Jeff Koons: One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

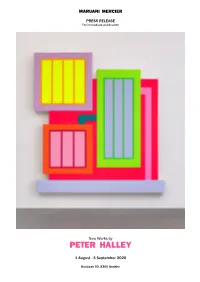

Peter Halley 2020

MARUANI MERCIER PRESS RELEASE For immediate publication New Works by PETER HALLEY 1 August - 3 September 2020 Kustlaan 90, 8300 Knokke MARUANI MERCIER is proud to announce their 9th exhibition with the American Neo-Conceptualist artist Peter Halley at their gallery in Knokke from 1 to 31 August 2020. Peter Halley was born in New York City in 1953. He received his BA from Yale University and his MFA from the University of New Orleans in 1978. Moving to New York City had big influence on Halley’s painting style. Its three-dimensional urban grid led to geometric paintings that engage in a play of relationships between so-called "prisons" and "cells" – icons that reflect the increasing geometricization of social space in the world. Halley began to use colors and materials with specific connotations, such as fluorescent Day-Glo paint, mimcking the eerie glow artificial lighting and reflective clothing and signs, as well as Roll-a-Tex, a texture additive used as surfacing in suburban buildings. Halley is part of the generation of Neo-Conceptualist artists that first exhibited in New York’s East Village, including Jeff Koons, Haim Steinbach, Mayier Vaisman and Ashley Bickerton. These artists became identified on a wider scale with the labels Neo-Geo and Neo-Conceptualism, an art practice deriving from the conceptual art movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Focussing on the commodification of art and its relation to gender, race, and class, neo-conceptualists question art and art institutions with irony and pastiche. Halley's works were included in the Sao Paolo Biennale, the Whitney Biennale and the 54th Venice Biennale and represented in such museums and art institutions as the CAPC Musee d'Art Contemporain, Bordeaux; the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid; the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; the Des Moines Art Center; The Tate Modern, London; the Dallas Museum of Art; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art; the Museum Folkwang, Essen and the Butler Institute of American Art. -

Personal Structures Culture.Mind.Becoming La Biennale Di Venezia 2013

PERSONAL STRUCTURES CULTURE.MIND.BECOMING LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA 2013 PALAZZO BEMBO . PALAZZO MORA . PALAZZO MARCELLO ColoPHON CONTENTS © 2013. Texts by the authors PERSONAL STRUCTURES 7 LAURA GURTON 94 DMITRY SHORIN 190 XU BINg 274 © If not otherwise mentioned, photos by Global Art Affairs Foundation PATRICK HAMILTON 96 NITIN SHROFF 192 YANG CHIHUNg 278 PERSONAL STRUCTURES: ANNE HERZBLUTh 98 SUH JEONG MIN 194 YE YONGQINg 282 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored THE ARTIsts 15 PER HESS 100 THE ICELANDIC YING TIANQI 284 in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, CHUL HYUN AHN 16 HIROFUMI ISOYA 104 LOVE CORPORATION 196 ZHANG FANGBAI 288 electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without YOSHITAKA AMANO 20 SAM JINKS 106 MONIKA THIELE 198 ZHANG GUOLONg 290 permission of the editor. ALICE ANDERSON 22 GRZEGORZ KLATKA 110 MICHELE TOMBOLINI 200 ZHANG HUAN 292 Jan-ERIK ANDERSSON 24 MEHdi-GeorGES LAHLOU 112 ŠtefAN TÓTh 202 ZHENG CHONGBIN 294 Print: Krüger Druck + Verlag, Germany AxEL ANKLAM 26 JAMES LAVADOUR 114 VALIE EXPORT 204 ZHOU CHUNYA 298 ATELIER MORALES 28 Edited by: Global Art Affairs Foundation HELMUT LEMKE 116 VITALY & ELENA VASIELIEV 208 INGRANDIMENTO 301 YIFAT BEZALEl 30 www.globalartaffairs.org ANNA LENZ 118 BEN VAUTIER 212 CHAILE TRAVEL 304 DJAWID BOROWER 34 LUCE 120 RAPHAEL VELLA 218 FAN ANGEl 308 FAIZA BUTT 38 Published by: Global Art Affairs Foundation ANDRÉ WAGNER 220 GENG YINI 310 GENIA CHEF 42 MICHELE MANZINI 122 in cooperation with Global Art Center -

