The Gladiator Jug from Ismant El-Kharab 291

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lord Lyon King of Arms

VI. E FEUDAE BOBETH TH F O LS BABONAG F SCOTLANDO E . BY THOMAS INNES OP LEABNEY AND KINNAIRDY, F.S.A.ScoT., LORD LYON KIN ARMSF GO . Read October 27, 1945. The Baronage is an Order derived partly from the allodial system of territorial tribalis whicn mi patriarce hth h hel s countrydhi "under God", d partlan y froe latemth r feudal system—whic e shale wasw hse n li , Western Europe at any rate, itself a developed form of tribalism—in which the territory came to be held "of and under" the King (i.e. "head of the kindred") in an organised parental realm. The robes and insignia of the Baronage will be found to trace back to both these forms of tenure, which first require some examination from angle t usuallno s y co-ordinatedf i , the later insignia (not to add, the writer thinks, some of even the earlier understoode symbolsb o t e )ar . Feudalism has aptly been described as "the development, the extension organisatione th y sa y e Family",o familyth fma e oe th f on n r i upon,2o d an Scotlandrelationn i Land;e d th , an to fundamentall o s , tribaa y l country, wher e predominanth e t influences have consistently been Tribality and Inheritance,3 the feudal system was immensely popular, took root as a means of consolidating and preserving the earlier clannish institutions,4 e clan-systeth d an m itself was s modera , n historian recognisew no s t no , only closely intermingled with feudalism, but that clan-system was "feudal in the strictly historical sense".5 1 Stavanger Museums Aarshefle, 1016. -

Screening the Male: Exploring Masculinities in Hollywood Cinema I

SCREENING THE MALE Exploring masculinities in Hollywood cinema Edited by Steven Cohan and Ina Rae Hark London and New York First published 1993 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2002. Disclaimer: For copyright reasons, some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 © 1993 Routledge, collection as a whole Individual chapters © 1993 respective authors All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Screening the Male: Exploring Masculinities in Hollywood Cinema I. Cohan, Steven II. Hark, Ina Rae 791.4309 Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data Screening the male: exploring masculinities in Hollywood cinema/edited by Steven Cohan and Ina Rae Hark. p. cm. 1. Men in motion pictures. 2. Sex in motion pictures. I. Cohan, Steven. II. Hark, Ina Rae. PN1995.9.M46S36 1993 791.43´652041–dc20 92–5815 ISBN 0–415–07758–3 (hbk) ISBN 0–415–07759–1 (pbk) ISBN 0–203–14221–7 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0–203–22072–2 (Glassbook Format) 8 ANIMALS OR ROMANS Looking at masculinity in Spartacus Ina Rae Hark When Laura Mulvey’s ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ detailed how the cinematic apparatus and the conditions of cinema spectatorship invariably place woman as an object of the desiring male gaze, required to present herself as spectacle, its argument did not necessarily exclude the possibility that the apparatus could similarly objectify men who symbolically if not biologically lacked the signifying phallus. -

High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad

High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad An extract from the Irish Sport Horse Studbook Stallion Book The Irish Sport Horse Studbook is maintained by Horse Sport Ireland and the Northern Ireland Horse Board Horse Sport Ireland First Floor, Beech House, Millennium Park, Osberstown, Naas, Co. Kildare, Ireland Telephone: 045 850800. Int: +353 45 850800 Fax: 045 850850. Int: +353 45 850850 Email: [email protected] Website: www.horsesportireland.ie Northern Ireland Horse Board Office Suite, Meadows Equestrian Centre Embankment Road, Lurgan Co. Armagh, BT66 6NE, Northern Ireland Telephone: 028 38 343355 Fax: 028 38 325332 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nihorseboard.org Copyright © Horse Sport Ireland 2015 HIGH PERFORMANCE STALLIONS STANDING ABROAD INDEX OF APPROVED STALLIONS BY BREED HIGH PERFORMANCE RECOGNISED FOREIGN BREED STALLIONS & STALLIONS STALLIONS STANDING ABROAD & ACANTUS GK....................................4 APPROVED THROUGH AI ACTION BREAKER.............................4 BALLOON [GBR] .............................10 KROONGRAAF............................... 62 AIR JORDAN Z.................................. 5 CANABIS Z......................................18 LAGON DE L'ABBAYE..................... 63 ALLIGATOR FONTAINE..................... 6 CANTURO.......................................19 LANDJUWEEL ST. HUBERT ............ 64 AMARETTO DARCO ......................... 7 CASALL LA SILLA.............................22 LARINO.......................................... 66 -

