Motherwell's Open: Heidegger, Mallarmé And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BLACK Baselitz, De Kooning, Mariscotti, Motherwell, Serra

Upsilon Gallery 404 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018 [email protected] www.upsilongallery.com For immediate release BLACK Baselitz, de Kooning, Mariscotti, Motherwell, Serra April 13 – June 3, 2017 Curated by Marcelo Zimmler Spanish Elegy I, Lithograph, on brown HMP handmade paper, 13 3/4 x 30 7/8 in. (35 x 78.5 cm), 1975. Photo by Caius Filimon Upsilon Gallery is pleased to present Black, an exhibition of original and edition work by Georg BaselitZ, Willem de Kooning, Osvaldo Mariscotti, Robert Motherwell and Richard Serra, on view at 146 West 57 Street in New York. Curated by Marcelo Zimmler, the exhibition explores the role played by the color black in Post-war and Contemporary work. In the 1960s, Georg BaselitZ emerged as a pioneer of German Neo–Expressionist painting. His work evokes disquieting subjects rendered feverishly as a means of confronting the realities of the modern age, and explores what it is to be German and a German artist in a postwar world. In the late 1970s his iconic “upside-down” paintings, in which bodies, landscapes, and buildings are inverted within the picture plane ignoring the realities of the physical world, make obvious the artifice of painting. Drawing upon a dynamic and myriad pool of influences, including art of the Mannerist period, African sculptures, and Soviet era illustration art, BaselitZ developed a distinct painting language. Upsilon Gallery 404 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018 [email protected] www.upsilongallery.com Willem de Kooning was born on April 24, 1904, into a working class family in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. -

Faculty Bios 2012

VACI Visual Arts at Chautauqua Institution Strohl Art Center, Chautauqua School of Art, Logan Galleries, Visual Arts Lecture Series ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Don Kimes/MANAGING DIRECTOR Lois Jubeck/GALLERY DIRECTOR Judy Barie ADVISORY COUNCIL TO THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: Michael Gitlitz, Director Marlborough Gallery, NYC - Judy Glantzman, Artist – Louis Grachos, Director Albright-Knox Gallery of Art - Donald Kuspit, Distinguished University Professor, SUNY Barbara Rose, Art Critic & Historian - Robert Storr, Dean, Yale School of Art Stephen Westfall, Artist & Critic Art In America - Julian Zugazoitia, Director Nelson Adkins Museum FACULTY AND VISITING ARTISTS (*partial listing – 3 additional faculty to be announced) Resident faculty (rf) teach from 2 to 7 weeks during the summer at Chautauqua. Visiting lecturers and faculty (vl, vf) are at Chautauqua for periods ranging from 1 to 3 days. PAINTING/SCULPTURE and PRINTMAKING TERRY ADKINS: Faculty, University of Pennsylvania Sculptor Terry Adkins teaches undergraduate and graduate sculpture. His work can be found I the collections of the Museum of Modern Art in NYC, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC, the Hood Museum at Dartmouth College, the Studio Museum in Harlem and many others. He has also taught at SUNY, New Paltz; Adkins has been the recipient of grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Joseph H. Hazen Rome Prize and was a USA James Baldwin Fellow, as well as the recipient of an Artist Exchange Fellowship, BINZ 39 Zurich and a residency at PS 1. Among many solo exhibitions of his work have been shows at Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH; Eastern State Penitentiary, Philadelphia, PA; Arthur Ross Gallery of the University of Pennsylvania, the Harn Museum of Art, the Cheekwood Museum of Art in Nashville, TN, John Brown House in Akron, Ohio, ICA in Philadelphia, PPOW Gallery, NY, the Whitney Museum at Philip Morris, NY, the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Anderson Gallery at VCU, Galerie Emmerich-Baumann in Zurich. -

Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1988 The Politics of Experience: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s Maurice Berger Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1646 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

