Understanding the Structural Concept of the Design of the Winter Garden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017-12-12 Dossier De Presse Horta EN

Horta inside out: A year dedicated to this architectural genius One of the greatest architects of his generation, Victor Horta, certainly left his mark on Brussels. From the Horta House to the Hôtel Tassel and the Horta-Lambeaux Pavilion, it was about time we paid tribute to this master of Art Nouveau by dedicating a whole year to his work and creative genius. Victor Horta moved to Brussels in 1881 and went to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. His teacher, Alphonse Balat (the architect behind the Royal Greenhouses of Laeken), saw his potential and took him on as an assistant. Very quickly, he became fascinated by curves, light and steel. He soon joined the inner circle of the Masonic lodge that would launch his career. The Autrique House was built in 1893, followed closely by the wonderful Hôtel Tassel. This period was the start of a long series of showpieces which dotted Brussels with buildings with innovative spaces and bright skylights. Horta, one of the earliest instigators, heralded the modern movement of Art Nouveau architecture. The stylistic revolution represented by these works is characterised by their open plan, diffusion and transformation of light throughout the construction, the creation of a decor that brilliantly illustrates the curved lines of decoration embracing the structure of the building, the use of new materials (steel and glass), and the introduction of modern technical utilities. Through the rational use of the metallic structures, often visible or subtly dissimulated, Victor Horta conceived flexible, light and airy living areas, directly adapted to the personality of their inhabitants. -

“ I Feel Increasingly Like a Citizen of the World”

expat Spring 2013 • n°1 timeEssential lifestyle and business insights for foreign nationals in Belgium INTERVIEW “ I feel increasingly like a citizen of the world” SCOTT BEARDSLEY Senior partner, McKinsey & Company IN THIS ISSUE Property for expats Yves Saint Laurent shines in Brussels The smart investor 001_001_ExpatsTime01_cover.indd 1 11/03/13 17:41 ING_Magazine_Gosselin_Mar2013.pdf 1 11/03/2013 14:53:19 001_001_ExpatsTime01_pubs.indd 1 11/03/13 17:48 Welcome to your magazine t’s a great pleasure for me to bring you the fi rst issue of Expat Time, the quarterly business and lifestyle maga- zine for foreign nationals in Belgium. Why a new magazine for the internationally mobile Icommunity in Belgium? Belgium already has several good English-language magazines for this demographic. However, from listening to our clients, we have realised that there is a keen interest in business and lifestyle matters that aren’t covered by the current expat magazine offer. Subjects like estate planning, pensions, property, work culture, starting a business in Belgium, investments and taxation are of real interest to you, but they don’t seem to be answered in full by any of the current English-language expat magazines. That is a long sentence full of dry business and investment content. It is, however, our commitment to bring a fresh and lively perspective to these subjects with the help of respected experts in the various fi elds. We will look not only at topics related to business in Belgium. The other half of Expat Time will be much lighter and devoted to lifestyle in Belgium: insights from expats in Belgium, a regular light-hearted feature on fundamental changes in the world, arts and culture, events and more. -

Branding Brussels Musically: Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism in the Interwar Years

BRANDING BRUSSELS MUSICALLY: COSMOPOLITANISM AND NATIONALISM IN THE INTERWAR YEARS Catherine A. Hughes A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Annegret Fauser Mark Evan Bonds Valérie Dufour John L. Nádas Chérie Rivers Ndaliko © 2015 Catherine A. Hughes ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Catherine A. Hughes: Branding Brussels Musically: Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism in the Interwar Years (Under the direction of Annegret Fauser) In Belgium, constructions of musical life in Brussels between the World Wars varied widely: some viewed the city as a major musical center, and others framed the city as a peripheral space to its larger neighbors. Both views, however, based the city’s identity on an intense interest in new foreign music, with works by Belgian composers taking a secondary importance. This modern and cosmopolitan concept of cultural achievement offered an alternative to the more traditional model of national identity as being built solely on creations by native artists sharing local traditions. Such a model eluded a country with competing ethnic groups: the Francophone Walloons in the south and the Flemish in the north. Openness to a wide variety of music became a hallmark of the capital’s cultural identity. As a result, the forces of Belgian cultural identity, patriotism, internationalism, interest in foreign culture, and conflicting views of modern music complicated the construction of Belgian cultural identity through music. By focusing on the work of the four central people in the network of organizers, patrons, and performers that sustained the art music culture in the Belgian capital, this dissertation challenges assumptions about construction of musical culture. -

