Sudan: Prospects for Democracy Alex De Waal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egyptian Foreign Policy (Special Reference After the 25Th of January Revolution)

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS POLÍTICAS Y SOCIOLOGÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE DERECHO INTERNACIONAL PÚBLICO Y RELACIONES INTERNACIONALES TESIS DOCTORAL Egyptian foreign policy (special reference after The 25th of January Revolution) MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTORA PRESENTADA POR Rania Ahmed Hemaid DIRECTOR Najib Abu-Warda Madrid, 2018 © Rania Ahmed Hemaid, 2017 UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID Facultad de Ciencias Políticas Y Socioligía Departamento de Derecho Internacional Público y Relaciones Internacionales Doctoral Program Political Sciences PHD dissertation Egyptian Foreign Policy (Special Reference after The 25th of January Revolution) POLÍTICA EXTERIOR EGIPCIA (ESPECIAL REFERENCIA DESPUÉS DE LA REVOLUCIÓN DEL 25 DE ENERO) Elaborated by Rania Ahmed Hemaid Under the Supervision of Prof. Dr. Najib Abu- Warda Professor of International Relations in the Faculty of Information Sciences, Complutense University of Madrid Madrid, 2017 Ph.D. Dissertation Presented to the Complutense University of Madrid for obtaining the doctoral degree in Political Science by Ms. Rania Ahmed Hemaid, under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Najib Abu- Warda Professor of International Relations, Faculty of Information Sciences, Complutense University of Madrid. University: Complutense University of Madrid. Department: International Public Law and International Relations (International Studies). Program: Doctorate in Political Science. Director: Prof. Dr. Najib Abu- Warda. Academic Year: 2017 Madrid, 2017 DEDICATION Dedication To my dearest parents may god rest their souls in peace and to my only family my sister whom without her support and love I would not have conducted this piece of work ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor Prof. Dr. Najib Abu- Warda for the continuous support of my Ph.D. -

Sudan: International Dimensions to the State and Its Crisis

crisis states research centre OCCASIONAL PAPERS Occasional Paper no. 3 Sudan: international dimensions to the state and its crisis Alex de Waal Social Science Research Council April 2007 ISSN 1753 3082 (online) Copyright © Alex de Waal, 2007 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Occasional Paper, the Crisis States Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Occasional Paper, or any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Research Centre, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE 1 Crisis States Research Centre Sudan: International Dimensions to the State and its Crisis Alex de Waal Social Science Research Council Overview This paper follows on from the associated essay, “Sudan: What Kind of State? What Kind of Crisis?”1 which concluded that the two dominant characteristics of the Sudanese state are (a) the extreme economic and political inequality between a hyper-dominant centre and peripheries that are weak and fragmented and (b) the failure of any single group or faction within the centre to exercise effective control over the institutions of the state, but who nonetheless can collectively stay in power because of their disproportionate resources. -

Republic of the Sudan Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Republic of the Sudan Ministry of Foreign Affairs DECLARATION BY THE MINISTRY OF FOREIN AFFAIRS OF THE REPUBLIC OF THESLIDAN Pursuant to the republican decree no (148) of 2017 dated 2/3/2017 on the demarcation of the maritime baseline of the Republic of the Sudan on the Red Sea, and which was deposited with UN Secretary General on April 7th 2017, With reference to the declaration of the Government of the Sudan on its objection and rejection of the declaration of the Arab republic of Egypt dated 2nd of May 2017, on the demarcation of it's maritime boundaries, including coordinates which include the maritime zone of the Sudanese Halaeb Triangle, as part of its borders, The Government of the Sudan declares it objection and rejection to what is known as the Agreement on the demarcation of maritime boundaries between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Arab Republic of Egypt signed on April 8th 2016, and which was deposited at the UN records (Treaty Section.. volume 5477), The Government of the Sudan, while objecting to the agreement, reaffirms its rejection to all that the agreement includes on the Delimitation of the Egyptian maritime boundaries which include coordinates of maritime areas that are an integral part of the maritime boundaries of the Sudanese Halaeb Triangle , in consonance with the Sudan's complaint deposited with the UNSC since 1958,and which the Sudan has been renewing annually, and all the correspondences between the Government of the Sudan and the UN Secretary General and the UNSC, on the repeated attacks on the land and people of the Haleaeb Triangle by the Egyptian Occupying Authorities. -

