Fare-Free Public Transport (Ffpt)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here in 2017 Sillamäe Vabatsoon 46% of Manufacturing Companies with 20 Or More Employees Were Located

Baltic Loop People and freight moving – examples from Estonia Final Conference of Baltic Loop Project / ZOOM, Date [16th of June 2021] Kaarel Kose Union of Harju County Municipalities Baltic Loop connections Baltic Loop Final Conference / 16.06.2021 Baltic Loop connections Baltic Loop Final Conference / 16.06.2021 Strategic goals HARJU COUNTY DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 2035+ • STRATEGIC GOAL No 3: Fast, convenient and environmentally friendly connections with the world and the rest of Estonia as well as within the county. • Tallinn Bypass Railway, to remove dangerous goods and cargo flows passing through the centre of Tallinn from the Kopli cargo station; • Reconstruction of Tallinn-Paldiski (main road no. 8) and Tallinn ring road (main highway no. 11) to increase traffic safety and capacity • Indicator: domestic and international passenger connections (travel time, number of connections) Tallinn–Narva ca 1 h NATIONAL TRANSPORT AND MOBILITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2021-2035 • The main focus of the development plan is to reduce the environmental footprint of transport means and systems, ie a policy for the development of sustainable transport to help achieve the climate goals for 2030 and 2050. • a special plan for the Tallinn ring railway must be initiated in order to find out the feasibility of the project. • smart and safe roads in three main directions (Tallinn-Tartu, Tallinn-Narva, Tallinn-Pärnu) in order to reduce the time-space distances of cities and increase traffic safety (5G readiness etc). • increase speed on the railways to reduce time-space distances and improve safety; shift both passenger and freight traffic from road to rail and to increase its positive impact on the environment through more frequent use of rail (Tallinn-Narva connection 2035 1h45min) GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF CLIMATE POLICY UNTIL 2050 / NEC DIRECTIVE / ETC. -

RESILIENT POISED for GROWTH Annual Report 2020 Paramount Values Sustainability As Part of Its Business Philosophy

RESILIENT POISED FOR GROWTH Annual Report 2020 Paramount values sustainability as part of its business philosophy. This Annual Report is printed on environmentally friendly paper. THE COMPANY 02 - 20 03 How We Create Value 04 Corporate Structure IN THIS 05 Corporate Profile 17 Corporate Information REPORT 18 Other Information THE STORY 21 - 59 22 Message from the Chairman 22-24 25 Management Discussion & Analysis Message from 36 Five-year Group Financial the Chairman Highlights 38 Sustainability Statement HOW WE ARE GOVERNED 60 - 88 61 Board of Directors’ Profile 70 Key Senior Management Profile 71 Corporate Governance Overview Statement 78 Internal Policies, Frameworks & 03 Guidelines How We 80 Audit Committee Report Create Value 83 Statement on Risk Management and Internal Control 05 - 16 THE FINANCIALS 89 - 217 Corporate 90 Directors’ Report Profile 96 Statement by Directors 96 Statutory Declaration 97 Independent Auditors’ Report 101 Consolidated Income Statement 102 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 103 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 105 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 107 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 110 Income Statement 111 Statement of Financial Position 113 Statement of Changes in Equity 115 Statement of Cash Flows 117 Notes to the Financial Statements OTHER INFORMATION 218 - 236 219 Analysis of Shareholdings 222 Analysis of Warrant Holdings 224 List of Top 10 Properties 225 Statement of Directors’ 25 - 35 Responsibility Management 226 Notice of Fifty-First Discussion & Analysis Annual General Meeting 231 Administrative Guide • Proxy Form THE 02 - 20 COMPANY 03 How We Create Value 04 Corporate Structure 05 Corporate Profile 17 Corporate Information 18 Other Information Annual Report 2020 03 THE COMPANY HOW WE CREATE VALUE Our Vision Our Core Values Changing RUST TWe will strive to strengthen the faith that our shareholders, customers and Lives And the community have placed upon us to deliver sustainable returns. -