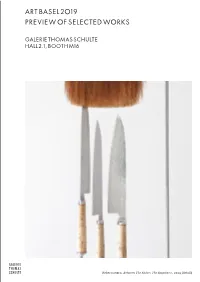

Art Basel 2019 Preview of Selected Works

ART BASEL 2019 PREVIEW OF SELECTED WORKS GALERIE THOMAS SCHULTE HALL 2.1, BOOTH M16 • Rebecca Horn, Between The Knives The Emptiness, 2014 (detail) Artists on view Also represented Contact Angela de la Cruz Dieter Appelt Galerie Thomas Schulte Hamish Fulton Alice Aycock Charlottenstraße 24 Rebecca Horn Richard Deacon 10117 Berlin Idris Khan David Hartt fon: +49 (0)30 2060 8990 Jonathan Lasker Julian Irlinger fax: +49 (0)30 2060 89910 Michael Müller Alfredo Jaar [email protected] Albrecht Schnider Paco Knöller www.galeriethomasschulte.de Pat Steir Allan McCollum Juan Uslé Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle Thomas Schulte Stephen Willats Robert Mapplethorpe PA Julia Ben Abdallah Fabian Marcaccio [email protected] Gordon Matta-Clark João Penalva Gonzalo Alarcón David Reed +49 (173) 66 46 623 Leunora Salihu [email protected] Iris Schomaker Katharina Sieverding Eike Dürrfeld Jonas Weichsel +49 (172) 30 89 074 Robert Wilson [email protected] Luigi Nerone +49 (172) 30 89 076 [email protected] Juliane Pönisch +49 (151) 22 22 02 70 [email protected] Galerie Thomas Schulte is very pleased to present at this year’s Art Basel recent works by Rebecca Horn, whose exhibition Body Fantasies will be on view at Basel’s Museum Tinguely during the time of the fair (until 22 September). Our booth will also feature works by Angela de la Cruz, Hamish Fulton, Idris Khan, Jonathan Lasker, Michael Müller, Albrecht Schnider, Pat Steir, Juan Uslé and Stephen Willats. This brochure represents a selection of the works at our booth. For further information and to learn more about works which are not shown here, please do not hesitate to contact us. -

Abstraction: on Ambiguity and Semiosis in Abstract Painting

Abstraction: On Ambiguity and Semiosis in Abstract Painting Joseph Daws Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Visual Arts Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2013 2 Abstract This research project examines the paradoxical capacity of abstract painting to apparently ‘resist’ clear and literal communication and yet still generate aesthetic and critical meaning. My creative intention has been to employ experimental and provisional painting strategies to explore the threshold of the readable and the recognisable for a contemporary abstract painting practice. Within the exegetical component I have employed Damisch’s theory of /cloud/, as well as the theories expressed in Gilles Deleuze’s Logic of Sensation, Jan Verwoert ‘s writings on latency, and abstraction in selected artists’ practices. I have done this to examine abstract painting’s semiotic processes and the qualities that can seemingly escape structural analysis. By emphasizing the latent, transitional and dynamic potential of abstraction it is my aim to present a poetically-charged comprehension that problematize viewers’ experiences of temporality and cognition. In so doing I wish to renew the creative possibilities of abstract painting. 3 Keywords abstract, ambiguity, /cloud/, contemporary, Damisch, Deleuze, latency, transition, painting, passage, threshold, semiosis, Verwoert 4 Signed Statement of Originality The work contained in this thesis has not been previously submitted to meet requirements for an award at this or any other higher institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text. Signature: Date: 6th of February 2014 5 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my Principal Supervisor Dr Daniel Mafe and Associate Supervisor Dr Mark Pennings and acknowledge their contributions to this research project. -

