Searching for a New Foundation in the Eleventh Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Change in Eleventh-Century Armenia: the Evidence from Tarōn Tim Greenwood (University of St Andrews)

Social Change in Eleventh-Century Armenia: the evidence from Tarōn Tim Greenwood (University of St Andrews) The social history of tenth and eleventh-century Armenia has attracted little in the way of sustained research or scholarly analysis. Quite why this should be so is impossible to answer with any degree of confidence, for as shall be demonstrated below, it is not for want of contemporary sources. It may perhaps be linked to the formative phase of modern Armenian historical scholarship, in the second half of the nineteenth century, and its dominant mode of romantic nationalism. The accounts of political capitulation by Armenian kings and princes and consequent annexation of their territories by a resurgent Byzantium sat very uncomfortably with the prevailing political aspirations of the time which were validated through an imagined Armenian past centred on an independent Armenian polity and a united Armenian Church under the leadership of the Catholicos. Finding members of the Armenian elite voluntarily giving up their ancestral domains in exchange for status and territories in Byzantium did not advance the campaign for Armenian self-determination. It is also possible that the descriptions of widespread devastation suffered across many districts and regions of central and western Armenia at the hands of Seljuk forces in the eleventh century became simply too raw, too close to the lived experience and collective trauma of Armenians in these same districts at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, to warrant -

Personal Names and Denomination of Livonians in Early Written Sources

ESUKA – JEFUL 2014, 5–1: 13–26 PERSONAL NAMES AND DENOMINATION OF LIVONIANS IN EARLY WRITTEN SOURCES Enn Ernits Estonian University of Life Sciences Abstract. This paper presents the timeline of ethnonyms denoting Livonians; specifies their chronology; and analyses the names used for this ethnos and possible personal names. If we consider the dating of the event, the earliest sources mentioning Livonians are Gesta Danorum and the Tale of Bygone Years (both 10th century), but both sources present rather dubious information: in the first the battle of Bråvalla itself or the date are dubious (6th, 8th or 10th century); in the latter we cannot be sure that the member of the Rus delegation was really a Livonian. If we consider the time of recording, the earliest sources are two rune inscriptions from Sweden (11th century), and the next is the list of neighbouring peoples of the Russians from the Tale of Bygone Years (12th century). The personal names Bicco and Ger referred in Gesta Danorum, and Либи Аръфастовъ in Tale of Bygone Years are very problematic. The first certain personal name of a Livonian is *Mustakka, *Mustukka or *Mustoikka (from Finnic *musta ‘black’) written in 1040–1050s on a strip of birch bark in Novgorod. Keywords: Livs, Finnic peoples, ethnonyms, anthroponyms, onomastics DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12697/jeful.2014.5.1.01 1. Introduction This paper (1) seeks to present the timeline of ethnonyms denoting Livonians; (2) to specify their chronology; (3) and to analyse the names used for this ethnos and possible personal names. It is supple- mental to the paper by Mauno Koski on words denoting Livonians (Koski 2011). -

(19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub

US 20040245547A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2004/0245547 A1 Stipe (43) Pub. Date: Dec. 9, 2004 (54) ULTRA LOW-COST SOLID-STATE MEMORY Publication Classi?cation (75) Inventor; Barry Cushing Stipe, San Jose, CA (51) Int. Cl.7 ................................................ .. H01L 31/109 (Us) (52) US. Cl. ............................................................ .. 257/200 Correspondence Address: (57) ABSTRACT JOSEPH P. CURTIN . A three-dimensional solid-state memory is formed from a plurality of bit lines, a plurality of layers, a plurality of tree ’ structures and a plurality of plate lines. Bit lines extend in a (73) A551 nee, Hitachi Global Stora e Technolo ies ?rst direction in a ?rst plane. Each layer includes an array of g ' B V AZ Amsterdam g memory cells, such as ferroelectric or hysteretic-resistor ' " memory cells. Each tree structure corresponds to a bit line, (21) APPL NO: 10/751 740 has a trunk portion and at least one branch portion. The trunk ’ portion of each tree structure extends from a corresponding (22) Filed; Jam 5, 2004 bit line, and each tree structure corresponds to a plurality of layers. Each branch portion corresponds to at least one layer Related US, Application Data and extends from the trunk portion of a tree structure. Plate lines correspond to at least one layer and overlap the branch (63) Continuation-in-part of application No. 10/453,137, portion of each tree structure in at least one roW of tree ?led on Jun. 3, 2003, noW abandoned. structures at a plurality of intersection regions. SRIIIIII DRAM HIIIJ FLASH PROBE GUM MTJ-MRAM 3D-MHAM MATRIX ITFBRIIM GT FERAM 001 size 50F? 012 512 502 502 5F? 002 5e? 512 002 502 Minimum "1" 100m 300m 100m 30 0m 311m 100m 40 nm 400m 10 nm 100m 100m MEX. -

