DAY-DISSERTATION.Pdf (1.077Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WCWM Broadcasts Radio Justin Timberlake’S New Field Hockey Garners a No

U.S. Postage Paid at Williamsburg, Va. VARIETY: SPORTS: The Muscarelle hosts a unique Women’s exhibit of fl oral arrangements in- soccer goes spired by art on display, page 7. 3-1 in their four-game roadtrip, REVIEWS: page 7. Gym wear sparks an important fashion discussion, page 11. SEPTEMBER 15, 2006 VOL.96, NO.4 THE STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY SINCE 1911 http://flathat.wm.edu Starbucks may begin Williamsburg redevelopment SA to sliding doors and new paint colors “Iʼm getting older; Iʼve done a lot. sale, according to city offi cials. College Delly to will also be added to the exterior. I need to slow down and fi nd some “What weʼve heard from the A fi nal agreement has not been security for my family,” Tsamouras, City eyes more College makes sense to us,” provide become Starbucks reached, but Tsamouras said he who also owns the Yorktown Pub student-friendly Williamsburg Economic Devel- is interested in removing himself and Waterstreet Landing restaurants opment Manager Michele DeWitt from the day-to-day management in Yorktown, said. “I think [the Col- businesses said. “A year ago a survey of Wil- free blue BY JOSHUA PINKERTON of the property. Tsamouras was ap- lege Delly] needs new energy, and I liam and Mary students showed FLAT HAT EDITOR-IN-CHIEF proached by Starbucks and has re- donʼt have that energy anymore.” BY BENJAMIN LOCHER that they were looking for more re- books ceived several offers to lease the “Other suitors are perfectly THE FLAT HAT tail opportunities. -

Never Have I Ever: My Life (So Far) Without a Date

Begin Reading Table of Contents Newsletters Copyright Page In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. For Rylee, obviously. Introduction To the Lighthouse I WOULD LIKE TO TELL YOU about a theory I’ve developed, in the past two years or so, about a certain brand of people I like to call “lighthouses.” This theory was developed after years spent in the company of one such member of the species, carefully observed in her natural habitat. She was the prototype, basically. Her name is Rylee and she’s my best friend. You might as well know that now because she’s going to come up a lot. Rylee, since the time I met her seven years ago, has dated nine people. This is probably not remarkably high. It could even be average. What do I know? It could be that that number only seems large in comparison to my own figures, which are so low they’re practically negative. But what’s really crazy, what’s really impressive about it, is her lack of time off between boyfriends. When she’s single, Rylee hardly needs to leave the apartment (or, in some of those cases, dormitory building) before anywhere from one to four different guys profess an interest in being her next boyfriend. -

Swarthmore Folk Alumni Songbook 2019

Swarthmore College ALUMNI SONGBOOK 2019 Edition Swarthmore College ALUMNI SONGBOOK Being a nostalgic collection of songs designed to elicit joyful group singing whenever two or three are gathered together on the lawns or in the halls of Alma Mater. Nota Bene June, 1999: The 2014 edition celebrated the College’s Our Folk Festival Group, the folk who keep sesquicentennial. It also honored the life and the computer lines hot with their neverending legacy of Pete Seeger with 21 of his songs, plus conversation on the folkfestival listserv, the ones notes about his musical legacy. The total number who have staged Folk Things the last two Alumni of songs increased to 148. Weekends, decided that this year we’d like to In 2015, we observed several anniversaries. have some song books to facilitate and energize In honor of the 125th anniversary of the birth of singing. Lead Belly and the 50th anniversary of the Selma- The selection here is based on song sheets to-Montgomery march, Lead Belly’s “Bourgeois which Willa Freeman Grunes created for the War Blues” was added, as well as a new section of 11 Years Reunion in 1992 with additional selections Civil Rights songs suggested by three alumni. from the other participants in the listserv. Willa Freeman Grunes ’47 helped us celebrate There are quite a few songs here, but many the 70th anniversary of the first Swarthmore more could have been included. College Intercollegiate Folk Festival (and the We wish to say up front, that this book is 90th anniversary of her birth!) by telling us about intended for the use of Swarthmore College the origins of the Festivals and about her role Alumni on their Alumni Weekend and is neither in booking the first two featured folk singers, for sale nor available to the general public. -

Noir? She Asked, Nodding Toward the Sign Painted on the Street Window Behind You, Seen in Reverse from in Here: PHILIP M

