The Story of Reo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyricht, 1914, by Kanaaa Farmer Co

CopyriCht, 1914, by Kanaaa Farmer Co. Septe!Dber 12, 1014 KANSAS FARME'P 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111"1,,.1111,111111111111111111111111IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII� OIIIII1II1II1IUIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 ,IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIJIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111", � IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIUIIIIII'IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII1IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII,IIIIIIIIIIII(llll1�"111I11I11I11I11I11I11I11I11I11I1IIIIIIIII,... iii .'1111111 Brothers .soua if son' , \ il;;;; Apper iii Home:-'Ma'de Automo.bil es IIiii �ii iii iii == 'know what to in a "home-made" pie. �� You expect -- ii new a ii Let us tell what we mean when we call the Apperson iii you ii 41home-mad� automobile." ii • ii lir.t I • car, "anel Apper.ota, Americd. , ,�� A bjt',:':Etnl��" Edgar -- ·de.igned: ii / own our motor car builder.-+95%···of tlie part. made in our factory, by �� -- of ii own men-the entire car con.tructed under the per.onal mpervi.ion �i ii Brother•• ii the Apper.on == �! -- because , what into the· finished car, ii Thus we know just exactly goes �! -- we make the- ii ii ii Fenders ii Motors Steering Gears Drop Forgings �� Brake Rods and Cushions -- Transmissions Famous Apperson ii Sweet-Metal iii Axles Clutch Control Rods All ii Rear ii Parts == Radiators '. Froitt Axles �� Bra�es -

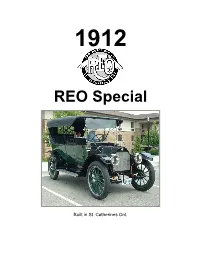

REO and the Canadian Connection

1912 REO Special Built in St. Catherines Ont. Specifications 1912 REO Body style 5 passenger touring car Engine 4 cylinder "F-Head" 30-35 horsepower Bore & Stroke: 4 inch X 4 ½ inches (10 cm X 11.5 cm) Ignition Magneto Transmission 3 speeds + reverse Clutch Multiple disk Top speed 38 miles per hour (60 k.p.h.) Wheelbase 112 inches (2.8 metres) Wheels 34 inch (85 cm) demountable rims 34 X 4 inch tires (85 cm X 10 cm) Brakes 2 wheel, on rear only 14 inch (35 cm) drums Lights Headlights - acetylene Side and rear lamps - kerosene Fuel system Gasoline, 14 gallon (60 litre) tank under right seat gravity flow system Weight 3000 pounds (1392 kg) Price $1055 (U.S. model) $1500 (Canadian model) Accessories Top, curtains, top cover, windshield, acetylene gas tank, and speedometer ... $100 Self-starter ... $25 Features Left side steering wheel center control gear shift Factories Lansing, Michigan St. Catharines, Ontario REO History National Park Service US Department of the Interior In 1885, Ransom became a partner in his father's machine shop firm, which soon became a leading manufacturer of gas-heated steam engines. Ransom developed an interest in self- propelled land vehicles, and he experimented with steam-powered vehicles in the late 1880s. In 1896 he built his first gasoline car and one year later he formed the Olds Motor Vehicle Company to manufacture them. At the same time, he took over his father's company and renamed it the Olds Gasoline Engine Works. Although Olds' engine company prospered, his motor vehicle operation did not, chiefly because of inadequate capitalization. -

Electric and Hybrid Cars SECOND EDITION This Page Intentionally Left Blank Electric and Hybrid Cars a History