Heritage Days 14 & 15 Sept

HERITAGE DAYS 14 & 15 SEPT. 2019 A PLACE FOR ART 2 ⁄ HERITAGE DAYS Info Featured pictograms Organisation of Heritage Days in Brussels-Capital Region: Urban.brussels (Regional Public Service Brussels Urbanism and Heritage) Clock Opening hours and Department of Cultural Heritage dates Arcadia – Mont des Arts/Kunstberg 10-13 – 1000 Brussels Telephone helpline open on 14 and 15 September from 10h00 to 17h00: Map-marker-alt Place of activity 02/432.85.13 – www.heritagedays.brussels – [email protected] or starting point #jdpomd – Bruxelles Patrimoines – Erfgoed Brussel The times given for buildings are opening and closing times. The organisers M Metro lines and stops reserve the right to close doors earlier in case of large crowds in order to finish at the planned time. Specific measures may be taken by those in charge of the sites. T Trams Smoking is prohibited during tours and the managers of certain sites may also prohibit the taking of photographs. To facilitate entry, you are asked to not B Busses bring rucksacks or large bags. “Listed” at the end of notices indicates the date on which the property described info-circle Important was listed or registered on the list of protected buildings or sites. information The coordinates indicated in bold beside addresses refer to a map of the Region. A free copy of this map can be requested by writing to the Department sign-language Guided tours in sign of Cultural Heritage. language Please note that advance bookings are essential for certain tours (mention indicated below the notice). This measure has been implemented for the sole Projects “Heritage purpose of accommodating the public under the best possible conditions and that’s us!” ensuring that there are sufficient guides available. -

Heritage Days Recycling of Styles 17 & 18 Sept

HERITAGE DAYS RECYCLING OF STYLES 17 & 18 SEPT. 2016 Info Featured pictograms Organisation of Heritage Days in Brussels-Capital Region: Regional Public Service of Brussels/Brussels Urban Development Opening hours and dates Department of Monuments and Sites a CCN – Rue du Progrès/Vooruitgangsstraat 80 – 1035 Brussels M Metro lines and stops Telephone helpline open on 17 and 18 September from 10h00 to 17h00: 02/204.17.69 – Fax: 02/204.15.22 – www.heritagedaysbrussels.be T Trams [email protected] – #jdpomd – Bruxelles Patrimoines – Erfgoed Brussel The times given for buildings are opening and closing times. The organisers B Bus reserve the right to close doors earlier in case of large crowds in order to finish at the planned time. Specific measures may be taken by those in charge of the sites. g Walking Tour/Activity Smoking is prohibited during tours and the managers of certain sites may also prohibit the taking of photographs. To facilitate entry, you are asked to not Exhibition/Conference bring rucksacks or large bags. h “Listed” at the end of notices indicates the date on which the property described Bicycle Tour was listed or registered on the list of protected buildings. b The coordinates indicated in bold beside addresses refer to a map of the Region. Bus Tour A free copy of this map can be requested by writing to the Department of f Monuments and Sites. Guided tour only or Please note that advance bookings are essential for certain tours (reservation i bookings are essential number indicated below the notice). This measure has been implemented for the sole purpose of accommodating the public under the best possible conditions and ensuring that there are sufficient guides available. -

