From Student to Researcher’ in the Digital Age: Exploring the Affordances of Emerging Learning Ecologies of Phd E-Researchers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Verarbeitung Emotionaler Objekte Bei Borderline-Patientinnen: Eine Untersuchung Mit Ereigniskorrelierten Potentialen (EKP)

Klinik für Psychatrie und Psychotherapie III Universitätsklinikum Ulm Prof. Dr. Dr. Manfred Spitzer Ärztlicher Direktor Die Verarbeitung emotionaler Objekte bei Borderline-Patientinnen: Eine Untersuchung mit ereigniskorrelierten Potentialen (EKP) Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Medizin der Medizinischen Fakultät der Universität Ulm von Ute Neff Bad Saulgau 2018 Amtierender Dekan: Prof. Thomas Wirth 1. Berichterstatter: Prof. Carlos Schönfeld-Lecuona 2. Berichterstatter: Prof. Christiane Waller Tag der Promotion: 16. November 2018 Teile dieser Dissertation wurden bereits im folgenden Fachartikel veröffentlicht: Kiefer M, Neff U, Schmid MM, Spitzer M, Connemann BJ, Schönfeld-Lecuona C: Brain activity to transitional objects in patients with borderline personality disorder. Scientific Reports 7(1):13121 (2017) Inhaltsverzeichnis AbkürzungsverzeichnisVI 1 Einleitung1 1.1 Borderline-Persönlichkeitsstörung . .1 1.2 Bindungsverhalten . .7 1.2.1 Bindungstheorie . .7 1.2.2 Bindungsverhalten bei Borderline-Persönlichkeitsstörung . 10 1.3 Transitionale und emotionale Objekte . 12 1.3.1 Das transitionale Objekt . 12 1.3.2 Emotionale Objekte bei Erwachsenen . 13 1.3.3 Borderline-Patienten und emotionale Objekte . 14 1.4 Grundlagen der Elektroenzephalographie und ereigniskorrelierter Potentiale 15 1.5 EKP auf emotionale Objekte . 19 1.6 Ziel der Studie . 20 1.7 Hypothesen . 21 2 Material und Methoden 23 2.1 Stichprobenbeschreibung . 23 2.1.1 Probanden . 23 2.1.2 Ein- und Ausschlusskriterien . 24 2.1.3 Fragebögen zur Erfassung der Psychopathologie . 26 2.2 Stimuli . 30 2.3 Experiment zur Erkennung emotionaler Objekte . 31 2.4 Allgemeiner Ablauf der Studie . 34 2.5 EEG-Aufzeichnung und EKP-Analyse . 34 IV Inhaltsverzeichnis 2.6 Statistische Analyse . 36 3 Ergebnisse 40 3.1 Bewertung der Stofftiere . -

Interculturalism, Intermediality and the Trope of Testimony

“Alla människor har sin berättelse”: Interculturalism, Intermediality and the Trope of Testimony in Novels by Ekman, Ørstavik and Petersen By Suzanne Brook Martin A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Linda Rugg, Chair Professor John Lindow Professor Hertha D. Sweet Wong Professor Troy Storfjell Fall 2010 Abstract “Alla människor har sin berättelse”: Interculturalism, Intermediality and the Trope of Testimony in Novels by Ekman, Ørstavik and Petersen by Suzanne Brook Martin Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Rugg, Chair This study focuses on Kerstin Ekman’s Vargskinnet trilogy (1999-2003), Hanne Ørstavik’s Presten (2004) and Martin Petersen’s Indtoget i Kautokeino (2004). The premise of this dissertation is that these novels provide a basis for investigating a subcategory of witness literature called witness fiction, which employs topoi of witness literature within a framework of explicitly fictional writing. Witness literature of all types relies on the experience of trauma by an individual or group. This project investigates the trauma of oppression of an indigenous group, the Sami, as represented in fiction by members of majority cultures that are implicated in that oppression. The characters through which the oppressed position is reflected are borderline figures dealing with the social and political effects of cultural difference, and the texts approach witnessing with varying degrees of self-awareness in terms of the complicated questions of ethics of representation. The trauma that is evident in my chosen texts stems from interactions between Sami and non-Sami communities, and I discuss the portrayal of interculturalism within these texts. -