Electric and Hybrid Cars SECOND EDITION This page intentionally left blank Electric and Hybrid Cars A History Second Edition CURTIS D. ANDERSON and JUDY ANDERSON McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Anderson, Curtis D. (Curtis Darrel), 1947– Electric and hybrid cars : a history / Curtis D. Anderson and Judy Anderson.—2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-3301-8 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Electric automobiles. 2. Hybrid electric cars. I. Anderson, Judy, 1946– II. Title. TL220.A53 2010 629.22'93—dc22 2010004216 British Library cataloguing data are available ©2010 Curtis D. Anderson. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: (clockwise from top left) Cutaway of hybrid vehicle (©20¡0 Scott Maxwell/LuMaxArt); ¡892 William Morrison Electric Wagon; 20¡0 Honda Insight; diagram of controller circuits of a recharging motor, ¡900 Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Je›erson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com To my family, in gratitude for making car trips such a happy time. (J.A.A.) This page intentionally left blank TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms and Initialisms ix Preface 1 Introduction: The Birth of the Automobile Industry 3 1. The Evolution of the Electric Vehicle 21 2. Politics 60 3. Environment 106 4. Technology 138 5. -

REO at the MSU Archives REO Motors Inc

REO and the Automobile Industry A Guide to the Resources in the Michigan State University Archives and Historical Collections Compiled by Ed Busch Michigan State University Archives 101 Conrad Hall East Lansing, MI (517) 355 - 2330 archives.msu.edu January 2012 Updated December 2015 The purpose of this resource guide is to familiarize visitors of the MSU Archives with some of the available resources related to the REO and other automobile company records. Note that this guide is not a comprehensive listing of all the available sources, but is intended to be a starting point from which visitors can begin their research according to their specific needs. Online versions of the finding aids for most collections listed can be accessed by clicking on the collection name. REO at the MSU Archives REO Motors Inc. was incorporated in 1904 by R. E. Olds and other investors as the R. E. Olds Company. It passed through several name changes and permutations until May 30, 1975, when Diamond REO Trucks, Inc., filed for bankruptcy. In its lifetime, the company built passenger cars and trucks, but it was best known for the latter. The company became dependent on government contracts in the 1940s and 1950s, but by 1954 continuing losses led to a takeover by a group of majority stockholders. From 1954 to 1957 the company went through a series of business crises ultimately leading to its purchase by White Motors and the formation of the Diamond REO Truck Division of White Motors in 1957. REO Motors 1. REO Motor Company Records 00036 283 Volumes, 170 cubic feet This collection consists of the business records of REO Motors, Inc. -

PARAGUAY for ARBITRATION, CHENEY GOODS TOUPHOISTER LEAGUE TOLD! 'T Ln E S Ra U T O REPORT READ “CONGRESS IS BECOMING CLUB OF

'T^ i'.' r- " ■'.r. f v" ■ ii ■ V - *: v;- . , ■■';; V - f ' ,j- ' . ‘ ’■. ■ XHB WBATHBR n b ITPRESS r u x Ftwecaat br O. S. Weatlmr Oareaa, ^ I Siait Uavcn AVERAGB DAILY CIHCDLATIOX for the month of November, 1028 Fair tonight; Friday increasing 5,237 cloadinefls.' .Member of the 'Andit Darean of ^ >-i ‘ ■'6' Clrcnlatlona (P. O. So. BIanchester,'pi>nn.>, PRICE THREE CENT’S MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY, DECEMBER 13, 1928. v oL ja n ., NO. 51. (FOURTEEN PAGES) PARAGUAY FOR CHENEY GOODS Search for Fiend’s Victim ARBITRATION, TOUPHOISTER 1 LEAGUE TOLD! ‘T lN E SrA U T O REPORT READ ! • ______ ---------- I But Note to Council Adds!Local Firm Gets Contract Judge Has Doubts as to Woman Ruler Rallies However . i i. 1 ^ , Which Raises Hopes of That Bolivia is Not In from Reo for Special Line Right to Function So Or For Selling Liquor Doctors at Bedside— Bul clined to Settle Border of Custom-Built Cars; ders New Panel— Funds letin Says Monarch Was HiGh Quality Work. of Embezzler Traced. Lansing, Mich., Dec. 13.-—Etta months. Good behavior cut this, Dispute. Miller, 48, mother of ten children, tifiie to less than a year, most of was in jail here today a'waltinG sen which was served in the Ingham Not LosinG Ground— Next Hartfdrd, Conn,, Dec. 13.— The tence of life imprsonment, while county jail. , Cheney Brothers, local silk firm, ' \ , f BULLF-TIN Grand Jury Investigating the af state-wide protest against her fate Her fourth conviction here yes have been aw’arded the contract for terday was for delivering two pints 24 Hours Will Be Crucial IVasliingtoii, Occ. -

