MIGUEL FARÍAS — up and Down

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

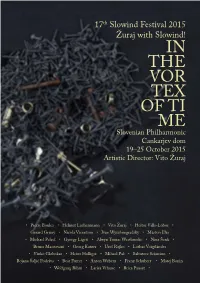

In the Vor Tex of Ti Me

17th Slowind Festival 2015 Žuraj with Slowind! IN THE VOR TEX OF TI Slovenian PhilharmonicME Cankarjev dom 19–25 October 2015 Artistic Director: Vito Žuraj • Pierre Boulez • Helmut Lachenmann • Vito Žuraj • Heitor Villa-Lobos • Gérard Grisey • Nicola Vicentino • Ivan Wyschnegradsky • Márton Illés • Michael Pelzel • György Ligeti • Alwyn Tomas Westbrooke • Nina Šenk • Bruno Mantovani • Georg Katzer • Uroš Rojko • Lothar Voigtländer • Vinko Globokar • Heinz Holliger • Mihael Paš • Salvatore Sciarrino • Bojana Šaljić Podešva • Beat Furrer • Anton Webern • Franz Schubert • Matej Bonin • Wolfgang Rihm • Larisa Vrhunc • Brice Pauset • Valued Listeners, It is no coincidence that we in Slowind decided almost three years ago to entrust the artistic direction of our festival to the penetrating, successful and (still) young composer Vito Žuraj. And it is precisely in the last three years that Vito has achieved even greater success, recently being capped off with the prestigious Prešeren Fund Prize in 2014, as well as a series of performances of his compositions at a diverse range of international music venues. Vito’s close collaboration with composers and performers of various stylistic orientations was an additional impetus for us to prepare the Slowind Festival under the leadership of a Slovenian artistic director for the first time! This autumn, we will put ourselves at the mercy of the vortex of time and again celebrate to some extent. On this occasion, we will mark the th th 90 birthday of Pierre Boulez as well as the 80 birthday of Helmut Lachenmann and Georg Katzer. In addition to works by these distinguished th composers, the 17 Slowind Festival will also present a range of prominent composers of our time, including Bruno Mantovani, Brice Pauset, Michael Pelzel, Heinz Holliger, Beat Furrer and Márton Illés, as well as Slovenian composers Larisa Vrhunc, Nina Šenk, Bojana Šaljić Podešva, Uroš Rojko, and Matej Bonin, and, of course, the festival’s artistic director Vito Žuraj. -

Composition Prize 2013

Concours de Genève Prix international d’ interprétation & de composition Press Kit Composition Prize 2013 Partenaire principal Concours de Genève Prix international d’ interprétation & de composition Table of contents Introduction Page 2 Presentation and regulation Page 3 The Finalists and the works Page 4 Members of the Jury Page 12 Young Audience Prize Page 15 The Ensemble Contrechamps Page 16 Musical Director of Contrechamps Page 17 Partners Page 18 Organisation Page 19 Contact Page 20 Partenaire principal 1 Concours de Genève INTRODUCTION Prix international d’ interprétation & de composition A new discipline The Geneva International Music Competition is traditionally a competition of musical performance. Since 1939, nearly all disciplines have been represented over the years, from orchestra Instruments to chamber music, piano and voice. The only exception was composition, a discipline essential to performers but often ill regarded by the public. Now however, in Geneva, the two worlds now cohabit. By offering a Composition Prize, for which the award winning work will be compulsory for performers the following year, the Geneva International Music Competition hopes to contribute to the emergence of a true musical modernity, whereby the creative act of the composer will be regarded with the same standards of respect and admiration as the re-creative act of the performer. The Geneva Competition’s Composition Prize follows the tradition started with the Prix Reine Marie José, which was awarded from 1958 to 2008 to more than 20 works from diverse disciplines, ranging from quartets to concertos, symphonies to pieces for solo and electronic instruments. With the support of the Fondation Reine Marie José, the Geneva public now has the possibility of watching a performance of the , of awarding the Audience Prize to the piece of its choice and of re-listening to the award-winning work the following year, during the competition performances. -