Miguel Abreu Gallery

miguel abreu gallery FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Exhibition: Pieter Schoolwerth Model as Painting Dates: May 21 – June 30, 2017 Reception: Sunday, May 21, 6 – 8PM Miguel Abreu Gallery is pleased to announce the opening on Sunday, May 21st, of Model as Painting, Pieter Schoolwerth’s sixth solo exhibition at the gallery. The show will be held at both our 88 Eldridge and 36 Orchard Street locations. One of the clear characteristics of our digital age is that in it all things, bodies even are generally suspended from their material substance. This increasingly spectral state of affairs is the effect of mostly invisible forces of abstraction that can be associated with the digitization of more and more aspects of experience. We as living beings are now confronting a structural split between the substance of things and their virtual double. To speak concretely, one can point to everyday phenomena such as coffee without caffeine, or food without fat, for example, but also to money without currency, love without bodies, and soon following, to painting without paint, and art without art… In Model as Painting, Pieter Schoolwerth attempts to reverse the above described techno-cultural trend by producing a series of ‘in the last instance’ paintings, in which the stuff of paint itself reappears at the very end only of a complex, multi-media effort to produce a figurative picture. As such, paint here is not immediately used to build up an image from the ground up, if you will, one brush stroke at a time, but rather it arrives only to mark the painting after it has been fully formed and output onto canvas. -

Art Basel MIAMI BEACH 2018 Preview of Selected Works

ART BASEL MIAMI BEACH 2018 PREVIEW OF SELECTED WORKS GALERIE THOmaS SCHULTE BOOTH C18 • Alice Aycock, Alien Twister, 2018 (detail, rendering) Artists on view Also represented Contact Alice Aycock Dieter Appelt Galerie Thomas Schulte Angela de la Cruz Richard Deacon Charlottenstraße 24 Alfredo Jaar David Hartt 10117 Berlin Idris Khan Julian Irlinger fon: +49 (0)30 2060 8990 Jonathan Lasker Paco Knöller fax: +49 (0)30 2060 89910 Robert Mapplethorpe Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle [email protected] Allan McCollum Gordon Matta-Clark www.galeriethomasschulte.de Michael Müller Fabian Marcaccio Pat Steir João Penalva Gonzalo Alarcón Jonas Weichsel David Reed +49 (173) 66 46 623 Leunora Salihu [email protected] Iris Schomaker Katharina Sieverding Eike Dürrfeld Juan Uslé +49 (172) 30 89 074 Stephen Willats [email protected] Robert Wilson Luigi Nerone +49 (172) 30 89 076 [email protected] Thomas Schulte PA Julia Ben Abdallah [email protected] As the most prominent artistic positions of this year’s booth at Art Basel Miami Beach, Galerie Thomas Schulte is pleased to present major works by two of America’s most renowned women artists of the past decades, Alice Aycock and Pat Steir, whose outstanding work is currently being reassessed and revalued by museums and institutions world-wide. The main section of the booth will feature an installation of works by Allan McCollum, Jonathan Lasker, and Alfredo Jaar—three of the defining positions of the gallery’s program—alongside works by younger, upcoming European artists from the program including Angela de la Cruz, Idris Khan, Michael Müller, and Jonas Weichsel. Finally, a highlight of this year’s presentation will be a selection of works by American star photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. -

Jonathan Lasker

GALERIE THADDAEUS ROPAC JONATHAN LASKER RECENT PAINTINGS SALZBURG VILLA KAST 21 Saturday - 21 Tuesday "My painting is both spontaneous and highly conscious. There is a split between the conscious and the unconscious. My painting is very flexible, it goes back and forth between the two." Jonathan Lasker We are delighted to announce our fourth exhibition with new works by the American painter Jonathan Lasker. Jonathan Lasker was born in Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1948; he lives and works in New York City. Since the early 1980s, his work has been exhibited in many one-man shows, including the ICA Philadelphia, Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam and Kunstverein St. Gallen. He participated in the 1992 documenta IX in Kassel. After a highly acclaimed travelling exhibition in 2000 (St. Louis, Toronto, Waltham and Birmingham) with a selection of pictures from the 1990s, Jonathan Lasker's presence in the art world culminated in a major retrospective, Jonathan Lasker 1977-2003, in the North Rhine-Westphalia Art Collection in Düsseldorf and the famous Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid. From the late 1970s, Lasker's formal language developed from a reaction to an increasingly conceptual trend in art, against which he wished to explore the possibilities of painting, aiming at a system of painting "which could legitimise itself" (Jonathan Lasker). The formal language of Lasker's pictures is abstract. The spectrum ranges from cipher-like markings to forms which might be categorised more as emblematic. They are always, however, self-referential, thus concerning painting itself, which Lasker takes as his actual theme by conjugating its multifarious linguistic and syntactic possibilities. -