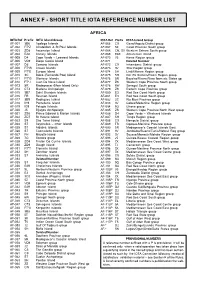

Short Title Iota Reference Number List

RSGB IOTA DIRECTORY ANNEX F - SHORT TITLE IOTA REFERENCE NUMBER LIST AFRICA IOTA Ref Prefix IOTA Island Group IOTA Ref Prefix IOTA Island Group AF-001 3B6 Agalega Islands AF-066 C9 Gaza/Maputo District group AF-002 FT*Z Amsterdam & St Paul Islands AF-067 5Z Coast Province South group AF-003 ZD8 Ascension Island AF-068 CN, S0 Western Sahara South group AF-004 EA8 Canary Islands AF-069 EA9 Alhucemas Island AF-005 D4 Cape Verde – Leeward Islands AF-070 V5 Karas Region group AF-006 VQ9 Diego Garcia Island AF-071 Deleted Number AF-007 D6 Comoro Islands AF-072 C9 Inhambane District group AF-008 FT*W Crozet Islands AF-073 3V Sfax Region group AF-009 FT*E Europa Island AF-074 5H Lindi/Mtwara Region group AF-010 3C Bioco (Fernando Poo) Island AF-075 5H Dar Es Salaam/Pwani Region group AF-011 FT*G Glorioso Islands AF-076 5N Bayelsa/Rivers/Akwa Ibom etc States gp AF-012 FT*J Juan De Nova Island AF-077 ZS Western Cape Province South group AF-013 5R Madagascar (Main Island Only) AF-078 6W Senegal South group AF-014 CT3 Madeira Archipelago AF-079 ZS Eastern Cape Province group AF-015 3B7 Saint Brandon Islands AF-080 E3 Red Sea Coast North group AF-016 FR Reunion Island AF-081 E3 Red Sea Coast South group AF-017 3B9 Rodrigues Island AF-082 3C Rio Muni Province group AF-018 IH9 Pantelleria Island AF-083 3V Gabes/Medenine Region group AF-019 IG9 Pelagie Islands AF-084 9G Ghana group AF-020 J5 Bijagos Archipelago AF-085 ZS Western Cape Province North West group AF-021 ZS8 Prince Edward & Marion Islands AF-086 D4 Cape Verde – Windward Islands AF-022 ZD7 -

New Issues in Refugee Research

NEW ISSUES IN REFUGEE RESEARCH Research Paper No. 254 Refugees and the Rashaida: human smuggling and trafficking from Eritrea to Sudan and Egypt Rachel Humphris Ph.D student COMPAS University of Oxford Email: [email protected] March 2013 Policy Development and Evaluation Service Policy Development and Evaluation Service United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees P.O. Box 2500, 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.unhcr.org These papers provide a means for UNHCR staff, consultants, interns and associates, as well as external researchers, to publish the preliminary results of their research on refugee-related issues. The papers do not represent the official views of UNHCR. They are also available online under ‘publications’ at <www.unhcr.org>. ISSN 1020-7473 Introduction Eritreans have been seeking asylum in east Sudan for more than four decades and the region now hosts more than 100,000 refugees1. East Sudan has also become a key transit region for those fleeing Eritrea. One route, from East Sudan to Egypt, the Sinai desert and Israel has gained increasing attention. According to UNHCR statistics, the number of Eritreans crossing the border from Sinai to Israel has increased from 1,348 in 2006 to 17,175 in 2011. Coupled with this dramatic growth in numbers, the conditions on this route have caused great concern. Testimonies from Eritreans have increasingly referred to kidnapping, torture and extortion at the hands of human smugglers and traffickers. The smuggling route from Eritrea to Israel is long, complex and involves many different actors. As such, it cannot be examined in its entirety in a single paper. -

Re-Describing Transnational Conflict in Africa*

J. of Modern African Studies, , (), pp. – © Cambridge University Press . This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/./), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:./SX Re-describing transnational conflict in Africa* NOEL TWAGIRAMUNGU Boston University, African Studies Center, Bay State Road, Boston, MA , USA; World Peace Foundation Email: [email protected] ALLARD DUURSMA ETH Zurich, Center for Security Studies, Haldeneggsteig , Zürich, Switzerland MULUGETA GEBREHIWOT BERHE World Peace Foundation, Holland St, Suite , Somerville, MA , USA and ALEX DE WAAL World Peace Foundation, Holland St, Suite , Somerville, MA , USA; Tufts University; London School of Economics Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper discusses the principal findings of a new integrated dataset of trans- national armed conflict in Africa. Existing Africa conflict datasets have systematically under-represented the extent of cross-border state support to belligerent parties in internal armed conflicts as well as the number of incidents of covert cross-border * This research was conducted as part of the World Peace Foundation project on African peace missions, funded by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the World Peace Foundation, and as part of the Conflict Research Programme at the London School of Economics, funded by the UK Department for International Development. Their support is gratefully acknowledged. Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.34.90, on 26 Sep 2021 at 10:26:03, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. -

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH/MIDDLE EAST OVERVIEW Human Rights

