The Legislative Process in Wisconsin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disability Vote Coalition Updates

1-844-DIS-VOTE www.disabilityvote.org Date: March 23, 2021 To: BPDD Board From:Barbara Beckert, Disability Rights Wisconsin, [email protected] Jenny Neugart, BPDD, [email protected] Re: Wisconsin Disability Vote Coalition Update This has been a busy time for the Disability Vote Coalition (DVC) with elections occurring in February and April and consideration of policy changes that would have a significant impact on many voters with disabilities and older adults. We invite all board members to join our email list by signing up at https://disabilityvote.org/ If you are on Facebook, please “like” us, invite your friends, and share our posts. We also ask for your help to educate policy makers about the importance of voting rights and policies that are accessible and inclusive of voters with disabilities. As discussed in this report, new bills have been introduced that may make it harder for many people with disabilities and older adults to vote. This document summarizes DVC priorities and activities since the last report. 2021 Spring Elections and Special Legislative Elections With important election held on February 16th and coming up April 6th, the Coalition has developed new resources, provided trainings, and held a candidate forum for State Superintendent of Public Instruction candidates. We encourage board members to follow us on Facebook and to promote Coalition resources and the DRW Voter Hotline. Please consider yourself a voting ambassador! The Wisconsin Disability Vote Coalition is a project of Wisconsin Board for People with Developmental Disabilities and Disability Rights Wisconsin New and updated DVC Fact Sheets for the Spring Elections The DVC developed new fact sheets for the Spring election and updated current fact sheets. -

March/April 2021

MARCH/APRIL 2021 WBA Awards Gala Update on Page 3! Sen. Smith to visit Summer Conference CHAIR’S COLUMN The President and CEO of the National Association Positivity important as end to pandemic nears of Broadcasters is coming to the WBA Summer Con- ference in August. Is it spring? As I write this, we are experiencing mild weather and many parts of Wisconsin have hit 50 Senator Gordon Smith will be the keynote speaker degrees. After the bitter cold temperatures we had in on Aug. 26, the second day of the conference at the February how can a person not think of spring. Blue Harbor Resort in Sheboygan. Sue Keenom, Senior Vice President, State, Interna- We are steadily showing signs of ending the COVID Smith tional, and Board Relations for NAB, will be joining pandemic. There was a recent article from Dr. Marty him. Makary of John Hopkins University that read the U.S. could reach herd immunity early in the second “We’re thrilled to have Sen. Smith join us as we celebrate the 70th Chris Bernier quarter this year and may already be reaching it. He year of the WBA,” said WBA President and CEO Michelle Vetterkind. WBA Chair states that COVID cases have dropped 77 percent in “This will be our first opportunity to gather since the pandemic and the Untied States in the last six weeks. We try to provide positive facts a perfect occasion to celebrate.” like this to our staff, particularly our salespeople. When making sales Smith joined the National Association of Broadcasters as president calls, I want our people to be positive. -

Wisconsineye Partners with Milwaukee Journal Sentinel & Gannett Wisconsin to Provide Extensive Coverage of 2016 Wisconsin Election Campaigns

WISCONSINEYE PARTNERS WITH MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL & GANNETT WISCONSIN TO PROVIDE EXTENSIVE COVERAGE OF 2016 WISCONSIN ELECTION CAMPAIGNS NEWS NETWORKS CO-LAUNCHING A VIDEO PLAYER HOSTING HUNDREDS OF CANDIDATE INTERVIEWS 8/1/2016 Contact: Kristen Colgin Phone: 608.316.6850 Email: [email protected] Madison, WI -- WisconsinEye, an evenhanded nonprofit news network, is launching a free video player providing the state’s most extensive coverage of Wisconsin legislative races. The Campaign 2016 video player will contain an array of campaign events and interviews at the state and federal levels. Viewers will also have access to hundreds of in-depth interviews with candidates for the Wisconsin State Senate and Assembly, in both the primary and general elections. All WisconsinEye interviews are conducted by WisconsinEye senior producer Steve Walters, a veteran State Capitol journalist. Steve was recognized in 2013 as "Wisconsin Journalist of the Year" by the Milwaukee Press Club, the first time an individual rather than a broadcast or news entity received the club's highest honor. In addition to candidate interviews, news conferences, and interviews with campaign insiders and analysts will round out the coverage between August and the inauguration of election winners in January 2017. Campaign 2016 is a partnership between WisconsinEye and the Gannett family of online news sites in Wisconsin, including its flagship, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. The video player will host an array of campaign events and interviews at the state and federal levels. All WisconsinEye election coverage will be simultaneously available at wiseye.org and the 11 Gannett online sites. “The goal is to create a big, wide open window into these elections,” said WisconsinEye president Jon Henkes. -