Peter Halley

PETER HALLEY BIOGRAPHY 1953 Born in New York City 1971 Graduates from Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts 1975 Studies at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 1976 Moves to New Orleans 1978 Studies at University of New Orleans 1980 Moves to New York City 1981 Publishes ‘Beat, Minimalism, New Wave, and Robert Smithson’, the first of six essays to appear in Arts Magazine, New York 1985 Solo exhibition at International with Monument, New York 1989 Solo exhibition at the Museum Haus Esters, Krefeld, Germany 1991 Retrospective at CAPC Musée d’art contemporain, Bordeaux. Exhibition tours to FAE Musée d’art contemporain, Pully/Lausanne, the Reina Sofía, Madrid, and the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam 1995 First large-scale installation at the Dallas Museum of Art 1996 Founds index, a bi-monthly magazine covering independent culture. Publishes index until 2005 1996-99 Serves as Adjunct Professor, U.C.L.A., School of Art and Architecture, Los Angeles 1997 New Concepts of Printmaking 1: Peter Halley at the Museum of Modern Art, New York 1999 Appointed Senior Lecturer in Painting, Yale University, School of Art, New Haven, Connecticut 2000 Begins teaching as Adjunct Professor, Columbia University, New York City 2001 Receives the annual Frank Jewett Mather Award for published art criticism from the College Art Association 2002 Appointed Director of Graduate Studies in Painting and Printmaking at the Yale University School of Art, until 2011 Permanent installation of wall-size digital prints at the public library in Usera, Spain, commissioned -

Peter Halley Paintings of the 1980S the Catalogue Raisonné Cara Jordan Table of Contents

Peter Halley Paintings of the 1980s The Catalogue Raisonné Cara Jordan Table of Contents Introduction 4 Cara Jordan Facts Are Useless in Emergencies 6 Paul Pieroni Guide to the Catalogue Raisonné 11 Catalogue Raisonné Peter Halley in front of his first New York studio at 128 East 7th Street, 1985 1980 13 1981 23 1982 37 1983 47 1984 59 1985 67 1986 93 1987 125 1988 147 1989 167 Appendix Biography 187 Solo Exhibitions 1980–1989 188 Group Exhibitions 1980–1989 190 Introduction Cara Jordan The publication of this catalogue raisonné of Peter Halley’s through a diagrammatic representation of space. His paintings French Post-Structuralist theorists such as Michel Foucault and and SCHAUWERK Sindelfingen; and the numerous galleries paintings from the 1980s offers a significant opportunity to reflect transformed the paradigmatic square of abstract art into refer- Jean Baudrillard to the North American art world—emphatically and art dealers who have supported Halley’s work throughout on the early works and career of one of the most well-known en tial icons that he labeled “prisons” and “cells,” and linked them refuted the traditional humanist and spiritual aspirations of art.1 the years, including Thomas Ammann Fine Art AG, Galerie artists of the Neo-Conceptualist generation. It was during these by means of straight lines he called “conduits.” Through this His writings described the shifting relationship between the Bruno Bischofberger, Galerie Andrea Caratsch, Greene Naftali years that Halley developed the hallmark iconography and formal simple icono graphy, which remains the basis of Halley’s visual individual and larger social structures triggered by technology Gallery, Margo Leavin Gallery, Galería Javier López & Fer language of his paintings, which connected the tradition of language, he created a compartmentalized space connected by and the digital revolution, leading critic Paul Taylor to name Francés, Maruani Mercier Gallery, and Sonnabend Gallery. -