Composition Prize 2013

Concours de Genève Prix international d’ interprétation & de composition Press Kit Composition Prize 2013 Partenaire principal Concours de Genève Prix international d’ interprétation & de composition Table of contents Introduction Page 2 Presentation and regulation Page 3 The Finalists and their works Page 4 Members of the Jury Page 12 Young Audience Prize Page 15 The Ensemble Contrechamps Page 16 Musical Director of Contrechamps Page 17 Partners Page 18 Organisation Page 19 Contact Page 20 Partenaire principal 1 Concours de Genève INTRODUCTION Prix international d’ interprétation & de composition A new discipline The Geneva International Music Competition is traditionally a competition of musical performance. Since 1939, nearly all disciplines have been represented, from orchestra instruments to chamber music, piano and voice. The only exception was composition, a discipline essential to performers but often ill regarded by the public. Now however, the two worlds cohabit in Geneva. By offering a Composition Prize, for which the award winning work will be compulsory for performers the following year, the Geneva Competition hopes to contribute to the emergence of a true musical modernity, whereby the creative act of the composer will be regarded with the same standards of respect and admiration as the re-creative act of the performer. The Geneva Competition’s Composition Prize follows the tradition started with the Prix Reine Marie José, which was awarded between 1958 and 2008 to more than 20 composers for works ranging from quartet to concertos, symphonies to pieces for solo and electronic instruments. With the support of the Fondation Reine Marie José, our audience now has the possibility of watching these works performed as Word Premiere, of awarding the Audience Prize to the piece of its choice and seeing the award-winning work performed again the following year as one of the competition rounds. -

Composers of the 17Th Slowind Festival 2015 Modern, the Ensemble Intercontemporain, the Minguet Quartet and the Munich Chamber Orchestra

Composers of the 17th Slowind Festival 2015 Modern, the Ensemble Intercontemporain, the Minguet Quartet and the Munich Chamber Orchestra. In 2001 he played the solo part of his piano concerto Rajzok II in the Cologne Philharmonie with the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Jonathan Nott. He has taught theory at Karlsruhe University of Music since 2005 Márton Illés (roj . 1975) and composition at Würzburg University of Music since 2011. His works are Márton Illés, born in Budapest, received published by Breitkopf & Härtel. Among his early training in piano, composition his awards and honours are the Christoph and percussion at various Kodály schools and Stephan Kaske Prize (2005), the in Győr. From 1994 to 2001 he attended composers’ prize of the Ernst von Siemens the Basle Academy of Music, where he Music Foundation (2008), the Schneider- studied with László Gyimesi (piano) and Schott Prize and the Paul Hindemith Detlev Müller-Siemens (composition). Prize. This was followed from 2001 to 2005 by studies in Karlsruhe with Wolfgang Rihm (composition) and Michael Reudenbach (theory). Later he received fellowships to the Villa Massimo in Rome (2009), the Villa Concordia in Bamberg (2011) and the Civitella Ranieri Centre in Umbria (2012). His catalogue of works includes pieces for solo instrument, chamber music, string quartets, vocal works, ensemble compositions, electronic music, two pieces of music theatre and works for string orchestra and full orchestra. He has been performed at leading international festivals and concert halls including the Rome Auditorium, Cité des Arts (Paris), Klangspuren (Schwaz, Austria), Kings Place (London), the Berlin Konzerthaus, Musica Strasbourg, the Munich Biennale, the Schleswig-Holstein Festival, the Tokyo Summer Festival, Ultraschall (Berlin), Eclat Festival (Stuttgart) and the Witten Contemporary Chamber Music Festival. -