N a M U R L'art Dans La Ville

NAMUR L’ART DANS LA VILLE La fresque de la Villa Balat DÉMOSTHÈNE STELLAS ÉTÉ 2020 NAMUR L’ART DANS LA VILLE Une fresque monumentale sur la Villa Balat ! C’est une fresque monumentale placée sous Ce principe de simplification cher à le signe de la simplicité et de la nature qui Balat, Démosthène a choisi de l’appliquer va fleurir cet été en bordure de Meuse à à sa peinture murale qui sera composée Jambes dans un lieu très courtisé par les d’éléments détaillés et d’autres synthéti- promeneurs… sés ou esquissés. En accord avec les pro- priétaires de la villa mosane, aujourd’hui À la mi-juillet, Démosthène Stellas, membre maison d’hôtes, l’artiste est parti de quelque du collectif namurois Drash, va se lancer chose de réaliste pour arriver à des motifs dans la création d’une grande peinture simplifiés, dans un style épuré. Il a souhai- sur le mur aveugle de la Villa Balat. Cette té intégrer la citation de Balat à la fresque peinture composée de formes végétales afin d’en faciliter la lecture. rendra hommage à l’architecte Alphonse Balat et à l’époque dans laquelle il s’ins- L’œuvre trouve également sa source crit (les prémices de l’Art nouveau). Formé d’inspiration dans les macrophotographies à l’Académie des Beaux-arts de Namur, de plantes de Karl Blossfledt, l’auteur des puis d’Anvers, Alphonse Balat fut le men- " Essentielles ", une référence dans les tor de Victor Horta et l’un des principaux écoles d’arts décoratifs. Ses motifs architectes du roi Léopold II. -

Art Nouveau in Brussels and Paris 28/30 January 2002/5 Feb. Samuel

Art Nouveau in Brussels and Paris 28/30 January 2002/5 Feb. Samuel Bing, Art Nouveau Shop, rue de Provence, Paris 1895 A. Mackmurdo, Frontispiece to “Wren’s Churches” London 1888 Aubrey Beardsley, Salome, 1893 Jan Toorop (Belgian painter), Song of the Ages, 1893 Gustave Serrurier-Bovy, Art Nouveau furniture, exs. Of 1898 and 1900 Victor Horta Hôtel Tassel (Tassel House), Brussels, 1892-95 Hôtel Solvay, Brussels 1895-1900 Hôtel van Eetveld, Brussels 1895-1901 Hôtel Horta (architect’s own house), Brussels, 1898 Maison du Peuple, Brussels 1896-99 L’Innovation (Department Store), Brussels 1901 Gare Centrale (central railroad station), Brussels, 1925 Paul Hankar Hôtel Ciamberlani, Brussels 1897 Niguet Shop, Brussels 1899 Colonial Section, Exposition, Brussels, 1897 Henri van de Velde Bloemenwerf (architect’s own house), Uccle (Brussels), 1894-95 Havana Company Shop, Berlin 1899 Office for Meier-Graefe, Paris 1898 Study at the Secession Exhibition, Munich 1899 Haby’s Hairdressing Salon, Berlin, 1901 New Buildings for the Art School, in Weimar (later the Bauhaus, Weimar) 1906 (Temporary) Theater, Werkbund Exposition, Cologne, 1914 Hector Guimard Ecole du Sacre-Coeur, Paris 1895 Castel Béranger, Paris 1894-97 Humbert Romains Concert Hall, Paris 1898 Coilliot House, Lille 1898-1900 Paris Métro Stations and signage, 1897-1904 Hôtel Guimard (architect’s own house), Paris 1911 Projects for prefabricated houses, 1922 Louis Majorelle, Victor Prouvé, Henri Sauvage and the Nancy School of Art Nouveau in Lorraine: Villa Majorelle at Nancy by Sauvage 1901-02 24 rue Liomnoios, Nancy by Weissenburger 1903-04g Quai Claude Lorraine, Nancy by André 1903 Comparisons with: Charles Garnier, Paris Opera (1861-75), Eiffel Tower Paris by Gustave Eiffel 1888-89 Alphonse Balat: Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels and Greenhouses at Laaken (1876) Concept of Einfühlung (Empathy) in relation the the design and theory of Munich art nouveau architect Auguste Endell, Elivra Photographic Studio, Munich 1897 Anatole de Baudot (pupil of Viollet-le-Duc), Lycée Lakanal, Sceaux (nr. -