HOT MESS 2Nd Draft.Fdr

HOT MESS by Jenni Ross Based on the novel, "THE HEARTBREAKERS" By Pamela Wells Second Draft 12/16/09 Goldsmith-Thomas Productions 239 Central Park West, Suite 6A New York, NY 10024 (212) 243-4147 OVER BLACK WE HEAR THE INTRO TO “LITTLE GREEN BAG” BY THE GEORGE BAKER SELECTION (ICONIC INTRODUCTION TO RESERVOIR DOGS). COLD OPEN: EXT. ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PLAYGROUND - DAY/FLASHBACK Four, eleven year old girls, strut confidently across the playground wearing sunglasses, a’la Reservoir Dogs. Other kids move out of their way. BEGIN TITLE SEQUENCE OVER MONTAGE: The four girls come to the aid of another kid being bullied by an older boy on the playground; they TP someone’s house by the light of the moon, laughing uncontrollably; they throw their hands high in the air on a roller coaster, screaming; they start a food fight in the cafeteria and are hauled into detention; the girls play kickball and kick ass. Kelly tags a boy with the ball as she slides onto the base. ALEXIA (V.O.) Welcome to my halcyon days. A simpler time when math homework didn’t require a calculator and your underwear still covered your ass. They raise their hands in class, unashamed that they know the answer. ALEXIA (V.O.) (CONT’D) Back then my friends and I were on top of the pre-pubescent world. We were happy to be ourselves and no amount of Britney Spears videos or American Apparel ads could convince us otherwise. The girls walk by a large print ad for Guess Jeans - Raven zips back into the shot and defaces the model by “crossing her eyes” with a Sharpie. -

How Urban Farming Initiatives Are Changing the Policy Regime in Amsterdam

Ticket to paradise or how I learned to stop worrying and love the transition: How urban farming initiatives are changing the policy regime in Amsterdam Research design Name: John-Luca de Vries Studentnumber: 10762779 Datum: July 6th, 2018 Word count: 15821 Supervisors: John Grin & Anna Aalten Introduction The stability of urban food systems depends on a properly functioning global market, open trade routes, affordable energy and stable weather conditions, factors which will likely become less secure under the influence of climate change and ecological degradation (Fraser et al., 2005)(Moore, 2015). Urban Agriculture (UA) is an urban food production practice attaining more resilience in urban food systems by making cities less reliant on the import of food and the export of waste, more self-sufficient in food production, and by bringing a range of environmental and health benefits to the urban population (Bell & Cerulli, 2012). However, many structural barriers are still in place that make it difficult for the mainly small-scale community gardening initiatives to grow into a proper alternative food network. A lack of access to land, labor, water, seeds and technical support, or restrictive regulations and public health laws may act as barriers preventing the transformation of small-scale community gardening initiatives into a viable alternative urban food production system (Mourque, 2000)(Bell & Cerulli, 2012)(Roemers, 2014). In the Netherlands and Amsterdam in particular we can see that policy makers have started accommodating urban farmers by offering subsidies and giving the phenomenon more attention (Metaal et al., 2013)(Agenda Groen, 2015). Changing policy is central to reduce barriers that urban farmers run into because preconceptions of city planners and managers make it more difficult to institutionalize and expand farming in the city (Mourque, 2000, p. -

Clotel 184) with the Speed of a Bird, Having Passed the Avenue, She Began to Gain, and Presently She Was Upon the Long Bridge