Toxicological Profile for Dinitrophenols, Draft for Public

DINITROPHENOLS 149 CHAPTER 8. REFERENCES Alber M, Bîhm HB, Brodesser J, et al. 1989. Determination of nitrophenols in rain and snow. Fresenius Z Anal Chem 334:540-545. http://doi.org/10.1007/BF00483573. Ames BN, Kammen HO, Yamasaki E. 1975. Hair dyes are mutagenic: identification of a variety of mutagenic ingredients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 72(6):2423-2427. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.72.6.2423. Anderson D, Styles JA. 1978. The bacterial mutation test. Six tests for carcinogenicity. Br J Cancer 37(6):924-930. http://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.1978.134. Anderson HH, Reed AC, Emerson GA. 1933. Toxicity of alpha-dinitrophenol. Report of case. J Am Med Assoc 101(14):552-560. http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1933.02740390011003. Anderson BE, Zeiger E, Shelby MD, et al. 1990. Chromosome aberration and sister chromatid exchange test results with 42 chemicals. Environ Mol Mutagen 16 Suppl 18:55-137. http://doi.org/10.1002/em.2850160505. Arnold L, Collins C, Starmer GA. 1976. Studies on the modification of renal lesions due to aspirin and oxyphenbutazone in the rat and the effects on the kidney of 2,4-dinitrophenol. Pathology 8(3):179- 184. http://doi.org/10.3109/00313027609058995. Asman WA, Jorgensen A, Bossi R, et al. 2005. Wet deposition of pesticides and nitrophenols at two sites in Denmark: Measurements and contributions from regional sources. Chemosphere 59(7):1023-1031. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.11.048. Atkinson R. 1988. Estimation of gas-phase hydroxyl radical rate constants for organic chemicals. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02335-2 - The Collapse of the Eastern Mediterranean: Climate Change and the Decline of the East, 950–1072 Ronnie Ellenblum Index More information Index Abu¯Ka¯l¯jaı ¯r 84 Argyros, Marianos, and Norman rebellion adaptive cycle, and resilience theory 16 in southern Italy 135 al-Andalus¯,ı Abraham b. Isaac, living Artz, Frederick B., decline of Islamic culture conditions in Jerusalem 187–188 108–109 al-Basa¯s¯rı ¯,ı and Iraq civil war 96–97, 99, Ashtor, Eliyahu, decline of Islamic golden 100, 102, 105 age 109 entry into Baghdad 104 Attaleiates political rivalry with caliph and chief attacks by Uzes 143 vizier 97 and Byzantine army 133 Albert of Aachen, Jerusalem’s reservoir desertion of western Anatolia 238 199–200 Avni, Gideon, decline of classical cities al-Ghaza¯l¯ı 110 169–170 240–241 al-H˙a¯kim, caliph, forced Islamization archaeological evidence from Jerusalem destruction of Christian churches 174 170–171 and Church of the Holy Sepulchre 47 ʿayya¯ru¯n, the, prosperity in periods of dearth restoration of churches and synagogues 92–93 48, 241 al-Maghara, synagogue, and 1033 Baghdad earthquake 183–184 Abbasid caliph’s deposition of Buyid al-Maqr¯zı ¯ı 97 reliability of historical evidence 27 marriage politics with Tughril Beg water levels of Khalij 51 99 al-Muʿizz, caliph 42 caliph’s negotiations with Tughril 95 al-Muqaddas¯ı coup d’état by Sunnis 90 description of Ramla 221–222 cultural change in 6–7, 115–116, 226 visits to Jerusalem 183 desertion by Jews and Christians 34, and Jerusalem’s aqueducts -