Ensemble Contrechamps

Sommaire Ensemble Contrechamps 2 Saison 2019 — 2020 8 Écoute et réflexions 34 Les Éditions Contrechamps 40 Soutiens & partenaires 47 Billetterie 50 Informations pratiques 54 Calendrier général 57 1 Ensemble Ensemble Contrechamps FR Contrechamps est un ensemble de solistes spécialisé dans la création, le développement et la diffusion de la musique Contrechamps instrumentale des XXe et XXIe siècles, depuis plus de quarante ans. L’Ensemble s’engage à décloisonner les merveilles de cette musique ainsi qu’à mettre en valeur la diversité des esthétiques et des acteurs de la scène contemporaine et expérimentale. Depuis sa création, l’Ensemble Contrechamps collabore étroitement avec un grand nombre de compositeurs. On peut citer Pierre Boulez, Rebecca Saunders, Brian Ferneyhough, Beat Furrer, Klaus Huber, Michael Jarrell ou Matthias Pintscher, ainsi qu’une nouvelle génération de créateurs ; Rebecca Glover et Fernando Garnero par exemple. Pour la saison 2019-2020, des œuvres ont été commandées à Chiyoko Szlavnics, Jacques Demierre, Bryn Harrison, Christine Sun Kim, Christopher Trapani, Thomas Ankersmit, Abril Padilla ainsi qu’au groupe Massicot. Les titulaires Antoine Françoise et Simon Aeschimann créent par ailleurs la musique pour une nouvelle pièce chorégraphique de Maud Blandel. Cette saison, Contrechamps organise à nouveau une semaine interdisciplinaire appelée Le Laboratoire et inaugure Le Jet d'eau, un programme de soutien à la prochaine génération. Trois pièces d’étudiants de la Haute école de musique sont créées, et de nombreuses premières suisses présentées. Contrechamps a joué sous la direction d’une multitude de chefs à travers son histoire, de Heinz Holliger à Emilio Pomàrico, Michael Wendeberg, Elena Schwarz ou Clement Power. -

Miguel Farías (*1983)

© Max Sotomayor MIGUEL FARÍAS (*1983) 1 Up & down: Lecturas Críticas (2016) 22:56 1 Laurent Bruttin, clarinet 4 PHACE: for bass / contrabass clarinet and ensemble Ensemble Contrechamps Lars Mlekusch, saxophone Michael Wendeberg, conductor Mathilde Hoursiangou, piano 2 Estelas (2010) 11:59 Berndt Thurner, percussion for clarinet, percussion, piano and violoncello 2 Ensemble Contrechamps: Roland Schueler, cello Laurent Bruttin, clarinet Simeon Pironkoff, conductor 3 CBR (2013) 12:01 François Volpé, percussion for flute, percussion, piano and violoncello Benjamin Kopp, piano 5 Ensemble Vortex: Oliviert Marron, violoncello Anne Gillot, bass clarinet 4 Palettes (2013) 09:03 Max Dazas, percussion for baritone sax, percussion, piano and violoncello 3 Ensemble Zero: Jocelyne Rudasiwa, cembalo Guillermo Lavado, flute Mauricio Carrasco, guitar 5 Une voix liquide (2018) 13:28 Luis Alberto Latorre, piano Hannah Walter, violin for ensemble and electronics Gerardo Salazar, percussion Benoît Morel, viola Celso López, violoncello Aurélien Ferrete, cello TT 69:38 Arturo Corrales, electronics 3 I can imagine that a listener who has nev- er heard of Miguel Farías, might be con- founded by the names of the pieces and performers: is he a French or a Chilean composer? I would argue that, like many Chileans working in contemporary music, Farías is trying to find a place as a cosmo- politan figure. Born in Venezuela, he studied in France and Switzerland, and his music has been premiered and has received sev- The rise of experimental and new music eral awards in both those and many other in Chile is a relatively recent phenome- European countries. What sets Farías aside, non. Since the end of Pinochet’s dictator- both in Chilean and global terms, is the ship there has been an explosion of names, consciousness he brings to that border- festivals, works and opportunities. -

PRESS KIT 69Th Geneva International Music Competition 75Th Anniversary!

