In the Great War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bushytelegraph PARK CENTREPIECE COMES HOME

ISSUE JANUARY 2010 8 BushyTelegraph PARK CENTREPIECE COMES HOME The final major part of Bushy Park’s renaissance was completed at the end of last year with the New discovery restoration of the Diana Fountain. During the restoration, the project team uncovered a stone The gilded statue arrived home in November, after four at the base of the statue carved with a crown and the date months of renovation in south London. The scaffolding AR 1712. This would have been added when the statue and around the fountain’s stonework was removed in the fountain were installed in the basin in the middle of Chestnut following week, revealing the magnificent centrepiece Avenue as part of Sir Christopher Wren’s plan to create a of the park. grand route through Bushy Park to Hampton Court gardens. This was the first time in 300 years that the statute The fountain originally stood in the garden of had been moved and the first chance to get an Somerset House and was designed in the 1630s accurate idea of her size: 2.38m tall and 924kg in by the French sculptor, Hubert Le Sueur, for weight. During the restoration, the statue was King Charles l. In 1656, it was moved to Hampton cleaned, coated in four layers of paint, each Court and then just over 60 years later it one slightly more yellow than the last, and moved again to Bushy Park. then finally gilded. Final Bushy Telegraph Bronze and This is the final Bushy Telegraph. We hope you enjoy it as much as the previous issues, which stonework have covered the Bushy Park Restoration The fountain’s bronzes – four boys, Project since 2005. -

10 Downing Street

10 DOWNING STREET 8th June, 1981 "ANYONE FOR DENIS?" - SUNDAY, 12TH JULY 1981 AT 7.30 P.M. Thank you so much for your letter of 29th May. I reply to your numbered questions as follows:- Five (the Prime Minister, Mr. Denis Thatcher, Mr. Mark Thatcher, Jane and me.) In addition, there will be two (or possibly three) Special Branch Officers. None of these will be paying for tickets. No. but of course any Cabinet Minister is at liberty . to buy a ticket that evening, like anyone else, if he wishes to do so. I would not feel inclined to include any Opposition Member on the mailing list. No. The Prime Minister wi.11 be glad to have a photocall at 10 Downing Street at 6.45 p.m., when she would hand over cheques to representatives of the N.S.P.C.C. and of Stoke Mandeville. Who will these representatives be, please? The Prime Minister does not agree that Angela Thorne should wear the same outfit. The Prime Minister will be pleased to give a small reception for say sixty people. Would you please submit a list of names? I do not understand in what role it is suggested that Mr. Paul Raymond should attend the reception after the performance. By all means let us have a word about this on the telephone. Ian Gow Michael Dobbs, Esq, 10 DOWNING STREET Q4 Is, i ki t « , s 71 i 1-F Al 4-) 41e. ASO C a lie 0 A-A SAATCHI & SAATCHI GARLAND-CONIPTON LTD , \\ r MD/sap 29th May 1981 I. -

London National Park City Week 2018

London National Park City Week 2018 Saturday 21 July – Sunday 29 July www.london.gov.uk/national-park-city-week Share your experiences using #NationalParkCity SATURDAY JULY 21 All day events InspiralLondon DayNight Trail Relay, 12 am – 12am Theme: Arts in Parks Meet at Kings Cross Square - Spindle Sculpture by Henry Moore - Start of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail, N1C 4DE (at midnight or join us along the route) Come and experience London as a National Park City day and night at this relay walk of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail. Join a team of artists and inspirallers as they walk non-stop for 48 hours to cover the first six parts of this 36- section walk. There are designated points where you can pick up the trail, with walks from one mile to eight miles plus. Visit InspiralLondon to find out more. The Crofton Park Railway Garden Sensory-Learning Themed Garden, 10am- 5:30pm Theme: Look & learn Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, SE4 1AZ The railway garden opens its doors to showcase its plans for creating a 'sensory-learning' themed garden. Drop in at any time on the day to explore the garden, the landscaping plans, the various stalls or join one of the workshops. Free event, just turn up. Find out more on Crofton Park Railway Garden Brockley Tree Peaks Trail, 10am - 5:30pm Theme: Day walk & talk Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, London, SE4 1AZ Collect your map and discount voucher before heading off to explore the wider Brockley area along a five-mile circular walk. The route will take you through the valley of the River Ravensbourne at Ladywell Fields and to the peaks of Blythe Hill Fields, Hilly Fields, One Tree Hill for the best views across London! You’ll find loads of great places to enjoy food and drink along the way and independent shops to explore (with some offering ten per cent for visitors on the day with your voucher). -