European journal of American studies 15-2 | 2020 Summer 2020 Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/15701 DOI : 10.4000/ejas.15701 ISSN : 1991-9336 Éditeur European Association for American Studies Référence électronique European journal of American studies, 15-2 | 2020, « Summer 2020 » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 23 juin 2020, consulté le 08 juillet 2021. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/15701 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/ejas.15701 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 8 juillet 2021. European Journal of American studies 1 SOMMAIRE What on Earth! Slated Globes, School Geography and Imperial Pedagogy Mahshid Mayar Homecomings: Black Women’s Mobility in Early African American Fiction Anna Pochmara Hollywood’s Depiction of Italian American Servicemen During the Italian Campaign of World War II Matteo Pretelli “Being an Instance of the Norm”: Women, Surveillance and Guilt in Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road Vavotici Francesca Complicating American Manhood: Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time and the Feminist Utopia as a Site for Transforming Masculinities Michael Pitts Beyond Determinism: Geography of Jewishness in Nathan Englander’s “Sister Hills” and Michael Chabon’s The Yiddish Policemen’s Union Filip Boratyn Rummaging Through the Ashes: 9/11 American Poetry and the Transcultural Counterwitness Matthew Moran “Challenging Borders: Susanna Kaysen’s Girl, Interrupted as a Subversive Disability Memoir” Pascale Antolin Un/Seeing Campus Carry: Experiencing Gun Culture in Texas Benita Heiskanen -

Michail Kontopodis (Email: [email protected])

Fachbereich Erziehungswissenschaft und Psychologie Freie Universität Berlin F A B R I C A T I N G H U M A N D E V E L O P M E N T THE DYNAMICS OF ‘ORDERING’ AND ‘OTHERING’ IN AN EXPERIMENTAL SECONDARY SCHOOL (HAUPTSCHULE) Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt von Michail Kontopodis (Email: [email protected]) Fabricating Human Development Erstgutachter (First Supervisor): Prof. Dr. Martin Hildebrand-Nilshon, Arbeitsbereich Entwicklungs-psychologie, Fachbereich Erziehungswissenschaft und Psychologie, Freie Universität Berlin Zweitgutachter (Second Supervisor): Prof. Dr. Bernd Fichtner, Fachbereich 2: Erziehungswissenschaften, Universität Siegen Ort und Zeit der Disputation (Time and Place of Disputation): Berlin, 2. Juli 2007. 2 Contents Acknowledgements p. 4 Opening Intro Processing time: the dynamics of development as becoming p. 10 Map 1 Contexts and methodologies p. 38 1st Movement Map 2 Development as a technology of the self p. 57 Map 3 Communicating human development: the interactional organization of the self and of (non-) development p. 73 2nd Movement Map 4 Materializing time and institutionalizing human development p. 99 Map 5 Ordering and stabilizing human development p. 118 Map 6 Contrasting the School for Individual Learning-in-Practice with the Freedom Writers’ project p. 143 Finale Unlimiting human development p. 163 References p. 169 Appentix: Transcription and Coding of Oral Data p. 196 Disclaimer to Dissertation p. 198 To my parents Chrysoula & Jiannis, and to my brothers Manos & Dimitris And with respect and solidarity to Aanke, Barbara, Chriss, David, Florian, Nicola, Reinhard, Sélale, Wienfried and all the other teachers and students of the #School for Individual Learning-in-Practice# (name changed) Cover Picture: Composition of M.K.: a collage of two pictures drawn by students, a CV (see p. -