Table of Contents Title Page Copyright Page Dedication NEW YORK: 141 Wooster Street New York, NY 10012 LONDON: 90-93 Cowcross Street London EC1M 6BF [email protected] www.ducknet.co.uk Copyright © 2010 by Robert Coover All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress eISBN: 9781590204924 http://us.penguingroup.com For Bernard Hoepffner, partner in crime. YOU ARE AT THE MORGUE. WHERE THE LIGHT IS WEIRD. Shadowless, but like a negative, as though the light itself were shadow turned inside out. The stiffs are out of sight, temporarily archived in drawers like meaty data, chilled to their own bloodless temperature. Their stories have not ended, only their own readings of them. In your line of work, this is not a place where things end so much as a place where they begin. Following the usual preamble: You were in your office late. The phone call came in. You pulled on your old trenchcoat with the torn pockets, holstered your heater under your armpit, and headed for the docklands. The scene of the crime. Nightmarishly dark as it usually is down there, even in the middle of most days, lit only by dull swinging streetlamps, the reflective wet streets more luminous than the lamps themselves, though casting no light of their own. -

From Truth to Reconciliation Th

AHF_School_cover_JAN23.qxd:Layout 1 1/23/08 3:57 PM Page 1 RESILIENCE OF THE FLOWER BEADWORK PEOPLE Christi Belcourt 1999 Acrylic on Canvas We have survived through incredible odds. We very easily could have been absorbed into the mainstream society. The pressures were there from all sides . No matter. We are here. Despite direct assimilation attempts. Despite the residential school systems. Despite the strong influences of the Church in Métis communities to ignore and deny our Aboriginal heritage and our Aboriginal spirituality. We are still able to say we are proud to be Métis. We are resilient as a weed. As beautiful as a wildflower. We have much to celebrate and be proud of. – Christi Belcourt (excerpt from www.belcourt.net) T r a F n s r BLOOD TEARS f o o Alex Janvier r m m 2001 i Acrylic on linen n T g From Truth to Reconciliation th r Painted on the artist’s 66 birthday, t u h Blood Tears is both a statement of e t Transforming the Legacy of Residential Schools Mr. Janvier’s sense of loss and a h L celebration of his resilience, made all e t g the more powerful with the inclusion o a c of a lengthy inscription painted in his y R own hand on the rear of the canvas. o e f The inscription details a series of c R losses attributed to the ten years o e he spent at the Blue Quills Indian s n i d Residential School: loss of childhood, c e language, culture, customs, parents, Aboriginal Healing Foundation i n l t grandparents, and traditional beliefs. -

Every- One's a Winner in U.S. Election

1980 • Our 41st Year! • 2020 PRST STD U.S Postage Paid Glens Falls, N.Y. Chronicle real estate º 18-22 PERMIT NO. 172 LG alert º 3 • Matt Rozell º 4 • Mark replies º 6 Free Circulation 19,000 © Copyright 2020 The Chronicle Phone: 518-792-1126 Thanksgiving Northern New York’s Leading Newspaper • Down to earth and growing • Vol. 41, No. 1,869 • November 12-18, 2020 issue 1 day early At the Pinnacle, of November’s heat wave Every- one’s a winner Chronicle photo/Mark Frost in U.S. election By Mark Frost Chronicle Editor The Democrats are winners be- cause Joe Biden will be the new President and Donald Trump will be gone. The Republicans are winners Chronicle editor Mark Frost writes: Northern New York, basking in because the “Blue Wave” that the the 70-degree November weather that went on for days, crowded prognosticators and politicos The Pinnacle overlooking Lake George Sunday afternoon. The forecast with Lake George Land Conservancy’s 1.5-mile trail also connects to Cat and certainty simply Analysis Thomas Mountains. It was our first time to The Pinnacle. It’s a very didn’t happen, in accessible hike. The trailhead is on Edgecomb Pond Road, near the Bolton Washington or in & opinion Conservation Club. There’s moderate elevation to the climb, but the much of the rest trail is mostly on ground and easy on feet and legs. People were of the country. lingering at the top, savoring the view of Lake George. Mark Frost photo Republicans have a real chance to keep control of the U.S. -