PARTS PRICE LIST L 3/1/16 Parts Multiplier Rev

RITE ENGINEERING & MFG. CORP. 5832 GARFIELD AVE. COMMERCE, CA 90040 Tel: 562-862-2135 Fax.562-861-9821 PARTS PRICE LIST L 3/1/16 Parts Multiplier Rev. 6 Boiler Serial Number required on all Parts Orders HEADPLATE GASKETS FOR ATMOSPHERIC WATER BOILERS BOILER MODELS PART NUMBER LIST PRICE 15 through 42 21W (two required) 48 through 76 & A90 33W “ 85-200 except “A” prefix 53W “ A150, A165, A180, A200 84W “ 225-500 except “A” prefix 84W “ 550, 600, A650, A700, A750 122W “ A400, A450, A500, A550, A600, 650, 700, 750 148W “ 840 through 1250 188W “ HEADPLATE GASKETS FOR POWER BURNER FIRED WATER BOILERS BOILER MODELS PART NUMBER LIST PRICE 15 through 42 21W (two required) 48 through 76 33W “ 85 through 200 except “A” prefix 53W “ A150, A165, A180, A200, 84W “ 225 through 375 84W “ 400 through 600 except A prefix,but including A650, A700,A750 122W “ A400, A450, A500, A550, A600, 650,700, 750 148W “ 840 through 1250 188W “ HEADPLATE GASKETS FOR 15 PSIG LOW PRESSURE STEAM & HIGH “E” BOILERS BOILER MODELS PART NUMBER LIST PRICE 15S through 42S 21S (two required) 48S through 76S, 48E through 76E & A90 33S “ 85S through 200S, 85E through 200E, except “A” prefix 53S “ A150 S&E, A165 S&E, A180 S&E, A200 S&E, 225 S&E 84S “ through 375 S&E and 400E, 425E, 450E, 475E, and 500E 400S through 600S except “A” prefix, but including A650S, 122S “ A700S, A750S, 550E, 600E, A650E, A700E, and A750E A400 S&E, A450 S&E, A500 S&E, A550 S&E, A600 S&E, 148S “ 650 S&E, 700 S&E, 750 S&E 840S through 1250S & 840E through 1250E 188S “ HEADPLATE GASKETS FOR 150 PSIG HIGH PRESSURE STEAM “P” BOILERS BOILER MODELS PART NUMBER LIST PRICE P9.5 through P20 P___ Gasket (2 req’d) P25 through P50 P___ Gasket “ P75 through P125 P___ Gasket “ P150 through P250 (Specify front or rear) P___ Gasket “ HEADPLATE GASKETS FOR DURAFIN “D” WATER BOILERS DESCRIPTION PART NUMBER LIST PRICE D300 through D2500 D___ Gasket (2 req’d) DA2000 through D5000 D___ Gasket “ D5500 through D7500 D___ Gasket “ D8000 through D10000 D___ Gasket “ - 1 - RITE ENGINEERING & MFG. -

The Norman Conquest

OCR SHP GCSE THE NORMAN CONQUEST NORMAN THE OCR SHP 1065–1087 GCSE THE NORMAN MICHAEL FORDHAM CONQUEST 1065–1087 MICHAEL FORDHAM The Schools History Project Set up in 1972 to bring new life to history for school students, the Schools CONTENTS History Project has been based at Leeds Trinity University since 1978. SHP continues to play an innovatory role in history education based on its six principles: ● Making history meaningful for young people ● Engaging in historical enquiry ● Developing broad and deep knowledge ● Studying the historic environment Introduction 2 ● Promoting diversity and inclusion ● Supporting rigorous and enjoyable learning Making the most of this book These principles are embedded in the resources which SHP produces in Embroidering the truth? 6 partnership with Hodder Education to support history at Key Stage 3, GCSE (SHP OCR B) and A level. The Schools History Project contributes to national debate about school history. It strives to challenge, support and inspire 1 Too good to be true? 8 teachers through its published resources, conferences and website: http:// What was Anglo-Saxon England really like in 1065? www.schoolshistoryproject.org.uk Closer look 1– Worth a thousand words The wording and sentence structure of some written sources have been adapted and simplified to make them accessible to all pupils while faithfully preserving the sense of the original. 2 ‘Lucky Bastard’? 26 The publishers thank OCR for permission to use specimen exam questions on pages [########] from OCR’s GCSE (9–1) History B (Schools What made William a conqueror in 1066? History Project) © OCR 2016. OCR have neither seen nor commented upon Closer look 2 – Who says so? any model answers or exam guidance related to these questions. -

