Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACTION STATIONS! HMCS SACKVILLE - CANADA’S NAVAL MEMORIAL MAGAZINE VOLUME 34 - ISSUE 2 SUMMER 2015 Volume 34 - Issue 2 Summer 2015

ACTION STATIONS! HMCS SACKVILLE - CANADA’S NAVAL MEMORIAL MAGAZINE VOLUME 34 - ISSUE 2 SUMMER 2015 Volume 34 - Issue 2 Summer 2015 Editor: LCdr ret’d Pat Jessup [email protected] Action Stations! can be emailed to you and in full colour approximately 2 weeks before it will arrive Layout & Design: Tym Deal of Deal’s Graphic Design in your mailbox. If you would perfer electronic Editorial Committee: copy instead of the printed magazine, let us know. Cdr ret’d Len Canfi eld - Public Affairs LCdr ret’d Doug Thomas - Executive Director Debbie Findlay - Financial Offi cer IN THIS ISSUE: Editorial Associates: Diana Hennessy From the Executive 3 Capt (N) ret’d Bernie Derible The Chair’s Report David MacLean The Captain’s Cabin Lt(N) Blaine Carter Executive Director Report LCdr ret’d Dan Matte Richard Krehbiel Major Peter Holmes Crossed The Bar 6 Photographers: Lt(N) ret’d Ian Urquhart Cdr ret’d Bill Gard Castle Archdale Operations 9 Sandy McClearn, Smugmug: http://smcclearn.smugmug.com/ HMCS SACKVILLE 70th Anniversary of BOA events 13 PO Box 99000 Station Forces in Halifax Halifax, NS B3K 5X5 Summer phone number downtown berth: 902-429-2132 Winter phone in the Dockyard: 902-427-2837 HMCS Max Bernays 20 FOLLOW US ONLINE: Battle of the Atlantic Place 21 HMSCSACKVILLE1 Roe Skillins National Story 22 http://www.canadasnavalmemorial.ca/ HMCS St. Croix Remembered 23 OUR COVER: In April 1944, HMCS Tren- tonian joined the East Coast Membership Update 25 fi shing fl eet, when her skipper Lieutenant William Harrison ordered a single depth charge Mail Bag 26 fi red while crossing the Grand Banks. -

The Canadian Cadet Movement and the Boy Scouts of Canada in the Twentieth Century

“No Mere Child’s Play”: The Canadian Cadet Movement and the Boy Scouts of Canada in the Twentieth Century by Kevin Woodger A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Kevin Woodger 2020 “No Mere Child’s Play”: The Canadian Cadet Movement and the Boy Scouts of Canada in the Twentieth Century Kevin Woodger Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto Abstract This dissertation examines the Canadian Cadet Movement and Boy Scouts Association of Canada, seeking to put Canada’s two largest uniformed youth movements for boys into sustained conversation. It does this in order to analyse the ways in which both movements sought to form masculine national and imperial subjects from their adolescent members. Between the end of the First World War and the late 1960s, the Cadets and Scouts shared a number of ideals that formed the basis of their similar, yet distinct, youth training programs. These ideals included loyalty and service, including military service, to the nation and Empire. The men that scouts and cadets were to grow up to become, as far as their adult leaders envisioned, would be disciplined and law-abiding citizens and workers, who would willingly and happily accept their place in Canadian society. However, these adult-led movements were not always successful in their shared mission of turning boys into their ideal-type of men. The active participation and complicity of their teenaged members, as peer leaders, disciplinary subjects, and as recipients of youth training, was central to their success. -

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook BA Hons (Trent), War Studies (RMC) This thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences UNSW@ADFA 2005 Acknowledgements Sir Winston Churchill described the act of writing a book as to surviving a long and debilitating illness. As with all illnesses, the afflicted are forced to rely heavily on many to see them through their suffering. Thanks must go to my joint supervisors, Dr. Jeffrey Grey and Dr. Steve Harris. Dr. Grey agreed to supervise the thesis having only met me briefly at a conference. With the unenviable task of working with a student more than 10,000 kilometres away, he was harassed by far too many lengthy emails emanating from Canada. He allowed me to carve out the thesis topic and research with little constraints, but eventually reined me in and helped tighten and cut down the thesis to an acceptable length. Closer to home, Dr. Harris has offered significant support over several years, leading back to my first book, to which he provided careful editorial and historical advice. He has supported a host of other historians over the last two decades, and is the finest public historian working in Canada. His expertise at balancing the trials of writing official history and managing ongoing crises at the Directorate of History and Heritage are a model for other historians in public institutions, and he took this dissertation on as one more burden. I am a far better historian for having known him. -

