Brief History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of the Philippines Province of Pangasinan City of Urdaneta

Republic of the Philippines Province of Pangasinan City of Urdaneta Old City Hall Alexander Street, Poblacion Urdaneta City, 2428 Pangasinan, Philippines Phone: (075) 633-7080 New City Hall Mac Arthur Highway, Anonas Urdaneta City, 2428 Pangasinan, Philippines Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.urdaneta-city.gov.ph T ABLE OF CONTENTS Vision Mission Statement 1 Executive Agenda 2 Executive-Legislative Business for Progress 2 Historical Background 3 Demographic Profile 7 Geographic Location 11 Physical Features 12 Land Use 15 Infrastructure Facilities and Utilities 16 Social Service Facilities and Utilities 21 Economic Sector 35 Environmental Management Sector 37 Maps 39 Directories 46 VISION URDANETA CITY is envisioned to be a center of agri-industrial development and educational advancement, a city with viable solid waste management, admirable traffic system, sustainable social services and equitable opportunity, and a community of God-loving, well- disciplined, self-reliant, and development-oriented people. It shall be an urban growth center and a model of good governance in Northern Luzon. M ISSION URDANETA CITY is committed to provide adequate infrastructure facilities and basic social services to promote a healthy and safe environment, to practice good governance and dynamic leadership in ensuring political stability and economic self-sufficiency, and to promote people participation and policy formulation and project implementation. Page 1 EXECUTIVE AGENDA EXECUTIVE-LEGISLATIVE BUSINESS FOR PROGRESS Maximize the effective and efficient utilization of U nited action and common vision for a better Urdaneta government resources through innovative planning, progressive programming, and prudent spending. R evitalized communities as engines of progress D eveloped infrastructures to attract investments and Bring government services closer to the people by spur growth conducting mobile services and tapping alternative areas for revenue collections. -

Notices of the Pagan Igorots in 1789 - Part Two

Notices of the Pagan Igorots in 1789 - Part Two By Francisco A ntolin, 0 . P. Translated by W illiam Henry Scott Translator’s Note Fray Francisco Antolin was a Dominican missionary in Dupax and Aritao,Nueva Vizcaya,in the Philippines,between the years 1769 and 1789,who was greatly interested in the pagan tribes generally called “Igorots” in the nearby mountains of the Cordillera Central of northern Luzon. His unpublished 1789 manuscript,Noticias de los infieles igor- rotes en lo interior de la Isla de M anila was an attempt to bring to gether all information then available about these peoples,from published books and pamphlets, archival sources, and personal diaries, corre spondence, interviews and inquiries. An English translation of Part One was published in this journal,V o l.29,pp. 177-253,as “Notices of the pagan Igorots in 1789,” together with a translator’s introduction and a note on the translation. Part Two is presented herewith. Part Two is basically a collection of source materials arranged in chronological order, to which Esther Antolin added comments and discussion where he thought it necessary,and an appendix of citations and discourses (illustraciones) on controversial interpretations. With the exception of some of the Royal Orders (cedulas reales) ,these docu ments are presented in extract or paraphrase rather than as verbatim quotations for the purpose of saving space,removing material of no direct interest,or of suppressing what Father Antolin,as a child of the 18th-century Enlightenment, evidently considered excessive sanctity. Occasionally it is impossible to tell where the quotation ends and Father Antolin,s own comments begin without recourse to the original,which recourse has been made throughout the present translation except in the case of works on the history of mining in Latin America which were not locally available. -

