Art Criticism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faculty Bios 2012

VACI Visual Arts at Chautauqua Institution Strohl Art Center, Chautauqua School of Art, Logan Galleries, Visual Arts Lecture Series ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Don Kimes/MANAGING DIRECTOR Lois Jubeck/GALLERY DIRECTOR Judy Barie ADVISORY COUNCIL TO THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: Michael Gitlitz, Director Marlborough Gallery, NYC - Judy Glantzman, Artist – Louis Grachos, Director Albright-Knox Gallery of Art - Donald Kuspit, Distinguished University Professor, SUNY Barbara Rose, Art Critic & Historian - Robert Storr, Dean, Yale School of Art Stephen Westfall, Artist & Critic Art In America - Julian Zugazoitia, Director Nelson Adkins Museum FACULTY AND VISITING ARTISTS (*partial listing – 3 additional faculty to be announced) Resident faculty (rf) teach from 2 to 7 weeks during the summer at Chautauqua. Visiting lecturers and faculty (vl, vf) are at Chautauqua for periods ranging from 1 to 3 days. PAINTING/SCULPTURE and PRINTMAKING TERRY ADKINS: Faculty, University of Pennsylvania Sculptor Terry Adkins teaches undergraduate and graduate sculpture. His work can be found I the collections of the Museum of Modern Art in NYC, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC, the Hood Museum at Dartmouth College, the Studio Museum in Harlem and many others. He has also taught at SUNY, New Paltz; Adkins has been the recipient of grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Joseph H. Hazen Rome Prize and was a USA James Baldwin Fellow, as well as the recipient of an Artist Exchange Fellowship, BINZ 39 Zurich and a residency at PS 1. Among many solo exhibitions of his work have been shows at Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH; Eastern State Penitentiary, Philadelphia, PA; Arthur Ross Gallery of the University of Pennsylvania, the Harn Museum of Art, the Cheekwood Museum of Art in Nashville, TN, John Brown House in Akron, Ohio, ICA in Philadelphia, PPOW Gallery, NY, the Whitney Museum at Philip Morris, NY, the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Anderson Gallery at VCU, Galerie Emmerich-Baumann in Zurich. -

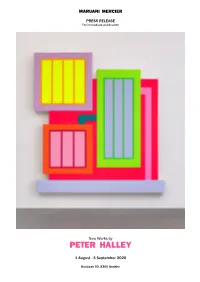

Peter Halley 2020

MARUANI MERCIER PRESS RELEASE For immediate publication New Works by PETER HALLEY 1 August - 3 September 2020 Kustlaan 90, 8300 Knokke MARUANI MERCIER is proud to announce their 9th exhibition with the American Neo-Conceptualist artist Peter Halley at their gallery in Knokke from 1 to 31 August 2020. Peter Halley was born in New York City in 1953. He received his BA from Yale University and his MFA from the University of New Orleans in 1978. Moving to New York City had big influence on Halley’s painting style. Its three-dimensional urban grid led to geometric paintings that engage in a play of relationships between so-called "prisons" and "cells" – icons that reflect the increasing geometricization of social space in the world. Halley began to use colors and materials with specific connotations, such as fluorescent Day-Glo paint, mimcking the eerie glow artificial lighting and reflective clothing and signs, as well as Roll-a-Tex, a texture additive used as surfacing in suburban buildings. Halley is part of the generation of Neo-Conceptualist artists that first exhibited in New York’s East Village, including Jeff Koons, Haim Steinbach, Mayier Vaisman and Ashley Bickerton. These artists became identified on a wider scale with the labels Neo-Geo and Neo-Conceptualism, an art practice deriving from the conceptual art movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Focussing on the commodification of art and its relation to gender, race, and class, neo-conceptualists question art and art institutions with irony and pastiche. Halley's works were included in the Sao Paolo Biennale, the Whitney Biennale and the 54th Venice Biennale and represented in such museums and art institutions as the CAPC Musee d'Art Contemporain, Bordeaux; the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid; the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; the Des Moines Art Center; The Tate Modern, London; the Dallas Museum of Art; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art; the Museum Folkwang, Essen and the Butler Institute of American Art. -