The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-39

THE POLICY OF NEGLECT: THE CANADIAN MILITIA IN THE INTERWAR YEARS, 1919-39 ___________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ___________________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY __________________________________________________________ by Britton Wade MacDonald January, 2009 iii © Copyright 2008 by Britton W. MacDonald iv ABSTRACT The Policy of Neglect: The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-1939 Britton W. MacDonald Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2008 Dr. Gregory J. W. Urwin The Canadian Militia, since its beginning, has been underfunded and under-supported by the government, no matter which political party was in power. This trend continued throughout the interwar years of 1919 to 1939. During these years, the Militia’s members had to improvise a great deal of the time in their efforts to attain military effectiveness. This included much of their training, which they often funded with their own pay. They created their own training apparatuses, such as mock tanks, so that their preparations had a hint of realism. Officers designed interesting and unique exercises to challenge their personnel. All these actions helped create esprit de corps in the Militia, particularly the half composed of citizen soldiers, the Non- Permanent Active Militia. The regulars, the Permanent Active Militia (or Permanent Force), also relied on their own efforts to improve themselves as soldiers. They found intellectual nourishment in an excellent service journal, the Canadian Defence Quarterly, and British schools. The Militia learned to endure in these years because of all the trials its members faced. The interwar years are important for their impact on how the Canadian Army (as it was known after 1940) would fight the Second World War. -

Canadian Veterans and the Aftermath of the Great War

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-7-2016 12:00 AM And the Men Returned: Canadian Veterans and the Aftermath of the Great War Jonathan Scotland The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Robert Wardhaugh The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Jonathan Scotland 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Cultural History Commons, Military History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Scotland, Jonathan, "And the Men Returned: Canadian Veterans and the Aftermath of the Great War" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3662. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3662 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract The Great War was a formative event for men who came of age between 1914 and 1918. They believed the experience forged them into a distinct generation. This collective identification more than shaped a sense of self; it influenced understanding of the conflict’s meaning. Canadian historians, however, have overlooked the war’s generational impact, partly because they reject notions of a disillusioned Lost Generation. Unlike European or American youths, it is argued that Canadian veterans did not suffer postwar disillusionment. Rather, they embraced the war alongside a renewed Canadian nationalism. -

Yankees Who Fought for the Maple Leaf: a History of the American Citizens

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 12-1-1997 Yankees who fought for the maple leaf: A history of the American citizens who enlisted voluntarily and served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force before the United States of America entered the First World War, 1914-1917 T J. Harris University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Harris, T J., "Yankees who fought for the maple leaf: A history of the American citizens who enlisted voluntarily and served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force before the United States of America entered the First World War, 1914-1917" (1997). Student Work. 364. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/364 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Yankees Who Fought For The Maple Leaf’ A History of the American Citizens Who Enlisted Voluntarily and Served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force Before the United States of America Entered the First World War, 1914-1917. A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts University of Nebraska at Omaha by T. J. Harris December 1997 UMI Number: EP73002 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Les Canadiens Franã§Ais Et Le Bilinguisme Dans Les Forces Armã

