1857 and Its Lessons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

The Legacy of Henry Martyn to the Study of India's Muslims and Islam in the Nineteenth Century

THE LEGACY OF HENRY MARTYN TO THE STUDY OF INDIA'S MUSLIMS AND ISLAM IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY Avril A. Powell University of Lincoln (SOAS) INTRODUCTION: A biography of Henry Martyn, published in 1892, by George Smith, a retired Bengal civil servant, carried two sub-titles: the first, 'saint and scholar', the second, the 'first modern missionary to the Mohammedans. [1]In an earlier lecture we have heard about the forming, initially in Cambridge, of a reputation for spirituality that partly explains the attribution of 'saintliness' to Martyn: my brief, on the other hand, is to explore the background to Smith's second attribution: the late Victorian perception of him as the 'first modern missionary' to Muslims. I intend to concentrate on the first hundred years since his ordination, dividing my paper between, first, Martyn's relations with Muslims in India and Persia, especially his efforts both to understand Islam and to prepare for the conversion of Muslims, and, second, the scholarship of those evangelicals who continued his efforts to turn Indian Muslims towards Christianity. Among the latter I shall be concerned especially with an important, but neglected figure, Sir William Muir, author of The Life of Mahomet, and The Caliphate:ite Rise, Decline and Fall, and of several other histories of Islam, and of evangelical tracts directed to Muslim readers. I will finish with a brief discussion of conversion from Islam to Christianity among the Muslim circles influenced by Martyn and Muir. But before beginning I would like to mention the work of those responsible for the Henry Martyn Centre at Westminster College in recently collecting together and listing some widely scattered correspondence concerning Henry Martyn. -

United Nations Environmental Program Archive of E-Articles 2013

United Nations Environmental Program Archive of E-Articles 2013 January 2013 Sacred Sites Research Newsletter (SSIREN) To read the SSIREN Newsletter, visit: http://fore.research.yale.edu/files/SSIREN_January_2013.pdf January 2, 2013 Playing offense It’s time to divest from the oil industry By Bill McKibben The Christian Century The pipeline blockaders in the piney woods of East Texas that Kyle Childress describes ("Protesters in the pews," Christian Century, January 9, 2013) are American exemplars—the latest incarnation of John Muir, Rachel Carson, John Lewis or Fannie Lou Hamer. They’re playing defense with verve and creativity—blocking ugly and destructive projects that wreck landscapes and lives. And defense is crucial. As generations of sports coaches have delighted in pointing out, defense wins games. But we’re very far behind in the global warming game, so we need some offense too. And here’s what offense looks like: going directly after the fossil fuel industry and holding it accountable for the rapid warming of the planet. It’s the richest and most arrogant industry the world has ever seen. Call it Powersandprincipalities, Inc. And where once it served a real social need—energy— it now stands squarely in the way of getting that energy from safe, renewable sources. Its business plan—sell more coal, gas and oil—is at odds with what every climate scientist now says is needed for planetary survival. If that sounds shocking, sorry: a lifetime of Exxon ads haven’t prepared us for the reality that Exxon is a first-class villain, any more than a lifetime of looking at the Marlboro Man prepared us to understand lung cancer. -

Reviews of Books 515

Reviews of Books 515 This atlas, however, needs a major warning under the trade descriptions act. Even though, as it almost admits itself, more Muslims live east of Afghanistan than to the west, the focus is almost entirely on the Muslim world from Afghanistan to the Atlantic Ocean. Just four of the forty-four maps in the History and Politics section address the Islamic world east of Afghanistan; three maps address issues of water in the Sahara, the Jordan Valley and Turkey and Mesopotamia, but no attention is paid to water matters in the Indus Valley and the Ganges/Brahmaputra valleys where very much larger numbers of Muslims are affected by problems of water management and international rivalry for the resource; the map of holy sites and religious centres in the Muslim world has just three not very appropriate mentions for the area east of Afghanistan, placed almost as though they were an afterthought. Indeed, the structure and feel of this atlas is of a project designed to cover the Muslim world from Afghanistan westwards, and that is precisely the area shown in the picture on the front of the book. It would appear that perhaps the marketing department at Brill decided towards the end of the project that a focus just on the western lands of Islam would not do; the atlas had to claim, however inaccurately, to cover the whole of it. Whatever the reason for the pretensions of the title, the disproportionate coverage is a disgrace. And not least because it has been in the years 1800–2000 covered by the atlas that first the Muslims of South Asia, and then those of Southeast Asia, have come to have increasingly a leading role to play in Islamic civilisation. -

