Stroke of Genius: Gesture and Brushstroke in Postmodernist Painting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sean Scully: Inside Outside Media Release

Sean Scully: Inside Outside Media Release Longside Gallery and Open Air 29 September 2018–6 January 2019 “I have spent my life making the melancholic into something irresistible. Because the world has changed around me and become more regretful, my paintings have become more true.” Sean Scully Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP) presents Sean Scully: Inside Outside, the largest-ever presentation of sculptures and first exhibition of sculpture and painting in the UK by the Irish-born artist. Exploring concepts of landscape and abstraction with human experience, the exhibition unites sculpture with important recent paintings on aluminium, together with works on paper. Drawing out ideas pertinent to the singularity of YSP and its landscape, this is a poetic, robust experience that embraces the Park’s topography and Scully’s exceptional vigour, as well as his belief that in life and art there is perpetual discovery. The exhibition presents an artist at the height of his powers. Aged 72, it is evident that there is no curtailment of Scully’s energy, drive and vision. Keenly aware of the labour that dominated the lives of his mining family, Scully’s practice is one of great rigour and toil, his output prodigious. For YSP he has made new paintings and sculpture – resolutely contemporary works that integrate an inclination towards geometry with the romantic sincerity of landscape painting in the historical tradition. Born in Dublin in 1945, raised in London, and now resident in New York, London and Germany, Scully is considered to be one of the most important abstract painters working today. Drawing on European traditions but with the distinct character and scale prevalent Shadow Stack, 2018 and Landline Inwards, 2015 in the USA, Scully is credited with reinvigorating abstract painting. -

Path to Equilibrium Foozhan Kashkooli Winthrop University

Winthrop University Digital Commons @ Winthrop University Graduate Theses The Graduate School 5-2015 Path to Equilibrium Foozhan Kashkooli Winthrop University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation Kashkooli, Foozhan, "Path to Equilibrium" (2015). Graduate Theses. 3. https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses/3 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PATH TO EQUILIBRIUM A Thesis Statement Presented to the Faculty of the College of Visual and Performing Arts In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Degree Of Master of Fine Arts In the Department of Fine Arts Winthrop University May 2015 By Foozhan Kashkooli Abstract This statement outlines the theoretical, historical, and conceptual influences that shape my Master of Fine Arts thesis at Winthrop University. It further describes and analyzes the series of paintings that compose my thesis Equilibrium, each one a reflection of my aesthetic experience as I evolved as an artist. As I will illustrate, the aesthetic experiences reflected in my work are intertwined with the artist or movement that inspired me at the time. The series consists of seven large-scale, abstract paintings, where I explore balancing form, shape, and color. In this thesis statement, I am asserting my progression as an evolving artist and elucidating my investigation of painting as a unique medium with its own complexity of composition and arrangements of shape, form, and color. -

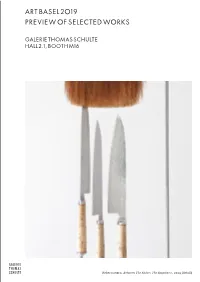

Art Basel 2019 Preview of Selected Works

ART BASEL 2019 PREVIEW OF SELECTED WORKS GALERIE THOMAS SCHULTE HALL 2.1, BOOTH M16 • Rebecca Horn, Between The Knives The Emptiness, 2014 (detail) Artists on view Also represented Contact Angela de la Cruz Dieter Appelt Galerie Thomas Schulte Hamish Fulton Alice Aycock Charlottenstraße 24 Rebecca Horn Richard Deacon 10117 Berlin Idris Khan David Hartt fon: +49 (0)30 2060 8990 Jonathan Lasker Julian Irlinger fax: +49 (0)30 2060 89910 Michael Müller Alfredo Jaar [email protected] Albrecht Schnider Paco Knöller www.galeriethomasschulte.de Pat Steir Allan McCollum Juan Uslé Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle Thomas Schulte Stephen Willats Robert Mapplethorpe PA Julia Ben Abdallah Fabian Marcaccio [email protected] Gordon Matta-Clark João Penalva Gonzalo Alarcón David Reed +49 (173) 66 46 623 Leunora Salihu [email protected] Iris Schomaker Katharina Sieverding Eike Dürrfeld Jonas Weichsel +49 (172) 30 89 074 Robert Wilson [email protected] Luigi Nerone +49 (172) 30 89 076 [email protected] Juliane Pönisch +49 (151) 22 22 02 70 [email protected] Galerie Thomas Schulte is very pleased to present at this year’s Art Basel recent works by Rebecca Horn, whose exhibition Body Fantasies will be on view at Basel’s Museum Tinguely during the time of the fair (until 22 September). Our booth will also feature works by Angela de la Cruz, Hamish Fulton, Idris Khan, Jonathan Lasker, Michael Müller, Albrecht Schnider, Pat Steir, Juan Uslé and Stephen Willats. This brochure represents a selection of the works at our booth. For further information and to learn more about works which are not shown here, please do not hesitate to contact us. -