Personal Structures Culture.Mind.Becoming La Biennale Di Venezia 2013

PERSONAL STRUCTURES CULTURE.MIND.BECOMING LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA 2013 PALAZZO BEMBO . PALAZZO MORA . PALAZZO MARCELLO ColoPHON CONTENTS © 2013. Texts by the authors PERSONAL STRUCTURES 7 LAURA GURTON 94 DMITRY SHORIN 190 XU BINg 274 © If not otherwise mentioned, photos by Global Art Affairs Foundation PATRICK HAMILTON 96 NITIN SHROFF 192 YANG CHIHUNg 278 PERSONAL STRUCTURES: ANNE HERZBLUTh 98 SUH JEONG MIN 194 YE YONGQINg 282 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored THE ARTIsts 15 PER HESS 100 THE ICELANDIC YING TIANQI 284 in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, CHUL HYUN AHN 16 HIROFUMI ISOYA 104 LOVE CORPORATION 196 ZHANG FANGBAI 288 electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without YOSHITAKA AMANO 20 SAM JINKS 106 MONIKA THIELE 198 ZHANG GUOLONg 290 permission of the editor. ALICE ANDERSON 22 GRZEGORZ KLATKA 110 MICHELE TOMBOLINI 200 ZHANG HUAN 292 Jan-ERIK ANDERSSON 24 MEHdi-GeorGES LAHLOU 112 ŠtefAN TÓTh 202 ZHENG CHONGBIN 294 Print: Krüger Druck + Verlag, Germany AxEL ANKLAM 26 JAMES LAVADOUR 114 VALIE EXPORT 204 ZHOU CHUNYA 298 ATELIER MORALES 28 Edited by: Global Art Affairs Foundation HELMUT LEMKE 116 VITALY & ELENA VASIELIEV 208 INGRANDIMENTO 301 YIFAT BEZALEl 30 www.globalartaffairs.org ANNA LENZ 118 BEN VAUTIER 212 CHAILE TRAVEL 304 DJAWID BOROWER 34 LUCE 120 RAPHAEL VELLA 218 FAN ANGEl 308 FAIZA BUTT 38 Published by: Global Art Affairs Foundation ANDRÉ WAGNER 220 GENG YINI 310 GENIA CHEF 42 MICHELE MANZINI 122 in cooperation with Global Art Center -

Review of Ernest Samuels, Bernard Berenson: the Making of A

Reviews The Russell-Berenson connection by Andrew Brink Ernest Samuels. Bernard Berenson: The Making of a Connoisseur. Cam bridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1979. Pp. xviii, 477; 30 plates. US$15.00. C$18.75. BERNARD BERENSON AND Bertrand Russell were of contrary tempera ments, yet they were attracted to form a more than passing friendship. Berenson came into Russell's orbit by marriage to Mary Costelloe, the older sister of Russell's first wife, Alys Pearsall Smith. During his time in the British diplomatic service in Paris in 1894 Russell enjoyed Mary's enliven ing company. Her free spirit delighted him, and she figures frequently as Mariechen in the love correspondence with Alys. Until Ernest Samuels's biography of Berenson it has been difficult to picture this Philadelphia Quaker turned art critic and supporter of the most celebrated art expert of the century. Samuels's study gives her a vivid presence in the international set to which she belonged-a woman ofdrive and ingenuity without whom Berenson wouldn't have become the legend he was. Samuels stays close to the very full correspondences which constitute detailed documentation of their lives together. He interprets little, allowing the record to speak for itself. We hear in detail of the breakdown of Mary's marriage to Frank Costelloe, of tensions with her mother, ofloyalty to her two daughters and ofthe difficulties ofkeeping peace with Berenson. Stresses and tempests are not hidden. There are attractions to other men, Mary taking advantage of new sexual freedoms in the set she joined, freedoms which Berenson's firmer conscience forbade. -