Quattro West – Office to Let Persiaran Barat, Petaling Jaya

JLL Property Services (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd (640511-U) (fka YY Property Solutions Sdn Bhd) Unit 7.2, Level 7, Menara 1 Sentrum No 201 Jalan Tun Sambanthan, KL Sentral 50470 Kuala Lumpur. Malaysia tel: +603-22 600 700 | fax : +603-22 600 701 www.jll.com.my Quattro West – Office To Let Persiaran Barat, Petaling Jaya Property Highlights:- • Office unit size: 6,932 sq. ft. • Opportunity to let half of the office unit i.e., approx. 3,000 sq. ft. • Unit level: Ground floor • Furnishing: Fully – furnished • Asking rental rate: RM7 psf per month • Amenities: Restaurants, authentic Malaysian eateries, grocers, car park, public transport and etc. • Strategic and central location of Petaling Jaya, next to PJ Hilton Hotel and; within walking distance to public transportations Central Location Quattro West 1. Asia Jaya LRT Station 2. Taman Jaya LRT Station 3. PJ Hilton Hotel 4. Armada Hotel The Destination • 500m from Asia Jaya LRT Station • 5 minutes drive to Taman Jaya LRT Station • Next to PJ Hilton Hotel • Great frontage to Federal Highway For further enquiries, please contact: Joey Siw (REN00741) Syafiqah Yusof (REN00748) Marketing Hotline. +603-22 600 788 E. M. +60 19 662 2330 M. +60 16 203 9460 [email protected] DL. +60 3 22 600 705 DL. +60 3 22 600 713 YY LAU (MS) E. [email protected] E. [email protected] Country Head, E1260 Persons responding to this flyer are not required to pay any estate agency fee whatsoever for property referred to in this flyer as this company is already retained by a particular principal. -

Asyl-, Migrations- Och Integrationsfonden (AMIF)

1 Ansökan om stöd och projektplan Asyl-, migrations- och integrationsfonden (AMIF) Fylls i av funktionen för fonderna Projektnummer: Inkom: Åtgärdsområde: Denna versions nummer: Gemensam indikator: Datum för godkännande: Uppgifter om projektet Fylls i av projektägaren Namn på projektet "En väg in" – En inkluderande mötesplats för arbete och företagande Projektägare Hedemora kommun Startdatum Denna version reviderad: 2016-06-15 2016-06-08 Slutdatum Ursprunglig version upprättad: 2019-10-15 2016-02-10 Projektet söker finansiering inom specifik mål: (Välj ett område) Asyl Integration och laglig migration Återvändande Har projektet ansökt om medfinansiering från annan EU-fond? Om ja, ange vilken fond och beslut för ansökan: Ja Nej Har stödsökande och någon eller några av stödmottagarna i detta projekt, vilken/vilka bedriver en ekonomisk verksamhet, mottagit statsstöd i enlighet med artiklarna 107-109 i EUF-fördraget eller stöd av mindre betydelse under innevarande och de två närmast föregående beskattningsåren? Ja Nej Nej, vi är en myndighet. Fritext Kommer projektet att generera intäkter? Ja, beskriv vilken typ an intäkter som projektet kommer att generera: Nej Uppgifter om projektägarens organisation Organisationens namn Hedemora kommun Postadress Postnummer och ort Box 201 776 28 Besöksadress (gata och ort) Hemsida Hökargatan 6 Hedemora www.hedemora.se Organisationsform Organisationsnummer Lokala offentliga organ 212000-2254 Plusgiro-/bankgironummer Behörig firmatecknare Bankgiro 433-2409 Ulf Hansson Telefon/mobiltelefon E-postadress 0225-34170 [email protected] Kontaktperson för projektverksamhet Projektledare (för- och efternamn) Telefon/mobiltelefon Maria Lundgren 0225-34155 E-postadress [email protected] Kontaktperson för ekonomi Ansvarig för ekonomihantering (namn och befattning) Telefon/mobiltelefon Anna-Lotta Sjöstrand 0225-34004 E-postadress [email protected] Det här är ett projekt som finansieras av Europeiska unionen Asyl-, migrations och integrationsfonden 2 1. -

