University of Dundee DOCTOR OF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lord Lyon King of Arms

VI. E FEUDAE BOBETH TH F O LS BABONAG F SCOTLANDO E . BY THOMAS INNES OP LEABNEY AND KINNAIRDY, F.S.A.ScoT., LORD LYON KIN ARMSF GO . Read October 27, 1945. The Baronage is an Order derived partly from the allodial system of territorial tribalis whicn mi patriarce hth h hel s countrydhi "under God", d partlan y froe latemth r feudal system—whic e shale wasw hse n li , Western Europe at any rate, itself a developed form of tribalism—in which the territory came to be held "of and under" the King (i.e. "head of the kindred") in an organised parental realm. The robes and insignia of the Baronage will be found to trace back to both these forms of tenure, which first require some examination from angle t usuallno s y co-ordinatedf i , the later insignia (not to add, the writer thinks, some of even the earlier understoode symbolsb o t e )ar . Feudalism has aptly been described as "the development, the extension organisatione th y sa y e Family",o familyth fma e oe th f on n r i upon,2o d an Scotlandrelationn i Land;e d th , an to fundamentall o s , tribaa y l country, wher e predominanth e t influences have consistently been Tribality and Inheritance,3 the feudal system was immensely popular, took root as a means of consolidating and preserving the earlier clannish institutions,4 e clan-systeth d an m itself was s modera , n historian recognisew no s t no , only closely intermingled with feudalism, but that clan-system was "feudal in the strictly historical sense".5 1 Stavanger Museums Aarshefle, 1016. -

VETTORI, Winner Oflast Sunday's Prix Du Calvados (G3), Isfrom Thefirst Crop By

TRe TDN is delivered each morning by 5 a.m. Eastern. For subscription information, please call 1732) 747-8060 ^ THOROUGHBRED Sunday, DAILY NEWS" September 5, 1999 A INTERNATIONAL a "HIGH" HOPES SOPHOMORE SET TOPS PRIX DU MOULIN Trainer D. Wayne Lukas has another star In his barn. Three-year-olds dominate today's Gl Emirates Prix du This time it's the $1,050,000 yearling purchase High Moulin de Longchamp, the penultimate European mile Yield (Storm Cat), who cruised to a five-length victory championship event, with only the Gl Queen Elizabeth in the Gl Hopeful S. at Saratoga yesterday afternoon. II S. at Ascot Sept. 25 yet to come. The Prix du Moulin Owned by a partnership comprised of Bob and Beverly features a re-match between Sendawar (Ire) (Priolo) and Lewis, Mrs. John Magnier and Michael Tabor, the Aljabr (Storm Cat), who were separated by only 11/4 flashy chestnut was third in the July 18 Gill Hollywood lengths when first and second, respectively, in the Gl Juvenile Championship in his second start, then St James's Palace S. over a mile at Royal Ascot June shipped east and posted an eye-catching 8 3/4-length 15. Aljabr was making his first start of the season after victory in a Saratoga maiden test Aug. 7. The 9-5 an aborted trip to the U.S. for the Kentucky Derby, Hopeful favorite in the absence of More Than Ready, he while Sendawar had previously won the Gl Dubai Poule broke well, stalked the pace from the inside, angled out d'Essai des Poulains (French 2000 Guineas) May 16, for running room around the turn to carry jockey Jerry beating Danslli (GB) (Danehill) by 1 1/2 lengths. -