SERVICE HISTORIQUE DE LA DÉFENSE NATIONALE COLLECTION D’HISTOIRE SOCIO-MILITAIRE N° 1 Jean-Pierre Gagnon, Le 22e bataillon (canadien-français) 1914- 1919: étude socio-militaire. N° 2 Jean Pariseau et Serge Bernier, Les Canadiens français et le bilinguisme dans les Forces armées canadiennes, Tome I1763- 1969: Le spectre d’une armée bicéphale. à paraître N° 3 Armand Letellier, Réforme linguistique à la Défense nationale: la mise en marche des programmes de bilinguisme, 1967-1977. N° 4 Jean Pariseau et Serge Bernier, Les Canadiens français et le bilinguisme dans les Forces armées canadiennes, Tome II1969- 1983: Langues officielles: la volonté gouvernementale et la réponse du ministère de la Défense nationale. Hors collection Mémoires du général Jean V. Allard. (collaboration spéciale de Serge Bernier), Boucherville, Les Éditions de Mortagne, 1985. René Morin, Les écoles pour les enfants de militaires canadiens, 1921-1983, Ottawa, QGDN, Service historique, 1986. Ministre des Approvisionnements et Services Canada 1987 En vente au Canada par l’entremise des Librairies associées et autres libraires ou par la poste auprès du Centre d’édition du gouvernement du Canada Approvisionnements et Services Canada Ottawa (Canada) K I A OS9 No de catalogue 063-2/2F au Canada: $24.95 ISBN 0-660-92065-4 à l’étranger: $24.95 Prix sujet à changement sans préavis Tous droits réservés. On ne peut reproduire aucune partie du présent ouvrage, sous quelque forme ou par quelque procédé que ce suit (électronique, mécanique, photo- graphique) ni en faire un enregistrement sur support magnétique ou autre pour fins de dépistage ou après diffusion. sans autorisation écrite préalable des Services d’édition. -

Macdonald and the Catholic Vote in the 1891 Election

CCHA Study Sessions, 41(1974), 33-52 “This saving remnant”: Macdonald and the Catholic Vote in the 1891 Election by J.R. MILLER Department of History, University of Saskatchewan If there was one thing opponents and followers alike conceded S ir John Macdonald, it was the Tory leader’s ability to attract and retain the support of disparate elements of Canadian society, whether manufacturers and artisans, farmers and urbanites, or P rotestants and Catholics. Macdonald’s mastery of religious and cultural discord was graphically illustrated in a cartoon in the humourous magazine, Grip, in 1885. The artist, J.W. Bengough, portrayed the Old Chieftain as a circus trick rider with one foot on the saddle o f each of two horses which faced in different directions. On his shoulders perched a demonic-looking urchin, obviously meant to be the Métis leader who had sparked the conflict in the Northwest a short time before. The horses were labelled “ English Influence” and “ French Influence” respectively; and the caricature bore the label “ A Riel Ugly Position.”1 As the cartoon suggested, by the later 1880s worried followers of the Tory wizard were beginning to fear that the old man was losing his grip on the affection of Catholics. Some modern analysts go so far as to suggest that, as a result of the Riel, Jesuits’ Estates, and Manitoba Schools issues, Macdonald lost the Catholic vote and paved the way for the eventual disintegration of the Conservative Party in the 1890s.2 The persistent dominance of the Liberal Party, with its base in Quebec and with strong support among Catholics throughout the country, through the twentieth century, is in large part the result of Macdonald’s failure to hold on to the Catholic vote in the last years of his career. -

THE LETHBRIDGE NEWS. Tfkflr

\> THE LETHBRIDGE NEWS. VOL. XV. LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, N. W. T., THURSDAY, JUNE 14, 1900. NO. 29 MUSIC. WAR NEWS- TESTIMONIAL TOMB. MAGRATH. RS. MEALS, Teacher of Music. A very HUDSON'S BAY The committee in charge of the I MUST HAVE M good Nordheimer Piano for sale cheap. LONDON, June 11,—Gen. Forrestier- Magrath testimonial on Monday even- Walker reports that in the disaster to iug waited on Mr. Magrath at his resi COMPANY the British troops on June 7 at Roode- dence and presented him with a hand THAT Min Hotel Border Slop. val, where tbe Boers cut Lord Roberts' some Sterling silver, gold lined Orange CO-OP. line of communications, the fourth Bowl on the front of which was the r'ASHIONAKLE HAIR-CUTTINU battalion of the Derbyshire regiment following inscription : "To C. A. Ma AND EASY SUA VIM;. were all killed, wounded or made pris grath, from the Electors of the Leth bridge District, in recognition of his Picture Framed oners ^except six enlisted men, Two JAMBS HALL, * Prop. officers and 15 men were killed and five services as their first representative in officers and 72 men wounded, many of the Legislature of the Northwest Terri AT CITY RESTAURANT them severely. The Boers returned tories, 1891—1898." The bowl was a the wounded to the British. The offi very handsome piece weighing over- C. BEGIN, Prop. cers killed were, Lt.-Col. Bierd-Douglas two pounds and was procured from Mvstery! Hamilton through Mr. A. Scott, jew (j. IV. Robinson 10o.'s. Table* eupplled -.villi the beat. .IWORPORATED 1670 and Lieut. -