Capital Bank Tower______Other Name ~ /Site Number Boji Tower

NPS Form 10-900 (Rev. Aug. 2002) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service 8 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES ~~ ~A~I~Wfl %~ks~~~~1{fACES REGISTRATION FORM .. - ... .. This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 1 0-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. =============================================================================== 1. N arne of Property =============================================================================== historic name _Capital Bank Tower_________________ _ other name ~ /site number _Boji Tower. ===========~=================================~================================= 2. Location =========================~===================================================== street & number _124 W. Allegan Street not for publication_N/A_ city or town _Lansing_ _ _____ vicinity _N/A_ st:2tc ___Michigan ____ code _MI_ county _Ingham code _065 zip code _ 48933 __ -

Harmony Rules Convention As the Nominations Continue

THE WEATHER NET PRESS RUN Forecast br D. S. Weather nareaab « Near Havea AVERAGE DAILY CIRCULATION for the month of May, 1028 5 , 1 4 0 iEufttum Fair tonight; Friday partly cloudy. Heaibet of t^e Andii Unrean ot Clrenlatlona PRipE THREE CENTS ,^°!!r^tJRTEEN PAGES) VOL. X U L , NO. 231, Classified^ Advertising on Page 12, MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY, JUNE 28, 1928, BANDITS TRY WISCONSIN STAGES A DEMONSTRATION <S> - - HARMONY RULES CONVENTION T O W COP WITH HAMMER lA AS THE NOMINATIONS CONTINUE Flood of Oratory Drenches Perspiring Delegates as Fa Bat Darien Policeman Hand 1 Dry And Farm Planks cuffs Them to Auto and vorite Sons Are Named— Cheers Every Time Smith s Recovers 95 Women’s / Satisfy Both Sides Name is Mentioned— Platform Agreed Upon to Satis faction of All Factions, Is latest Report. Dressed Houston, Texas, June 28.— A<|>publican Party for its failure to ] enact remedial legislation. ❖ strict law enforcement plank. In sharp contrast to the bitter <9---------- pledging the Democratic Party to tights which have rocked the Dem A BIRD’S EYE VIEW Darien, Conn., June 28.— Police Sam Houston Hall, Houston, OF THE SITUATION enforce rigidly the Eighteenth 1 ocrats in the past, the long meeting Texas, June 28.— Peace and har man Amos Anderson today battled Amendment as well as all other of the drafting cornmittee of four Houston, Texas, June 28.—;■ three colored men, arrested them, teen members was peaceful and mony, long strangers at Democratic provisions of the constitution, was | harmonious. conventions, loomed large over Sam Here is a bird’s eye view of the recovered several thousand dollars situation in the Democratic written into the platform today by j “ it was the most pleasant and Houston Hall today as the weary ■worth of wearing apparel stolen the resolutions sub-committee fol- I harmonious meeting of the kind I ve convention today. -