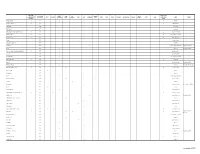

Master Streaming List 06112021

Heat Index Personal Star IMDb Rating Netflix Prime PBS Peacock/ IMDb 5=Intense/Dark Acorn Brit Box Hulu HBO Sundance Starz SHO ROKU Cinemax BBC America Disney+ EPIX USA Rating 1 to 5 Genre Notes (Out of 10) Streaming Video Passport NBC Freedive 1="Cozie" (best) Breaking Bad 5 9.5 ● 5 drama Game of Thrones 5 9.5 ● 5 action/thriller Chernobyl 9.4 ● docudrama The Wire 9.3 ● policing Sherlock (Benedict Cumberbatch) 3 9.2 ● ● 4 private detective The Sopranos 5 9.2 ● 5 heists/organized crme True Detective 5 9.0 ● 5 police detective Fargo 8.9 ● crime drama Only Fools & Horses 8.9 ● comedy Aranyelet 8.8 ● general mystery/crime English subtitles Dark 8.8 ● mystery English subtitles House of Cards (Netflix production) 4 8.8 ● political satire Narcos 8.8 ● organized crime Peaky Blinders 8.8 ● heists/organized crime The Sandbaggers 3 8.8 ● 4 espionage Umbre 8.8 ● organized crime English subtitles Better Call Saul 8.7 ● drama Breaking Bad prequel Brideshead Revisited 2 8.7 ● ● 5 period drama Danger UXB 8.7 ● drama Deadwood 8.7 ● drama Dexter 8.7 ● ● general mystery/crime Downton Abbey 1 8.7 ● ● period drama Fleabag 8.7 ● comedy Gomorrah 8.7 ● organized crime Italian with subtitles Rake 8.7 ● 2 legal Sacred Games 8.7 ● police detective Sherlock Holmes (Jeremy Brett) 2 8.7 ● 5 private detective The Bureau 8.7 ● police detective English subtitles The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel 8.7 ● drama The Shield 8.7 ● police detective The Thick of It 8.7 ● political drama Westworld 8.7 ● sci fi Poirot (David Suchet series) 1 8.6 ● ● 5 private detective Inspector Morse -

My Many Selves

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2006 My Many Selves Wayne C. Booth Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Cultural History Commons Recommended Citation Booth, W. C. (2006). My many selves: The quest for a plausible harmony. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. My Many Selves The Quest for a Plausible Harmony Wayne C. Booth My Many Selves My Many Selves The Quest for a Plausible Harmony Wayne C. Booth Utah State University Press Logan, Utah Copyright © 2006 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322–7800 www.usu.edu/usupreses Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Booth, Wayne C. My many selves : the quest for a plausible harmony / Wayne C. Booth. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-87421-633-8 (hardcover : alk. paper)-- ISBN 0-87421-631-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 0-87421-535-8 (e-book) 1. Booth, Wayne C. 2. Critics--United States--Biography. 3. Mormons--United States-- Biography. I. Title. PN75.B62A3 2006 809--dc22 2005031116 It has amazed me that the most incongruous traits should exist in the same person and for all that yield a plausible harmony.1 I have often asked myself how characteristics, seemingly irreconcilable, can exist in the same person. -

The Imaginative Nature National Council of Teachers of En

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 404 675 CS 215 781 AUTHOR Pugh, Sharon L.; And Others TITLE Metaphorical Ways of Knowing: The Imaginative Nature of Thought and Expression. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-3151-4 PUB DATE 97 NOTE 225p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (NCTE Stock No. 31514-3050: $12.95 members, $16.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.) (120) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; *English; *Imagination; Interdisciplinary Approach; Intermediate Grades; Language Arts; *Language Role; *Metaphors; *Multicultural Education; Rhetoric; Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS *Metaphorical Thought ABSTRACT This book explores the subject of metaphor, using the imagery of cartography to set a course. It explores the creative aspects of thinking and learning through literature, writing, and word play, drawing connections between English and other content areas. Theory and practical applications meet in the book, linking activities and resources to current classroom concerns--to multiculturalism, imagination in reading and writing, critical thinking, and expanding language experiences. The first part of the book examines the uses of metaphor in constructing meaning. The second part takes up issues related to multiple perspectives--using metaphors to experience other lives, and exploring cultures through traditions. The third part of the book is devoted to a consideration of the history and current status of the English language and focuses on using cross-cultural stories in the English classroom, offering a number of resources for teaching multicultural literature in English. The fourth part examines the sensory Ixperience of metaphors by seeing, hearing, tasting, smelling, and touching with the imagination. -