Research on the Characteristics of Abstract Painting

2020 8th International Education, Economics, Social Science, Arts, Sports and Management Engineering Conference (IEESASM 2020) Research on the Characteristics of Abstract Painting Luomin Pan Graduate School of Namseoul University, Cheonan 31020, Korea [email protected] Keywords: Abstract painting, Light and color, Music, Space Abstract: This article analyzes the painting works of the representative artists of the AbstractSchool and the New AbstractSchool, and conducts an Expandability research on the characteristics of Abstractpainting. The first part, “The Confusion of Light and Color”, is to understand the color of “multi-personality” from a new perspective. Color does not have immutable meanings forever. The signs of color depend on the artist's creative intentions. The second part, “The Musical Sense of AbstractPainting”, analyzes the musicality of painting through points, lines and surfaces. The musicality of painting allows us to think about more possibilities in the parallel world of painting and music. The third part “Reconstruction of Space” analyzes the multi-dimensional space of Abstractpainting, the indifferent two-dimensional space between two-dimensional and three-dimensional, the multi-dimensional space in two-dimensional and the new space. The study of painting space is an important proposition of Abstractpainting. The author hopes to explore the characteristics of Abstractpainting to inspire us how to deal with old things and old topics, to make new thinking, and to provide more templates for artistic creation and thinking on easel. 1. Introduction The light and color in painting is a basic concept. Only when there is light, there is color. The color we are discussing here refers to the color of painting, and light is the premise of its appearance. -

Jonathan Lasker's Dramatis Personae

“Jonathan Lasker’s Dramatis Personae.” In Jonathan Lasker: Paintings, Drawings, Studies. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in co-production with K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, 2003; pp. 110-119. Text © Robert Hobbs Robert Hobbs Jonathan Laskers Dramatis Personae After attending Queens College for less than a year in the artists as Allan Kaprow, Nam June Paik., John Baldessari, late 1960s, Jonathan Lasker quit school to play bass guitar Michael Asher, and Douglas Huebler. The school was also and blues harmonica with rock bands. At age twenty-two heir to a relatively recent California Neo-Dadaist tradi this quest took him to Europe for four years, first to Eng tion that curator Walter Hopps inaugurated in 1963 when 110 land, where he worked with a couple of short-lived he staged a full-scale, highly celebrated Marcel Duchamp groups, and then to Germany, where he was employed retrospective at the Pasadena Museum of Art. The pri intermittently as a longshoreman and a house painter. He mary conduits between this particular exhibition and the then came to grips with what he calls his "lack of success Institute's pedagogy were the Californians Baldessari and as a musician" and decided to maximize his strengths, Asher. Lasker called the latter "the Grand Inquisitor which included a long-term fascination with art, coupled against painting," since he assumed personal responsibi with "excellent eye-hand coordination," by becoming a lity for eradicating the last vestiges of modernist senti painter. 1 He returned to New York, where he became an ments in students' works. -

Curating Now: Imaginative Practice/Public Responsibility Morning Session: Sunday, October 15, 2000 Edited by Paula Marincola

QUESTIONS OF PRACTICE Curating Now: Imaginative Practice/Public Responsibility Morning Session: Sunday, October 15, 2000 Edited by Paula Marincola THE PEW CENTER FOR ARTS & HERITAGE / PCAH.US / @PEWCENTER_ARTS PHILADELPHIA EXHIBITIONS INITIATIVE CURATING NOW MORNING SESSION SUNDAY, OCTOBER 15, 2000 Institute of Contemporary Art 124 RESPONSE Dave Hickey > Writer and art critic, Professor of Art Criticism and Theory, University of Nevada, Las Vegas It’s very nice to be here in Philadelphia. I was trying to think of the turn on W.C. Fields’s epitaph—that, probably, on the whole, I’d rather be dead. But that’s not it, since I really appreciate this opportunity.Although I have to doubt the wisdom of The Pew Charitable Trusts in bringing a person like myself here to address a group of people who represent more capital leverage, more institu- tional authority, and more political power than the entire continent of Latin America. Here’s what Pew has done:They have asked a private citizen, who lives in a small apartment in a small city in the middle of the desert, who teaches at a small university where they don’t like him, who writes periodical art journalism, the weakest kind of writing you can do, to respond to your discussions of curat- ing.And so I shall, and you may take everything I say with that very large grain of salt. I realize, as I look around, that I am probably the senior person in this room, so the future is almost certainly yours. I do, however, have thirty-five years of experience in various ghettos of the art world.