Dossier de presse Mercredi 24 septembre 2013 PRESS KIT 69th Geneva International Music Competition 75th Anniversary! Main partner Concours de Genève Prix international d’ interprétation & de composition Table of contents Summary of 2014 edition Page 1 75th Anniversary Page 2 Special projects Important historical dates Regulation Page 6 Prizes and awards Page 7 Candidates - statistics Page 8 Piano competition Page 9 Selected candidates Competition programme Members of the Jury Orchestras Flute competition Page 15 Selected candidates Competition programme Members of the Jury Orchestras Around the Competition Page 22 Career development programme Page 23 Laureates’ international tour 2014 Page 24 A glance at 2015 Page 25 Radio / internet / TV broadcast Page 26 Tickets Page 27 Friends of the Geneva Competition Page 28 Partners Page 29 Organisation Page 30 Contacts Page 31 Concours de Genève SUMMARY OF 2014 Prix international d’ interprétation & de composition DATES 16 November - 5 December 2014 SUBJECT Piano & Flute / 75th Anniversary VENUES (GE, CH) Geneva Conservatory, Victoria Hall, Studio E. Ansermet, Genev’Art Space EVENTS 16 Nov. 75th Anniversary party 6 pm Genev’Art Space 17-19 Nov. Recital I Flute 2 pm/7 pm Conservatory 20-22 Nov. Recital I Piano 2 pm/7 pm Conservatory 22-23 Nov. Recital II Flûte 11 am/2/7pm Studio Ansermet 24-25 Nov. Recital II Piano 11 am/2/7pm Conservatory 26-27 Nov. Semi-final Flute 2 pm/7 pm Conservatory 27-28 Nov. Semi-final Piano 2 pm/7 pm Studio Ansermet 30 Nov. Final I Piano 5 pm Conservatory 01 Dec. Final Flute with L’OCG 8 pm Victoria Hall 02 Dec. -

ENSEMBLE CONTRECHAMPS.Indd

Musique A voir aussi Dasha Rush | The Chronics B2B Chlär | Ensemble Mimetic CH mer 5 sept 23:00 Contrechamps Le Club La Porte des cieux Theater Artemis Oorlog mar 4 sept 19:00 jeu 6 sept 15:00 Temple de Carouge Théâtre Am Stram Gram Coréalisation La Ribot & Dançando com a Diferença Après ce concert, vous ne verrez Happy Island avec l’Ensemble plus votre porte d’entrée de la même Contrechamps ven 7 sept 21:00 manière. La faute à Stockhausen, Le Grütli Durée 60’ compositeur dingue et majeur de l’avant-garde des années 50–60, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande I Julien Leroy fondateur des musiques électroniques Gabriel Schenker et idole de la culture pop. Faits jeu 13 sept 20:00 d’armes : quatuor à cordes en Victoria Hall hélicoptère, opéra dantesque de plusieurs jours et… La Porte des cieux, pour laquelle il fit fabriquer une massive porte en bois contre laquelle un homme toque, gratte, cogne, s’énerve… Une réponse à Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door de Dylan ? Restaurant En prélude, Georgia Rodgers, jeune lauréate du prix Next Wave travaille Avant ou après les spectacles, rendez-vous au sur la perception du son dans l’espace SEPTEMBRE VERT, restaurant de La Bâtie. et s’intéresse pour l’occasion aux sonorités du tuba. Des plats aux saveurs métissées, des recettes Pour finir, l’aventureuse Ann traditionnelles, des produits régionaux, le tout Cleare s’autorise à faire crisser les à déguster seul ou à partager entre amis ! clarinettes. Aux manettes, l’Ensemble Contrechamps et son nouveau Ouvert tous les jours jusqu’au 15 septembre directeur artistique, Serge Vuille, Horaires : 18:00 - 02:00 s’emploient une fois de plus à révéler Service : 19:00 - 01:00 e des merveilles du XXI siècle. -