A Companion to Michael Haneke

A Companion to Michael Haneke Edited by Roy Grundmann A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication A Companion to Michael Haneke Wiley-Blackwell Companions to Film Directors The Wiley-Blackwell Companions to Film Directors survey key directors whose work together constitutes what we refer to as the Hollywood and world cinema canons. Whether Haneke or Hitchcock, Bigelow or Bergmann, Capra or the Coen brothers, each volume, comprised of 25 or more newly commissioned essays writ- ten by leading experts, explores a canonical, contemporary and/or controversial auteur in a sophisticated, authoritative, and multi-dimensional capacity. Individual volumes interrogate any number of subjects – the director’s oeuvre; dominant themes, well-known, worthy, and under-rated films; stars, collaborators, and key influences; reception, reputation, and above all, the director’s intellectual currency in the scholarly world. 1 A Companion to Michael Haneke, edited by Roy Grundmann 2 A Companion to Alfred Hitchcock, edited by Leland Poague and Thomas Leitch 3 A Companion to Rainer Fassbinder, edited by Brigitte Peucker 4 A Companion to Werner Herzog, edited by Brad Prager 5 A Companion to François Truffaut, edited by Dudley Andrew and Anne Gillian 6 A Companion to Pedro Almódovar, edited by Marvin D’Lugo and Kathleen Vernon 7 A Companion to John Ford, edited by Peter Lehman 8 A Companion to Jean Renoir, edited by Alistair Phillips and Ginette Vincendeau 9 A Companion to Louis Buñuel, edited by Robert Stone and Julian Daniel Gutierrez-Albilla 10 A Companion to Martin Scorsese, edited by Peter J. Bailey and Sam B. Girgus 11 A Companion to Woody Allen, edited by Aaron Baker A Companion to Michael Haneke Edited by Roy Grundmann A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication This edition first published 2010 © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd except for editorial material and organization © 2010 Roy Grundmann Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. -

April 15 - 21, 2018

APRIL 15 - 21, 2018 staradvertiser.com COUNTRY SHINES The best and brightest in country music hit the strip for the 53rd Academy of Country Music Awards. The iconic Reba McEntire hosts this year’s ceremony for the 15th time, and is also up for Female Vocalist of the Year — her 16th nomination in the category. Broadcast live from Las Vegas’ MGM Grand Garden Arena, the night celebrates all of country music’s fi nest, from veteran superstars to fresh, emerging talents. Airing Sunday, April 15, on CBS. Join host, Lyla Berg as she sits down with guests Meet the NEW SHOW who share their work on moving our community forward. WEDNESDAY! people SPECIAL GUESTS INCLUDE: John Wood, Director, U.S. Pacific Command and places Daria Loy-Goto, Complaints and Enforcement Officer, that make Regulated Industries Complaints Office (RICO) 1st & 3rd Hawai‘i Jim Howe, Director, Honolulu Emergency Services Department Wednesday of the Month, Kuuipo Kumukahi, Artistic Director, Hawaiian Music Hall of Fame 6:30 pm | Channel 53 olelo.org special. Tyler Kurashige, Director of Program Operations, Big Brothers Big Sisters ON THE COVER | 53RD ACADEMY OF COUNTRY MUSIC AWARDS Pro host Reba McEntire returns to host the 53rd boys dominate, so it’s coming around. I have Rebecca Romijn (“X-Men,” 2000) and Olympic Academy of Country Music Awards faith.” Nominated in the category this year are athlete Lindsey Vonn. Jason Aldean, Garth Brooks, Luke Bryan, Chris ACM Award-nominated artist Bentley put Stapleton and Keith Urban. out a call to fans earlier this month, looking By Sarah Passingham Her disappointment is understandable, TV Media to make his performance special. -

Expert Witnesses and International War Crimes Trials: Making Sense of Large-Scale Violence in Rwanda

Springer Series in Transitional Justice Volume 8 Series Editor Olivera Simic, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/11233 Dubravka Zarkov • Marlies Glasius Editors Narratives of Justice In and Out of the Courtroom Former Yugoslavia and Beyond 2123 Editors Dubravka Zarkov Marlies Glasius International Institute of Social Studies/EUR University of Amsterdam The Hague Amsterdam The Netherlands The Netherlands ISBN 978-3-319-04056-1 ISBN 978-3-319-04057-8 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-04057-8 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2014932418 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Permissions for use may be obtained through RightsLink at the Copyright Clearance Center. Violations are liable to prosecution under the respective Copyright Law.