Buses from Battersea Park

Buses from Battersea Park 452 Kensal Rise Ladbroke Grove Ladbroke Grove Notting Hill Gate High Street Kensington St Charles Square 344 Kensington Gore Marble Arch CITY OF Liverpool Street LADBROKE Royal Albert Hall 137 GROVE N137 LONDON Hyde Park Corner Aldwych Monument Knightsbridge for Covent Garden N44 Whitehall Victoria Street Horse Guards Parade Westminster City Hall Trafalgar Square Route fi nder Sloane Street Pont Street for Charing Cross Southwark Bridge Road Southwark Street 44 Victoria Street Day buses including 24-hour services Westminster Cathedral Sloane Square Victoria Elephant & Castle Bus route Towards Bus stops Lower Sloane Street Buckingham Palace Road Sloane Square Eccleston Bridge Tooting Lambeth Road 44 Victoria Coach Station CHELSEA Imperial War Museum Victoria Lower Sloane Street Royal Hospital Road Ebury Bridge Road Albert Embankment Lambeth Bridge 137 Marble Arch Albert Embankment Chelsea Bridge Road Prince Consort House Lister Hospital Streatham Hill 156 Albert Embankment Vauxhall Cross Vauxhall River Thames 156 Vauxhall Wimbledon Queenstown Road Nine Elms Lane VAUXHALL 24 hour Chelsea Bridge Wandsworth Road 344 service Clapham Junction Nine Elms Lane Liverpool Street CA Q Battersea Power Elm Quay Court R UE R Station (Disused) IA G EN Battersea Park Road E Kensal Rise D ST Cringle Street 452 R I OWN V E Battersea Park Road Wandsworth Road E A Sleaford Street XXX ROAD S T Battersea Gas Works Dogs and Cats Home D A Night buses O H F R T PRINCE O U DRIVE H O WALES A S K V Bus route Towards Bus stops E R E IV A L R Battersea P O D C E E A K G Park T A RIV QUEENST E E I D S R RR S R The yellow tinted area includes every Aldwych A E N44 C T TLOCKI bus stop up to about one-and-a-half F WALE BA miles from Battersea Park. -

CALIFORNIA's NORTH COAST: a Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors

CALIFORNIA'S NORTH COAST: A Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors. A Geographically Arranged Bibliography focused on the Regional Small Presses and Local Authors of the North Coast of California. First Edition, 2010. John Sherlock Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian University of California, Davis. 1 Table of Contents I. NORTH COAST PRESSES. pp. 3 - 90 DEL NORTE COUNTY. CITIES: Crescent City. HUMBOLDT COUNTY. CITIES: Arcata, Bayside, Blue Lake, Carlotta, Cutten, Eureka, Fortuna, Garberville Hoopa, Hydesville, Korbel, McKinleyville, Miranda, Myers Flat., Orick, Petrolia, Redway, Trinidad, Whitethorn. TRINITY COUNTY CITIES: Junction City, Weaverville LAKE COUNTY CITIES: Clearlake, Clearlake Park, Cobb, Kelseyville, Lakeport, Lower Lake, Middleton, Upper Lake, Wilbur Springs MENDOCINO COUNTY CITIES: Albion, Boonville, Calpella, Caspar, Comptche, Covelo, Elk, Fort Bragg, Gualala, Little River, Mendocino, Navarro, Philo, Point Arena, Talmage, Ukiah, Westport, Willits SONOMA COUNTY. CITIES: Bodega Bay, Boyes Hot Springs, Cazadero, Cloverdale, Cotati, Forestville Geyserville, Glen Ellen, Graton, Guerneville, Healdsburg, Kenwood, Korbel, Monte Rio, Penngrove, Petaluma, Rohnert Part, Santa Rosa, Sebastopol, Sonoma Vineburg NAPA COUNTY CITIES: Angwin, Calistoga, Deer Park, Rutherford, St. Helena, Yountville MARIN COUNTY. CITIES: Belvedere, Bolinas, Corte Madera, Fairfax, Greenbrae, Inverness, Kentfield, Larkspur, Marin City, Mill Valley, Novato, Point Reyes, Point Reyes Station, Ross, San Anselmo, San Geronimo, San Quentin, San Rafael, Sausalito, Stinson Beach, Tiburon, Tomales, Woodacre II. NORTH COAST AUTHORS. pp. 91 - 120 -- Alphabetically Arranged 2 I. NORTH COAST PRESSES DEL NORTE COUNTY. CRESCENT CITY. ARTS-IN-CORRECTIONS PROGRAM (Crescent City). The Brief Pelican: Anthology of Prison Writing, 1993. 1992 Pelikanesis: Creative Writing Anthology, 1994. 1994 Virtual Pelican: anthology of writing by inmates from Pelican Bay State Prison. -

The Soccer Diaries

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and University of Nebraska Press Chapters Spring 2014 The oS ccer Diaries Michael J. Agovino Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples Agovino, Michael J., "The ocS cer Diaries" (2014). University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters. 271. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples/271 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Nebraska Press at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. the soccer diaries Buy the Book Buy the Book THE SOCCER DIARIES An American’s Thirty- Year Pursuit of the International Game Michael J. Agovino University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London Buy the Book © 2014 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska Portions of this book originally appeared in Tin House and Howler. Images courtesy of United States Soccer Federation (Team America- Italy game program), the New York Cosmos (Cosmos yearbook), fifa and Roger Huyssen (fifa- unicef World All- Star Game program), Transatlantic Challenge Cup, ticket stubs, press passes (from author). All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Agovino, Michael J. The soccer diaries: an American’s thirty- year pursuit of the international game / Michael J. Agovino. pages cm isbn 978- 0- 8032- 4047- 6 (hardback: alk. paper)— isbn 978- 0- 8032- 5566- 1 (epub)— isbn 978-0-8032-5567-8 (mobi)— isbn 978- 0- 8032- 5565- 4 (pdf) 1. -

No 424, February 2020

The Clapham Society Newsletter Issue 424 February 2020 We meet at Omnibus Theatre, 1 Clapham Common North Side, SW4 0QW. Our guests normally speak for about 45 minutes, followed by around 15 minutes for questions and discussion. The bar is open before and after. Meetings are free and open to non-members, who are strongly urged to make a donation. Please arrive in good time before the start to avoid disappointment. Gems of the London Underground Monday 17 February On 18 November, we were treated to a talk about the London Underground network, Sharing your personal data in the the oldest in the world, by architectural historian Edmund Bird, Heritage Manager of Health and Care System. Dr Jack Transport for London. He has just signed off on a project to record every heritage asset Barker, consultant physician at King’s and item of architectural and historic interest at its 270 stations. With photographs and College Hospital, is also the Chief back stories, he took us on a Tube ride like no other. Clinical Information Officer for the six One of his key tools is the London Underground Station Design Idiom, which boroughs of southeast London. He is groups the stations into 20 subsets, based on their era or architectural genre, and the driving force behind attempting to specifies the authentic historic colour schemes, tile/masonry repairs, etc, to be used improve the effectiveness and efficiency for station refurbishments. Another important tool is the London Underground Station of local health and care through the use of Heritage Register, which is an inventory of everything from signs, clocks, station information technology, and he will tell us benches, ticket offices and tiling to station histories. -