Excerpted from Bernard Berenson and the Picture Trade

1 Bernard Berenson at Harvard College* Rachel Cohen When Bernard Berenson began his university studies, he was eighteen years old, and his family had been in the United States for eight years. The Berensons, who had been the Valvrojenskis when they left the village of Butrimonys in Lithuania, had settled in the West End of Boston. They lived near the North Station rail yard and the North End, which would soon see a great influx of Eastern European Jews. But the Berensons were among the early arrivals, their struggles were solitary, and they had not exactly prospered. Albert Berenson (fig. CC.I.1), the father of the family, worked as a tin peddler, and though he had tried for a while to run a small shop out of their house, that had failed, and by the time Berenson began college, his father had gone back to the long trudging rounds with his copper and tin pots. Berenson did his first college year at Boston University, but, an avid reader and already a lover of art and culture, he hoped for a wider field. It seems that he met Edward Warren (fig. CC.I.16), with whom he shared an interest in classical antiquities, and that Warren generously offered to pay the fees that had otherwise prevented Berenson from attempting to transfer to Harvard. To go to Harvard would, in later decades, be an ambition of many of the Jews of Boston, both the wealthier German and Central European Jews who were the first to come, and the poorer Jews, like the Berensons, who left the Pale of Settlement in the period of economic crisis and pogroms.1 But Berenson came before this; he was among a very small group of Jewish students, and one of the first of the Russian Jews, to go to Harvard. -

The Leading International Forum for Literary Culture

The leading international forum for literary culture Connoisseur BRUCE BOUCHER Rachel Cohen BERNARD BERENSON A life in the picture trade 328pp. Yale University Press. £18.99 (US $25). 978 0 300 14942 5 BERNARD BERENSON Formation and heritage 440pp.Villa I Tatti: The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies. Paperback, £29.95 (US $40). 978 0 674 42785 3 Published: 29 October 2014 O scar Wilde gave Bernard Berenson one of the first copies of The Picture of Dorian Gray, which the young man read overnight. He subsequently told Wilde “how loathsome, how horrible” the booK seemed; evidently, the story of the secret bond between a handsome young man and his festering portrait touched a nerve. It also seemed to prophesy the uneasiness the older Berenson would feel about the disparity between his aims as a scholar and the Faustian bargain he strucK to maKe money from art dealers and their clients. For over half a century, he used connoisseurship to establish the contours of Italian Renaissance painting, writing with great sensitivity about artists as diverse as Lorenzo Lotto and Piero della Francesca. He popularized the concept of “tactile values” and the life-enhancing nature of great art. A refugee from the Pale of Settlement in Czarist Russia, Berenson transformed himself into a worK of art, holding court at his villa outside Florence where aristocracy and the intelligentsia clamoured to visit; yet he judged himself a failure. Bernard Berenson: A life in the picture trade appears as part of a series called Jewish Lives, a heading that would probably have puzzled its subject. -

The Letters of George Santayana Book Two, 1910—1920

The Letters of George Santayana Book Two, 1910—1920 To Josephine Preston Peabody Marks [1910 or 1911] • Cambridge, Massachusetts (MS: Houghton) COLONIAL CLUB CAMBRIDGE Dear Mrs Marks1 Do you believe in this “Poetry Society”? Poetry = solitude, Society = prose, witness my friend Mr. Reginald Robbins!2 I may still go to the dinner, if it comes during the holidays. In that case, I shall hope to see you there. Yours sincerely GSantayana 1Josephine Preston Peabody (1874–1922) was a poet and dramatist whose plays kept alive the tradition of poetic drama in America. Her play, The Piper, was produced in 1909. She was married to Lionel Simeon Marks, a Harvard mechanical engineering professor. 2Reginald Chauncey Robbins (1871–1955) was a writer who took his A.B. from Harvard in 1892 and then did graduate work there. To William Bayard Cutting Sr. [January 1910] • [Cambridge, Massachusetts] (MS: Unknown) His intellectual life was, without question, the most intense, many-sided and sane that I have ever known in any young man,1 and his talk, when he was in college, brought out whatever corresponding vivacity there was in me in those days, before the routine of teaching had had time to dull it as much as it has now … I always felt I got more from him than I had to give, not only in enthu- siasm—which goes without saying—but also in a sort of multitudinousness and quickness of ideas. [Unsigned] 1William Bayard Cutting Jr. (1878–1910) was a member of the Harvard class of 1900. He served as secretary of the vice consul in the American consulate in Milan (1908–9) and Secretary of the American Legation, Tangier, Morocco (1909). -