Estonian Ministry of Education and Research

Estonian Ministry of Education and Research LANGUAGE EDUCATION POLICY PROFILE COUNTRY REPORT ESTONIA Tartu 2008 Estonian Ministry of Education and Research LANGUAGE EDUCATION POLICY PROFILE COUNTRY REPORT ESTONIA Estonian Ministry of Education and Research LANGUAGE EDUCATION POLICY PROFILE COUNTRY REPORT ESTONIA Tartu 2008 Authors: Language Education Policy Profile for Estonia (Country Report) has been prepared by the Committee established by directive no. 1010 of the Minister of Education and Research of 23 October 2007 with the following members: Made Kirtsi – Head of the School Education Unit of the Centre for Educational Programmes, Archimedes Foundation, Co-ordinator of the Committee and the Council of Europe Birute Klaas – Professor and Vice Rector, University of Tartu Irene Käosaar – Head of the Minorities Education Department, Ministry of Education and Research Kristi Mere – Co-ordinator of the Department of Language, National Examinations and Qualifications Centre Järvi Lipasti – Secretary for Cultural Affairs, Finnish Institute in Estonia Hele Pärn – Adviser to the Language Inspectorate Maie Soll – Adviser to the Language Policy Department, Ministry of Education and Research Anastassia Zabrodskaja – Research Fellow of the Department of Estonian Philology at Tallinn University Tõnu Tender – Adviser to the Language Policy Department of the Ministry of Education and Research, Chairman of the Committee Ülle Türk – Lecturer, University of Tartu, Member of the Testing Team of the Estonian Defence Forces Jüri Valge – Adviser, Language Policy Department of the Ministry of Education and Research Silvi Vare – Senior Research Fellow, Institute of the Estonian Language Reviewers: Martin Ehala – Professor, Tallinn University Urmas Sutrop – Director, Institute of the Estonian Language, Professor, University of Tartu Translated into English by Kristel Weidebaum, Luisa Translating Bureau Table of contents PART I. -

The Environmental and Rural Development Plan for Sweden

0LQLVWU\RI$JULFXOWXUH)RRGDQG )LVKHULHV 7KH(QYLURQPHQWDODQG5XUDO 'HYHORSPHQW3ODQIRU6ZHGHQ ¤ -XO\ ,QQHKnOOVI|UWHFNQLQJ 7,7/(2)7+(585$/'(9(/230(173/$1 0(0%(567$7($1'$'0,1,675$7,9(5(*,21 *(2*5$3+,&$/',0(16,2162)7+(3/$1 GEOGRAPHICAL AREA COVERED BY THE PLAN...............................................................................7 REGIONS CLASSIFIED AS OBJECTIVES 1 AND 2 UNDER SWEDEN’S REVISED PROPOSAL ...................7 3/$11,1*$77+(5(/(9$17*(2*5$3+,&$//(9(/ 48$17,),(''(6&5,37,212)7+(&855(176,78$7,21 DESCRIPTION OF THE CURRENT SITUATION...................................................................................10 (FRQRPLFDQGVRFLDOGHYHORSPHQWRIWKHFRXQWU\VLGH The Swedish countryside.................................................................................................................... 10 The agricultural sector........................................................................................................................ 18 The processing industry...................................................................................................................... 37 7KHHQYLURQPHQWDOVLWXDWLRQLQWKHFRXQWU\VLGH Agriculture ......................................................................................................................................... 41 Forestry............................................................................................................................................... 57 6XPPDU\RIVWUHQJWKVDQGZHDNQHVVHVWKHGHYHORSPHQWSRWHQWLDORIDQG WKUHDWVWRWKHFRXQWU\VLGH EFFECTS OF CURRENT -

Guidelines for the Safe Siting of School Bus Stops

Guidelines for the safe location of school bus stops 1. How are bus stops determined? Bus stops will be placed on public roadways and will avoid travel on private roads and/or driveways Bus routes are designed with buses traveling on main arterials with students picked up and dropped off at central locations. Visibility – Bus drivers need to have at least 500 feet of visible roadway to the bus stop. If there is not ample visibility (e.g. curve or hill) a “school bus stop ahead sign” is put in place before the stop in accordance with WAC 392-145-030 Bus drivers activate their school bus warning lights 300-100 feet before arriving at the bus stop, where the posted speed limit is 35 mph and under, and 500-300 feet before arriving at the bus stop where the posted speed limit is 35 mph and over. 2. Why are bus stops located at corners? Bus stops may be located at corners or intersections whenever possible. Corner stops are much more visible to drivers than house numbers. Students are generally taught to cross at corners rather than in the middle of the street. Traffic controls, such as stoplights or signs, are located at corners. These tend to slow down motorists at corners, making them more cautious as they approach intersections. The motoring public generally expects school buses to stop at corners rather than individual houses. Impatient motorists are also less likely to pass buses at corners than along a street. Cars passing school buses create the greatest risk to students who are getting on or off the bus. -

