04 Graham Jones-13.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inheritance and Influence: the Kingdom of the Lombards in Early Medieval Italy

INHERITANCE AND INFLUENCE: THE KINGDOM OF THE LOMBARDS IN EARLY MEDIEVAL ITALY 26 MARCH 2021 READING LIST Judith Herrin Byzantium – the Surprising Life of a Medieval Empire, 2007, Penguin Peter Heather. The Restoration of Rome – Barbarian popes and Imperial Pretenders, 2013, PAN Girolamo Arnaldi Italy and its Invaders, 2002, Harvard University Press. Neil Christie The Lombards – Peoples of Europe Series, 1999, Whiley-Blackwell SLIDE LIST Basilica di San Vitale, Sixth century AD, Ravenna, Italy Bust of Cassius Dio, Second century AD, Museo Nazionale delle Terme di Diocleziano, Rome Peter Paul Rubens and Workshop, Alboin and Rosalind, 1615, Kunsthistorischen Museum, Vienna Longobard Temple, Eighth century AD, Cividale dei Friuli, Italy Umayyad Panel, Eighth century AD, David Museum, Copenhagen Panel with Peacock, Sixth century AD, Archeological Museum, Cividale dei Friuli San Michele Maggiore, Pavia, Italy King Agilulf Helmet Plate, Sixth century AD, Bargello Museum, Florence Fibulae, Sixth century AD, Cividale dei Friuli Silver Plate, Sixth century AD, Cividale dei Friuli Gold Burial Cross, Seventh century AD, Cividale dei Friuli. Garment Brooch, Sixth century AD, Turin Archeological Museum Manuscript from Edit of Rothari, Eighth century copy, Spoleto Public Library Monza Cathedral, Lombardy Chapel of Theodelinda, Fifteenth century, Monza Cathedral, Lombardy Gold book Cover, Seventh century AD, Monza Cathedral Treasury Carlo Saraceni, Inspiration of Saint Gregory, 1959 circa, Burghley House, Lincolnshire, UK Iron Crown of Theodelinda, -

Ilpassaporto

#ILPASSAPORTO PLACES TO GET STAMPS Lombardy is the region with the most UNESCO Sites in Italy. Visit them all! CITIES OF MANTUA Exceptional examples of architecture and urbanism of the Renaissance INFOPOINT MANTOVA – Piazza Mantegna 6, Mantova SABBIONETA INFOPOINT SABBIONETA – Piazza San Rocco 2/b, Sabbioneta (MN) BERNINA REZIA RHAETIAN TRAIN The Bernina Express between the Alps, from Tirano to Saint Moritz INFOPOINT TIRANO – Piazza delle Stazioni, Tirano (SO) ROCK CARVINGS NATIONAL PARK 12,000 years of history etched into the rock INFOPOINT CAPO DI PONTE -Via Nazionale 1, Capo di Ponte (BS) THE SACRED MOUNTS OF PIEDMONT AND LOMBARDY The path that leads to the Sacro Monte of Varese CENTRO ESPOSITIVO MONSIGNOR MACCHI – Viale delle Cappelle, Varese MUSEO BAROFFIO E DEL SANTUARIO – Piazzetta del Monastero, Località Santa Maria del Monte, Varese VIOLIN CRAFTMANSHIP CREMONA The intangible heritage of exceptional artisans MUSEO DEL VIOLINO – Piazza Guglielmo Marconi, Cremona PREHISTORIC ALPINE STILT HOUSES Prehistoric settlements straddling more nations Isolino Virginia – Biandronno (VA) #ILPASSAPORTO MONTE SAN GIORGIO Testimonials of different geological ages between Italy and Switzerland Via Prestini 5, Besano (VA) LOMBARDS IN ITALY: PLACES OF POWER Monastery of Santa Giulia with San Salvatore Basilica and the archaeological area of the Roman Forum Via dei Musei 81/b, Brescia CRESPI D’ADDA WORKERS VILLAGE Important architectural testimony of a historical and social period Associazione Culturale Villaggio Crespi – Piazzale Vittorio Veneto -