Abstraction: on Ambiguity and Semiosis in Abstract Painting

Abstraction: On Ambiguity and Semiosis in Abstract Painting Joseph Daws Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Visual Arts Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2013 2 Abstract This research project examines the paradoxical capacity of abstract painting to apparently ‘resist’ clear and literal communication and yet still generate aesthetic and critical meaning. My creative intention has been to employ experimental and provisional painting strategies to explore the threshold of the readable and the recognisable for a contemporary abstract painting practice. Within the exegetical component I have employed Damisch’s theory of /cloud/, as well as the theories expressed in Gilles Deleuze’s Logic of Sensation, Jan Verwoert ‘s writings on latency, and abstraction in selected artists’ practices. I have done this to examine abstract painting’s semiotic processes and the qualities that can seemingly escape structural analysis. By emphasizing the latent, transitional and dynamic potential of abstraction it is my aim to present a poetically-charged comprehension that problematize viewers’ experiences of temporality and cognition. In so doing I wish to renew the creative possibilities of abstract painting. 3 Keywords abstract, ambiguity, /cloud/, contemporary, Damisch, Deleuze, latency, transition, painting, passage, threshold, semiosis, Verwoert 4 Signed Statement of Originality The work contained in this thesis has not been previously submitted to meet requirements for an award at this or any other higher institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text. Signature: Date: 6th of February 2014 5 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my Principal Supervisor Dr Daniel Mafe and Associate Supervisor Dr Mark Pennings and acknowledge their contributions to this research project. -

Miguel Abreu Gallery

miguel abreu gallery FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Exhibition: Pieter Schoolwerth Model as Painting Dates: May 21 – June 30, 2017 Reception: Sunday, May 21, 6 – 8PM Miguel Abreu Gallery is pleased to announce the opening on Sunday, May 21st, of Model as Painting, Pieter Schoolwerth’s sixth solo exhibition at the gallery. The show will be held at both our 88 Eldridge and 36 Orchard Street locations. One of the clear characteristics of our digital age is that in it all things, bodies even are generally suspended from their material substance. This increasingly spectral state of affairs is the effect of mostly invisible forces of abstraction that can be associated with the digitization of more and more aspects of experience. We as living beings are now confronting a structural split between the substance of things and their virtual double. To speak concretely, one can point to everyday phenomena such as coffee without caffeine, or food without fat, for example, but also to money without currency, love without bodies, and soon following, to painting without paint, and art without art… In Model as Painting, Pieter Schoolwerth attempts to reverse the above described techno-cultural trend by producing a series of ‘in the last instance’ paintings, in which the stuff of paint itself reappears at the very end only of a complex, multi-media effort to produce a figurative picture. As such, paint here is not immediately used to build up an image from the ground up, if you will, one brush stroke at a time, but rather it arrives only to mark the painting after it has been fully formed and output onto canvas. -

Art Basel MIAMI BEACH 2018 Preview of Selected Works

ART BASEL MIAMI BEACH 2018 PREVIEW OF SELECTED WORKS GALERIE THOmaS SCHULTE BOOTH C18 • Alice Aycock, Alien Twister, 2018 (detail, rendering) Artists on view Also represented Contact Alice Aycock Dieter Appelt Galerie Thomas Schulte Angela de la Cruz Richard Deacon Charlottenstraße 24 Alfredo Jaar David Hartt 10117 Berlin Idris Khan Julian Irlinger fon: +49 (0)30 2060 8990 Jonathan Lasker Paco Knöller fax: +49 (0)30 2060 89910 Robert Mapplethorpe Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle [email protected] Allan McCollum Gordon Matta-Clark www.galeriethomasschulte.de Michael Müller Fabian Marcaccio Pat Steir João Penalva Gonzalo Alarcón Jonas Weichsel David Reed +49 (173) 66 46 623 Leunora Salihu [email protected] Iris Schomaker Katharina Sieverding Eike Dürrfeld Juan Uslé +49 (172) 30 89 074 Stephen Willats [email protected] Robert Wilson Luigi Nerone +49 (172) 30 89 076 [email protected] Thomas Schulte PA Julia Ben Abdallah [email protected] As the most prominent artistic positions of this year’s booth at Art Basel Miami Beach, Galerie Thomas Schulte is pleased to present major works by two of America’s most renowned women artists of the past decades, Alice Aycock and Pat Steir, whose outstanding work is currently being reassessed and revalued by museums and institutions world-wide. The main section of the booth will feature an installation of works by Allan McCollum, Jonathan Lasker, and Alfredo Jaar—three of the defining positions of the gallery’s program—alongside works by younger, upcoming European artists from the program including Angela de la Cruz, Idris Khan, Michael Müller, and Jonas Weichsel. Finally, a highlight of this year’s presentation will be a selection of works by American star photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. -