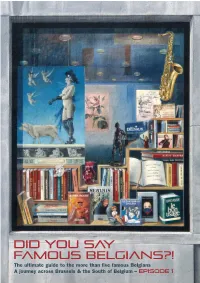

The Ultimate Guide to the More Than Five Famous Belgians a Journey

The ultimate guide to the more than five famous Belgians A journey across Brussels & the South of Belgium – Episode 1 Rue St André, Brussels © Jeanmart.eu/belgiumtheplaceto.be When a Belgian arrives in the UK for the delighted to complete in the near future first time, he or she does not necessarily (hence Episode I in the title). We Belgians expect the usual reaction of the British when are a colourful, slightly surreal people. they realise they are dealing with a Belgian: We invented a literary genre (the Belgian “You’re Belgian? Really?... Ha! Can you name strip cartoon) whose heroes are brilliant more than five famous Belgians?.” When we ambassadors of our vivid imaginations and then start enthusiastically listing some of of who we really are. So, with this Episode 1 our favourite national icons, we are again of Did you say Famous Belgians!? and, by surprised by the disbelieving looks on the presenting our national icons in the context faces of our new British friends.... and we of the places they are from, or that better usually end up being invited to the next illustrate their achievements, we hope to game of Trivial Pursuit they play with their arouse your curiosity about one of Belgium’s friends and relatives! greatest assets – apart, of course, from our beautiful unspoilt countryside and towns, We have decided to develop from what riveting lifestyle, great events, delicious food appears to be a very British joke a means and drink, and world-famous chocolate and of introducing you to our lovely homeland. beer - : our people! We hope that the booklet Belgium can boast not only really fascinating will help you to become the ultimate well- famous characters, but also genius inventors informed visitor, since.. -

Victor Horta: the Maison Tassel, the Sources of Its Development , / in Architecture, Art Nouveau Initiated a Major Is Inevitable

108 GEORGE TSIHLIAS, UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Victor Horta: The Maison Tassel, The Sources of its Development , / In architecture, Art Nouveau initiated a major is inevitable. N~IY all accounts hold some change in structural thinking, despite its mention of the man whose creative efforts relatively brief and uncertain life. It lasted for were to culminate in the first definitive some 20 years, or even less in some Western manifestation of a significant episode in European countries. Once all the rage, it came modem architectural development. Invariably, to be abandoned by its enthusiastic adherents descriptions of the Maison Tassel figure as the wild oats of youth. Its numerous prominently among their contents. The architectural exponents sought to express the product of a more personalized form of same inspiring motivation which characterized expression, the house represents the first time the applied arts. The correspondingly sinuous Horta came into his own as an architect. It linearity; the biomorphic qualities; the semi evoked the spirit of a generation obsessed naturalistic, semi-abstract elements - both with change, novelty and progress. At the structural and decorative; all were present in same time, it designated the beginning of a its varied examples. Moreover, one had the period which would lead to world fame for the floral reference to the total forms of plants. Belgian architect who engendered it. Upon The leaves; the stalks; the roots; the blossoms; completion, the project was heralded as the these formed the epitome of the constant first declaration of a victorious modem organic expression which was the order of the movement; the first truly modernist work. -

National Museums in Belgium Felicity Bodenstein

Building National Museums in Europe 1750-2010. Conference proceedings from EuNaMus, European National Museums: Identity Politics, the Uses of the Past and the European Citizen, Bologna 28-30 April 2011. Peter Aronsson & Gabriella Elgenius (eds) EuNaMus Report No 1. Published by Linköping University Electronic Press: http://www.ep.liu.se/ecp_home/index.en.aspx?issue=064 © The Author. National Museums in Belgium Felicity Bodenstein Summary The problematic and laboriously constructed nature of the Belgian nation is, to a large extent, reflected in the structure and distribution of Belgium’s federal/national museums. The complexity and contradictory nature of the administrative organisation of the Belgian state led one of its leading contemporary artists to comment that ‘maybe the country itself is a work of art’ (Fabre, 1998: 403). Its national museums - those which receive direct federal funding - are the result of a series of projects that founded the large cultural institutions of Brussels in the nineteenth century, decreed by the Belgian monarchy that was itself only founded in 1830. Brussels, the largely French speaking capital of the nation situated geographically in the centre of a Flemish speaking region, is since 1830 the seat of a constitutional monarchy and democratically elected parliament that governs over the two very distinct linguistic and cultural areas: the northern Dutch-speaking Flanders and southern French-speaking Wallonia. In his article on ‘What, if Anything, Is a Belgian?’, Van der Craen writes : ‘Belgium has been at the centre of a heated debate since its creation. The relatively young country has had little time to develop any nationalistic feelings in comparison to, for instance, the Netherlands or France’ (2002 : 32). -