Profile of a Plant: the Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE By

Profile of a Plant: The Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE by Benjamin Jon Graham A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Paolo Squatriti, Chair Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes Professor Richard P. Tucker Professor Raymond H. Van Dam © Benjamin J. Graham, 2014 Acknowledgements Planting an olive tree is an act of faith. A cultivator must patiently protect, water, and till the soil around the plant for fifteen years before it begins to bear fruit. Though this dissertation is not nearly as useful or palatable as the olive’s pressed fruits, its slow growth to completion resembles the tree in as much as it was the patient and diligent kindness of my friends, mentors, and family that enabled me to finish the project. Mercifully it took fewer than fifteen years. My deepest thanks go to Paolo Squatriti, who provoked and inspired me to write an unconventional dissertation. I am unable to articulate the ways he has influenced my scholarship, teaching, and life. Ray Van Dam’s clarity of thought helped to shape and rein in my run-away ideas. Diane Hughes unfailingly saw the big picture—how the story of the olive connected to different strands of history. These three people in particular made graduate school a humane and deeply edifying experience. Joining them for the dissertation defense was Richard Tucker, whose capacious understanding of the history of the environment improved this work immensely. In addition to these, I would like to thank David Akin, Hussein Fancy, Tom Green, Alison Cornish, Kathleen King, Lorna Alstetter, Diana Denney, Terre Fisher, Liz Kamali, Jon Farr, Yanay Israeli, and Noah Blan, all at the University of Michigan, for their benevolence. -

Ilpassaporto

#ILPASSAPORTO PLACES TO GET STAMPS The year 2019 marks the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci’s death. Milan and Lombardy will dedicate a whole year to the Maestro. You can get this special stamp at Tourist Infopoint inLombardia! INFOPOINT STANDARD DELLA VALLE IMAGNA Via S. Tomè, 2 INFOPOINT STANDARD BERGAMO CITTÀ ALTA Via Gombito, 13 INFOPOINT STANDARD BERGAMO CITTÀ BASSA Piazzale Marconi INFOPOINT STANDARD CRESPI D'ADDA Via Manzoni, 18 - Località Crespi D'Adda INFOPOINT STANDARD DOSSENA Via Chiesa, 13 INFOPOINT STANDARD ALTO LAGO D'ISEO Piazza Tredici Martiri, 37 INFOPOINT STANDARD MARTINENGO Via Allegreni, 29 INFOPOINT GATE AEROPORTO MILANO/BERGAMO "IL CARAVAGGIO" Via Aeroporto, 13 INFOPOINT STANDARD VALSERIANA E VAL DI SCALVE Via Europa, 111/C INFOPOINT STANDARD BORGHI DELLA PRESOLANA Via Veneto, 3/D INFOPOINT STANDARD SAN PELLEGRINO TERME via San Carlo, 4 INFOPOINT STANDARD BASSO LAGO D'ISEO - VALCALEPIO Via Tresanda, 1 INFOPOINT STANDARD DELLA VALLE BREMBANA via Roma snc INFOPOINT STANDARD ALTOPIANO SELVINO E AVIATICO Corso Milano, 19 INFOPOINT STANDARD DELLA VALCAVALLINA Via Suardi, 20 INFOPOINT STANDARD BASSA BERGAMASCA OCCIDENTALE Piazza Cameroni, 3 INFOPOINT STANDARD VAL BREMBILLA Via Don Pietro Rizzi, 34 INFOPOINT STANDARD BRESCIA - CENTRO Via Trieste, 1 #ILPASSAPORTO INFOPOINT STANDARD BRESCIA - PIAZZA DEL FORO Piazza del Foro, 6 INFOPOINT STANDARD BRESCIA - STAZIONE Via della Stazione, 47 INFOPOINT STANDARD CAPO DI PONTE Via nazionale, 1 INFOPOINT STANDARD FRANCIACORTA Via Carebbio, 32 INFOPOINT STANDARD DARFO BOARIO -

Cultural Tours & Music Holidays

cultural tours & music holidays SPRING NEWSLETTER 2019 Welcome to our new 2019 Cultural Tours & Music Holidays newsletter. We have included a selection of our favourite tours where we still have some places available, as well as details of a Index number of new holidays due to depart in 2019 and early 2020. Cornwall Music Festival 2 We are delighted to reveal details of a six day itinerary to Istanbul in October, a fascinating nine Villa Medici Giulini Collection 3 night tour to Romania, and a holiday to Finland where we attend the annual Sibelius Festival on Verdi Festival, Parma 4 the shores of Lake Lahti. Further afield we shall head to Oman - the ‘Pearl of Arabia’ in October and the beautiful island of Sri Lanka in early 2020. Handel in Sweden 5 Closer to home, we have a range of itineraries within the British Isles, including a tour of the elegant Cheltenham Music Festival 6 architecture of Georgian Dublin (see below), visits to music festivals in Cheltenham, North Norfolk, Aldeburgh Festival 7 Aldeburgh and Suffolk – and our own exclusive Kirker Music Festival in Cornwall. Sibelius Festival 8 In Italy, we will be travelling to some of the most charming and unspoilt towns including Parma in Glyndebourne 9 Emilia-Romagna for the annual Verdi Festival, Lucca in Tuscany, and the hill towns of North Norfolk Music Festival 10 Le Marche. We shall be marking the 400th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci with Kirker Music Festivals 11 a tour to Florence and Milan in the autumn and will commemorate 75 years since the D-Day landings with a tour to Normandy in the company of military historian Hill Towns of Le Marche 12 Hugh Macdonald-Buchanan. -

