1C and Metaphysics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“The Church-Turing “Thesis” As a Special Corollary of Gödel's

“The Church-Turing “Thesis” as a Special Corollary of Gödel’s Completeness Theorem,” in Computability: Turing, Gödel, Church, and Beyond, B. J. Copeland, C. Posy, and O. Shagrir (eds.), MIT Press (Cambridge), 2013, pp. 77-104. Saul A. Kripke This is the published version of the book chapter indicated above, which can be obtained from the publisher at https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/computability. It is reproduced here by permission of the publisher who holds the copyright. © The MIT Press The Church-Turing “ Thesis ” as a Special Corollary of G ö del ’ s 4 Completeness Theorem 1 Saul A. Kripke Traditionally, many writers, following Kleene (1952) , thought of the Church-Turing thesis as unprovable by its nature but having various strong arguments in its favor, including Turing ’ s analysis of human computation. More recently, the beauty, power, and obvious fundamental importance of this analysis — what Turing (1936) calls “ argument I ” — has led some writers to give an almost exclusive emphasis on this argument as the unique justification for the Church-Turing thesis. In this chapter I advocate an alternative justification, essentially presupposed by Turing himself in what he calls “ argument II. ” The idea is that computation is a special form of math- ematical deduction. Assuming the steps of the deduction can be stated in a first- order language, the Church-Turing thesis follows as a special case of G ö del ’ s completeness theorem (first-order algorithm theorem). I propose this idea as an alternative foundation for the Church-Turing thesis, both for human and machine computation. Clearly the relevant assumptions are justified for computations pres- ently known. -

The Universe, Life and Everything…

Our current understanding of our world is nearly 350 years old. Durston It stems from the ideas of Descartes and Newton and has brought us many great things, including modern science and & increases in wealth, health and everyday living standards. Baggerman Furthermore, it is so engrained in our daily lives that we have forgotten it is a paradigm, not fact. However, there are some problems with it: first, there is no satisfactory explanation for why we have consciousness and experience meaning in our The lives. Second, modern-day physics tells us that observations Universe, depend on characteristics of the observer at the large, cosmic Dialogues on and small, subatomic scales. Third, the ongoing humanitarian and environmental crises show us that our world is vastly The interconnected. Our understanding of reality is expanding to Universe, incorporate these issues. In The Universe, Life and Everything... our Changing Dialogues on our Changing Understanding of Reality, some of the scholars at the forefront of this change discuss the direction it is taking and its urgency. Life Understanding Life and and Sarah Durston is Professor of Developmental Disorders of the Brain at the University Medical Centre Utrecht, and was at the Everything of Reality Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study in 2016/2017. Ton Baggerman is an economic psychologist and psychotherapist in Tilburg. Everything ISBN978-94-629-8740-1 AUP.nl 9789462 987401 Sarah Durston and Ton Baggerman The Universe, Life and Everything… The Universe, Life and Everything… Dialogues on our Changing Understanding of Reality Sarah Durston and Ton Baggerman AUP Contact information for authors Sarah Durston: [email protected] Ton Baggerman: [email protected] Cover design: Suzan Beijer grafisch ontwerp, Amersfoort Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. -

A Compositional Analysis for Subset Comparatives∗ Helena APARICIO TERRASA–University of Chicago

A Compositional Analysis for Subset Comparatives∗ Helena APARICIO TERRASA–University of Chicago Abstract. Subset comparatives (Grant 2013) are amount comparatives in which there exists a set membership relation between the target and the standard of comparison. This paper argues that subset comparatives should be treated as regular phrasal comparatives with an added presupposi- tional component. More specifically, subset comparatives presuppose that: a) the standard has the property denoted by the target; and b) the standard has the property denoted by the matrix predi- cate. In the account developed below, the presuppositions of subset comparatives result from the compositional principles independently required to interpret those phrasal comparatives in which the standard is syntactically contained inside the target. Presuppositions are usually taken to be li- censed by certain lexical items (presupposition triggers). However, subset comparatives show that presuppositions can also arise as a result of semantic composition. This finding suggests that the grammar possesses more than one way of licensing these inferences. Further research will have to determine how productive this latter strategy is in natural languages. Keywords: Subset comparatives, presuppositions, amount comparatives, degrees. 1. Introduction Amount comparatives are usually discussed with respect to their degree or amount interpretation. This reading is exemplified in the comparative in (1), where the elements being compared are the cardinalities corresponding to the sets of books read by John and Mary respectively: (1) John read more books than Mary. |{x : books(x) ∧ John read x}| ≻ |{y : books(y) ∧ Mary read y}| In this paper, I discuss subset comparatives (Grant (to appear); Grant (2013)), a much less studied type of amount comparative illustrated in the Spanish1 example in (2):2 (2) Juan ha leído más libros que El Quijote. -