FY 15 ANNUAL REPORT August 1, 2014- July 31, 2015

FY 15 ANNUAL REPORT August 1, 2014- July 31, 2015 1 THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION FY15 Annual Report THE PHILLIPS [IS] A MULTIDIMENSIONAL INSTITUTION THAT CRAVES COLOR, CONNECTEDNESS, A PIONEERING SPIRIT, AND PERSONAL EXPERIENCES 2 THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION FY15 Annual Report FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND DIRECTOR This is an incredibly exciting time to be involved with The Phillips Collection. Duncan Phillips had a deep understanding of the “joy-giving, life-enhancing influence” of art, and this connection between art and well-being has always been a driving force. Over the past year, we have continued to push boundaries and forge new paths with that sentiment in mind, from our art acquisitions to our engaging educational programming. Our colorful new visual identity—launched in fall 2014—grew out of the idea of the Phillips as a multidimensional institution, a museum that craves color, connectedness, a pioneering spirit, and personal experiences. Our programming continues to deepen personal conversations with works of art. Art and Wellness: Creative Aging, our collaboration with Iona Senior Services has continued to help participants engage personal memories through conversations and the creating of art. Similarly, our award-winning Contemplation Audio Tour encourages visitors to harness the restorative power of art by deepening their relationship with the art on view. With Duncan Phillips’s philosophies leading the way, we have significantly expanded the collection. The promised gift of 18 American sculptors’ drawings from Trustee Linda Lichtenberg Kaplan, along with the gift of 46 major works by contemporary German and Danish artists from Michael Werner, add significantly to new possibilities that further Phillips’s vision of vital “creative conversations” in our intimate galleries. -

76 Jefferson Fall Penthouse Art Lending Service Exhibition

The Museum of Modern Art U West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart FOR RELEASE: SEPTEMBER 11, 1975 76 JEFFERSON FALL PENTHOUSE ART LENDING SERVICE EXHIBITION 76 JEFFERSON, an exhibition of 38 works produced at that Lower East Side New York address, is the Fall Penthouse exhibition of the Art Lending Service of The Museum of Modern Art, and will be on view from September 11 through December 1. Because of the large number of artists who have lived and worked in the building, the group of works reflects the diversity of art produced in New York 'during the last 15 years. Works by 18 artists in a variety of styles and mediums are included — abstract and realistic painting, sculpture in various materials, and drawings and prints. In addition, there are silkscreen prints published by Chiron Press, which was also located at 76 Jefferson Street from 1963 to 1967. The exhibition has been organized by Richard Marshall, se lections advisor to the Museum's Art Lending Service, and all of the works are for sale. The artists represented in the exhibition who lived and/or worked at 76 Jefferson Street are Milet Andrejevic, E. H. Davis, John Duff, Mel Edwards, Janet Fish, Valerie Jaudon, Neil Jenney, Richard Kalina, Kenneth Kilstrom, Kobashi, Robert Lobe, Brice Marden, Robert Neuwirth, Steve Poleskie, David Robinson, Ed Shostak, Gary Stephan and Neil Williams. The artists whose Chiron Press prints will be on view are Richard Anuskiewicz, Allan d'Arcangelo, Jim Dine, Rosalyn Drexler, Al Held, Robert Indiana, Alex Katz, Ellsworth Kelly, Nicholas Krushenick, Marisol, Robert Motherwell, Louise Nevelson, James Rosenquist, Saul Steinberg, Ernest Trova, Andy Warhol, Jack Youngerman, and Larry Zox. -

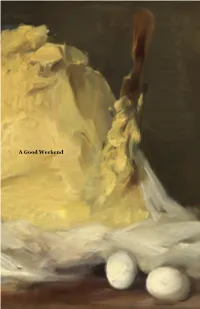

A Good Weekend Cookbook

A Good Weekend A Good Weekend Cookbook Recipes for Various Sweets—and One Potent Cocktail—That Artists Have Created, Utilized, or Simply Enjoyed Over the Past 100 Years Compiled by Andrew Russeth Table of Contents Latifa Echakhch Madeleines au miel 01 Mimi Stone Olive Oil Cake 02 Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec… Rum Punch, Rum Tarte… 04 Mary Cassatt Caramels au Chocolat 06 Norman Rockwell Oatmeal Cookies 07 Grandma Moses Old-Fashioned Macaroons 08 John Cage Almond Cookies 09 Charles Sheeler Shoo-Fly Cake, Molasses Shoo… 10 Roger Nicholson Gunpowder Cake 12 Grant Wood Strawberry Shortcake 13 Karel Appel Cake Barber 15 Sam Francis Schaum Torte 16 Jean Tinguely Omelette Soufflé Dégonflé… 17 Rella Rudoplh Sesame Cookies 18 Frida Kahlo Shortbread Cookies 19 Romare Bearden Bolo Di Rom 20 Richard Estes Aunt Fanny’s English Toffee 22 Alex Katz Sandwich List 23 Robert Motherwell Robert’s Whiskey Cake… 24 Alice Neel Hot-Fudge Sauce 26 George Segal Sponge Cake 27 Tom Wesselmann Banana-Pineapple Bread… 28 An Introduction Since coming across John Cage’s recipe for almond cookies on Greg Allen’s blog a few years ago, I’ve collected recipes associated with artists—dishes they invented, cooked, or just enjoyed—and, much to my surprise, the list has grown quite long. There’s a treasure trove out there! A few examples: Robert Motherwell made rich bittersweet chocolate mousse. Romare Bearden used an old recipe from St. Martin to cook up rum cake. “I don’t do much cooking,” Alice Neel said in 1977. “I’m an artist; I have privileges, you see, that only men had in the past." But she did have a choice recipe for hot-fudge sauce. -