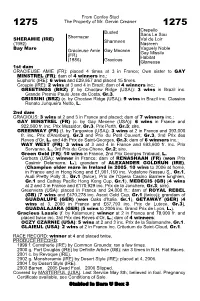

From Confey Stud the Property of Mr. Gervin Creaner Busted

From Confey Stud 1275 The Property of Mr. Gervin Creaner 1275 Crepello Busted Sans Le Sou Shernazar Val de Loir SHERAMIE (IRE) Sharmeen (1992) Nasreen Bay Mare Vaguely Noble Gracieuse Amie Gay Mecene Gay Missile (FR) Habitat (1986) Gracious Glaneuse 1st dam GRACIEUSE AMIE (FR): placed 4 times at 3 in France; Own sister to GAY MINSTREL (FR); dam of 4 winners inc.: Euphoric (IRE): 6 wins and £29,957 and placed 15 times. Groupie (IRE): 2 wins at 3 and 4 in Brazil; dam of 4 winners inc.: GREETINGS (BRZ) (f. by Choctaw Ridge (USA)): 3 wins in Brazil inc. Grande Premio Paulo Jose da Costa, Gr.3. GRISSINI (BRZ) (c. by Choctaw Ridge (USA)): 9 wins in Brazil inc. Classico Renato Junqueira Netto, L. 2nd dam GRACIOUS: 3 wins at 2 and 3 in France and placed; dam of 7 winners inc.: GAY MINSTREL (FR) (c. by Gay Mecene (USA)): 6 wins in France and 922,500 fr. inc. Prix Messidor, Gr.3, Prix Perth, Gr.3; sire. GREENWAY (FR) (f. by Targowice (USA)): 3 wins at 2 in France and 393,000 fr. inc. Prix d'Arenberg, Gr.3 and Prix du Petit Couvert, Gr.3, 2nd Prix des Reves d'Or, L. and 4th Prix de Saint-Georges, Gr.3; dam of 6 winners inc.: WAY WEST (FR): 3 wins at 3 and 4 in France and 693,600 fr. inc. Prix Servanne, L., 3rd Prix du Gros-Chene, Gr.2; sire. Green Gold (FR): 10 wins in France, 2nd Prix Georges Trabaud, L. Gerbera (USA): winner in France; dam of RENASHAAN (FR) (won Prix Casimir Delamarre, L.); grandam of ALEXANDER GOLDRUN (IRE), (Champion older mare in Ireland in 2005, 10 wins to 2006 at home, in France and in Hong Kong and £1,901,150 inc. -

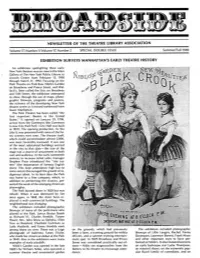

Broadside Read- a Brief Chronology of Major Events in Trous Failure

NEWSLETTER OF THE THEATRE LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Volume 17, Number 1/Volume 17, Number 2 SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE Summer/Fa111989 EXHIBITION SURVEYS MANHATTAN'S EARLY THEATRE HISTORY L An exhibition spotlighting three early New York theatres was on view in the Main I Gallery of The New York Public Library at Lincoln Center from February 13, 1990 through March 31, 1990. Focusing on the Park Theatre on Park Row, Niblo's Garden on Broadway and Prince Street, and Wal- lack's, later called the Star, on Broadway and 13th Street, the exhibition attempted to show, through the use of maps, photo- graphic blowups, programs and posters, the richness of the developing New York theatre scene as it moved northward from lower Manhattan. The Park Theatre has been called "the first important theatre in the United States." It opened on January 29, 1798, across from the Commons (the Commons is now City Hall Park-City Hall was built in 1811). The opening production, As You Like It, was presented with some of the fin- est scenery ever seen. The theatre itself, which could accommodate almost 2,000, was most favorably reviewed. It was one of the most substantial buildings erected in the city to that date- the size of the stage was a source of amazement to both cast and audience. In the early nineteenth century, to increase ticket sales, manager Stephen Price introduced the "star sys- tem" (the importation of famous English stars). This kept attendance high but to some extent discouraged the growth of in- digenous talent. In its later days the Park was home to a fine company, which, in addition to performing the classics, pre- sented the work of the emerging American playwrights. -

Land Under Pressure: the Value of Irish Land in a Period of Rapid Population Growth, 1730–1844*