Pop / Rock Misto

CATALOGO LP prezzo POP / ROCK MISTO 2967 BRITISH EUROPEAN LP 3LP 100-TH WINDOW - MASSIVE ATTACK EUR 120,00 209 CASTLE BRITISH EUROPEAN 2LPLP ACKER BILK:THE COLLECTION EUR 23,30 35 BRITISH EUROPEAN LP AGNES BERNELLE - FATHER'S LYING DEAD ON THE IRONINGEUR BOARD 15,50 8283 ARISTA AIR SUPPLY - JUST AS I AM EUR 19,50 9564 ARISTA (Audiophile LP) ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - BROTHERS ON THE ROAD EUR 19,50 505 FLYING FISH USA AZTEC TWO-STEP/SEE IT WAS LIKE THIS...AN ACOUSTIC RETROSPEC.EUR 14,50 163 CASTLE BRITISH EUROPEAN 2LPLP BARBARA DICKSON EUR 23,30 8620 ART BILL HALEY - GREATEST HITS EUR 15,50 15 BRITISH EUROPEAN LP - Heavy VinylBILL WELLS TRIO - ALSO IN WHITE EUR 22,50 4 AUDIOPHARM 3 LP BRAZILECTRO 3 - Artisti Vari - Jazz-Samba and Electronic Music: EURBossa & Latin 34,00 - composta da uno dei più popolari DJ nel mondo - Paco De La Cruz 5 AUDIOPHARM 3 LP BRAZILECTRO 4 - Artisti Vari - Jazz-Samba and Electronic Music: EURBossa & Latin 34,00 - - composta da uno dei più popolari DJ nel mondo - Paco De La Cruz 18 CASTLE BRITISH EUROPEAN LP CHICAGO: CHICAGO 8 \ STREET PLAYER EUR 23,30 8619 ART CLIFF RICHARD - GREATEST HITS EUR 15,50 71302 GOLD CASTLE COLLINS JUDY /TRUST YOUR HEART EUR 13,90 166 CASTLE BRITISH EUROPEAN 2LPLP ELKIE BROOKS EUR 23,30 74213 BRITISH EUROPEAN LP 2 LP FRANK ZAPPA - SAMPLER - YOU CAN'T DO THAT ON STAGE ANYMOREEUR 18,50 229 CASTLE BRITISH EUROPEAN 2LPLP GARY NUMAN - THE COLLECTION EUR 23,30 129 CASTLE BRITISH EUROPEAN 2LPLP JUDY GARLAND - THE COLLECTION - LIVE! EUR 23,30 130 CASTLE BRITISH EUROPEAN 2LPLP MANTOVANI AND HIS ORCHESTRA - THE COLLECTION EUR 23,30 4402 CARTHAGE REC. -

Riverside Label Discography

Discography of the Riverside Label The Riverside label was established in 1953 by traditional jazz enthusiasts Bill Grauer and Orrin Keepnews in New York City. Originally Grauer and Keepnews intended to reissue classic jazz that they purchased from long defunct labels. Later the label recorded jazz, folk, comedy, spoken word, sound effects, children’s and gospel. Shortly after starting the Riverside label, Grauer went to Richmond Indiana, to see Harry Gennett Jr. to try to purchase the recordings of the Gennett label. The Gennett Record label was formed in 1918 as a division of the Starr Piano Company in Richmond Indiana. In the early 20’s, the label started recording the early jazz bands that were performing in Chicago. Gennett made the first recordings of Ferd “Jellyroll” Morton, King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band with Louis Armstrong and the Wolverines with Bix Beiderecke. The first recording of “Stardust” was made by its author Hoagy Carmichael in the Gennett Richmond studio The Gennett label had ceased operation in 1932, but many of the historic metal recording plates were still stored in Richmond. Grauer was able to purchase all of the remaining plates for $2000. Grauer began a massive reissue campaign, releasing much of the Gennett material on long playing albums for the first time. Later, Grauer obtained masters from other early jazz and blues labels, including Paramount, Circle, and QRS, and reissued that material. Although the early catalog of Riverside releases contained mostly purchased material, Riverside started recording jazz sessions on its own, including Thelonious Monk, Randy Weston, Wes Montgomery and Cannonball Adderley. -

Ebk-Jmca2.Pdf

Cracked Altimeter Volume 2 Joe Milford BlazeVOX [books] Buffalo, New York Cracked Altimeter by Joe Milford Copyright © 2008 Published by BlazeVOX [books] All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the publisher’s written permission, except for brief quotations in reviews. Printed in the United States of America Book design by Geoffrey Gatza Ebook edition BlazeVOX [books] 14 Tremaine Ave Kenmore, NY 14217 [email protected] publisher of weird little books BlazeVOX [ books ] blazevox.org 2 4 6 8 0 9 7 5 3 1 Table of Contents theory of dealing with my girl........................................................................ 13 my torso bare under cotton sheets 2 a.m......................................................... 13 millions of lives............................................................................................. 14 machines for Venus from her crippled lover................................................... 15 your scars are my landmarks.......................................................................... 24 incest with a flower........................................................................................ 25 bad break-up.................................................................................................. 26 hunting harts and foxes.................................................................................. 26 when . ......................................................................................................... 28 it’s time for . ............................................................................................. -