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH/MIDDLE EAST OVERVIEW Human Rights Developments In the Middle East and North Africa, the overwhelming majority of people lived in countries where basic rights were routinely violated with impunity and where open criticism of the authorities knew sharp limits. This picture changed little during 1997, despite a few hopeful developments that included the Iranian presidential election, the region=s first, excluding Israel, in which the outcome was not known in advance. The battle against Aterrorism@ was invoked by several governments of the region to justify curbs on rights. Without exception, governments that invoked that struggle, including Tunisia, Algeria, Egypt, Israel, and Bahrain, went well beyond justifiable security measures to violate the rights not only of suspected militants but also of peaceful critics and of the population as a whole. All of these governments except Bahrain have ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention against Torture. Yet all violated core rights that are considered nonderogable even in times of national emergency. Religion provided another mantle for the violation of rights. In Iran, an official council of clerics and jurists limited the pool of candidates eligible to run for public office by vetting them for Apiety.@ Pursuant to its interpretation of Islamic (shari=a) law, Saudi Arabia conducted trials in a manner that deprived defendants of their due process rights, while in both Saudi Arabia and Iran courts imposed death by stoning and other forms of severe corporal punishment on offenders. Shari=a-based family and personal status law were used in Iran, Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, and Syria, among others, to discriminate against women, notably in the matters of child custody and in the freedom to marry and to divorce. -

Egypt Relations Further Strained Over Territorial Dispute. the Hala'ib

Sudan- Egypt Relations Further Strained over Territorial Dispute. The Hala’ib Triangle Khartoum takes case before the United Nations amid disagreements over broader regional issues By Abayomi Azikiwe Region: Middle East & North Africa, sub- Global Research, January 11, 2018 Saharan Africa Theme: History, Law and Justice, United Nations Two leading African states, Egypt and Sudan, are maintaining their historical claims over sovereignty of the Hala’ib Triangle. Both nations have argued about whether the area belonged to either of them at least since 1958. On January 8, the Sudanese Foreign Ministry took its complaint to the United Nations. The appeal to the UN followed the withdrawal of the SudaneseForeign Minister Abdel- Mahmoud Abdel Halim from Cairo for consultations on January 4. Egypt suggested that the recall was a hostile move designed to escalate tensions. Egyptian Member of Parliament Mona Mounir seems to have expressed the sentiments of the government saying: “We respect the Sudanese people and their political leadership. However, this escalation (summoning the ambassador) is unjustified.”(Arab News, Jan. 6) She continued emphasizing that Egypt was willing: “to discuss and negotiate everything with neighboring Sudan, except what might affect Egypt’s historic share of the (Nile) water and it’s documented and recognized borders.” Mounir said the recall of Sudanese AmbassadorAbdel Halim “will never deter us from protecting every inch of our territory.” Cairo in 2016 rejected offers of negotiations by Khartoum which was willing to accept international arbitration to determine which state has legal authority to claim Hala’ib Triangle as its national territory. Sudan considers Egypt’s presence in the area as an occupation. -

EGYPT at the Crossroads," Domestic Stability and Regional Role

edited by EGYPT at tJ~e CROSSROADS Domestic Stabilit~ a.b Regional Role EGYPT at the Crossroads," Domestic Stability and Regional Role edited by PHEBE MARR National Defense University Press Washington, DC 1999 T~e IHstitute [or National Strategic Studies The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is a major component of the National Defense University (NDU), which operates under the supervision of the President of NDU. It conducts strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and unified commanders in chief; supports national strategic components of NDU academic programs; and provides outreach to other governmental agencies and the broader national security community. The Publication Directorate of INSS publishes books, monographs, reports, and occasional papers on national security strategy, defense policy, and national military strategy through NDU Press that reflect the output of NDU research and academic programs. In addition, it produces the INSS Strategic Assessment and other work approved by the President of NDU, as well as Joint Force Quarterly, a professional military journal published for the Chairman. Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense, or any other U.S. Government agency. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Portions of this book may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line is included. NDU Press would appreciate a courtesy copy of reprints or reviews. NDU Press publications are sold by the U.S. Government Printing Office. -

