G O LI O N R S N & A IC A L S A C T IN A D S O X O K É A S O N N B R A A G M E G K H N T N K R O C O U O E O A O N H O R www.iwforum.org C S T N T T U C U H N C R E A I O E I R K A K C R N N A E Y C T O I O Y I W C R C Z I M F A A U R A H L L T U A E I H N F B T O E I A U T R D R E N A O D N O A A S O N P I N L K A I A N L A I T N A H G N G N S G I E N O I D S L G S O H N O R I M D O O U A A E C I A S N L S I I I A S A A INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S FORUM WOMEN’S INTERNATIONAL U W T S W O T Y N U A N A K N A R H O L R A C A Celebrating 45 Years of Promoting Women’s Leadership Women’s Promoting of Years 45 Celebrating E M D H M , V H R O M N A E G M O I N A E R T G R A C C I U G N U O B U N S I E U O A T H V T O S S A I D E I S A R R P I O E W M G G M R V R A S O E E T R E O S M N A T N O S S E I N N A P I T O T E P G G W P N I A I P S H C G L A I P I H N H Y P S A U M S P I S E A A I S T E N P A S T C E V N L N Y I S T S N M A F I R M N A F I T C L O H S A I E G N A N N I M N T D S A O F C L N O U R S I D A A D I R F O L Table of Contents IWF History....................................................................................................1 Who We Are & What We Do...................................................................... -

List of Government Officials (May 2020)

Updated 12/07/2020 GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS PRESIDENT President Donald John Trump VICE PRESIDENT Vice President Michael Richard Pence HEADS OF EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENTS Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar II Attorney General William Barr Secretary of Interior David Bernhardt Secretary of Energy Danny Ray Brouillette Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Benjamin Carson Sr. Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao Secretary of Education Elisabeth DeVos (Acting) Secretary of Defense Christopher D. Miller Secretary of Treasury Steven Mnuchin Secretary of Agriculture George “Sonny” Perdue III Secretary of State Michael Pompeo Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross Jr. Secretary of Labor Eugene Scalia Secretary of Veterans Affairs Robert Wilkie Jr. (Acting) Secretary of Homeland Security Chad Wolf MEMBERS OF CONGRESS Ralph Abraham Jr. Alma Adams Robert Aderholt Peter Aguilar Andrew Lamar Alexander Jr. Richard “Rick” Allen Colin Allred Justin Amash Mark Amodei Kelly Armstrong Jodey Arrington Cynthia “Cindy” Axne Brian Babin Donald Bacon James “Jim” Baird William Troy Balderson Tammy Baldwin James “Jim” Edward Banks Garland Hale “Andy” Barr Nanette Barragán John Barrasso III Karen Bass Joyce Beatty Michael Bennet Amerish Babulal “Ami” Bera John Warren “Jack” Bergman Donald Sternoff Beyer Jr. Andrew Steven “Andy” Biggs Gus M. Bilirakis James Daniel Bishop Robert Bishop Sanford Bishop Jr. Marsha Blackburn Earl Blumenauer Richard Blumenthal Roy Blunt Lisa Blunt Rochester Suzanne Bonamici Cory Booker John Boozman Michael Bost Brendan Boyle Kevin Brady Michael K. Braun Anthony Brindisi Morris Jackson “Mo” Brooks Jr. Susan Brooks Anthony G. Brown Sherrod Brown Julia Brownley Vernon G. Buchanan Kenneth Buck Larry Bucshon Theodore “Ted” Budd Timothy Burchett Michael C.