Journal of Indian Studies Vol

Journal of Indian Studies Vol. 5, No. 1, January – June, 2019, pp. 15 – 26 Indology and Indologist: Conceiving India during Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries Adnan Tariq Government Islamia College Civil Lines, Lahore, Pakistan. ABSTRACT This research paper is about the brief introduction of the major names in the field of Indology in the specified centuries of eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Further focus is on the inclusion of only British indologist to make it more precise in its subject matter. It would be argued that Indology as a discourse emerged with the change in policies by the authorities of East India Company and British Government. Earlier one genre of indologist comprised those missionary personalities, which were in India with missionary purpose and for that purpose; they had studied the languages and culture of India to familiarize with the proselytizing needs. In the swift next period another genre came into front with the newly acquired understanding of India as a land of those Hindus who had been noble savages and needs to be freed from the clutches of in-between invasion which had corrupted their soul. Then, the main exponents of indologist came into who propagated the immaculate justification of colonialism with scientific and comprehensible study of Indian subcontinent. All those different types of indologist were confined to the late eighth and nineteenth centuries. Thus, this research paper would try to present the life and works of only those indologist who fell in those described categories. Kew Words: Indology, British Government, East India Company, Hindu, Indian, Sub-continent Introduction Indology is the study of India. -

Journal of Indian Studies Vol

Journal of Indian Studies Vol. 5, No. 1, January – June, 2019, pp. 17 – 28 Indology and Indologist: Conceiving India during Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries Adnan Tariq Government Islamia College Civil Lines, Lahore, Pakistan. ABSTRACT This research paper is about the brief introduction of the major names in the field of Indology in the specified centuries of eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Further focus is on the inclusion of only British indologist to make it more precise in its subject matter. It would be argued that Indology as a discourse emerged with the change in policies by the authorities of East India Company and British Government. Earlier one genre of indologist comprised those missionary personalities, which were in India with missionary purpose and for that purpose; they had studied the languages and culture of India to familiarize with the proselytizing needs. In the swift next period another genre came into front with the newly acquired understanding of India as a land of those Hindus who had been noble savages and needs to be freed from the clutches of in-between invasion which had corrupted their soul. Then, the main exponents of indologist came into who propagated the immaculate justification of colonialism with scientific and comprehensible study of Indian subcontinent. All those different types of indologist were confined to the late eighth and nineteenth centuries. Thus, this research paper would try to present the life and works of only those indologist who fell in those described categories. Kew Words: Indology, British Government, East India Company, Hindu, Indian, Sub-continent Introduction Indology is the study of India. -