IOTA References Réf

IOTA_References List of IOTA References Réf. DXCC Description of IOTA Reference Coordonates AFRICA AF-001 3B6 Agalega Islands (=North, South) 10º00–10º45S - 056º15–057º00E Amsterdam & St Paul Islands (=Amsterdam, Deux Freres, Milieu, Nord, Ouest, AF-002 FT*Z 37º45–39º00S - 077º15–077º45E Phoques, Quille, St Paul) AF-003 ZD8 Ascension Island (=Ascension, Boatswain-bird) 07º45–08º00S - 014º15–014º30W Canary Islands (=Alegranza, Fuerteventura, Gomera, Graciosa, Gran Canaria, AF-004 EA8 Hierro, Lanzarote, La Palma, Lobos, Montana Clara, Tenerife and satellite islands) 27º30–29º30N - 013º15–018º15W Cape Verde - Leeward Islands (aka SOTAVENTO) (=Brava, Fogo, Maio, Sao Tiago AF-005 D4 14º30–15º45N - 022º00–026º00W and satellite islands) AF-006 VQ9 Diego Garcia Island 35º00–36º35N - 002º13W–001º37E Comoro Islands (=Mwali [aka Moheli], Njazidja [aka Grande Comore], Nzwani [aka AF-007 D6 11º15–12º30S - 043º00–044º45E Anjouan]) AF-008 FT*W Crozet Islands (=Apotres Isls, Cochons, Est, Pingouins, Possession) 45º45–46º45S - 050º00–052º30E AF-009 FR/E Europa Island 22º15–22º30S - 040º15–040º30E AF-010 3C Bioco (Fernando Poo) Island 03º00–04º00N - 008º15–009º00E AF-011 FR/G Glorioso Islands (=Glorieuse, Lys, Vertes) 11º15–11º45S - 047º00–047º30E AF-012 FR/J Juan De Nova Island 16º50–17º10S - 042º30–043º00E AF-013 5R Madagascar (main island and coastal islands not qualifying for other groups) 11º45–26º00S - 043º00–051º00E AF-014 CT3 Madeira Archipelago (=Madeira, Porto Santo and satellite islands) 32º35–33º15N - 016º00–017º30W Saint Brandon Islands (aka -

MENA-Atlas - Comments and Sources

MENA-Atlas - Comments and Sources The “Atlas MENA” can be accessed via: http://www.ecoi.net/atlas_mena.pdf The comments and sources for the “Atlas MENA” can be accessed via: http://www.ecoi.net/atlas_mena_sources.pdf Table of contents 1/ General information (for all ethnic and religious maps) 2/ Near East 2.1/ Turkey 2.2/ Syria 2.3/ Iraq 2.4/ Jordan 2.5/ Lebanon 3/ Middle East 3.1/ Afghanistan 3.2/ Pakistan 3.3/ Iran 4/ Arabian Peninsula 4.1/ Saudi Arabia 4.2/ Yemen 4.3/ Oman 5/ North Africa 1 5.1/ Egypt 5.2/ Libya 6/ North Africa 2 6.1/ Algeria 6.2/ Morocco 6.3/ Tunisia 1 For the overview map the following source was used: 1 : 30 000 000: Natural Earth. For all the topographic and thematic maps 1 : 10 000 000: Collins World Explorer Premium, Natural Earth was used. The maps showing main oil and gas fields are all based on: Petroleum Economist, a division of Euromoney Global Limited, December 2014, designed by K. Fuller and P. Bush, map scale 1 : 23 000 000. 1. General information (for all ethnic and religious maps) The population of the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region is very heterogeneously in terms of religious and sectarian, as well as ethnic and linguistic diversity. Due to this and because of the partly inconsistent sources the maps only indicate where main settlement areas of religious or ethnic groups are. Especially the religious and ethnic composition in urban centers may differ significantly from those in rural surroundings and it is not possible to show this heterogeneity on the maps. -

Iota Directory of Islands Regional List British Isles

IOTA DIRECTORY OF ISLANDS sheet 1 IOTA DIRECTORY – QSL COLLECTION Last Update: 22 February 2009 DISCLAIMER: The IOTA list is copyrighted to the Radio Society of Great Britain. To allow us to maintain an up-to-date QSL reference file and to fill gaps in that file the Society's IOTA Committee, a Sponsor Member of QSL COLLECTION, has kindly allowed us to show the list of qualifying islands for each IOTA group on our web-site. To discourage unauthorized use an essential part of the listing, namely the geographical coordinates, has been omitted and some minor but significant alterations have also been made to the list. No part of this list may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise. A shortened version of the IOTA list is available on the IOTA web-site at http://www.rsgbiota.org - there are no restrictions on its use. Islands documented with QSLs in our IOTA Collection are highlighted in bold letters. Cards from all other Islands are wanted. Sometimes call letters indicate which operators/operations are filed. All other QSLs of these operations are needed. EUROPE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND, CHANNEL ISLANDS AND ISLE OF MAN # ENGLAND / SCOTLAND / WALES B EU-005 G, GM, a. GREAT BRITAIN (includeing England, Brownsea, Canvey, Carna, Foulness, Hayling, Mersea, Mullion, Sheppey, Walney; in GW, M, Scotland, Burnt Isls, Davaar, Ewe, Luing, Martin, Neave, Ristol, Seil; and in Wales, Anglesey; in each case include other islands not MM, MW qualifying for groups listed below): Cramond, Easdale, Litte Ross, ENGLAND B EU-120 G, M a.