Peter Halley

PETER HALLEY BIOGRAPHY 1953 Born in New York City 1971 Graduates from Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts 1975 Studies at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 1976 Moves to New Orleans 1978 Studies at University of New Orleans 1980 Moves to New York City 1981 Publishes ‘Beat, Minimalism, New Wave, and Robert Smithson’, the first of six essays to appear in Arts Magazine, New York 1985 Solo exhibition at International with Monument, New York 1989 Solo exhibition at the Museum Haus Esters, Krefeld, Germany 1991 Retrospective at CAPC Musée d’art contemporain, Bordeaux. Exhibition tours to FAE Musée d’art contemporain, Pully/Lausanne, the Reina Sofía, Madrid, and the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam 1995 First large-scale installation at the Dallas Museum of Art 1996 Founds index, a bi-monthly magazine covering independent culture. Publishes index until 2005 1996-99 Serves as Adjunct Professor, U.C.L.A., School of Art and Architecture, Los Angeles 1997 New Concepts of Printmaking 1: Peter Halley at the Museum of Modern Art, New York 1999 Appointed Senior Lecturer in Painting, Yale University, School of Art, New Haven, Connecticut 2000 Begins teaching as Adjunct Professor, Columbia University, New York City 2001 Receives the annual Frank Jewett Mather Award for published art criticism from the College Art Association 2002 Appointed Director of Graduate Studies in Painting and Printmaking at the Yale University School of Art, until 2011 Permanent installation of wall-size digital prints at the public library in Usera, Spain, commissioned -

Peter Halley Paintings of the 1980S the Catalogue Raisonné Cara Jordan Table of Contents

Peter Halley Paintings of the 1980s The Catalogue Raisonné Cara Jordan Table of Contents Introduction 4 Cara Jordan Facts Are Useless in Emergencies 6 Paul Pieroni Guide to the Catalogue Raisonné 11 Catalogue Raisonné Peter Halley in front of his first New York studio at 128 East 7th Street, 1985 1980 13 1981 23 1982 37 1983 47 1984 59 1985 67 1986 93 1987 125 1988 147 1989 167 Appendix Biography 187 Solo Exhibitions 1980–1989 188 Group Exhibitions 1980–1989 190 Introduction Cara Jordan The publication of this catalogue raisonné of Peter Halley’s through a diagrammatic representation of space. His paintings French Post-Structuralist theorists such as Michel Foucault and and SCHAUWERK Sindelfingen; and the numerous galleries paintings from the 1980s offers a significant opportunity to reflect transformed the paradigmatic square of abstract art into refer- Jean Baudrillard to the North American art world—emphatically and art dealers who have supported Halley’s work throughout on the early works and career of one of the most well-known en tial icons that he labeled “prisons” and “cells,” and linked them refuted the traditional humanist and spiritual aspirations of art.1 the years, including Thomas Ammann Fine Art AG, Galerie artists of the Neo-Conceptualist generation. It was during these by means of straight lines he called “conduits.” Through this His writings described the shifting relationship between the Bruno Bischofberger, Galerie Andrea Caratsch, Greene Naftali years that Halley developed the hallmark iconography and formal simple icono graphy, which remains the basis of Halley’s visual individual and larger social structures triggered by technology Gallery, Margo Leavin Gallery, Galería Javier López & Fer language of his paintings, which connected the tradition of language, he created a compartmentalized space connected by and the digital revolution, leading critic Paul Taylor to name Francés, Maruani Mercier Gallery, and Sonnabend Gallery. -