Jonathan Lasker

GALERIE THADDAEUS ROPAC JONATHAN LASKER RECENT PAINTINGS SALZBURG VILLA KAST 21 Saturday - 21 Tuesday "My painting is both spontaneous and highly conscious. There is a split between the conscious and the unconscious. My painting is very flexible, it goes back and forth between the two." Jonathan Lasker We are delighted to announce our fourth exhibition with new works by the American painter Jonathan Lasker. Jonathan Lasker was born in Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1948; he lives and works in New York City. Since the early 1980s, his work has been exhibited in many one-man shows, including the ICA Philadelphia, Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam and Kunstverein St. Gallen. He participated in the 1992 documenta IX in Kassel. After a highly acclaimed travelling exhibition in 2000 (St. Louis, Toronto, Waltham and Birmingham) with a selection of pictures from the 1990s, Jonathan Lasker's presence in the art world culminated in a major retrospective, Jonathan Lasker 1977-2003, in the North Rhine-Westphalia Art Collection in Düsseldorf and the famous Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid. From the late 1970s, Lasker's formal language developed from a reaction to an increasingly conceptual trend in art, against which he wished to explore the possibilities of painting, aiming at a system of painting "which could legitimise itself" (Jonathan Lasker). The formal language of Lasker's pictures is abstract. The spectrum ranges from cipher-like markings to forms which might be categorised more as emblematic. They are always, however, self-referential, thus concerning painting itself, which Lasker takes as his actual theme by conjugating its multifarious linguistic and syntactic possibilities. -

New Art Thing That Follows, and That Comes from an Interest in Irish Music – I 1

Interview Dr Mark Merrony, Director of the Musée d’Art Classique de Mougins, interviews the internationally renowned abstract artist Sean Scully in his Barcelona studio How old were you when you first started to paint or draw? I was about six. While I was at a convent school I was very involved with things like Nativity plays and I used to make the scenery. I was always the school artist. When you were at art school did you only paint abstract pictures? No. I started making very realistic drawings and I drew obsessively for the first couple of years. I pro- duced a lot of beautiful drawings of friends, plants, animals, landscapes. I am showing them in Ireland and in Germany; there is going to be an exhibition that explains this story. I am one of the few artists knock- ing around now that made the tran- 1 sition from realism to abstraction. What was it that steered you towards abstraction? I would say that the drive to abstraction is fundamental to every- Ancient order – new art thing that follows, and that comes from an interest in Irish music – I 1. Sean Scully in 1992, of gravitas and there is a kind of cardboard boxes, and I always was mean, that’s in my soul, and the standing in front of Doric order about them.’ That’s very fascinated by this idea of stack- idea of rhythm, the sense of rhythm, the Doric columns of when I first got the idea of making ing, and just being able to go up by that’s deep within me. -

Sean Scully, 1945 —

Sean Scully, 1945 — Sean Scully (b. 1945, Dublin, Ireland) is an American-Irish artist who is internationally recognised for his distinctive abstract compositions that interrogate the properties of light, colour and form. Scully studied painting at Croydon College of Art, London and Newcastle University, UK, where he began to work in abstraction. During a trip to Morocco in 1969, Scully was strongly influenced by the local textiles and rich colours of the region, which he translated into the broad horizontal stripes and deep earth tones that characterise his mature style. Scully’s travels throughout Morocco and Mexico would also prompt his decision to move from Minimalism to a more emotional and humanistic form of abstraction. Following fellowships in 1972 and 1975 at Harvard University, Scully’s paintings became increasingly monumental and sculptural, consisting of interconnected three-dimensional panels that anticipated his later sculpture practice. In 1984 he began to develop the Wall of Light series, replacing the precise stripes of his early paintings with solid blocks of colour, built with increasingly loose and feathered brushstrokes into vertical and horizontal ‘bricks’ that suggest a wall of stone. Subtle differences in colour in the paintings indicate the location in which they were created, the changing seasons and the artist’s own emotions. This series formed the subject of a major touring exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York in 2007. In 1984 Scully achieved international breakthrough through his inclusion in the major group exhibition An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. -