Interpretations and Mathematical Logic: a Tutorial

Interpretations and Mathematical Logic: a Tutorial Ali Enayat Dept. of Philosophy, Linguistics, and Theory of Science University of Gothenburg Olof Wijksgatan 6 PO Box 200, SE 405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden e-mail: [email protected] 1. INTRODUCTION Interpretations are about `seeing something as something else', an elusive yet intuitive notion that has been around since time immemorial. It was sys- tematized and elaborated by astrologers, mystics, and theologians, and later extensively employed and adapted by artists, poets, and scientists. At first ap- proximation, an interpretation is a structure-preserving mapping from a realm X to another realm Y , a mapping that is meant to bring hidden features of X and/or Y into view. For example, in the context of Freud's psychoanalytical theory [7], X = the realm of dreams, and Y = the realm of the unconscious; in Khayaam's quatrains [11], X = the metaphysical realm of theologians, and Y = the physical realm of human experience; and in von Neumann's foundations for Quantum Mechanics [14], X = the realm of Quantum Mechanics, and Y = the realm of Hilbert Space Theory. Turning to the domain of mathematics, familiar geometrical examples of in- terpretations include: Khayyam's interpretation of algebraic problems in terms of geometric ones (which was the remarkably innovative element in his solution of cubic equations), Descartes' reduction of Geometry to Algebra (which moved in a direction opposite to that of Khayyam's aforementioned interpretation), the Beltrami-Poincar´einterpretation of hyperbolic geometry within euclidean geom- etry [13]. Well-known examples in mathematical analysis include: Dedekind's interpretation of the linear continuum in terms of \cuts" of the rational line, Hamilton's interpertation of complex numbers as points in the Euclidean plane, and Cauchy's interpretation of real-valued integrals via complex-valued ones using the so-called contour method of integration in complex analysis. -

Arguments Vs. Explanations

Arguments vs. Explanations Arguments and explanations share a lot of common features. In fact, it can be hard to tell the difference between them if you look just at the structure. Sometimes, the exact same structure can function as an argument or as an explanation depending on the context. At the same time, arguments are very different in terms of what they try to accomplish. Explaining and arguing are very different activities even though they use the same types of structures. In a similar vein, building something and taking it apart are two very different activities, but we typically use the same tools for both. Arguments and explanations both have a single sentence as their primary focus. In an argument, we call that sentence the “conclusion”, it’s what’s being argued for. In an explanation, that sentence is called the “explanandum”, it’s what’s being explained. All of the other sentences in an argument or explanation are focused on the conclusion or explanandum. In an argument, these other sentences are called “premises” and they provide basic reasons for thinking that the conclusion is true. In an explanation, these other sentences are called the “explanans” and provide information about how or why the explanandum is true. So in both cases we have a bunch of sentences all focused on one single sentence. That’s why it’s easy to confuse arguments and explanations, they have a similar structure. Premises/Explanans Conclusion/Explanandum What is an argument? An argument is an attempt to provide support for a claim. One useful way of thinking about this is that an argument is, at least potentially, something that could be used to persuade someone about the truth of the argument’s conclusion. -