Land under pressure: The value of Irish land in a period of rapid population growth, 1730–1844* land under pressure by Peter M. Solar and Luc Hens Abstract This paper uses information on almost 5000 leases to arrive at estimates for the trends in current land values in County Armagh from 1730 to 1844. The estimates control for the length of the lease, the holding size, and the quality of land in the townland where the property was located, the last relying on information from the General Valuation of Ireland. They show growth in nominal rents up to the early 1770s, a plateau in the 1770s, 1780s and 1790s, an increase to the early 1810s, followed by a fall to the early 1820s and another plateau thereafter, stretching until the famine of the late 1840s. Taken together with information on wage and price trends, the new estimates show little change in real rents and negative total factor productivity growth from the 1780s to the 1830s. The Irish economy in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was predominantly agricultural. In 1841, 53 per cent of the labour force worked on the land, and in the early eighteenth century the share was probably higher.1 The timing and direction of change in the intervening years are a matter of dispute, which is unlikely ever to be resolved fully in the absence of sufficiently reliable statistical information.2 Ireland was also experiencing one of the highest population growth rates in Europe: from the early 1750s until the 1820s upwards of 1.4 per cent per annum.3 The natural rate of population growth remained relatively high into the 1830s and early 1840s, with the actual rate slowing only with the beginnings of mass emigration. -

ALL the PRETTY HORSES.Hwp

ALL THE PRETTY HORSES Cormac McCarthy Volume One The Border Trilogy Vintage International• Vintage Books A Division of Random House, Inc. • New York I THE CANDLEFLAME and the image of the candleflame caught in the pierglass twisted and righted when he entered the hall and again when he shut the door. He took off his hat and came slowly forward. The floorboards creaked under his boots. In his black suit he stood in the dark glass where the lilies leaned so palely from their waisted cutglass vase. Along the cold hallway behind him hung the portraits of forebears only dimly known to him all framed in glass and dimly lit above the narrow wainscotting. He looked down at the guttered candlestub. He pressed his thumbprint in the warm wax pooled on the oak veneer. Lastly he looked at the face so caved and drawn among the folds of funeral cloth, the yellowed moustache, the eyelids paper thin. That was not sleeping. That was not sleeping. It was dark outside and cold and no wind. In the distance a calf bawled. He stood with his hat in his hand. You never combed your hair that way in your life, he said. Inside the house there was no sound save the ticking of the mantel clock in the front room. He went out and shut the door. Dark and cold and no wind and a thin gray reef beginning along the eastern rim of the world. He walked out on the prairie and stood holding his hat like some supplicant to the darkness over them all and he stood there for a long time. -

Monmouth Boat Club Has Diamond Jubilee

For All Departments Call RED BANK REGISTER RE 6-0013 VOLUME LXXVI, NO. 49 RED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, JUNE 3, 1954 10c PER COPY SECTION ONE—PAGES 1 TO 16. Coast Guard Auxiliary to Hold Oceanic Fire Company Celebrates 75th Anniversary Monmouth Boat Club Courtesy Exams This Week-End Has Diamond Jubilee ••- NEW YORK CITY—Roar Ad- This is the diamond jubilee year miral Louis B. Olson, commander save him a g d deal of trouble if of thn Monmouth Boat club cover- of the Coast Guard's eastern area he is inspected later by a regular State Chamber ing 73 years of boating activities. and third Coast Guard district, this Federal Communications commis- Its anniversary program, the birth- week called attention to all pleas- sion official. This check is also day date being May 29, culminates ure boat.owners to the free public rendered as a "courteBy," and no Opposes Bill 9 with thin week's activities. service of the Coast Guard auxili- report Is made to F.C.C. should it The club has Issued a souvenir ary in conducting safety examina- be found that the boat owner has history and roster, 'he introductory tions of pleasure boats. not fully complied with the laws On Teacher Pay page of which carried a message "This season," he said, "presents pertaining to vessel radio stations. from Commodoro Harvey N, a. greator challenge than ever be- Each auxiliary flotilla has its Commissioner Schcnck as follows: fore. Many new boat owners are corps of qualified examiners and "Tho Monmouth Boat club's his- venturing on the waters for the will sponsor certain localities in its Isn't Arbiter, tory over the past 75 years reveals first time with little or no experi- immediate vicinity. -

WO 2012/167278 Al 6 December 2012 (06.12.2012) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2012/167278 Al 6 December 2012 (06.12.2012) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: [RU/GB]; 6 Kilwarlin Crescent, Hillsborough, Northern G01N 33/50 (2006.01) C12Q 1/68 (2006.01) Ireland BT26 6QF (GB). KENNEDY, Richard [GB/GB]; 15 Edgcumbe Gardens, Belfast, Northern Ireland BT4 2EG (21) International Application Number: (GB). DAVISON, Timothy [US/US]; 301 Washington PCT/US20 12/040805 Street, Apt. 2109, Conshohocken, PA 19428 (US). (22) International Filing Date: WINTER, Andreas [DE/DE]; Wallensteinstrasse 19, 4 June 2012 (04.06.2012) 86368 Gersthofen (DE). MCCAVIGAN, Andrena [IE/IE]; 25 Pier Rampart, Derryadd, Lurgan, County (25) Filing Language: English Armagh, BT66 6QH (IE). (26) Publication Language: English (74) Agent: NLX, F., Brent; Johnson, Marcou & Isaacs, LLC, (30) Priority Data: 317a. E. Liberty Street, Savannah, GA 31401 (US). 61/492,488 2 June 201 1 (02.06.201 1) US (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): ALMAC kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, DIAGNOSTICS LIMITED [IE/GB]; Almac House, 20 AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, Seagoe Industrial Estate, Craigavon, Northern Ireland CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, BT63 5QD (GB). DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, (72) Inventors; and KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (75) Inventors/Applicants (for US only): HARKIN, Dennis, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, Paul [IE/GB]; 195 Ballygowan Road, Dromore Co. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Geographic Names