Jonathan Lasker's Dramatis Personae

“Jonathan Lasker’s Dramatis Personae.” In Jonathan Lasker: Paintings, Drawings, Studies. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in co-production with K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, 2003; pp. 110-119. Text © Robert Hobbs Robert Hobbs Jonathan Laskers Dramatis Personae After attending Queens College for less than a year in the artists as Allan Kaprow, Nam June Paik., John Baldessari, late 1960s, Jonathan Lasker quit school to play bass guitar Michael Asher, and Douglas Huebler. The school was also and blues harmonica with rock bands. At age twenty-two heir to a relatively recent California Neo-Dadaist tradi this quest took him to Europe for four years, first to Eng tion that curator Walter Hopps inaugurated in 1963 when 110 land, where he worked with a couple of short-lived he staged a full-scale, highly celebrated Marcel Duchamp groups, and then to Germany, where he was employed retrospective at the Pasadena Museum of Art. The pri intermittently as a longshoreman and a house painter. He mary conduits between this particular exhibition and the then came to grips with what he calls his "lack of success Institute's pedagogy were the Californians Baldessari and as a musician" and decided to maximize his strengths, Asher. Lasker called the latter "the Grand Inquisitor which included a long-term fascination with art, coupled against painting," since he assumed personal responsibi with "excellent eye-hand coordination," by becoming a lity for eradicating the last vestiges of modernist senti painter. 1 He returned to New York, where he became an ments in students' works. -

WADSWORTH ATHENEUM MUSEUM of ART Annual Report 2019 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 WADSWORTH ATHENEUM MUSEUM of ART

WADSWORTH ATHENEUM MUSEUM OF ART Annual Report 2019 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 WADSWORTH ATHENEUM MUSEUM OF ART Contents 3 From the President 5 Report: the Year in Review 8 175 Years of Serving the Community 12 Making Museums Matter 18 Understanding Artemisia 24 Exhibitions & Acquisitions 40 Program Highlights 54 People, Donors & Gifts 80 Financials Cover: Nicolaes van Verendael, A Still Life, 1682. Oil on copper. The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 2019.8.1 From the President This annual report, capturing the activities of the museum between July 2018 and June 2019, is filled with the variety and quality of experiences and impacts generated by the committed staff, dedicated volunteers of our support organizations, and devoted board of trustees of our institution, on the 175th anniversary of the beginning of the museum’s service to the public. Though the Wadsworth was founded in 1842, it was not until the late summer of 1844 that we opened our doors and truly took hold as a beacon for the visual arts, located at the heart of Hartford, instigating conversations about art which resonate with people—then as now—from all over. We are informed by our history but we are keeping our sights on the future. Our program horizon is robust. None of it would be possible without the steadfast commitment and support from so many of you. My thanks for all you do to ensure the healthy future of this great museum. William R. Peelle, Jr. President, Board of Trustees Left: Sol LeWitt, Black and White Horizontal Lines on Color, 2005. -

Annual Report

July 1, 2007–June 30, 2008 AnnuAl RepoRt 1 Contents 3 Board of Trustees 4 Trustee Committees 7 Message from the Director 12 Message from the Co-Chairmen 14 Message from the President 16 Renovation and Expansion 24 Collections 55 Exhibitions 60 Performing Arts, Music, and Film 65 Community Support 116 Education and Public Programs Cover: Banners get right to the point. After more than 131 Staff List three years, visitors can 137 Financial Report once again enjoy part of the permanent collection. 138 Treasurer Right: Tibetan Man’s Robe, Chuba; 17th century; China, Qing dynasty; satin weave T with supplementary weft Prober patterning; silk, gilt-metal . J en thread, and peacock- V E feathered thread; 184 x : ST O T 129 cm; Norman O. Stone O PH and Ella A. Stone Memorial er V O Fund 2007.216. C 2 Board of Trustees Officers Standing Trustees Stephen E. Myers Trustees Emeriti Honorary Trustees Alfred M. Rankin Jr. Virginia N. Barbato Frederick R. Nance Peter B. Lewis Joyce G. Ames President James T. Bartlett Anne Hollis Perkins William R. Robertson Mrs. Noah L. Butkin+ James T. Bartlett James S. Berkman Alfred M. Rankin Jr. Elliott L. Schlang Mrs. Ellen Wade Chinn+ Chair Charles P. Bolton James A. Ratner Michael Sherwin Helen Collis Michael J. Horvitz Chair Sarah S. Cutler Donna S. Reid Eugene Stevens Mrs. John Flower Richard Fearon Dr. Eugene T. W. Sanders Mrs. Robert I. Gale Jr. Sarah S. Cutler Life Trustees Vice President Helen Forbes-Fields David M. Schneider Robert D. Gries Elisabeth H. Alexander Ellen Stirn Mavec Robert W.