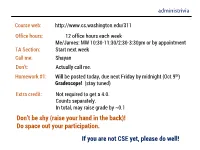

CSE Yet, Please Do Well! Logical Connectives

administrivia Course web: http://www.cs.washington.edu/311 Office hours: 12 office hours each week Me/James: MW 10:30-11:30/2:30-3:30pm or by appointment TA Section: Start next week Call me: Shayan Don’t: Actually call me. Homework #1: Will be posted today, due next Friday by midnight (Oct 9th) Gradescope! (stay tuned) Extra credit: Not required to get a 4.0. Counts separately. In total, may raise grade by ~0.1 Don’t be shy (raise your hand in the back)! Do space out your participation. If you are not CSE yet, please do well! logical connectives p q p q p p T T T T F T F F F T F T F NOT F F F AND p q p q p q p q T T T T T F T F T T F T F T T F T T F F F F F F OR XOR 푝 → 푞 • “If p, then q” is a promise: p q p q F F T • Whenever p is true, then q is true F T T • Ask “has the promise been broken” T F F T T T If it’s raining, then I have my umbrella. related implications • Implication: p q • Converse: q p • Contrapositive: q p • Inverse: p q How do these relate to each other? How to see this? 푝 ↔ 푞 • p iff q • p is equivalent to q • p implies q and q implies p p q p q Let’s think about fruits A fruit is an apple only if it is either red or green and a fruit is not red and green. -

Conditional Statement/Implication Converse and Contrapositive

Conditional Statement/Implication CSCI 1900 Discrete Structures •"ifp then q" • Denoted p ⇒ q – p is called the antecedent or hypothesis Conditional Statements – q is called the consequent or conclusion Reading: Kolman, Section 2.2 • Example: – p: I am hungry q: I will eat – p: It is snowing q: 3+5 = 8 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 1 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 2 Conditional Statement/Implication Truth Table Representing Implication (continued) • In English, we would assume a cause- • If viewed as a logic operation, p ⇒ q can only be and-effect relationship, i.e., the fact that p evaluated as false if p is true and q is false is true would force q to be true. • This does not say that p causes q • If “it is snowing,” then “3+5=8” is • Truth table meaningless in this regard since p has no p q p ⇒ q effect at all on q T T T • At this point it may be easiest to view the T F F operator “⇒” as a logic operationsimilar to F T T AND or OR (conjunction or disjunction). F F T CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 3 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 4 Examples where p ⇒ q is viewed Converse and contrapositive as a logic operation •Ifp is false, then any q supports p ⇒ q is • The converse of p ⇒ q is the implication true. that q ⇒ p – False ⇒ True = True • The contrapositive of p ⇒ q is the –False⇒ False = True implication that ~q ⇒ ~p • If “2+2=5” then “I am the king of England” is true CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 5 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 6 1 Converse and Contrapositive Equivalence or biconditional Example Example: What is the converse and •Ifp and q are statements, the compound contrapositive of p: "it is raining" and q: I statement p if and only if q is called an get wet? equivalence or biconditional – Implication: If it is raining, then I get wet. -

Against Logical Form

Against logical form Zolta´n Gendler Szabo´ Conceptions of logical form are stranded between extremes. On one side are those who think the logical form of a sentence has little to do with logic; on the other, those who think it has little to do with the sentence. Most of us would prefer a conception that strikes a balance: logical form that is an objective feature of a sentence and captures its logical character. I will argue that we cannot get what we want. What are these extreme conceptions? In linguistics, logical form is typically con- ceived of as a level of representation where ambiguities have been resolved. According to one highly developed view—Chomsky’s minimalism—logical form is one of the outputs of the derivation of a sentence. The derivation begins with a set of lexical items and after initial mergers it splits into two: on one branch phonological operations are applied without semantic effect; on the other are semantic operations without phono- logical realization. At the end of the first branch is phonological form, the input to the articulatory–perceptual system; and at the end of the second is logical form, the input to the conceptual–intentional system.1 Thus conceived, logical form encompasses all and only information required for interpretation. But semantic and logical information do not fully overlap. The connectives “and” and “but” are surely not synonyms, but the difference in meaning probably does not concern logic. On the other hand, it is of utmost logical importance whether “finitely many” or “equinumerous” are logical constants even though it is hard to see how this information could be essential for their interpretation. -