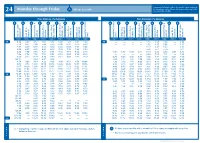

Monday Through Friday Mt

New printed schedules will not be issued if trips are adjusted Monday through Friday All trips accessible by five minutes or less. Please visit www.go-metro.com for the go smart... go METRO 24 most up-to-date schedule. 24 Mt. Lookout–Uptown–Anderson Riding Metro From Anderson / To Downtown From Downtown / To Anderson . 1 No food, beverages or smoking on Metro. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 2. Offer front seats to older adults and people with disabilities. METRO* PLUS 3. All Metro buses are 100% accessible for people 38X with disabilities. 46 UNIVERSITY OF 4. Use headphones with all audio equipment 51 CINCINNATI GOODMAN DANA MEDICAL CENTER HIGHLAND including cell phones. Anderson Center Station P&R Salem Rd. & Beacon St. & Beechmont Ave. St. Corbly & Ave. Linwood Delta Ave. & Madison Ave. Observatory Ave. Martin Luther King & Reading Rd. & Auburn Ave. McMillan St. Liberty St. & Sycamore St. Square Government Area B Square Government Area B Liberty St. & Sycamore St. & Auburn Ave. McMillan St. Martin Luther King & Reading Rd. & Madison Ave. Observatory Ave. & Ave. Linwood Delta Ave. & Beechmont Ave. St. Corbly Salem Rd. & Beacon St. Anderson Center Station P&R 11 ZONE 2 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 2 43 5. Fold strollers and carts. BURNET MT. LOOKOUT AM AM 38X 4:38 4:49 4:57 5:05 5:11 5:20 5:29 5:35 5:40 — — — — 4:10 4:15 4:23 — 4:35 OBSERVATORY READING O’BRYONVILLE LINWOOD 6. -

Right of Passage

Right of Passage: Reducing Barriers to the Use of Public Transportation in the MTA Region Joshua L. Schank Transportation Planner April 2001 Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee to the MTA 347 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10017 (212) 878-7087 · www.pcac.org ã PCAC 2001 Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank the following people: Beverly Dolinsky and Mike Doyle of the PCAC staff, who provided extensive direction, input, and much needed help in researching this paper. They also helped to read and re-read several drafts, helped me to flush out arguments, and contributed in countless other ways to the final product. Stephen Dobrow of the New York City Transit Riders Council for his ideas and editorial assistance. Kate Schmidt, formerly of the PCAC staff, for some preliminary research for this paper. Barbara Spencer of New York City Transit, Christopher Boylan of the MTA, Brian Coons of Metro-North, and Yannis Takos of the Long Island Rail Road for their aid in providing data and information. The Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee and its component Councils–the Metro-North Railroad Commuter Council, the Long Island Rail Road Commuters Council, and the New York City Transit Riders Council–are the legislatively mandated representatives of the ridership of MTA bus, subway, and commuter-rail services. Our 38 volunteer members are regular users of the MTA system and are appointed by the Governor upon the recommendation of County officials and, within New York City, of the Mayor, Public Advocate, and Borough Presidents. For more information on the PCAC and Councils, please visit our website: www.pcac.org. -

145 159 166 168 172 173 183 190 195 196 197 215 Vol. VII December

(ISSN 0275-9314) CONTENTS Sven Mattisson Trägårdh, Swedish Labor Leader and Emigrant 145 On the Ruhlin Ancestry 159 A Bibliographical Note on The Swedes in Illinois 166 Genealogical Queries from the Swedish House of Nobles 168 Rambo Birthplace Found 172 St. Ansgarius (Chicago) Marriages 1867-1879 (Continued) 173 Genealogical Queries 183 Literature 190 Roval Coin Cabinet to Honor New Sweden 1988 195 A Presidential Proclamation 196 Index of Personal Names 197 Index of Place Names 215 Vol. VII December 1987 No. 4 Copyright* 1987 Swedish American Genealogin! P.O. Box 2186 Winter Park. FL 32790 (ISSN 0275-9.114) Edilorand Publisher Nils William Olsson. Ph.D.. F.A.S.G. ( ontrihuling Editors Glen U. Brolandcr, Augustana College, Rock Island. 1L Sten Carlsson. Ph.D.. Uppsala University. Uppsala, Sweden Col. Erik Thorell, Stockholm. Sweden Erik Wikén, Ph.D.. Uppsala. Sweden Contributions are welcome but the quarterly and its editors assume no responsibility for errors of fact or views expressed, nor for the accuracy ol material presented in books reviewed. Queries arc printed free of charge to subscribers only. Subscriptions arc Slo.OO pel annum and run lor the calendar year. Single copies arc $5.00 each. In Sweden the subscript ion price is 125.00 Swedish */-<//»<.>/• per year for surface dcli\ery. I75.00/Uo/I«r lor air delivery. In Scandinavia the subscription fee maj be deposited in postgiro account No. 260 10-9. Swedish American GeneaiogUt, Box 2029. 103 II Stockholm. Argosy Tours Announces A HERITAGE TOUR OF SWEDEN 12-26 June 1988 Sponsored by Kalmar Nyckel Commemorative Committee of Wilmington. -