A Historiography of Chastity in the Marriage of Edith of Wessex and Edward the Confessor Maren Hagman Macalester College

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College History Honors Projects History Department 2011 A Historiography of Chastity in the Marriage of Edith of Wessex and Edward the Confessor Maren Hagman Macalester College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/history_honors Recommended Citation Hagman, Maren, "A Historiography of Chastity in the Marriage of Edith of Wessex and Edward the Confessor" (2011). History Honors Projects. Paper 12. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/history_honors/12 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the History Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Honors Project Macalester College Spring 201 1 Title: A Historiography of Chastity in the Marriage of Edith of Wessex and Edward the Confessor Author: Maren Hagman A Historiography of Chastity in the Marriage of Edith of Wessex and Edward the Confessor Maren Hagman History Department Professor Andrea Cremer 5/2/20 1 1 Table of Contents Acknolwedgements 3 Introduction 4-7 Methodological and Theoretical Framework 7-14 The Reign of Edward the Confessor 14-16 Part 1 Chapter 1: The Intersection of Politics and Gender in the 11th-13thcentury 17-32 Sources The Political Landscape of 11 "- 1 3" Century England 17-19 11 th- 13th Century Sources 19-23 Political Dialogues 23-32 Chapter 2: The Intersection -

Timetable 0T9NAAT

Cardiff Airport - Cardiff Service T9 (TCAT009) Bank Holiday Mondays (Inbound) Timetable valid from 7th October 2019 until further notice Operator: NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT Cardiff Airport (Terminal) 0010 0450 0510 0530 0550 0610 0630 0650 0710 0730 0750 0810 0830 0850 0910 0930 0950 1010 1030 Copthorne Hotel (Rhur Cross, Port Road) 0022s 0502s 0522s 0542s 0602s 0622s 0642s 0702s 0722s 0742s 0802s 0822s 0842s 0902s 0922s 0942s 1002s 1022s 1042s Cardiff Bay (Red Dragon Centre) 0040s 0520s 0540s 0600s 0620s 0640s 0700s 0720s 0740s 0800s 0820s 0840s 0900s 0920s 0940s 1000s 1020s 1040s 1100s Cardiff City Centre (Canal St) (Arr) 0045s 0525s 0545s 0605s 0625s 0645s 0705s 0725s 0745s 0805s 0825s 0845s 0905s 0925s 0945s 1005s 1025s 1045s 1105s Cardiff City Centre (Canal St) (Dep) -- 0530s 0550s 0610s 0630s 0650s 0710s 0730s 0750s 0810s 0830s 0850s 0910s 0930s 0950s 1010s 1030s 1050s 1110s Cardiff Centrail Rail Station -- 0531s 0551s 0611s 0631s 0651s 0711s 0731s 0751s 0811s 0831s 0851s 0911s 0931s 0951s 1011s 1031s 1051s 1111s Operator: NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT NADT Cardiff Airport (Terminal) 1050 1110 1130 1150 1210 1230 1250 1310 1330 1350 1410 1430 1450 1510 1530 1550 1610 1630 1650 Copthorne Hotel (Rhur Cross, Port Road) 1102s 1122s 1142s 1202s 1222s 1242s 1302s 1322s 1342s 1402s 1422s 1442s 1502s 1522s 1542s 1602s 1622s 1642s 1702s Cardiff Bay (Red Dragon Centre) 1120s 1140s 1200s 1220s 1240s 1300s 1320s 1340s -

The Pacx Type of Edward the Confessor

THE PACX TYPE OF EDWARD THE CONFESSOR HUGH PAGAN Introduction THE E version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that Harthacnut died at Lambeth on 8 June 1042 and that ‘before he was buried, all the people chose Edward [the Confessor] as king, in London’.1 Although it was not until Easter in the following year, 3 April 1043, that Edward the Confessor’s coronation took place, it is clear that Edward’s rule over the English kingdom was universally recognized from the summer of 1042 onwards, and historians of the English coinage have felt it appropriate to assign the start of his fi rst substantive coinage type to a date at some point during the second half of 1042. The identity of the type in question was vigorously debated by numismatic scholars during the fi rst half of the twentieth century, but evidence set out by the late Peter Seaby in an authoritative paper in the British Numismatic Journal demonstrated that Edward’s initial substantive type was PACX (BMC type iv), with the king’s left-facing profi le bust and sceptre on the obverse, and a cross design on the reverse incorporating the letters P, A, C and X in the cross’s successive quarters.2 The duration of PACX is not calculable on any proper evidential basis, but it has long been a working hypothesis among numismatists that the time span for each coin type struck between the death of Cnut in 1035 and the early 1050s is likely to have been around two years.3 On that assumption, PACX will have given way to its successor type, Radiate/Small Cross, before the end of 1044, and there is nothing in the detailed numismatic evidence presented below that is incompatible with a time span of this order. -