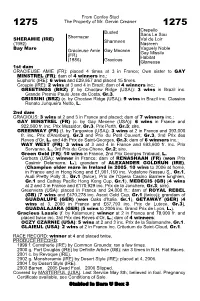

From Confey Stud the Property of Mr. Gervin Creaner Busted

From Confey Stud 1275 The Property of Mr. Gervin Creaner 1275 Crepello Busted Sans Le Sou Shernazar Val de Loir SHERAMIE (IRE) Sharmeen (1992) Nasreen Bay Mare Vaguely Noble Gracieuse Amie Gay Mecene Gay Missile (FR) Habitat (1986) Gracious Glaneuse 1st dam GRACIEUSE AMIE (FR): placed 4 times at 3 in France; Own sister to GAY MINSTREL (FR); dam of 4 winners inc.: Euphoric (IRE): 6 wins and £29,957 and placed 15 times. Groupie (IRE): 2 wins at 3 and 4 in Brazil; dam of 4 winners inc.: GREETINGS (BRZ) (f. by Choctaw Ridge (USA)): 3 wins in Brazil inc. Grande Premio Paulo Jose da Costa, Gr.3. GRISSINI (BRZ) (c. by Choctaw Ridge (USA)): 9 wins in Brazil inc. Classico Renato Junqueira Netto, L. 2nd dam GRACIOUS: 3 wins at 2 and 3 in France and placed; dam of 7 winners inc.: GAY MINSTREL (FR) (c. by Gay Mecene (USA)): 6 wins in France and 922,500 fr. inc. Prix Messidor, Gr.3, Prix Perth, Gr.3; sire. GREENWAY (FR) (f. by Targowice (USA)): 3 wins at 2 in France and 393,000 fr. inc. Prix d'Arenberg, Gr.3 and Prix du Petit Couvert, Gr.3, 2nd Prix des Reves d'Or, L. and 4th Prix de Saint-Georges, Gr.3; dam of 6 winners inc.: WAY WEST (FR): 3 wins at 3 and 4 in France and 693,600 fr. inc. Prix Servanne, L., 3rd Prix du Gros-Chene, Gr.2; sire. Green Gold (FR): 10 wins in France, 2nd Prix Georges Trabaud, L. Gerbera (USA): winner in France; dam of RENASHAAN (FR) (won Prix Casimir Delamarre, L.); grandam of ALEXANDER GOLDRUN (IRE), (Champion older mare in Ireland in 2005, 10 wins to 2006 at home, in France and in Hong Kong and £1,901,150 inc. -

Rock and Mineral Identification for Engineers

Rock and Mineral Identification for Engineers November 1991 r~ u.s. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration acid bottle 8 granite ~~_k_nife _) v / muscovite 8 magnify~in_g . lens~ 0 09<2) Some common rocks, minerals, and identification aids (see text). Rock And Mineral Identification for Engineers TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................ 1 Minerals ...................................................................................... 2 Rocks ........................................................................................... 6 Mineral Identification Procedure ............................................ 8 Rock Identification Procedure ............................................... 22 Engineering Properties of Rock Types ................................. 42 Summary ................................................................................... 49 Appendix: References ............................................................. 50 FIGURES 1. Moh's Hardness Scale ......................................................... 10 2. The Mineral Chert ............................................................... 16 3. The Mineral Quartz ............................................................. 16 4. The Mineral Plagioclase ...................................................... 17 5. The Minerals Orthoclase ..................................................... 17 6. The Mineral Hornblende ................................................... -

Michigan Connected and Automated Vehicle Working Group June 3, 2016

Michigan Connected and Automated Vehicle Working Group June 3, 2016 Meeting Packet 1. Agenda 2. Meeting Notes 3. Attendance List 4. Presentations Michigan Connected and Automated Vehicle Working Group June 3, 2016 Intelligent Ground Vehicle Competition Oakland University Rochester, MI 48309-4401 Meeting Agenda 11:30 AM Lunch and Networking 11:45 AM Welcome and Introductions Adela Spulber, Transportation Systems Analyst, Center for Automotive Research Gerald Lane, Co-Chairman & Co-Founder, IGVC 12:30 PM Connected Vehicle Virtual Trade Show Linda Daichendt, Executive President/Director, Mobile Technology Association of Michigan 12:50 PM Overview of the American Center for Mobility (i.e., Willow Run test site) Andrew Smart, CTO, American Center for Mobility 01:10 PM From Park Assist to Automated Driving Amine Taleb, Manager - Advanced Projects, Valeo North America Inc. 01:30 PM Advanced Vehicle Automation and Convoying Programs at TARDEC Bernard Theisen, Engineer, TARDEC 01:50 PM Overview of the SAE Battelle CyberAuto Challenge Karl Heimer, Founder/Partner, AutoImmune (and co-founder of the Challenge) 02:10 PM Continental – Oakland University Joint Project on ADAS Test & Validation Irfan Baftiu, Engineering Supervisor, Continental Automotive Systems 02:30 PM Watch IGVC teams practice and test on the course 03:00 PM Adjourn Michigan Connected and Automated Vehicle Working Group The Michigan Connected and Automated Vehicle Working Group held a special edition meeting on June 3rd 2016, during Intelligent Ground Vehicle Competition (IGVC) at the Oakland University in Rochester, Michigan. Meeting Notes Adela Spulber, Transportation Systems Analyst at the Center for Automotive Research (CAR), started the meeting by detailing the agenda of the day and working group mission. -