The Demand for Public Transport: a Practical Guide

The demand for public transport: a practical guide R Balcombe, TRL Limited (Editor) R Mackett, Centre for Transport Studies, University College London N Paulley, TRL Limited J Preston, Transport Studies Unit, University of Oxford J Shires, Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds H Titheridge, Centre for Transport Studies, University College London M Wardman, Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds P White, Transport Studies Group, University of Westminster TRL Report TRL593 First Published 2004 ISSN 0968-4107 Copyright TRL Limited 2004. This report has been produced by the contributory authors and published by TRL Limited as part of a project funded by EPSRC (Grants No GR/R18550/01, GR/R18567/01 and GR/R18574/01) and also supported by a number of other institutions as listed on the acknowledgements page. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the supporting and funding organisations TRL is committed to optimising energy efficiency, reducing waste and promoting recycling and re-use. In support of these environmental goals, this report has been printed on recycled paper, comprising 100% post-consumer waste, manufactured using a TCF (totally chlorine free) process. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The assistance of the following organisations is gratefully acknowledged: Arriva International Association of Public Transport (UITP) Association of Train Operating Companies (ATOC) Local Government Association (LGA) Confederation of Passenger Transport (CPT) National Express Group plc Department for Transport (DfT) Nexus Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Network Rail Council (EPSRC) Rees Jeffery Road Fund FirstGroup plc Stagecoach Group plc Go-Ahead Group plc Strategic Rail Authority (SRA) Greater Manchester Public Transport Transport for London (TfL) Executive (GMPTE) Travel West Midlands The Working Group coordinating the project consisted of the authors and Jonathan Pugh and Matthew Chivers of ATOC and David Harley, David Walmsley and Mark James of CPT. -

By the Numbers

By the Numbers Quantifying Some of Our Environmental & Social Work 6.2 MILLION 100 Dollars we donated this fiscal year Percentage of Patagonia products we take to fund environmental work back for recycling 70 MILLION 164,062 Cash and in-kind services we’ve donated since Pounds of Patagonia products recycled our tithing program began in 1985 or upcycled since 2004 741 84 Environmental groups that received Percentage of water saved through our new a Patagonia grant this year denim dyeing technology as compared to environmental + social initiatives conventional synthetic indigo denim dyeing 116,905 Dollars given to nonprofits this year through 100 our Employee Charity Match program Percentage of Traceable Down (traceable to birds that were never live-plucked, 20 MILLION & CHANGE never force-fed) we use in our down products 2 Dollars we’ve allocated to invest in environmentally and socially responsible companies through our 1996 venture capital fund Year we switched to the exclusive use of organically grown cotton 0 8 New investments we made this year through 10,424 $20 Million & Change Hours our employees volunteered this year 1 on the company dime 5 Mega-dams that will not be built on Chile’s Baker 30,000 and Pascua rivers thanks to a worldwide effort Approximate number of Patagonia products 5 in which we participated repaired this year at our Reno Service Center 380 15 MILLION Public screenings this year for DamNation Acres of degraded grassland we hope to restore in the Patagonia region of South America by buying and supporting the purchase of responsibly sourced 75,000 merino wool Signatures collected this year petitioning the Obama administration to remove four dams initiatives social + environmental on the lower Snake River 774,671 Single-driver car-trip miles avoided this year 192 through our Drive-Less program Fair Trade Certified™ styles in the Patagonia line as of fall 2015 100 MILLION Dollars 1% for the Planet® has donated to nonprofit environmental groups cover: Donnie Hedden © 2015 Patagonia, Inc.