Foreclosurephilippines.Com

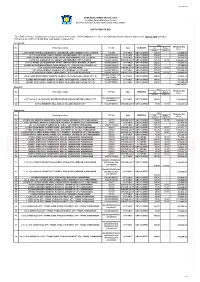

ITB - 06/23/2016 HOME DEVELOPMENT MUTUAL FUND La Union Housing Business Center Government Center, Sevilla, San Fernando City, La Union INVITATION TO BID The HDMF Committee on Disposition of Acquired Assets shall conduct a Public Bidding for the sale of the following acquired residential properties on July 12, 2018 starting at 8:00 AM at the 3rd Floor CB Mall Bldg., Nancayasan, Urdaneta City. La Union Br. Area Minimum Bid No. Property Location TCT No. Type REMARKS Lot House Price (sq.m.) (sq.m.) 1 L5/B02 NORTH FORBES SUBDIVISION, CATBANGEN, SAN FERNANDO CITY, LA UNION T-47499 LOT ONLY UNOCCUPIED 160.00 - 928,000.00 2 LOT 27259-B ZONE 3, BRGY. PARIAN, SAN FERNANDO CITY, LA UNION 025-2017000673 LOT ONLY UNOCCUPIED 278.00 - 764,500.00 3 L15/B07 EUFROSINA HEIGHTS SUBD., BIDAY, SAN FERNANDO CITY, LA UNION 025-2010002455 LOT ONLY UNOCCUPIED 176.00 - 985,600.00 4 L0T 08 INT. GABALDON ST., TANQUI, SAN FERNANDO CITY, LA UNION 025-2017000668 HOUSE & LOT UNOCCUPIED 157.00 98.76 3,084,843.25 5 LOT 2-C ROMEO DE GUZMAN EXT. ROAD, CENTRAL WEST, BAUANG, LA UNION 025-2016000875 LOT ONLY UNOCCUPIED 200.00 - 730,000.00 6 L10/B03 WOODSPARK ROSARIO SUBD. MOLAVE ST., CONCEPCION, ROSARIO, LU 025-2011000655 LOT ONLY UNOCCUPIED 139.00 - 347,500.00 7 LOT 359559-B SITIO NAGTONG-O, CALABA, ABRA 015-2017000010 HOUSE & LOT UNOCCUPIED 268.00 179.80 5,368,180.50 8 LOT 835-D-4-B BRGY. PUSSUAC, STO. DOMINGO, ILOCOS SUR 024-2017000722 LOT ONLY UNOCCUPIED 291.00 - 436,500.00 9 LOT 5528-B-10-D-2 BRGY. -

DAGUPAN CITY Auction

DAGUStar Plaza HotelPAN - A.B FernandezCITY Ave., Auct Dagupanion City February 07, 2012 Tuesday 2:00 pm 1-5 yrs 10% *Fixed interest rate for PA NGASINAN BENGUET & PANGASINAN 6-10yrs 12% installment terms PROPERTIES FOR AUCTION PROPERTIES FOR AUCTION February 07, 2012 February 09, 2012 Pangasinan ITEM A4 – Vacant Lot ITEM A6 - Vacant Lot Title ID : 6390 Title ID : 7243 TUESDAY • 2: 00 p.m. THURSDAY • 2: 00 p.m. ITEM A1 - Residential Lot Lot Area: 2,860.00 sqm. Lot Area: 33,804.00 sqm. Title ID : 6213 TCT # 67669 TCT # 120517 STAR PLAZA HOTEL HOTEL VENIZ Lot Area: 24,436.00 sqm. Lot 7764 Bonuan, Boquig, Dagupan Lot 10918 Brgy. Lunec, Malasiqui, A.B. Fernandez Avenue One Abanao Street TCT # 12482 to 12485 City Pangasinan Lots 5856, 5789, 10888 And 5850 Dagupan City Baguio City Market Price: 1,716,000.00 Market Price: 1,014,120.00 Brgy. Polo, Alaminos, Pangasinan Min. Bid Price : 1,210,000.00 Min. Bid Price : 850,000.00 Market Price: 2,443,600.00 Residential Lot Min. Bid Price : 1,650,000.00 ITEM A7 - House and Lot RESIDENTIAL LOT HOUSE & LOT Title ID : 14601 ITEM A2 - House and Lot ITEM A5 Lot Area: 1,461.00 sqm. Title ID : 7224 Title ID : 1451 Floor Area: 190.00 sqm. Lot Area: 862.00 sqm. Lot Area: 11,032.00 sqm. TCT # 236825 Floor Area: 100.00 sqm. TCT # 231922 Lot A Brgy. Pantal, Manaoag, TCT # 251945 Lot 1997 Brgy. Alacan, Malasiqui, Pangasinan Lot A-2-B-2 Brgy. Nibaliw, Bautista, Pangasinan Market Price: 2,012,000.00 Market Price: 3,088,960.00 Pangasinan Min. -