GEOGRAPHIC NAMES CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES ? REVISED TO JANUARY, 1911 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1911 PREPARED FOR USE IN THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE BY THE UNITED STATES GEOGRAPHIC BOARD WASHINGTON, D. C, JANUARY, 1911 ) CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES. The following list of geographic names includes all decisions on spelling rendered by the United States Geographic Board to and including December 7, 1910. Adopted forms are shown by bold-face type, rejected forms by italic, and revisions of previous decisions by an asterisk (*). Aalplaus ; see Alplaus. Acoma; township, McLeod County, Minn. Abagadasset; point, Kennebec River, Saga- (Not Aconia.) dahoc County, Me. (Not Abagadusset. AQores ; see Azores. Abatan; river, southwest part of Bohol, Acquasco; see Aquaseo. discharging into Maribojoc Bay. (Not Acquia; see Aquia. Abalan nor Abalon.) Acworth; railroad station and town, Cobb Aberjona; river, IVIiddlesex County, Mass. County, Ga. (Not Ackworth.) (Not Abbajona.) Adam; island, Chesapeake Bay, Dorchester Abino; point, in Canada, near east end of County, Md. (Not Adam's nor Adams.) Lake Erie. (Not Abineau nor Albino.) Adams; creek, Chatham County, Ga. (Not Aboite; railroad station, Allen County, Adams's.) Ind. (Not Aboit.) Adams; township. Warren County, Ind. AJjoo-shehr ; see Bushire. (Not J. Q. Adams.) Abookeer; AhouJcir; see Abukir. Adam's Creek; see Cunningham. Ahou Hamad; see Abu Hamed. Adams Fall; ledge in New Haven Harbor, Fall.) Abram ; creek in Grant and Mineral Coun- Conn. (Not Adam's ties, W. Va. (Not Abraham.) Adel; see Somali. Abram; see Shimmo. Adelina; town, Calvert County, Md. (Not Abruad ; see Riad. Adalina.) Absaroka; range of mountains in and near Aderhold; ferry over Chattahoochee River, Yellowstone National Park. -

The Memoirs of AGA KHAN WORLD ENOUGH and TIME

The Memoirs of AGA KHAN WORLD ENOUGH AND TIME BY HIS HIGHNESS THE AGA KHAN, P.C., G.C.S.I., G.C.V.O., G.C.I.E. 1954 Simon and Schuster, New York Publication Information: Book Title: The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time. Contributors: Aga Khan - author. Publisher: Simon and Schuster. Place of Publication: New York. Publication Year: 1954. First Printing Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number: 54-8644 Dewey Decimal Classification Number: 92 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY H. WOLFF BOOK MFG. CO., NEW YORK, N. Y. Publication Information: Book Title: The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time. Contributors: Aga Khan - author. Publisher: Simon and Schuster. Place of Publication: New York. Publication Year: 1954. Publication Information: Book Title: The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time. Contributors: Aga Khan - author. Publisher: Simon and Schuster. Place of Publication: New York. Publication Year: 1954. CONTENTS PREFACE BY W. SOMERSET MAUGHAM Part One: CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH I A Bridge Across the Years 3 II Islam, the Religion of My Ancestors 8 III Boyhood in India 32 IV I Visit the Western World 55 Part Two: YOUNG MANHOOD V Monarchs, Diplomats and Politicians 85 VI The Edwardian Era Begins 98 VIII Czarist Russia 148 VIII The First World War161 Part Three: THE MIDDLE YEARS IX The End of the Ottoman Empire 179 X A Respite from Public Life 204 XI Foreshadowings of Self-Government in India 218 XII Policies and Personalities at the League of Nations 248 Part Four: A NEW ERA XIII The Second World War 289 XIV Post-war Years with Friends and Family 327 XV People I Have Known 336 XVI Toward the Future 347 INDEX 357 Publication Information: Book Title: The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time.