Skeleton-Crew-Stephen-King-Use

This book is for Arthur and Joyce Greene I’m your boogie man that’s what I am and I’m here to do whatever I can ... —K.C. and the Sunshine Band Contents Title Page Dedication Epigraph Introduction The Mist Here There Be Tygers The Monkey Cain Rose Up Mrs. Todd’s Shortcut The Jaunt The Wedding Gig Paranoid: A Chant The Raft Word Processor of the Gods The Man Who Would Not Shake Hands Beachworld The Reaper’s Image Nona For Owen Survivor Type Uncle Otto’s Truck Morning Deliveries (Milkman #1) Big Wheels: A Tale of The Laundry Game (Milkman #2) Gramma The Ballad of the Flexible Bullet The Reach Notes Copyright Page Do you love? Introduction Wait—just a few minutes. I want to talk to you ... and then I am going to kiss you. Wait ... I Here’s some more short stories, if you want them. They span a long period of my life. The oldest, “The Reaper’s Image,” was written when I was eighteen, in the summer before I started college. I thought of the idea, as a matter of fact, when I was out in the back yard of our house in West Durham, Maine, shooting baskets with my brother, and reading it over again made me feel a little sad for those old times. The most recent, “The Ballad of the Flexible Bullet,” was finished in November of 1983. That is a span of seventeen years, and does not count as much, I suppose, if put in comparison with such long and rich careers as those enjoyed by writers as diverse as Graham Greene, Somerset Maugham, Mark Twain, and Eudora Welty, but it is a longer time than Stephen Crane had, and about the same length as the span of H. -

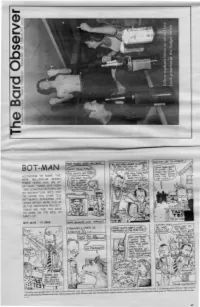

Bot-Man According to Some, the New Millenium Began Three Years Ago

BOT-MAN ACCORDING TO SOME, THE NEW MILLENIUM BEGAN THREE YEARS AGO. WE AT BAT-MAN THINK IT'S HIGH TIME SOMEONE NOTICED. SO IN CELEBRATION,WE'D LIKE TO SHOW YOU SOME OLD BOT-MAN'S SPANNING THE YEARS WHICH WERE DUG UP IN THE ARCHIVING PROJECT. TODAY WE TAKE YOU BACK TO BARD IN THE 80'5, IN PART 1 OF: BOT-MAN - Y1.996K <..SOC"\~t)'( ST"ot..€ 1'"Hc C~SE.'lTE -r-f'-'Pt -.....1'1'){Tri f. i,ti. ~ ~ nit. Cor'\ f l)O?. b C.Lf ANl) 'Rt.PLM.£1;) IT 't-lml 'BO'('6lPR tID cu~ a.i.110! le\ ~ -Createdby and copyrightChris Van Dyke &John Hollowach,1999. Specialthanks to Bard Housingfor introducingtkJnns with trailer hitchesinto our lives;Mr. T, for pitying UJ fools; ProfessorSkiff. for prob ably not knowing that Rotman even exists;Alf, for beinga part of the Westerncanon that Harold Bloomforgot to mention;and all my friends,for playing that tediousgame of "Which of thesetwo jokes arefun- _.:,.r+?" PAGE2 The Bard Observer NEWS September 24, 7999 inside the At Home with Range: NEWS Housing Crisis, Fall '99 Bard Charter School Ready to Break New Ground Students copewith "temporary"living conditions page3 Q By Briana Avinia-Tapper E i-"l..'.'!l- A Glimpse into the Mind of Gehry DURING THE FIRST three wet weeks of the ~ page3 Language and Thinking Workshop, white mobile ~ homes sprouted like mushrooms on Bard campus j between the Student Center and th'! Ravines. j The trailers are the hurried adjustment to an unusually large first-year class. -

Lindsay Lohan Sings of Endings

Lindsay Lohan Sings of Endings Rachel Tanner I don’t know if I love Kurt, but he does have a car. I love his car, maybe. Does that count for anything? Probably not. Do I love him? I don’t know. It’s 2005 and we’re two teenagers in maybe-love, cruising down the main thoroughfare in his car that smells very specifically like a slightly moldy boat floating on Pine-Sol instead of water. I’m 14 and he’s 16; we’re Lindsay Lohan young and running out of things to do in our one-Applebee’s town, so sometimes we just “Over” park next to the woods and read the Bible out loud to each other. I keep a stack of CDs in his car, choosing moment-by-moment soundtracks. Choosing how we will remember each Speak other. Choosing the sounds that will turn into forevers. Today, we listen to Something 12/2004 Corporate’s North and study the Book of Isaiah. Universal Island Records Lindsay Lohan’s Speak carries us home before curfew. We’re only one grade apart, but 9th grade is at the middle school and 10th grade is at the high school. It’s hard to be in a long-distance relationship. It is excruciating to be so far apart. Our schools are on the same road, 1.5 miles from each other, and our church is in the middle. Also, and I may have mentioned this already, he has a car. The car makes things easier. ----- In the beginning of us, back in the late fall of 2004, AOL Instant Messenger helped me lay the necessary groundwork for our relationship.