Enhancing the Landscape Gavinjones.Co.Uk Enhancing the Landscape Gavinjones.Co.Uk

Enhancing the Landscape gavinjones.co.uk Enhancing the Landscape gavinjones.co.uk LANDSCAPE ROYAL CONSTRUCTION PARKS & PALACES MILITARY BASES 05 © The Royal Parks 13 15 02 Enhancing the Landscape ABOUT US OTHER SERVICES Gavin Jones Ltd is a national landscape Our focus is on the delivery of an optimum construction and maintenance company. quality service that aims not only to meet, From February 2018, Gavin Jones became but to exceed our client’s expectations. part of the Nurture Landscapes Group. Our fully trained staff offer a professional Tree Works Specialising in landscape construction and and diverse range of land management grounds maintenance across the breadth of skills, using a combination of traditional Plant Displays the UK, Gavin Jones strives for excellence in best-practice horticultural techniques and all aspects of work, with a flexible attitude innovative technology, whilst remaining to client requirements. sensitive to the environment in which Winter Gritting we work. 17 www.gavinjones.co.uk 03 04 Enhancing the Landscape LANDSCAPE CONSTRUCTION Gavin Jones Ltd has established an Whether your preference is for a enviable reputation for premium quality negotiated, partnered design & build, or a service and a flexible attitude to meeting more traditional style contract, Gavin Jones, client requirements. will ensure all aspects of the specification are delivered in a timely and cost effective Our dedicated and experienced staff offer manner, with the aim of not only meeting a professional and diverse range of hard but exceeding stakeholder expectations. and soft landscaping skills, together with an all-encompassing project management capability; from small schemes, to multi-million pound contracts. -

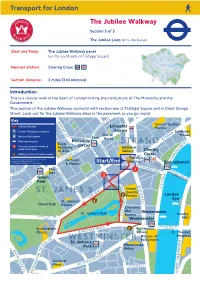

The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5

Transport for London. The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5. The Jubilee Loop (anti-clockwise). Start and finish: The Jubilee Walkway panel (on the south side of Trafalgar Square). Nearest station: Charing Cross . Section distance: 2 miles (3 kilometres). Introduction. This is a circular walk in the heart of London linking the institutions of The Monarchy and the Government. This section of the Jubilee Walkway connects with section one at Trafalgar Square and at Great George Street. Look out for the Jubilee Walkway discs in the pavement as you go round. Directions. This walk starts from Trafalgar Square. Did you know? Trafalgar Square was laid out in 1840 by Sir Charles Barry, architect of the new Houses of Parliament. The square, which is now a 'World Square', is a place for national rejoicing, celebrations and demonstrations. It is dominated by Nelson's Column with the 18-foot statue of Lord Nelson standing on top of the 171-foot column. It was erected in honour of his victory at Trafalgar. With Trafalgar Square behind you and keeping Canada House on the right, cross Cockspur Street and keep right. Go around the corner, passing the Ugandan High Commission to enter The Mall under the large stone Admiralty Arch - go through the right arch. Keep on the right-hand side of the broad avenue that is The Mall. Did you know? Admiralty Arch is the gateway between The Mall, which extends southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. The Mall was laid out as an avenue between 1660-1662 as part of Charles II's scheme for St James's Park. -