Research on the Characteristics of Abstract Painting

2020 8th International Education, Economics, Social Science, Arts, Sports and Management Engineering Conference (IEESASM 2020) Research on the Characteristics of Abstract Painting Luomin Pan Graduate School of Namseoul University, Cheonan 31020, Korea [email protected] Keywords: Abstract painting, Light and color, Music, Space Abstract: This article analyzes the painting works of the representative artists of the AbstractSchool and the New AbstractSchool, and conducts an Expandability research on the characteristics of Abstractpainting. The first part, “The Confusion of Light and Color”, is to understand the color of “multi-personality” from a new perspective. Color does not have immutable meanings forever. The signs of color depend on the artist's creative intentions. The second part, “The Musical Sense of AbstractPainting”, analyzes the musicality of painting through points, lines and surfaces. The musicality of painting allows us to think about more possibilities in the parallel world of painting and music. The third part “Reconstruction of Space” analyzes the multi-dimensional space of Abstractpainting, the indifferent two-dimensional space between two-dimensional and three-dimensional, the multi-dimensional space in two-dimensional and the new space. The study of painting space is an important proposition of Abstractpainting. The author hopes to explore the characteristics of Abstractpainting to inspire us how to deal with old things and old topics, to make new thinking, and to provide more templates for artistic creation and thinking on easel. 1. Introduction The light and color in painting is a basic concept. Only when there is light, there is color. The color we are discussing here refers to the color of painting, and light is the premise of its appearance. -

School of Art 2006–2007

ale university May 10, 2006 2007 – Number 1 bulletin of y Series 102 School of Art 2006 bulletin of yale university May 10, 2006 School of Art Periodicals postage paid New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8227 ct bulletin of yale university bulletin of yale New Haven Bulletin of Yale University The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and affirmatively seeks to Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, attract to its faculty, staff, and student body qualified persons of diverse backgrounds. In PO Box 208227, New Haven ct 06520-8227 accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against any individual on PO Box 208230, New Haven ct 06520-8230 account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, status as a special disabled Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut veteran, veteran of the Vietnam era, or other covered veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. Issued seventeen times a year: one time a year in May, November, and December; two times University policy is committed to affirmative action under law in employment of women, a year in June; three times a year in July and September; six times a year in August minority group members, individuals with disabilities, special disabled veterans, veterans of the Vietnam era, and other covered veterans. Managing Editor: Linda Koch Lorimer Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valerie O. -

JENNIFER BARTLETT Painting the Language of Nature and Painting

JENNIFER BARTLETT Painting The Language Of Nature And Painting October 6–November 11, 2006 Essay by Donald Kuspit It’s Really Beautiful , 2003 enamel over silkscreen grid on baked enamel, steel plate 50 x 50 centimeters (19.7 x 19.7 inches) 5 Jennifer Bartlett: Painting The Language Of Nature And Painting Donald Kuspit “The belief system of the old language of painting had collapsed,” declared Joseph Kosuth, one of the founding figures of Conceptualism or Idea Art. This supposedly happened in the sixties, when Conceptualism, among other anti-paint - ing movements, appeared on the scene. It is why Kosuth “chose language for the ‘material’ of my work because it seemed to be the only possibility with the poten - tial for being a neutral non-material.”(1) (Painting of course died before the six - ties. It was stabbed to death, the way Brutus stabbed Caesar, by Marcel Duchamp’s anti-painting Tu’m , 1918, and buried alive in Alexander Rodchenko’s Last Paintings , 1921. Painting has been mourning for itself ever since, as some critics think, although it is not clear that its corpse has begun to decompose.) So what are we to make of Jennifer Bartlett’s new works, which use both the old language of painting and the neutral non-material of language? Is she trying to renew painting, suggesting that it still has something to say that can be said in no other language? Is her work part of the post-Conceptual resurgence of painting announced by the “New Painting” exhibition held in London in 1981? Or does she intend to remind us that language is not a neutral non-material, however neutral it seems, for it communicates concepts, which are an intellectual material, and always slippery – elusive even in everyday use, which assumes understanding of them? If one didn’t, how is one to get on with the everyday business of life – life in the country, on the seashore – which is what Bartlett’s works deal with.