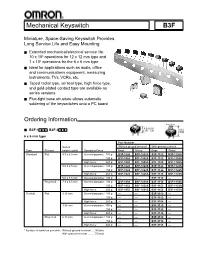

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F Miniature, Space-Saving Keyswitch Provides Long Service Life and Easy Mounting ■ Extended mechanical/electrical service life: 10 x 106 operations for 12 x 12 mm type and 1 x 106 operations for the 6 x 6 mm type ■ Ideal for applications such as audio, office and communications equipment, measuring instruments, TVs, VCRs, etc. ■ Taped radial type, vertical type, high force type, and gold-plated contact type are available as series versions ■ Flux-tight base structure allows automatic soldering of the keyswitches onto a PC board Ordering Information Flat Projected ■ B3F-1■■■, B3F-3■■■ 6 x 6 mm type Part Number Switch Without ground terminal With ground terminal Type Plunger height x pitch Operating Force Bags Sticks* Bags Sticks* Standard Flat 4.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1000 B3F-1000S B3F-1100 B3F-1100S 150 g B3F-1002 B3F-1002S B3F-1102 B3F-1102S High-force: 260 g B3F-1005 B3F-1005S B3F-1105 B3F-1105S 5.0 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1020 B3F-1020S B3F-1120 B3F-1120S 150 g B3F-1022 B3F-1022S B3F-1122 B3F-1122S High-force: 260 g B3F-1025 B3F-1025S B3F-1125 B3F-1125S 5.0 x 7.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-1110 — Projected 7.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1050 B3F-1050S B3F-1150 B3F-1150S 150 g B3F-1052 B3F-1052S B3F-1152 B3F-1152S High-force: 260 g B3F-1055 B3F-1055S B3F-1155 B3F-1155S Vertical Flat 3.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3100 — 150 g — — B3F-3102 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3105 — 3.85 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3120 — 150 g — — B3F-3122 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3125 — Projected 6.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3150 — 150 g — — B3F-3152 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3155 — * Number of switches per stick: Without ground terminal ... -

For Aearo Company Pleats Plustm 1054 and 1054S Surgical N95 Respirators

Abbreviated 510(K) For Aearo Company Pleats PlusTM 1054 and 1054S Surgical N95 Respirators II 510(k) Summary 3EC - 1 ZOG6 Company Name and Address Contact Person Aearo Company Ann Phillips 90 Mechanic Street Quality Assurance Manager Southbridge, MA 01550 Telephone 508-764-5713 Fax 508-764-5242 E-Mail ann phillips5aearo.com Manufacturing Facility Handan Hengyong Protective & Clean Products Co., LTD. Jiankang East Street Yongnian County High-Tech Development Area Hebei province, P.R. China Date Prepared September 29, 2006 Device Name Trade Name - Pleats Plus N95 Respirator 1054 and 1054S Common Name - Surgical Mask or Surgical N95 Respirator Classification CFR Section - 21 CFR 878.4040 Device Class - Class II Product Code - MSH - Surgical N95 Respirator Device Description These masks are pleated, 3-ply masks, with a center layer of polypropylene meltblown material sandwiched by inner and outer layers of nonwoven material. The mask has 2 braided synthetic elastic headbands and a flexible wire tie nosepiece that allows the respirator to form to the bridge of the wearers nose. No fiberglass media is used in this product. Intended Use Pleats Plus is intended for single use by operating room personnel or general health care workers for protection against microscopic organisms, body fluids and particulates. This would include use as a procedure mask, isolation mask or dental face mask. Aearo Company 510(k) 9/29/06 Page 3 Abbreviated 510(K) k,663&175 For Aearo Company Pleats PIusTM Surgical N95 Respirators 3 II 510(k)Summary (cont.) Pleats Plus N95 1054 and 1054S Respirators are manufactured to the same specifications as Pleats Plus 1050 which have been used in the industrial setting for over 5 years.