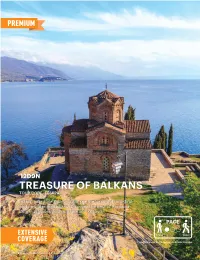

Treasure of Balkans Tour Code: Eeskpa

PREMIUM 12D9N TREASURE OF BALKANS TOUR CODE: EESKPA In this incredible tour you will see the beautiful bountiful and bewildering Balkans. Discover the best of Romania, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Albania and Kosovo. EXTENSIVE COVERAGE ST. JOVAN KANEO OVER OHRID LAKE, MACEDONIA 6 Southern & Eastern Europe | EU Holidays HIGHLIGHTS MACEDONIA Flight path SKOPJE Traverse by coach BULGARIA Featured destinations • House of Mother of 2 ROMANIA Theresa VELIKO TARNOVO Overnight stays 1 2 Brasov • The Church of St. • The Tsarevets 1 Spas Fortress Bran • Mustafa Pasha • Asen’s Monument Sinaia Mosque SOFIA • Fortress Kale • Alexander Nevsky 1 Bucharest OHRID Cathedral SERBIA • Old Town • The Boyana Church MONTENEGRO • Cathedral of St. RILA Sophia • Monastery Sofia 1 Prishtina 1 Veliko Tarnovo ALBANIA ROMANIA Prizren 1 TIRANA SINAIA BULGARIA • Et’hem Bey Mosque • Peles Castle KOSOVO 1 Rila • The Clock Tower BRAN Skopje • Skanderbeg Square • Dracula’s Castle Ohrid Tirana 1 • Skanderbeg Statue BRASOV ALBANIA 1 BERAT • Black Church • Council Square MACEDONIA • Gorica Bridge 1 • Gorica Quarter BUCHAREST Berat • King Mosque • Parliament Palace • The Victory Square KOSOVO • The Roman Square DAY 1 PRIZREN • The Unification HOME → SKOPJE DAY 4 • City Tour Square Meals on Board OHRID → BERAT PRISHTINA Assemble at the airport for your flight to Breakfast, Onufri’s Traditional Lunch, Dinner • City Tour Skopje - The Capital of Macedonia. Hotel breakfast. Heading to the historic city Berat - also known as “the city of a thousand DAY 2 windows”, made the UNESCO World Heritage SKOPJE list in 2008. Explore Berat city tour - the ancient DELICACIES Lunch , Dinner history of Albania from Roman period to modern Meal Plan Explore Skopje with a walking tour of the times. -

1. World Heritage Property Data 2. Statement of Outstanding Universal Value

Periodic Report - Second Cycle Section II-Boyana Church 1. World Heritage Property Data 2. Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 1.1 - Name of World Heritage Property 2.1 - Statement of Outstanding Universal Value / Boyana Church Statement of Significance 1.2 - World Heritage Property Details Statement of Outstanding Universal Value State(s) Party(ies) Brief synthesis There are several layers of wall paintings in the interior from Bulgaria the 11th, 13th, 15-17th and 19th centuries which testify to the Type of Property high level of wall painting during the different periods. The cultural paintings with the most outstanding artistic value are those Identification Number from 13th century. Whilst they interpret the Byzantine canon, the images have a special spiritual expressiveness and vitality 42 and are painted in harmonious proportions. Year of inscription on the World Heritage List Criterion (ii): From an architectural point of view, Boyana 1979 Church is a pure example of a church with a Greek cross ground-plan with dome, richly decorated facades and 1.3 - Geographic Information Table decoration of ceramic elements. It is one of the most remarkable medieval monuments with especially fine wall Name Coordinates Property Buffer Total Inscription (latitude/longitude) (ha) zone (ha) year paintings. (ha) Criterion (iii): The Boyana Church is composed of three Boyana 42.65 / 23.267 0.68 13.55 14.23 1979 parts, each built at a different period - 10 century, 13th century Church and 19th century which constitute a homogenous whole. Total (ha) 0.68 13.55 14.23 Integrity The integrity of Boyana church is fully assured. -