FILIPINOS in HISTORY Published By

FILIPINOS in HISTORY Published by: NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE T.M. Kalaw St., Ermita, Manila Philippines Research and Publications Division: REGINO P. PAULAR Acting Chief CARMINDA R. AREVALO Publication Officer Cover design by: Teodoro S. Atienza First Printing, 1990 Second Printing, 1996 ISBN NO. 971 — 538 — 003 — 4 (Hardbound) ISBN NO. 971 — 538 — 006 — 9 (Softbound) FILIPINOS in HIS TOR Y Volume II NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1990 Republic of the Philippines Department of Education, Culture and Sports NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE FIDEL V. RAMOS President Republic of the Philippines RICARDO T. GLORIA Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports SERAFIN D. QUIASON Chairman and Executive Director ONOFRE D. CORPUZ MARCELINO A. FORONDA Member Member SAMUEL K. TAN HELEN R. TUBANGUI Member Member GABRIEL S. CASAL Ex-OfficioMember EMELITA V. ALMOSARA Deputy Executive/Director III REGINO P. PAULAR AVELINA M. CASTA/CIEDA Acting Chief, Research and Chief, Historical Publications Division Education Division REYNALDO A. INOVERO NIMFA R. MARAVILLA Chief, Historic Acting Chief, Monuments and Preservation Division Heraldry Division JULIETA M. DIZON RHODORA C. INONCILLO Administrative Officer V Auditor This is the second of the volumes of Filipinos in History, a com- pilation of biographies of noted Filipinos whose lives, works, deeds and contributions to the historical development of our country have left lasting influences and inspirations to the present and future generations of Filipinos. NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1990 MGA ULIRANG PILIPINO TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Lianera, Mariano 1 Llorente, Julio 4 Lopez Jaena, Graciano 5 Lukban, Justo 9 Lukban, Vicente 12 Luna, Antonio 15 Luna, Juan 19 Mabini, Apolinario 23 Magbanua, Pascual 25 Magbanua, Teresa 27 Magsaysay, Ramon 29 Makabulos, Francisco S 31 Malabanan, Valerio 35 Malvar, Miguel 36 Mapa, Victorino M. -

2016 Was Indeed a Challenging and Fulfilling Year for the Mines and Geosciences Bureau-Regional Office No

Republic of the Philippines Department of Environment and Natural Resources MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU Regional Office No. 1 San Fernando City, La Union REGIONAL PROFILE ASSESSMENT Assessment Physical vis-a-vis Financial Performance Organizational Issues Assessment of Stakeholder’s Responses NARRATIVE REPORT OF ACCOMPLISHMENT General Management and Supervision MINERAL RESOURCE SERVICES Communication Plan for Minerals Development Geosciences and Development Services Geohazard Survey and Assessment Geologic Mapping Groundwater Resource and Vulnerability Assessment Miscellaneous Geological Services MINING REGULATION SERVICES Mineral Lands Administration Mineral Investment Promotion Program Mining Industry Development Program CHALLENGES FOR 2017 PERFORMANCE INFORMATION REPORT PHYSICAL ACCOMPLISHMENT vis-à-vis Prepared by: FUND UTILIZATION REPORT CHRISTINE MAE M. TUNGPALAN Planning Officer II ANNEXES MGB-I Key Officials Directory MGB-I Manpower List of Trainings Attended/Conducted Noted by: Tenement Map CARLOS A. TAYAG OIC, Regional Director REGIONAL PROFILE Region I, otherwise known as the Ilocos Region, is composed of four (4) provinces – Ilocos Norte, Ilocos Sur, La Union and Pangasinan – and nine (9) cities – Laoag, Batac, Candon, Vigan, San Fernando, Dagupan, San Carlos, Alaminos, and Urdaneta. The provinces have a combined number of one hundred twenty five (125) cities and municipalities and three thousand two hundred sixty five (3,265) barangays. Region I is situated in the northwestern part of Luzon with its provinces stretching along the blue waters of West Philippine Sea. Bounded on the North by the Babuyan Islands, on the East by the Cordillera Provinces, on the west by the West Philippine Sea, and on the south by the provinces of Tarlac, Nueva Ecija and Zambales. It falls within 15°00’40” to 18°00’40” North Latitude and 119°00’45” to 120°00’55” East Longitude. -