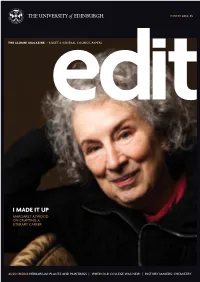

I Made It up Margaret Atwood on Crafting a Literary Career

WINTER 2014 | 15 THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE + BILLET & GENERAL COUNCIL PAPERS I MADE IT UP MARGARET ATWOOD ON CRAFTING A LITERARY CAREER ALSO INSIDE HERBARIUM: PLANTS AND PAINTINGS | WHEN OLD COLLEGE WAS NEW | HISTORY MAKERS: CHEMISTRY WINTER 2014 | 15 CONTENTS FOREWORD CONTENTS elcome to the winter edition of Edit. Edinburgh 08 16 W and Scotland have a place in the hearts of countless people throughout the world, and the leading poet and author Margaret Atwood is no exception. She Inspiration can be your legacy spoke to Edit as she received an honorary degree from the University of Edinburgh, and her interview on pages “A university and a gallery have much in common. 6-7 is a characteristic blend of humour and insight, taking in the power of access to higher education to bring 10 12 Challenging. Beautiful. Visionary. about social change, and including a mention of Irn-Bru. Designed to inspire the hearts and minds Anniversaries crop up throughout this edition of your magazine. A ceremony launching a major refurbishment of of the leaders and creators of tomorrow.” Old College also celebrated the laying of the foundation Pat Fisher, Principal Curator, stone 225 years ago. We open the cabinet doors of one of 18 Talbot Rice Gallery www.ed.ac.uk/talbot-rice the world's leading herbariums, which, jointly founded by the University in the 19th century, has been in its current home for 50 years. We also examine the University's unique relationship with China as the Confucius Institute for Scotland passes its 10th birthday. Edit itself moves with the times, and as we publish our latest printed magazine, 04 Digital Edit tu18 Wha Yo Did Next we have a new suite of digital offerings, all of which include additional multimedia content. -

Interaction of Sir Sayyid Ah,Mad Khān and Sir William Muir on H,Adīth

Chapter 1: Interaction of Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khān and Sir William Muir on Hadīth literature In Western scholarly studies on Hadīth material as well as in attempts to recon- struct a historical biography of Muhammad, the work of Sir William Muir in the middle of the nineteenth century is often over-looked. Not only did he produce one of the first biographies of Muhammad in the English language based on primary sources, he also formulated a thorough critique of the Hadīth and a methodology with which to sift what he considered historically accurate traditions from spurious ones. Subsequent scholars tended to reach very similar conclusions in their evaluation of the authenticity of the his- torical accounts contained within this body of traditions that formed the basis of not only the Muslim perception of their Prophet, but the foundation of the early development of Islam and the Muslim legal system as well. Muir’s contribution was unique in the West not only in its pioneering use of early Muslim sources, but also in that the context in which he wrote made Muslim evaluation of his research both immediate and interactive. A contemporary of Muir who responded to his Life soon after its publication was Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khān. He wrote his Essays in which he sought to answer a number of Muir’s criticisms; the book was later published in a more complete form in Urdu as Al-Khutubāt al-Ahmadīyah ‘alā al-‘Arab wa al-Sīrah al Muhammadīyah in 1887. Unlike many of the European Orientalists, Muir lived, worked, and conducted his research in an Islamic context where he had the benefit of interaction with believing Muslims such as Ahmad Khān who, while trained in the traditional ap- proach to the Hadīth, were also active in seeking to reform this classical approach in or- der to meet the needs of the contemporary Muslim community. -

The Turret Wellington School Magazine Spring/Summer 2019 Contents Welcome from Mr Johnson, Headmaster

The Turret Wellington School magazine Spring/Summer 2019 Contents Welcome From Mr Johnson, Headmaster Before writing this short introduction, I sat down to look through a draft - Headmaster’s Welcome 1 version of this publication. Inevitably, as I turned the pages, the hours - Why Wellington? 2-5 passed as each story brought back memories of a year packed full of - 2019 Sports Day 6-8 events, activities, productions and achievements. It is hard to do justice - 2019 House Report 9 to the sheer richness and variety of Wellington life. - S2/3 Mini Book Reviews 10-11 - Art & Design 12-13 Opportunities abound and I am delighted that so many of our pupils - P7 History Trip to Bannockburn 14 choose to make the most of them. Whether it be signing up for a - Outdoor Education 15 trip, entering a competition or taking part in a production, just getting - Junior School Production of Aladdin 16-18 involved can be the first step to something really special. So often, the - Autism Poem 19 activities that people enjoy throughout life are the ones that they first - Wellington take an Erasmus+ Trip to Macedonia 20-21 encountered at school. - S1 STEM Trip to Prestwick Airport 22-23 - Gradparents’ Day in the Junior School 24-25 I hope that you enjoy reading this edition of the ‘Turret’ as much as I - S6 Charity Cheque Presentation 26 did. The narrative of Wellington is written in its pages and I pay proper - Junior Erasmus Club 27 tribute to all of the pupils and staff, without whose energy and zest for - 2019 French Exchange Trip 28-29 life none of these stories would have been written. -