The URC's Contributions to Automotive Innovation

May 30, 2012 The URC’s Contributions to Automotive Innovation Prepared by: Anderson Economic Group, LLC Caroline M. Sallee, Director Alex Rosaen, Consultant Erin Grover, Senior Analyst Commissioned by: The University Research Corridor Anderson Economic Group, LLC 1555 Watertower Place, Suite 100 East Lansing, Michigan 48823 Tel: (517) 333-6984 Fax: (517) 333-7058 www.AndersonEconomicGroup.com © Anderson Economic Group, LLC, 2012 Permission to reproduce in entirety granted with proper citation. All other rights reserved. Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................... i I. Introduction and Main Findings ............................................... 1 Report Purpose ............................................................................ 1 Overview of Approach ................................................................ 1 Summary of Findings .................................................................. 2 About Anderson Economic Group .............................................. 6 II. Auto Industry Overview and Challenges ................................. 7 Brief History of the Auto Industry .............................................. 7 Current State of Michigan’s Auto Industry ............................... 10 Challenges Driving Innovation .................................................. 13 Addressing Challenges Using Innovation ................................. 14 III. The Role of the URC in Auto Industry Innovation................ 16 How Are New Automotive -

REO Motor Company Records

REO Motor Company Records http://archives.msu.edu/findaid/036.html SUMMARY INFORMATION Repository Michigan State University Archives and Historical Collections Creator Reo Motor Car Company. Title REO Motor Car Company records ID 00036 Date [inclusive] 1904-1976 Extent 170.0 Cubic feet 170 cu ft , 283 volumes HISTORICAL NOTE Both the beginning and end of the REO company occurred amid controversy. The firm was incorporated on August 16, 1904 by R.E. Olds and other investors as the R.E. Olds Company. It quickly passed through several name changes and permutations. On May 30, 1975 the firm, then known as Diamond REO Trucks, Inc., filed for bankruptcy. Ransom Eli Olds, founder of the Olds Motor Works (later the Oldsmobile Division of General Motors), was forced out of that firm in 1902. Two years later, Olds and other investors formed the R.E. Olds Co. to manufacture automobiles. Following a legal threat from the Olds Motor Works, the R.E. Olds Company's name was changed to the REO Car Company (which later became the REO Motor Car Company). On October 8, 1910 the investors also formed the REO Motor Truck Company to manufacture trucks, eventually known as "speedwagons." This firm was combined with the REO Motor Car Company on September 29, 1916. During 1919 the firm sold more trucks than cars for the first time, and continued to do so until 1936. In that year car production was halted due to losses from declining sales which were caused by the Great Depression. The firm was reorganized in 1938 as REO Motors, Inc. -

Iesiiji Z Mrafcllliliw Wfiypiillsj§G§Pil L ^SQJJC-Sgsgisgp Wbsbf 2 the M

m iBRArtV MICHIGAN STATE COLLEGE OF AGRi. AND APP. SCIENCE n Michigan Agricultural College Association Publishers a East Lansing Vol. XXIX Nov. 19, 1923 No. 9 = s I =sj§gj Hal »SB iEsiijI Z Mrafcllliliw wfiypiillSj§g§pil l ^SQJJC-sgsgisgp WBSBf 2 THE M. A. C. RECORD Hie Gold Simadmrd of Valme^ Lansing's Largest Industry The Reo Motor Car Company extends visiting alumni of M. A. C. a cordial invitation to visit its factory and watch Reo products in course of manufacture. In its 25 miles of aisles are 5968 individual machines, giv ing employment to 4,584 persons, exclusive of the office force. Of the 49 acres of land owned by the company, 34 is actually built upon; the floor space of the shops totals 43^ acres. A gigantic factory in a gigantic industry, Reo is a Lansing institution all the way through. Created and financed by Lan sing people, it is a remarkable example of self-containment and continuity of management. Through nearly two decades of successful operation its directorate has remained intact. Reo's commanding position in the industry is due to the quality of its products, to its policy of manufacturing the vehicles complete in its own shops, and to the diversity of the line. Five models of passenger cars, the Speed Wagon in twelve body styles, the Reo Taxicab, the Speed Wagon Parcel Delivery, and Reo Busses combine to represent the most com plete line of motor vehicles produced by any one factory in the world. If a visit to the Reo factory is not possible, request should be made for a copy of the 66-page book "Reasons for Reo." This is a resume of Reo's activities, and is sent without cost to anybody making the request. -

It Is My Honor to Recognize Members of the 53Rd and 181St Transportation Battalions As the “Senior Legends” of Our Time During the Cold War Era