Region Name of Laboratory I A.G.S. Diagnostic and Drug

REGION NAME OF LABORATORY I A.G.S. DIAGNOSTIC AND DRUG TESTING LABORATORY I ACCU HEALTH DIAGNOSTICS I ADH-LENZ DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY I AGOO FAMILY HOSPITAL I AGOO LA UNION MEDICAL DIAGNOSTIC CENTER, INC. I AGOO MEDICAL CLINICAL LABORATORY I AGOO MUNICIPAL HEALTH OFFICE CLINICAL LABORATORY I ALAMINOS CITY HEALTH OFFICE LABORATORY I ALAMINOS DOCTORS HOSPITAL, INC. I ALCALA MUNICIPAL HEALTH OFFICE LABORATORY I ALLIANCE DIAGNOSTIC CENTER I APELLANES ADULT AND PEDIATRIC CLINIC & LABORATORY I ARINGAY MEDICAL DIAGNOSTIC CENTER I ASINGAN DIAGNOSTIC CLINIC I ATIGA MATERNITY AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER I BACNOTAN DISTRICT HOSPITAL I BALAOAN DISTRICT HOSPITAL I BANGUI DISTRICT HOSPITAL I BANI - RHU CLINICAL LABORATORY I BASISTA RURAL HEALTH UNIT LABORATORY I BAUANG MEDICAL AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER I BAYAMBANG DISTRICT HOSPITAL I BETHANY HOSPITAL, INC. I BETTER LIFE MEDICAL CLINIC I BIO-RAD DIAGNOSTIC CENTER I BIOTECHNICA DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY I BLESSED FAMILY DOCTORS GENERAL HOSPITAL I BLOODCARE CLINICAL LABORATORY I BOLINAO COMMUNITY HOSPITAL I BUMANGLAG SPECIALTY HOSPITAL (with Additional Analyte) I BURGOS MEDICAL DIAGNOSTIC CENTER CO. I C & H MEDICAL AND SURGICAL CLINIC, INC. I CABA DISTRICT HOSPITAL I CALASIAO DIAGNOSTIC CENTER I CALASIAO MUNICIPAL CLINICAL LABORATORY I CANDON - ST. MARTIN DE PORRES HOSPITAL (REGIONAL) I CANDON GENERAL HOSPITAL (ILOCOS SUR MEDICAL CENTER, INC.) REGION NAME OF LABORATORY I CANDON ST. MARTIN DE PORRES HOSPITAL I CARDIO WELLNESS LABORATORY AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER I CHRIST-BEARER CLINICAL LABORATORY I CICOSAT HOSPITAL I CIPRIANA COQUIA MEMORIAL DIALYSIS AND KIDNEY CENTER, INC. I CITY GOVERNMENT OF BATAC CLINICAL LABORATORY I CITY OF CANDON HOSPITAL I CLINICA DE ARCHANGEL RAFAEL DEL ESPIRITU SANTO AND LABORATORY I CLINIPATH MEDICAL LABORATORY I CORDERO - DE ASIS CLINIC X-RAY & LABORATORY I CORPUZ CLINIC AND HOSPITAL I CUISON HOSPITAL, INC. -

Manual on Family Planning Client Referral System for the Public Sector

Health Governance Resource Center MANUAL ON THE FAMILY PLANNING CLIENT REFERRAL SYSTEM FOR THE PUBLIC SECTOR May 2006 This publication was made possible through the support provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of contract No. 492-C-00-03-00024-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s)' and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements 1 List of Abbreviations 2 INTRODUCTION 3 I. Purpose of the FP Client Referral System 4 II. Scope of the FP Client Referral System 5 III. Elements of a Functional FP Client Referral System 6 IV. Organizing the Public Sector FP Client Referral System 7 V. Referral Procedures A. Referrals for FP Contraceptives & Pills 9 B. Referrals for BTL and NSV 13 C. Referrals for Consultation and Technical Evaluation 17 VI. Recording and Reporting 22 A. Referrror B. Receiving Provider VII. Monitoring and Evaluation 24 Annexes 25 A. Levels of Public Health Care and Service Capability for Family Planning B. Criteria for Selection of Private Providers C. Synopsis of Department of Health Administrative Order 158 D. Memorandum of Understanding E. Addendum Contract of services F. Referral slip for dispensing commodities G. Informed consent form for surgical sterilization H. Referral form for consultation/technical intervention I. Reporting tables for referror J. Reporting tables for receiving providers ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The development and production of this manual was made possible through the support and invaluable inputs of the following resource persons for which deep gratitude is extended by the authors: • The Provincial Population Office of Pangasinan under the stewardship of Ms. -