The Cathedral Builders

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES ITHACA, N. Y. 14853 JOHN M. OUN LIBRARY NA5613.B3T"""''"'"'"-"'"^^ ''!'|« "'Ijedral builders; the story of a gr 3 1924 008 738 340 .„.. All books are subject to recall after two weeks Olin/Kroch Library DATE DUE Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924008738340 Of this Edition on Hand-made paper One Hundred Copies only have been printed, of which this is No. M.3....... THE CATHEDRAL BUILDERS THE CATHEDRAL BUILDERS THE STORT OF A GREAT MASONIC GUILD BY LEADER SCOTT Honorary Member of the ' Accademia dalle Belle Arti,' Florence Author of ' The Renaissance of Art in Italy,' ' Handbook of Sculpture,' ' Echoes of Old Florence,' etc. With Eighty Illustrations LONDON SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON AND COMPANY LIMPTED St. Sunstan's 1|ous( Fetter Lane, Fleet Street, E.C. 1899 Richard Clay & Sons, Limi^ted, London & Bungay. — ^ PROEM In most histories of Italian art we are conscious of a vast hiatus of several centuries, between the ancient classic art of Rome—which was in its decadence when the Western Empire ceased in the fifth century after Christ—and that early rise of art in the twelfth century which led to the Renaissance. This hiatus is generally supposed to be a time when Art was utterly dead and buried, its corpse in Byzantine dress lying embalmed in its tomb at Ravenna. But all death is nothing but the germ of new life. -

BULGARIA DISCOVERED GUIDE on the Cover: Lazarka, 46/55 Oils Cardboard, Nencho D

Education and Culture DG Lifelong Learning Programme BULGARIA DISCOVERED GUIDE On the cover: Lazarka, 46/55 Oils Cardboard, Nencho D. Bakalski Lazarka, this name is given to little girls, participating in the rituals on “Lazarovden” – a celebration dedicated to nature and life’ s rebirth. The name Lazarisa symbol of health and long life. On the last Saturday before Easter all Lazarki go around the village, enter in every house and sing songs to each family member. There is a different song for the lass, the lad, the girl, the child, the host, the shepherd, the ploughman This tradition can be seen only in Bulgaria. Nencho D. BAKALSKI is a Bulgarian artist, born in September 1963 in Stara Zagora. He works in the field of painting, portraits, iconography, designing and vanguard. He is a member of the Bulgarian Union of Artists, the branch of Stara Zagora. Education and Culture DG Lifelong Learning Programme BULGARIA DISCOVERED GUIDE 2010 Human Resource Development Centre 2 Rachenitsa! The sound of bagpipe filled the air. The crowd stood still in expectation. Posing for a while against each other, the dancers jumped simultaneously. Dabaka moved with dexterity to Christina. She gently ran on her toes passing by him. Both looked at each other from head to toe as if wanting to show their superiority and continued their dance. Christina waved her white hand- kerchief, swayed her white neck like a swan and gently floated in the vortex of sound, created by the merry bagpipe. Her face turned hot… Dabaka was in complete trance. With hands freely crossed on his back he moved like a deer performing wondrous jumps in front of her … Then, shaking his head to let the heavy sweat drops fall from his face, he made a movement as if retreating. -

Discover Bulgaria Is Famous for Its 600 Healing Mineral Water Springs

Bulgaria Discover Ministry of Economy, Energy and Tourism Bulgaria, 1052 Sofia, 8 Slavyanska Str., Tel. +359 2 94071, fax: +359 2 987 2190 е-mail: [email protected] Bulgaria www.mee.government.bg www.bulgariatravel.org This document is created within the framework of the project “Elaboration and distribution of advertising and informational materials for promotion of Bulgaria as a tourism destination”, Agreement BG161PO001/3.3-01-4, realized with the financial support of Operational Programme “Regional development” 2007 – 2013, co-financed by the European Union through the European Fund for Regional Development. All responsibility for the contents of this document is borne by the beneficiary – the Ministry of Economy, Energy and Tourism and in no circumstances it should be regarded that this document reflects the official position of the European Union and the Governing Authority. USEFULL INFORMATION Bulgaria State government system: Parliamentary Republic Capital city: Sofia (population 1.2 million) Official language: Bulgarian, script – Cyrillic Religion: Orthodox (85%), Muslim (8%), other (7%) Time zone: GMT (London) + 2, Eastern Europe time (Germany) + 1 Climate: Humid continental, in the southern parts – transitive Mediterranean. Average temperatures for January are from -2 to 2 Сo in the lowland and -10 Сo in the mountains, in July 19-25 degrees Сo in the lowland and about 10 degrees Сo in the higher parts of the mountains. BULGARIARainfall - 450-600 mm in the lowland, up to 1300 mm in the mountains. Currency: Bulgarian lev -