Draft Assessment Report Application A490 Exemption

1 October 2008 [17-08] DRAFT ASSESSMENT REPORT APPLICATION A490 EXEMPTION OF ALLERGEN DECLARATION FOR ISINGLASS DEADLINE FOR PUBLIC SUBMISSIONS: 6pm (Canberra time) 12 November 2008 SUBMISSIONS RECEIVED AFTER THIS DEADLINE WILL NOT BE CONSIDERED (See ‘Invitation for Public Submissions’ for details) For Information on matters relating to this Assessment Report or the assessment process generally, please refer to http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/standardsdevelopment/ Executive Summary Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) received an unpaid Application from the Beer, Wine and Spirits Council of New Zealand (BWSCNZ) in 2003 seeking to amend the Table to clause 4 of Standard 1.2.3 – Mandatory Warning and Advisory Statements and Declarations, of the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code (the Code). Specifically, the Applicant is seeking an exemption from the requirement to declare isinglass (a processing aid commonly derived from dried swim bladders of certain tropical and subtropical fish) on the label, when present in beer and wine as a result of its use as a clarifying agent. The exemption was initially sought on the basis that isinglass has a long history of use as a fining agent in the production of beer and wine and has not been known to cause adverse reactions in susceptible individuals. The Applicant has now provided evidence that dietary exposure to isinglass through beer and wine consumption is extremely low. Results of oral challenge studies have also been provided indicating that isinglass does not cause an allergic reaction to fish sensitive individuals when consumed at levels substantially higher than the potential exposure levels that may be encountered through the consumption of beer and wine. -

ISIS in Yemen: Redoubt Or Remnant? Challenges and Options for Dealing with a Jihadist Threat in a Conflict Environment

JOURNAL OF SOUTH ASIAN AND MIDDLE EASTERN STUDIES ISIS in Yemen: Redoubt or Remnant? Challenges and Options for Dealing with a Jihadist Threat in a Conflict Environment by NORMAN CIGAR Abstract: The emergence of ISIS has represented a significant security risk to U.S. interests and to regional states. In Yemen, the ISIS threat has evolved within Occasional Paper #1 the country’s devastating civil war and, while its lethality has declined, this study Villanova University suggests it remains a factor of concern, Villanova, PA and assesses the challenges and options available for the US and for the November 2020 international community for dealing with this threat. ISIS in Yemen: Redoubt or Remnant? Challenges and Options for Dealing with a Jihadist Threat in a Conflict Environment by Norman Cigar “The fight against terrorism is far from over” Leon E. Panetta, Former Director CIA, 25 August 20191 Introduction and Terms of Reference Even in its short history, the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) has posed a significant security challenge both to U.S. interests and to regional states. As the ISIS Caliphate disintegrated recently in its heartland of Iraq and Syria under a succession of blows by its international and local adversaries, the focus of the international community often shifted to ISIS’s outlying branches. However, contrary to early optimism, ISIS has proved a stubborn survivor even in its Iraq-Syria core, while its presence in branches or affiliates in areas such as the Sinai, the Sahara, West Africa, Mozambique, Yemen, and Khurasan (Afghanistan/Pakistan) also continues to be a significant security threat to local and international interests.2 Moreover, each theater of operations presents a unique set of characteristics, complicating the fight against such local ISIS branches. -

HIV/AIDS Guidelines

Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV Downloaded from https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines on 1/10/2020 Visit the AIDSinfo website to access the most up-to-date guideline. Register for e-mail notification of guideline updates at https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/e-news. Downloaded from https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines on 1/10/2020 Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV Developed by the DHHS Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents – A Working Group of the Office of AIDS Research Advisory Council (OARAC) How to Cite the Adult and Adolescent Guidelines: Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/ AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed [insert date] [insert page number, table number, etc. if applicable] It is emphasized that concepts relevant to HIV management evolve rapidly. The Panel has a mechanism to update recommenda- tions on a regular basis, and the most recent information is available on the AIDSinfo Web site (http://aidsinfo.nih.gov). Downloaded from https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines on 1/10/2020 What’s New in the Guidelines? (Last updated December 18, 2019; last reviewed December 18, 2019) Antiretroviral Therapy to Prevent Sexual Transmission of HIV (Treatment as Prevention) Clinical trials have shown that using effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) to consistently suppress plasma HIV RNA levels to <200 copies/mL prevents transmission of HIV to sexual partners. -

2020 International List of Protected Names

INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (only available on IFHA Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 03/06/21 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org The list of Protected Names includes the names of : Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally renowned, either as main stallions and broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or jump) From 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf Since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf The main stallions and broodmares, registered on request of the International Stud Book Committee (ISBC). Updates made on the IFHA website The horses whose name has been protected on request of a Horseracing Authority. Updates made on the IFHA website * 2 03/06/2021 In 2020, the list of Protected -