DIRECTORY of TREASURERS and ASSISTANT TREASURERS DOF-BLGF REGION 1 As of September 22, 2015

DIRECTORY OF TREASURERS and ASSISTANT TREASURERS DOF-BLGF REGION 1 As of September 22, 2015 NO. NAME POSITION MUNICIPALITY/CITY PROVINCE CONTACT NUMBER EMAIL ADDRESS 1 JOSEPHINE P. CALAJATE PT Ilocos Norte 09471706120 [email protected] DELFIN. S. RABANES APT Ilocos Norte 09192795544 [email protected] 2 MARIBETH A. NAVARRO ICO-PT Ilocos Sur 09177798181 3 FRANCIS REMEGUIS E. ESTIGOY PT La Union 09158077913 [email protected] BERNABE C. DUMAGUIN APT La Union 09175641901 [email protected] 4 MARILOU UTANES PT Pangasinan 09189368722 [email protected] ROMEO E. OCA APT-Admin Pangasinan 09993032342 CITY 1 SHIRLEY R. DELA CRUZ CT Alaminos City Pangasinan 09166058891 [email protected] ROLANDO T. AGLIBOT ACT Alaminos City Pangasinan 09198999575 [email protected] 2 VERONICA D. GARCIA CT Batac City Ilocos Norte 9497792229 [email protected] RONALD JOHN P. GARBRIEL ACT Batac City Ilocos Norte 09175057394 [email protected] 3 BERNARDITA B. MATI CT Candon City Ilocos Sur 09085480664 MARISSA LEONILA M. SOLIVEN ACT Candon City Ilocos Sur 09209620619 [email protected] 4 ROMELITA ALCANTARA CT Dagupan City Pangasinan 09178101206 [email protected] 5 ELENA V. ASUNCION CT Laoag City Ilocos Norte 09175702228 [email protected] EVELYN B. GAMAYO ACT-Admin Laoag City Ilocos Norte 09088740024 [email protected] DIOMEDES B. GAYBAN ACT-Ops Laoag City Ilocos Norte 09175700015 6 JOSEPHINE J. CARANTO CT San Carlos City Pangasinan 09299557594 [email protected] MARITES Q. CASTRO ACT San Carlos City Pangasinan 09275069516 [email protected] 7 EDMAR C. LUNA CT San Fernando City La Union 09189641994 [email protected] ELVY N. CASILLA ACT San Fernando City La Union 8 SANIATA A. -

Flood Modeling and Hazard Mapping Using Hypothetical and Extreme Rainfall Events in Bued-Angalacan River Basin, Pangasinan, Philippines

FLOOD MODELING AND HAZARD MAPPING USING HYPOTHETICAL AND EXTREME RAINFALL EVENTS IN BUED-ANGALACAN RIVER BASIN, PANGASINAN, PHILIPPINES 1 2 1 1 1 Annie Melinda Paz-Alberto , Armando N. Espino Jr. ,Nicasio C. Salvador , Eleazar V. Raneses Jr. , Jose T. Gavino Jr. , Bennidict P. Pueyo1 and Cristopher R. Genaro1 1Institute for Climate Change and Environmental Management, Central Luzon State University, Science City of Muñoz, Nueva Ecija 3120, Philippines, Email:[email protected] 2Land and Water Resources Management Center, College of Engineering, Central Luzon State University, Science City of Muñoz, Nueva Ecija 3120, Philippines KEYWORDS: HEC-HMS, HEC-RAS, Geographic Information System (GIS), Remote Sensing. ABSTRACT: Flood is an obstinate problem that needs to be addressed in a more scientific way in order to prevent or lessen its costly impacts to properties and human lives. This project was proposed and implemented in response for this need. Using the Bued-Angalacan River Basin as the study area, a flood model was developed using a framework that utilized field observations, Geographic Information System (GIS), and Remote Sensing (RS). The flood model consists of two components. The first component deals with the upstream watershed hydrology, wherein a hydrological model based on HEC HMS was developed to estimate how much runoff is produced during a rainfall event. The second component deals with the river and flood plain hydraulics which aims to determine the behavior of water coming from the upstream watershed as it enters the main river and travels downstream towards the sea. This was done using HEC RAS. The combination of HEC HMS and HEC RAS resulted into a flood model that can be used for a variety of purposes, one of this is for simulation of flooding due to hypothetical extreme rainfall events. -