Hartford, Connecticut R EPORT

W ADSWORTH A THENEUM M USEUM OF A RT 2009 A NNUAL R EPORT Hartford, Connecticut R EPORT from the President In 1932, in the midst of the Great Depression, A Everett Austin, Jr. opined that All tenses of time conjoin at the Wadsworth Atheneum, an institution “…the appreciation of works of art serves…to allay for some moments the which continuously honors its historic past, while living in the present and worry and anxiety in which we all share.” It is uplifting to know that over the planning for the future. As we continue to devise both short and long term strate - past twelve months, when the world experienced a challenging financial collapse, gies to preserve our financial stability and enhance the museum’s position as a the gravity of which has not been witnessed since the 1930s, the Wadsworth cultural leader both locally and internationally, we remain fully committed to Atheneum continued as a thriving and stable institution, ensuring that the the constituents who help make our visions a reality through their unwavering lega cy we leave to future generations will be a strong one. support. At the outset of the crisis, the museum implemented swift budgetary To all of the members, friends, patrons, and devotees of this museum— measures in a determined effort to reduce costs. Despite these difficult meas - you have my sincere gratitude. I encourage you to maintain your vital support ures, we remained committed to our artistic mission and to upholding the trust —particularly now, as institutions like ours play a critical role as a place of per - placed in us by our community. -

Fourteen Americans Edited by Dorothy C

Fourteen Americans Edited by Dorothy C. Miller, with statements by the artists and others Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1946 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3196 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art it iii EFT. fhetxiftt fourteen americans aronson culwell gorky hare maciver motherwell noguchi pereira pickens price roszak sharrer Steinberg tobey fourteen americans EDITED BY DOROTHY C. MILLER with statements by the artists and others THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Copyright 1946. The Museum of Modern Art. Printed in the U.S.A. 4 . ft'l 9 M f) fir contents page FOREWORD 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENT 9 david aronson 10 ben I. culwell 15 arshile gorky 20 david hare 24 loren maciver 28 robert motherwell 34 isamu noguchi 39 i. rice pereira 44 alt on pickens 49 c. s. price .54 theodore j. roszak 58 honore sharrer 62 said Steinberg 66 mark tobey 70 LENDERS TO THE EXHIBITION 76 CATALOG OF THE EXHIBITION 76 TRUSTEES OF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART John Hay Whitney, Chairman of the Board; Henry Allen Moe, ist Vice-Chairman; Philip L. Goodwin, 2nd Vice-Chairman; Sam A. Lewisohn, yd Vice-Chairman; Nelson A. Rockefeller, President; John E. Abbott, Vice-President and Secretary; Ranald H. Macdonald, Treasurer; Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, William A. M. Burden, Stephen C. -

Contemporary Art Collection Teacher’S Curriculum Guide

Contemporary Art Collection Teacher’s Curriculum Guide © Estate of Al Held. Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY Rome II, 1982 Al Held TABLE OF CONTENTS How to Use These Materials……….…………………………………………………………………………..…..……………….…………3 A Brief History..........……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………….4 Abstract Expressionism.……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….….5 Color, Signs, & Geometry……………………………………………………………………….……………….………………………………6 New Materials…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…………….7 Curriculum Connections…………………………………………………..……………………………………………………………………..8 Glossary……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..………………………….10 Appendix……………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………11 • I Am For An Art, Claes Oldenburg • Autoportrait Templates • Autobiography vs. Self-Portrait Image Credits…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………17 Works Consulted……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………18 NOTICE: Several works of art in the Delaware Art Museum’s collection contain partial or full nudity. While we maintain the artistic integrity of these pieces and do not encourage censorship we have marked these pieces in an effort to provide educators with pertinent information. You will see a green inverted triangle ( ) next to any works that contain partial or full nudity, or mature content. This packet is intended for educators; please preview all materials before distributing to your class. 2 HOW TO USE THESE MATERIALS These materials are designed to provide teachers with an overview of the artists -