“Every Inch a Fighting Man”

“EVERY INCH A FIGHTING MAN:” A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE MILITARY CAREER OF A CONTROVERSIAL CANADIAN, SIR RICHARD TURNER by WILLIAM FREDERICK STEWART A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Lieutenant-General Sir Richard Ernest William Turner served Canada admirably in two wars and played an instrumental role in unifying veterans’ groups in the post-war period. His experience was unique in the Canadian Expeditionary Force; in that, it included senior command in both the combat and administrative aspects of the Canadian war effort. This thesis, based on new primary research and interpretations, revises the prevalent view of Turner. The thesis recasts five key criticisms of Turner and presents a more balanced and informed assessment of Turner. His appointments were not the result of his political affiliation but because of his courage and capability. Rather than an incompetent field commander, Turner developed from a middling combat general to an effective division commander by late 1916. -

Donald Smith Research for Honoré Jaxon: Prairie Visionary

Donald Smith research for Honoré Jaxon: Prairie Visionary. – 2.7 m of textual records; 15cm of images. Biographical Note: Donald B. Smith has co-edited such books as The New Provinces, Alberta and Saskatchewan, 1905-1980 (with the late Howard Palmer), and Centennial City: Calgary 1894-1994. His popular articles have appeared in a variety of local and national publications including Alberta History, The Beaver, the Globe and Mail, and the Calgary Herald. With Douglas Francis and Richard Jones, he published the popular two volume history text, Origins, and Destinies, and the single-volume history of Canada, titled Journeys. He has also published Calgary's Grand Story, a history of twentieth century Calgary from the vantage point of two heritage buildings in the city, the Lougheed Building and Grand Theatre, both constructed in 1911/1912. Born in Toronto in 1946, Dr. Smith was raised in Oakville, Ontario. He obtained his BA and PhD at the University of Toronto, and his M.A. at the Université Laval. He has taught Canadian History at the University of Calgary from 1974 to 2009, focusing on Canadian history in general, and on Aboriginal History, Quebec, and the Canadian North in particular. His research has primarily been in the field of Aboriginal History, combined with a strong interest in Alberta history. Scope and Content Note: The collection, 9 boxes, 2.7 meters of textual material, 15 cm of images, relates to the writing and research of Honoré Jaxon: Prairie Visionary. This book completes Donald Smith‟s “Prairie Imposters” popular history trilogy concerning three prominent figures who all pretended an Aboriginal ancestry they did not, in fact, possess – Honoré Jaxon, Grey Owl, and Long Lance. -

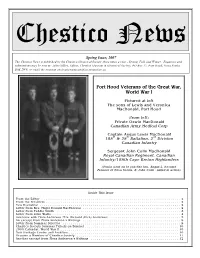

Spring 2007 Issue

Chestico News Spring Issue, 2007 The Chestico News is published by the Chestico Historical Society three times a year - Spring, Fall, and Winter. Enquiries and submissions may be sent to: John Gillies, Editor, Chestico Museum & Historical Society, PO Box 37, Port Hood, Nova Scotia, B0E 2W0, or email the museum at [email protected] Port Hood Veterans of the Great War, World War I Pictured at left The sons of Lewis and Veronica MacDonald, Port Hood (from left) Private Oswin MacDonald Canadian Army Medical Corp Captain Angus Lewis MacDonald 185th & 25th Battalion, 2nd Division Canadian Infantry Sergeant John Colin MacDonald Royal Canadian Regiment, Canadian Infantry/185th Cape Breton Highlanders (Oswin went on to practise law, Angus L. became Premier of Nova Scotia, & John Colin - killed in action) Inside This Issue From the Editor .................................................................... 2 From the President .................................................................. 2 New Executive ..................................................................... 2 Letter from Rev. Major Donald MacPherson ................................................ 2 Letter from Teddie Smith ............................................................. 3 Letter from John Watts ............................................................... 4 Interview with Flora Anderson {Mrs. Richard (Dick) Anderson} . 5 An excerpt from Flora Anderson’s Writings ................................................ 9 Letter from Summer Director .........................................................