Westminster World Heritage Site Management Plan Steering Group

WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN Illustration credits and copyright references for photographs, maps and other illustrations are under negotiation with the following organisations: Dean and Chapter of Westminster Westminster School Parliamentary Estates Directorate Westminster City Council English Heritage Greater London Authority Simmons Aerofilms / Atkins Atkins / PLB / Barry Stow 2 WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN The Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including St. Margaret’s Church World Heritage Site Management Plan Prepared on behalf of the Westminster World Heritage Site Management Plan Steering Group, by a consortium led by Atkins, with Barry Stow, conservation architect, and tourism specialists PLB Consulting Ltd. The full steering group chaired by English Heritage comprises representatives of: ICOMOS UK DCMS The Government Office for London The Dean and Chapter of Westminster The Parliamentary Estates Directorate Transport for London The Greater London Authority Westminster School Westminster City Council The London Borough of Lambeth The Royal Parks Agency The Church Commissioners Visit London 3 4 WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE S I T E M ANAGEMENT PLAN FOREWORD by David Lammy MP, Minister for Culture I am delighted to present this Management Plan for the Palace of Westminster, Westminster Abbey and St Margaret’s Church World Heritage Site. For over a thousand years, Westminster has held a unique architectural, historic and symbolic significance where the history of church, monarchy, state and law are inexorably intertwined. As a group, the iconic buildings that form part of the World Heritage Site represent masterpieces of monumental architecture from medieval times on and which draw on the best of historic construction techniques and traditional craftsmanship. -

1 REGIMENTAL HEADQUARTERS GRENADIER GUARDS Wellington

REGIMENTAL HEADQUARTERS GRENADIER GUARDS Wellington Barracks Birdcage Walk London SW1E 6HQ Telephone: London District Military: 9(4631) } 3280 Civil: 020 7414 } Facsimile: } 3443 Our Reference: 4004 All First Guards Club Members Date: 24th March 2016 FIRST GUARDS’ CLUB INFORMATION - 2016 1. I attach a Regimental Forecast of Events at Annex A. REGIMENTAL REMEMBRANCE SUNDAY – 15 MAY 16 2. Regimental Remembrance Day will be held on Sunday 15th May 2016. HRH The Colonel is unable to attend this year. All those clear of duty from the 1st Battalion and Nijmegen Company will also attend. Please do make the effort to come. 3. The format of the afternoon will be similar to 2015. Members should aim to be in the Guards Chapel by 1445hrs. The service will start at 1500hrs. As usual, officers, unless accompanied by their wives or girlfriends (in which case they should sit with them), should stand on the left hand (northern) side of the Chapel. Sgts Mess members stand on the right side of the Chapel. 4. After the Service, members should form up on their Battalion Marker Boards on the Square as quickly as possible, ready to march to the Guards Memorial in the normal way. 5. There will be a refreshment tent, serving tea, set up at the eastern end of the Square. It will be open prior to the service and after the return from the Guards Memorial for those who wish to slake their thirst and catch up with friends. 6. All members attending should enter and leave by the West Gate in Birdcage Walk. -

1 Start and Finish at St Mary with St Alban Church

A WALK IN TEDDINGTON: 1 Start and finish at St Mary with St Alban Church The old village of Teddington stretched from the river to the railway bridge, which was the site of the village pond through which the railway was built in the early 1860s. The church of St Mary (1) was the old parish church, parts dating from the 16th century. During the incumbency of the Rev Stephen Hales (1709-61) much rebuilding was carried out, the north aisle and the tower being added. The church was too small for the increasing population and in the 19th century more enlargements were carried out until a new church seemed to be the only solution. So the church of St Alban the Martyr (2) was built on the opposite side of the road. The building, which is in the French Gothic style on the scale of a cathedral, was opened in July1896. However, plans were over-ambitious and the money ran out before the west end of the nave was completed. When the new church was opened the old one was closed, but not everybody liked the new church so St Mary’s was repaired and services were held in both churches until 1972. By this time the number of worshippers had diminished and running expenses had risen so much that two churches could no longer be maintained. St Alban’s became redundant and was to be pulled down. Vandals damaged what remained of the internal fittings and part of the copper roof was taken before the destruction was stopped.