HEADLINE NEWS • 9/20/09 • PAGE 2 of 16

Biomechanics & Cardio Scores HEADLINE for Yearlings, 2YOs, Racehorses, Mares & Stallions NEWS BreezeFigs™ at the Two-Year-Old Sales For information about TDN, DATATRACK call 732-747-8060. www.biodatatrack.com www.thoroughbreddailynews.com SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 20, 2009 Bob Fierro • Jay Kilgore • Frank Mitchell MOREAU OF THE SAME AT SEPTEMBER Numbers remained down during the fifth session of the Keeneland September Sale in Lexington, but there were some bright spots in the depressed market, espe- cially in the arena of weanling- to-yearling pinhooks, which ac- counted for the top five horses SIMPLY ‘D’ BEST sold. That included the session Paul Pompa Jr=s D= Funnybone (D=wildcat) was topper, a colt by Bernstein who heavily backed at 2-5 in yesterday=s GII Futurity S. at was purchased by bloodstock Belmont Park following a runaway agent Mike Ryan for $475,000. victory in the GII Saratoga Special It was a feel-good pinhooking S. Aug. 20, and lived up to the coup for the small Ocala-based billing with a good-looking 4 3/4- operation Moreau Bloodstock length tally over Discreetly Mine International, the nom de course (Mineshaft). AI was very im- of husband-and-wife team of pressed,@ trainer Rick Dutrow Jr Xavier and Sharon Moreau. offered. AHe had to show up on The Moreaus, along with part- Xavier Moreau L Marquardt this track going a little further and ners Jean-Philippe Truchement Horsephotos deal with some tough customers, and Irwin and France Weiner, purchased the colt for and he showed up the right way.@ just $55,000 last year at Keeneland November and And if the conditioner had his way? AI=d rather run him offered him here under the Moreau Bloodstock banner. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STRFFT AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 737-4215/842-6353 Revised: July 1985 EXHIBITION FACT SHEET Title: THE TREASURE HOUSES OF BRITAIN: FIVE HUNDRED YEARS OF PRIVATE PATRONAGE AND ART COLLECTING Patrons; Their Royal Highnesses The Prince and Princess of Wales Dates: November 3, 1985 through March. 16, 1986. (This exhibition will not travel. Most loans from houses open to view are expected to remain in place until the late suitmer of 1985 and to be returned before many of the houses open for their visitors in the spring of 1986.) Credits: This exhibition is made possible by a generous grant from the Ford Motor Company. The exhibition was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in collaboration with the British Council and is supported by indemnities from Her Majesty's Treasury and the U.S. Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. Further British assistance was supplied by the National Trust and the Historic Houses Association. British Airways has been designated the official carrier of the exhibition. History of the exhibition; The idea that the National Gallery of Art consider holding a major exhibition devoted to British art evolved in discussions with the British Council in 1979. J. Carter Brown, Director of the National Gallery of Art, proposed an exhibition on the British country house as a "vessel of civilization," bringing together works of art illustrating the extraordinary achievement of collecting and patronage throughout Britain over the past five hundred years. As this concept carried with it the additional, contemporary advantage of stimulating greater interest in and support of those houses open to public viewing, it was enthusiastically endorsed by the late Lord Howard of Henderskelfe, then-Chairman of the Historic Houses Association, Julian Andrews, Director of the Fine Arts Department of the British Council, and Lord Gibson, Chairman of the National Trust. -

The Gladiator Jug from Ismant El-Kharab 291

The Gladiator Jug from Ismant el-Kharab 291 The Gladiator Jug from Ismant el-Kharab Colin A. Hope and Helen V. Whitehouse The excavations at Ismant el-Kharab, ancient Kellis, since 1). The enclosure contains the West Church and its 1986 have produced a considerable quantity of glass of a adjacent complex dated to the mid-fourth century (Bowen wide variety of types,1 including plain and decorated 2002, 75–81, 83), to the east of which are the two West wares.2 On 2 February 2000, however, a quite exceptional Tombs (Hope and McKenzie 1999); slightly to the east of discovery of two adjacent deposits of glass was made these there is a two-roomed mud-brick structure (Hope within Enclosure 4 of Area D, amongst one of which were this volume, Figure 11). At various locations within the fragments from a jug painted with well-preserved scenes enclosure are east-west-oriented, single human burials of combatant gladiators (Hope 2000, 58–9). This vessel presumed to be those of Christians (Bowen this volume; forms the focus of the present contribution, which aims to Hope this volume). The West Tombs predate the place the piece within its broader context and to explore construction of the wall of Enclosure 4, which, in its north- the question of its place of manufacture.3 The vessels that western corner, is identical with the wall of the West comprise the two groups were all found in fragments, not Church. This indicates that the enclosure is contemporary all of which from each vessel were recovered.