Representation and Metaphysics Proper

Richard B. Wells ©2006 CHAPTER 4 First Epilegomenon: Representation and Metaphysics Proper The pursuit of wisdom has had a two-fold origin. Diogenes Laertius § 1. Questions Raised by Representation The outline of representation presented in Chapter 3 leaves us with a number of questions we need to address. In this chapter we will take a look back at our ideas of representation and work toward the resolution of those issues that present themselves in consequence of the theory as it stands so far. I call this look back an epilegomenon, from epi – which means “over” or “upon” – and legein – “to speak.” I employ this new term because the English language seems to have no word that adequately expresses the task at hand. “Epilogue” would imply logical conclusion, while “summary” or “epitome” would suggest a simple re-hashing of what has already been said. Our present task is more than this; we must bring out the implications of representation, Critically examine the gaps in the representation model, and attempt to unite its aggregate pieces as a system. In doing so, our aim is to push farther toward “that which is clearer by nature” although we should not expect to arrive at this destination all in one lunge. Let this be my apology for this minor act of linguistic tampering.1 In particular, Chapter 3 saw the introduction of three classes of ideas that are addressed by the division of nous in its role as the agent of construction for representations. We described these ideas as ideas of the act of representing. -

Truth-Bearers and Truth Value*

Truth-Bearers and Truth Value* I. Introduction The purpose of this document is to explain the following concepts and the relationships between them: statements, propositions, and truth value. In what follows each of these will be discussed in turn. II. Language and Truth-Bearers A. Statements 1. Introduction For present purposes, we will define the term “statement” as follows. Statement: A meaningful declarative sentence.1 It is useful to make sure that the definition of “statement” is clearly understood. 2. Sentences in General To begin with, a statement is a kind of sentence. Obviously, not every string of words is a sentence. Consider: “John store.” Here we have two nouns with a period after them—there is no verb. Grammatically, this is not a sentence—it is just a collection of words with a dot after them. Consider: “If I went to the store.” This isn’t a sentence either. “I went to the store.” is a sentence. However, using the word “if” transforms this string of words into a mere clause that requires another clause to complete it. For example, the following is a sentence: “If I went to the store, I would buy milk.” This issue is not merely one of conforming to arbitrary rules. Remember, a grammatically correct sentence expresses a complete thought.2 The construction “If I went to the store.” does not do this. One wants to By Dr. Robert Tierney. This document is being used by Dr. Tierney for teaching purposes and is not intended for use or publication in any other manner. 1 More precisely, a statement is a meaningful declarative sentence-type. -

Lowe's Eliminativism About Relations and the Analysis Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PhilPapers Lowe’s eliminativism about relations and the analysis of relational inherence Markku Keinänen Tampere University, Finland markku.keinanen[a]tuni.fi https://philpeople.org/profiles/markku-keinanen .[DRAFT, please do not quote] Abstract, Contrary to widely shared opinion in analytic metaphysics, E.J. Lowe argues against the existence of relations in his posthumously published paper There are probably no relations (2016). In this article, I assess Lowe’s eliminativist strategy, which aims to show that all contingent “relational facts” have a monadic foundation in modes characterizing objects. Second, I present two difficult ontological problems supporting eliminativism about relations. Against eliminativism, metaphysicians of science have argued that relations might well be needed in the best a posteriori motivated account of the structure of reality. Finally, I argue that, by analyzing relational inherence, trope theory offers us a completely new approach to relational entities and avoids the hard problems motivating eliminativism. 1. Introduction It has been a widely shared view in analytic metaphysics that we need to postulate relations in order to provide an adequate account of reality. For instance, concrete objects are spatio-temporally related in various ways and the spatio-temporal arrangement of objects is contingent relative to their existence and monadic properties. Here the most straightforward conclusion is that there are additional entities, spatio-temporal relations, which account for objects’ being spatio-temporally related in different ways. Similarly, influential metaphysicians of science have maintained that relations figure among the fundamental constituents of reality according to reasonable interpretation of the best physical theories (Teller 1986, Butterfield 2006). -

Notes on Pragmatism and Scientific Realism Author(S): Cleo H

Notes on Pragmatism and Scientific Realism Author(s): Cleo H. Cherryholmes Source: Educational Researcher, Vol. 21, No. 6, (Aug. - Sep., 1992), pp. 13-17 Published by: American Educational Research Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1176502 Accessed: 02/05/2008 14:02 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aera. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Notes on Pragmatismand Scientific Realism CLEOH. CHERRYHOLMES Ernest R. House's article "Realism in plicit declarationof pragmatism. Here is his 1905 statement ProfessorResearch" (1991) is informative for the overview it of it: of scientificrealism.