Download Booklet

1 © Wasik Anita EUNHO CHANG (*1983) 1 String Quartet No. 2 (2011) 13:21 2 White Shadow (2012) for six percussion players 15:37 3 Gohok (2012/13) for solo flute and five instruments 15:24 4 Panorama (2015) for seven instruments 13:39 TT 58:01 1 Arditti Quartet 2 Ensemble TaCTuS 3 Ensemble Contrechamps 4 Divertimento Ensemble Irvine Arditti violin Raphael Aggery percussion Félix Renggli solo flute Lorenzo Gorli violin Ashot Sarkissjan violin Ying-Yu Chang percussion Laurent Bruttin clarinet Daniel Palmizio viola Ralf Ehlers viola Paul Changarnier percussion Sébastien Cordier percussion Martina Rudic cello Lucas Fels cello Quentin Dubois percussion Antoine Françoise piano Lorenzo Missaglia flute Pierre Olympieff percussion Hans Egidi viola Maurizio Longoni clarinet Thibaut Weber percussion Olivier Marron cello Lorenzo Colombo percussion Gregory Charette conductor Maria Grazia Bellocchio piano Sandro Gorli conductor 2 3 Recording dates: 1 24 Jan 2012 2 25 Jul 2012 3 1 Dec 2013 4 24 Oct 2015 Recording venues: 1 Court Room, Senate House, London, United Kingdom 2 Percussion Center L’Hameçon, Lyon, France 3 Studio Ansermet, Geneva, Switzerland 4 Teatro della Terra, Milan, Italy Recording engineers: 1 Colin Still 2 Pierre Olympieff 3 Jan Nehring, Philippe Hamilton (RTS – Espace 2) 4 Divertimento Ensemble Producers: 1 Institute of Musical Research, School of Advanced Study, University of London 2 Ensemble TaCTuS 3 Radio Télévision Suisse 4 Divertimento Ensemble Mastering: Piotr Wieczorek Text: Dariusz Przybylski Graphic Design: Alexander Kremmers (paladino media), cover based on artwork by Enrique Fuentes 4 5 Hypnotising music: About Eunho Chang’s chamber music by Dariusz Przybylski Eunho Chang’s music is, as the composer himself as- serts, a record of his life, a musical diary, souvenirs re- corded in sound. -

EUNHO CHANG Kaleidoscope

EUNHO CHANG Kaleidoscope Arditti Quartet . Ensemble TaCTuS Ensemble Contrechamps . Divertimento Ensemble © Anita Wasik Eunho Chang Eunho EUNHO CHANG (*1983) 1 String Quartet No. 2 (2011) 13:21 2 White Shadow (2012) for six percussion players 15:37 3 Gohok (2012/13) for solo flute and five instruments 15:24 4 Panorama (2015) for seven instruments 13:39 TT 58:01 1 Arditti Quartet 2 Ensemble TaCTuS 3 Ensemble Contrechamps 4 Divertimento Ensemble Irvine Arditti violin Raphael Aggery percussion Félix Renggli solo flute Lorenzo Gorli violin Ashot Sarkissjan violin Ying-Yu Chang percussion Laurent Bruttin clarinet Daniel Palmizio viola Ralf Ehlers viola Paul Changarnier percussion Sébastien Cordier percussion Martina Rudic cello Lucas Fels cello Quentin Dubois percussion Antoine Françoise piano Lorenzo Missaglia flute Pierre Olympieff percussion Hans Egidi viola Maurizio Longoni clarinet Thibaut Weber percussion Olivier Marron cello Lorenzo Colombo percussion Gregory Charette conductor Maria Grazia Bellocchio piano Sandro Gorli conductor 3 Recording dates: 1 24 Jan 2012 2 25 Jul 2012 3 1 Dec 2013 4 24 Oct 2015 Recording venues: 1 Court Room, Senate House, London, United Kingdom 2 Percussion Center L’Hameçon, Lyon, France 3 Studio Ansermet, Geneva, Switzerland 4 Teatro della Terra, Milan, Italy Recording engineers: 1 Colin Still 2 Pierre Olympieff 3 Jan Nehring, Philippe Hamilton (RTS – Espace 2) 4 Divertimento Ensemble Producers: 1 Institute of Musical Research, School of Advanced Study, University of London 2 Ensemble TaCTuS 3 Radio Télévision Suisse 4 Divertimento Ensemble Mastering: Piotr Wieczorek Text: Dariusz Przybylski Graphic Design: Alexander Kremmers (paladino media), cover based on artwork by Enrique Fuentes 4 Hypnotising music: This album, containing four works from About Eunho Chang’s 2011 to 2015, reflects the artist’s current chamber music attitude.