Action Plan for Botanic Gardens in the European Union

m .c .a 'Ii Scripta Botanica Belgica 19 Action Plan for Botanic Gardens in the European Union Edited and compiled by Judith Cheney, Joaquin Navarrete Navarro and Peter Wyse Jackson for the BGCVIABG European Botanic Gardens Consortium Scripta Botanica Belgica Miscellaneous documentation edited by the National Botanic Garden of Belgium Series editor: E. Robbrecht Volume 19 edited and compiled by Judith Cheney, Joaquh Navarrete Navarro and Peter Wyse Jackson for the BGCYIABG European Botanic Gardens Consortium Volume 19 Action Plan for Botanic Gardens in the European Union CIP Royal Library Albert I, Brussels Action Plan for Botanic Gardens in the European Union/ Judith Cheney, Joaquin Navarrete Navarro and Peter Wyse Jackson (editors) - Meise: Ministry for SMEs and Agriculture, Directorate of Research and Development, National Botanic Garden of Belgium, 2000.- (ii) + 68 pp.; 26.5 cm. -(Scripta botanica Belgica; Vol. 19). ISBN 90-72619-45-5 ISSN 0779-2387 Subjects: Botany D/2000/0325/2 All photographs by Peter Wyse Jackson, unless otherwise stated. Front cover: Native plants garden at the Funchal Botanic Garden, Madeira, Portugal and (top left) Chelsea Physic Garden, London, UK (Ruth Taylor). Back cover: National Botanic Garden of Wales, UK (top); Jardin Bothico de Cdrdoba, Spain (middle); Orto Botanico, Pisa, Italy (bottom). Published in April 2000 by National Botanic Garden of Belgium for Botanic Gardens Conservation International 0 BGCI 2000 Printed in Belgium by Universa, Wetteren Acknowledgements BGCI is grateful to the many people who assisted in the preparation of this Action Plan, particularly the authors of different chapters; those who provided text for inclusion in the Plan; and those who drafted case studies or provided data, in many different forms. -

Les Boulevards Extérieurs De La Place Rogier À La Porte De

BRUXELLES, VILLE D'ART ET D'HISTOIRE BRUXELLES, VILLE D'ART ET D'HISTOIRE LES BOULEVARDS Comité de coordination Ariane Herman, Cabinet du Ministre-président Stéphane Demeter, Richard Kerremans, Manoëlle Wasseige, Service des Monuments et des Sites EXTERIEURS DE LA PLACE ROCIER À LA PORTE DE HAL Réalisation asbl C.I.D.E.P. (Centre d'information, de Documentation et d'Etude du Patrimoine) Laure Eggericx et Christine Van Quorie Remerciements Chantal Déom Christian Spapens, architecte-urbaniste LA PETITE CEINTURE DU MOYEN ÂGEÀ NOS JOURS .............................................. 2 Bruxelles fortifiée ............................................................................. 4 Bruxelles 1800 ................................................................................. 6 DU DÉMANTÈLEMENT DES FORTIFICATIONS ILLUSTRATIONS À LA CIÜATION DES BOULEVARDS EXTÉRIEURS .............. 8 H=haut; M=milieu; 8=bas; g=gauche; d=droite; c=centre Archives Générales du Royaume: 48; 7Hd. Archives de la Ville de Bruxelles: 7Hg; 7Hc; 208; 248; 28H; 30; Les portes de la ville......................................................................... 8 44H; 48H. Archives de Saint-Josse-ten-Noode: 17H. Bibliothèque Royale: 4H; 5H; 11; 14H; 22H. Le concours de 1818 ........................................................................ 1 O CI.D.E.P.: 58; 6; 8; 9; 12; 13; 148; 15; 168; l 7B; 18; 19M; l 9B; 20H; 21H; 21 m; 218; 22M; 228; 238; 24H; 25H; 258; 26; 27; 288; 29Hd; 31 H; 318; 32Bg; 328d; 33H; 338; 34H; 35H; 358; 36H; 368; 37H; 378; « Embellissement de Bruxelles», le plan de Vifquain........................... 11 38H; 39; 40H; 408; 41; 42H; 43H; 43M; 438; 448; 458; 46H; 46M; 468; 47H; 478; 48M. Institut Royal du Patrimoine Artistique: 2-3; 29Hg; 32H. Ministère des Travaux Publics: 348. Schmitz Michel: 428. LES BOULEVARDS. DE LA PLACE ROGIERÀ LA Service des Monuments et Sites: 23H; 298.