Robert Motherwell's Elegies to the Spanish Republic

Was there a myth in the making?-A Structuralist Approach to Robert Motherwell's Elegies to the Spanish Republic Alice S. Brooker In 1948 Robert Motherwell created a small abstract to paint accordingly; rathe~ the intuitive, expressive expe drawing in black and white to illustrate a poem by Harold rience of painting became, for him, constantly interwoven Rosenberg. Motherwell had planned to publish this draw with a modifying intellectual strain.• ing in the second edition of Possibililies' (Figure I). When It was from the Surrealists' priociple of psychic autom the edition was not published, he put the drawing away and atism that Motherwell found his original inspiration for the forgot about it. Then, in 1949, Motherwell rediscovered the Spanish Elegies series. Like the Surrealists, Motherwell was piece while cleaning out a drawer. Now realizing that the fascinated with the concept of tapping into the subconscious; tension created by the reduced palette of black and white but for him, it was not merely to unearth such things as was echoed in the interplay between the sensuous ovals and Freudian symbols of repressed sexuality. Rathe~ as Jack D. thick, assertive rectangles, he reworked the original drawing Aam states in his 1983 publication on Motherwell, it was to into a small painting which he titled At Five in the discover•. .. a language that could adequately express com Afternoon. He took the new title from a line in a poem by plex physical and metaphysical realities.• , Federico Garcia Lorca2 (Figure 2). Following the SurrealiSts' methods, Motherwell used Although small in scale (15' x 20"), the new painting automatic "doodling" to create elementary forms which he was pivotal for Motherwell's artistic development. -

School of Art 2006–2007

ale university May 10, 2006 2007 – Number 1 bulletin of y Series 102 School of Art 2006 bulletin of yale university May 10, 2006 School of Art Periodicals postage paid New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8227 ct bulletin of yale university bulletin of yale New Haven Bulletin of Yale University The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and affirmatively seeks to Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, attract to its faculty, staff, and student body qualified persons of diverse backgrounds. In PO Box 208227, New Haven ct 06520-8227 accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against any individual on PO Box 208230, New Haven ct 06520-8230 account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, status as a special disabled Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut veteran, veteran of the Vietnam era, or other covered veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. Issued seventeen times a year: one time a year in May, November, and December; two times University policy is committed to affirmative action under law in employment of women, a year in June; three times a year in July and September; six times a year in August minority group members, individuals with disabilities, special disabled veterans, veterans of the Vietnam era, and other covered veterans. Managing Editor: Linda Koch Lorimer Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valerie O. -

Robert Motherwell and Harvard with the Intention of Becoming a Philosopher

Motherwell was born in Aberdeen, Washington and studied at Stanford Robert Motherwell and Harvard with the intention of becoming a philosopher. He was in- Artist ( 1915 – 1991 ) fluenced by Alfred North Whitehead, who first challenged him with the notion of abstraction, and when Motherwell moved to New York in 1940 he took that sensibility with him. Motherwell lived in Greenwich Village where he joined a group of art- ists—including Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko and Franz Kline—who set out to change the face of American painting. These artists renounced the prevalent American style, believing its real- ism depicted only the surface of American life. Influenced by the Sur- realists, many of whom had emigrated from Europe to New York, the Abstract Expressionists sought to create essential images that revealed emotional truth and authenticity of feeling. These early years were an incredibly productive period for Motherwell and he experimented in a range of media, from painting to printmak- ing to collage. His work often expressed the actions of the artist through dramatic and bright brush strokes. Valued for their energetic imagery, they attempted a pure emotional response made real in paint. Beyond his individual efforts as an artist, Motherwell played a major role in the intellectual and artistic development of the underground New York art world. A serious art historian, Motherwell founded the Documents of Art series. Reflecting on those early years, he spoke of their belief that “if the ab- straction, the violence, the humanity was valid in Abstract Expression- ism, then it cut out the ground from every other kind of painting.” With the advent of Pop Art and its concentration on popular culture themes, the art public began to long for the idealism of the Abstract Expression- ists.