Marginal Muslims: Maulawis, Munsifs, Munshis and Others Avril Powell

Marginal Muslims: maulawis, munsifs, munshis and others Avril Powell (SOAS) (Work in progress: not to be cited) The paper will examine patterns of response to the events of 1857-58 among some Muslim civil servants employed in the subordinate services in the North-Western Provinces in positions such as sadr amin and deputy collector, and also as professors and teachers in the Anglo-Oriental colleges of the region, notably in Delhi, Agra and Bareilly. Many were of maulawi background and education, but unlike those ‘ulama more directly associated with mosque and madrassa functions, whose involvements in 1857 have been examined previously in several other studies, the responses of the ‘service’ category, with the exception of some well known figures such as Saiyid Ahmad Khan, have had little critical attention so far. The longer-term objective will be to disaggregate this service class to chart and evaluate some specific perceptions of events and decisions on stances and involvement, before, during and in the aftermath of rebellion. The present paper merely provides an entrée to this topic. In returning to this subject for the purposes of this conference after about fifteen years it should be considered whether studies completed in the interim now necessitate some questioning of my own earlier conclusions on Muslim involvement in the rebellions. But in fact, if anything, the more recent publications on Muslim issues in this period, have tended to reinforce the two-fold division of views predominant in the 1950s to 1980s between those arguing, either, that members of the religious class of ‘ulama spearheaded and acted in unison during the rebellion; or, that although some Muslims of various classes and categories can certainly be identified as committed ‘rebels’, there is little evidence of co-ordination among them, nor did they belong to a specific ‘religious’ category’ within Islam. -

The Case of Nilakanth-Nehemiah Goreh, Brahmin Convert Richard Fox Young

Enabling Encounters: The Case of Nilakanth-Nehemiah Goreh, Brahmin Convert Richard Fox Young n the preface of The Spirit Catches You and You Fall ous evidence. First, at the high end, the Indian corollary to an IDown: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Colli- “ivory tower” intellectual, I adduce Vitthal Shastri, a Maratha sion of Two Cultures, author Anne Fadiman, a self-described pandit who taught Hindu philosophy at the Benares Sanskrit “cultural broker,” sets forth her reasons for writing the book. I College, which had been established with British patronage in find them more broadly relevant than she perhaps anticipated. the last decade of the eighteenth century. The missionaries, he They are intriguingly descriptive of the creative possibilities explained, “mistake our silence. When a reply which we think awaiting people who situate themselves between cultures, soci- nonsense, or not applicable, is offered to us, we think that to retire eties, and religions: “I have always felt that the action most worth silently and civilly from such useless discussion is more merito- watching is not at the center of things but where the edges meet. rious than to continue it. But our silence is not a sign of our . There are interesting frictions and incongruities in these admission of defeat, which the Missionaries think to be so.”3 places, and often, if you stand at the point of tangency, you can I shall return to Vitthal Shastri later, for the most interesting see both sides better than if you were in the middle of either cross-cultural intellectual activity taking place in Benares in- one.”1 The mission history of nineteenth-century India, indisput- volved the Sanskrit College. -

The Relations Between Muslims and Protestan

I - 2 CONTACT AND CONTROVERSY BETWEEN ISLAM AND CHRISTIANITY IN NORTHERN INDIA, 1833-1857: THE RELATIONS BETWEEN MUSLIMS AND PROTESTANT MISSIONARIES IN THE NORTH-WESTERN PROVINCES AND OUDH by AVRIL ANN POWELL (School of Oriental and African Studies) Thesis submitted to the University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 1983 ProQuest Number: 11010473 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010473 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 3 ABSTRACT In the period 1833 to 1857 some 'ulama from the three north Indian cities of Lucknow, Agra and Delhi were drawn into open controversy with Protestant missionaries in the region. Initial contacts which began in Lucknow in 1833, were turned into prolonged and bitter encounter in the North-Western Provinces, by the dissemination from Agra of publications against Islam by a German Pietist missionary, the Reverend Carl Pfander^/ The two-fold objective of the thesis is to throw light on the backgrounds and motives of his 'ulama opponents, and to examine the types of argument they used in response to his evangelical challenge.