TC COLD WAR HISTORY EDITION TWO It is my honor to recognize members of the 53rd and 181st Transportation Battalions as the “Senior Legends” of our time during the Cold War era. Among the names, we have wheeled vehicle operators, a platoon leader and heavy wheeled vehicle mechanics that supported the mission in the United States Army Europe. REMEMBER WHEN: Semaphores were a common signal device used on European automobiles, you wore a COMZ patch, you attended Head Start, your Mess Sergeant yelled all the time in the field, mess kits require three dips in the wash cycle, dip, wash and rinse, your Supply Sergeant stated you needed three copies per request “Triplicate” became a norm, Armed Forces Network still had one television channel and Radio Free America and Armored Forces Network radio were your two options, split rims were the danger in the motor park, driving on coble stone roads became an issue driving in the fall and winter, heating C-Rations on your manifold, the battalion safety patrol made your day on the Autobahn, the Willys M38 was replaced with the M151, The M52 replaced with the Autocar U7144T, your dispatch read, Belgium, Berlin, Holland, and France - COMZ, double clutch, construction of the Berlin Wall began on August 13, 1961. In 1963, the Rhein and Neckar freeze over. Apollo XI astronauts land on the Moon. You still had a M14 with Tripod. PAUL MC WILLIAMS, (84) enlisted into the US Army as a volunteer. Completed Basic Training and Advanced Individual Training at Camp Breckenridge, Kentucky in January 1953. -

From Farmland to Suburbia: Westtown Township

FROM FARMLAND TO SUBURBIA: WESTTOWN TOWNSHIP A History of Westtown Township, Chester County Pennsylvania POSTED JANUARY 22, 2020 A History of Westtown Township Chester County, Pennsylvania by Arthur E. James Originally Published in 1973 by The Chester County Historical Society Reprinted October 2000 by The Chester County Historical Society and Westtown Township Updated in 2019–20 by the Westtown Township Historical Commission copyright Westtown Township 2020 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION TO THE 2019 EDITION 1 ARTHUR JAMES’ 1973 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2 ABOUT ARTHUR E. JAMES, ORIGINAL AUTHOR OF THIS HISTORY 3 ABOUT WESTTOWN 4 BEFORE WILLIAM PENN — RICH INDIAN LEGACY 6 WELSH/WELCH TRACT 8 SOME EARLY SETTLERS 9 McDaniel Farm 14 Maple Shade Farm/Marshall Jones Farm/formerly Taylor Farm/now Pleasant Grove 15 Wynnorr Farm 17 Faucett/Cheyney Farm 21 Westtown School Farm/Pete’s Produce Farm 24 Bartram Farm 24 Crebilly Farm 25 NATURAL RESOURCES 26 A Well-watered Area 26 Township Sawmills and Gristmills 26 The Westtown School Sawmill of 1795 27 The Westtown School Gristmill and Sawmill, 1801–1914 28 The Hawley-Williams Mills near Oakbourne 29 Minerals and Construction Materials 30 Serpentine Quarries 30 The Osborne Hill Mine 34 Clay Deposits and the Westtown Pottery 35 TRANSPORTATION 38 Roads 38 Chester Road (Pennsylvania Route 352) 38 Street Road (Pennsylvania Route 926) 40 West Chester Pike (Pennsylvania Route 3) 41 Wilmington Pike (U.S. Route 202) 43 The Trolley Line Through Westtown 47 Railroads 49 The West Chester and Philadelphia Railroad 49 Westtown Station 50 Oakbourne Station 50 Chester Creek and Brandywine Railroad 54 MILITARY HISTORY 56 Revolutionary War 56 The War of 1812 59 Civil War 63 Camp Elder/Camp Parole 63 NOTEWORTHY EARLY DATED HOUSES 68 Oakbourne Mansion 68 The Smith Family Home 68 Oakbourne’s Architecture 71 The Water Tower 72 James C.