Annual Report of the United States High Commissioner to the Philippine Islands

o I / . ,K UMASS/AMHERST |i>ii|i|ll!!!ll!ll!!ll! 354.S I 1979 - House Document No. Ill 3T2O66 0344 ^q^ , y The Sixth Annual Report of the United States High Commissioner to the Philippine Islands to the President and Congress of the United States Covering the Fiscal Year July 1, 1941 to June 30, 1942 Washington, D. €., Octobei 20, 1*142 78th Congress, 1st Session House Document No. Ill SIXTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE UNITED STATES HIGH COMMISSIONER TO THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING THE SIXTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE UNITED STATES HIGH COMMISSIONER TO THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS COVERING THE FISCAL YEAR JULY 1, 1941, TO JUNE 30, 1942 February 15, 1943.—Referred to the Committee on Insular Affairs and ordered to be printed UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1943 U LETTER OF SUBMITTAL To the Congress oj the United States: As required by section 7 (4) of the act of Congress approved March 24, 1934, entitled "An act to provide for the complete independence of the Philippine Islands, to provide for the adoption of a constitu- tion and a form of government for the Philippine Islands, and for other purposes," I transmit herewith, for the information of the Congress, the Sixth Annual Report of the United States High Com- missioner to the Philippine Islands covering the fiscal year beginning July 1, 1941, and ending June 30, 1942. Franklin D, Roosevelt, The White House, February 15, 1943. nx )» TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. General Statement 1 II. Military AND Naval Activities AND Civilian Defense 14 Military developments 14 Naval activities 17 Civilian welfare and defense___l 20 III. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population ILOCOS

2010 Census of Population and Housing Ilocos Norte Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population ILOCOS NORTE 568,017 ADAMS 1,785 Adams (Pob.) 1,785 BACARRA 31,648 Bani 948 Buyon 1,524 Cabaruan 1,437 Cabulalaan 748 Cabusligan 1,036 Cadaratan 1,156 Calioet-Libong 753 Casilian 901 Corocor 741 Duripes 989 Ganagan 734 Libtong 1,547 Macupit 635 Nambaran 965 Natba 501 Paninaan 401 Pasiocan 1,162 Pasngal 685 Pipias 983 Pulangi 1,076 Pungto 551 San Agustin I (Pob.) 475 San Agustin II (Pob.) 270 San Andres I (Pob.) 730 San Andres II (Pob.) 817 San Gabriel I (Pob.) 254 San Gabriel II (Pob.) 426 San Pedro I (Pob.) 379 San Pedro II (Pob.) 403 San Roque I (Pob.) 496 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Ilocos Norte Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population San Roque II (Pob.) 392 San Simon I (Pob.) 626 San Simon II (Pob.) 384 San Vicente (Pob.) 621 Sangil 985 Santa Filomena I (Pob.) 306 Santa Filomena II (Pob.) 326 Santa Rita (Pob.) 1,099 Santo Cristo I (Pob.) 436 Santo Cristo II (Pob.) 458 Tambidao 762 Teppang 707 Tubburan 823 BADOC 30,708 Alay-Nangbabaan (Alay 15-B) 1,049 Alogoog 920 Ar-arusip 872 Aring 1,328 Balbaldez 328 Bato 975 Camanga 1,087 Canaan (Pob.) 570 Caraitan 1,273 Gabut Norte 1,398 Gabut Sur 997 Garreta (Pob.) 1,343 Labut 759 Lacuben 1,327 Lubigan 1,186 Mabusag Norte 1,155 Mabusag Sur 1,165 Madupayas 848 Morong 785