Sofia Holy Mount Balsha Monastery of Shiyakovtsi Monastery St Theodore Stratelates of St Michael Katina Monastery the Archangel of the Holy Forty Martyrs

SOFIA HOLY MOUNT BALSHA MONASTERY OF SHIYAKOVTSI MONASTERY ST THEODORE STRATELATES OF ST MICHAEL KATINA MONASTERY THE ARCHANGEL OF THE HOLY FORTY MARTYRS St Gabriel the Archangel, fresco, Boyana Church, 11th century 6 ILIENTSI MONASTERY OF 7 ST ELIJAH THE PROPHET KLISURA MONASTERY OF ST PETKA ORLANDOVTSI SUHODOL MONASTERY MONASTERY OF THE 8 OF THE HOLY TRINITY THREE SAINTS DIVOTINO MONASTERY OF THE HOLY TRINITY SOFIA HOLY MOUNT – North 01 Sofia’s surrounding areas have been conditionally divided in two: this map shows the monasteries in its northern part, while those in the southern part are shown at the end of the brochure. The monasteries we present herewith are marked in red. PODGUMER MONASTERY KURILO OF ST DIMITAR MONASTERY OF ST JOHN OF RILA SESLAVTSI MONASTERY 2 OF ST NICHOLAS 1 KREMIKOVTSI MONASTERY ELESHNITSA MONASTERY OF ST GEORGE 3 OF ST VIRGIN MARY OBRADOVTSI BUHOVO BUHOVO MONASTERY MONASTERY MONASTERY OF ST OF ST MICHAEL THE 5 OF ST MINA MARY MAGDALENE ARCHANGEL CHEPINTSI MONASTERY OF THE THREE SAINTS CHELOPECH MONASTERY OF ST VIRGIN MARY 4 SOFIA GORNI BOGROV MONASTERY OF ST GEORGE 02 SOFIA HOLY MOUNT A Halo of Holiness Around the City of God’s Wisdom SOFIA HOLY MOUNT is a name given to a string of about 40 monasteries in the vicinity of Sofia, a circle of sanctity shining like a nimbus around the city that bears the name of God’s Wisdom. They were founded at various times – from the 4th to the 20th century. They are in different states of preservation – from completely destroyed to fully functioning. -

1.1 Document on Historical /Architectural/Environmental

Ref. Ares(2016)1596182 - 04/04/2016 D1.1 – Document on historical /archi- tectural/environmental knowledge of the buildings Project Information Grant Agreement Number 646178 Nanomaterials for conservation of European architectural heritage developed by Project Full Title research on characteristic lithotypes Project Acronym NANO-CATHEDRAL NMP-21-2014 Materials-based solutions for protection or preservation of Funding scheme European cultural heritage Start date of the project June, 1 2015 Duration 36 months Project Coordinator Andrea Lazzeri (INSTM) Project Website www.nanocathedral.eu Deliverable Information Deliverable n° D1.1 Deliverable title Document on historical/architectural/environmental knowledge of the buildings WP no. 1 WP Leader Marco Lezzerini (INSTM) CONSORZIO INTERUNIVERSITARIO NAZIONALE PER LA SCIENZA E TECNOLOGIA DIE MATERIALI, Opera della Primaziale Pisana, HDK, UNI BA, Fundación Catedral Contributing Partners Santa María, Dombausekretariat St.Stephan, TU WIEN, Architectenbureau Bressers, Statsbygg Nature public Authors Franz Zehetner, Marco Lezzerini, Michele Marroni, Francesca Signori Marco Lezzerini, Michele Marroni, Francesca Signori, Graziana Maddalena Gianluca De Felice, Anton Sutter, Donatella De Bonis, Roberto Cela Ulrike Brinckmann, Sven Eversberg, Peter Fuessenich, Sophie Hoepner Rainer Drewello Contributors Leandro Camara, Juan Ignacio Lasagabaster Wolfgang Zehetner, Franz Zehetner Andreas Rohatsch, Matea Ban Ignace Roelens, Matthias De Waele, Philippe Depotter, Maarten Van Landeghem Resty Garcia, Yngve Kvame Reviewers Marco Lezzerini, Francesca Signori Contractual Deadline Month 4 (Oct 2015) Delivery date to EC April 4, 2016 1/308 Dissemination Level PU Public PP Restricted to other programme participants (incl. Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (incl. Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for the members of the consortium (incl.