Success Highlights Importance of Member Involvement

MARCH/APRIL 2020 CHAIR’S COLUMN Success highlights importance of member involvement The Wisconsin Broadcasters Association is regarded If you need background on important issues for one of these as one of the best state broadcasting association in meetings, don’t hesitate to contact the WBA office for support. Also, the country. This is according to Sen. Gordon Smith, when we have these local meetings, we should constantly remind the President and CEO of the National Association the elected officials of our value, how we are involved in virtually of Broadcasters. everything that happens in our communities, and the millions of During our recently completed legislative trip to dollars that Wisconsin Broadcasters help raise for their communities Washington DC, we also heard this from many every year. leaders of other state associations. The WBA is so We recently celebrated another legislative victory in the state Chris Bernier highly regarded because of the dedicated work by when Governor Evers signed into law the bill regarding the use of WBA Chair our President, Michelle Vetterkind, and the staff, but law enforcement body cameras. This was one of our talking points equally as important, is our membership! during State Legislative Day and in local meetings, plus the phone Our membership’s relationships with our elected officials are one of blitz that many of you participated in just before the vote. This is most significant things we can do as local broadcasters. Calling on another triumph in a long list of successes we have had thanks to them during State Legislative Day and in DC is very important. -

Summer Vacation Collaborative Imperative

October 2007 l Number 66 McIntyre Library l www.uwec.edu/library/aboutus/offtheshelf/ IN THIS ISSUE: NEW @YOUR LIBRARY® University Archives Goes Digital. 2 Nursing Learning Resources. .2 In Memory of Carol Lonning. .2 Check Out These Movies. .2 How I Spent My AROUND THE LIBRARY Children’s Events. 3 Distance Education Services . 4 Summer Vacation Collaborative Imperative . 5 From the by John Pollitz, [email protected] Like many librarians I came to the profes- Director’s Desk. 6 sion as a second career. I have been a librari- an for 17 years, having received my MLS from VIRTUAL LIBRARY This summer, my wife, Aracely, and I the University of Iowa in 1990. Throughout my Gale Virtual Reference. .7 watched all of our worldly possessions get packed career I have focused on advancing libraries WisconsinEye . 8 in a huge truck. We loaded up our two cars with technologically, and teaching students to think UW Digital RSS. 8 our cat, Cupcake, and all of the things we could critically about information and become more Databases and not live without and took four days to drive across effective users of all the information that tech- Titles Added . .9 country from Corvallis, Oregon, to Eau Claire. nology makes available to them. I have an MA Education Research Complete . .9 This spring I was hired to be the new director of in Latin American history from the University libraries at UW-Eau Claire. I spent the late spring of Denver and got my BA in history and edu- IN BRIEF and summer preparing for the move, packing up cation from Southern Illinois University. -

2020 Milwaukee Press Club

MILWAUKEE PRESS CLUB 2 0 2 0 ON DEADLINE? CALL ONE OF AMERICA’S TOP RESEARCH UNIVERSITIES Content 2 President’s Letter Special thanks to Sponsorship Committee: 3 Milwaukee’s 174th Lori Richards, Mueller Birthday: Unconventional Communications, LLC Milwaukee Executive Director 4 MPC Endowment Joette Richards, 262-894-2224 5 MPC Awards for Once A Year has been produced Excellence in Wisconsin annually by the Milwaukee Journalism Press Club since 1886. All of the issues are archived at the Golda 14 Milwaukee Press Club Meir Library of the University of Board of Governors Wisconsin-Milwaukee and are used frequently for historical 15 2020 Press Club research. Members Press Club 16 Press Club Honors Meeting Place With hundreds of faculty members in a BACK COVER Newsroom Pub, 137 E. Wells St., Thanks to our Sponsors wide range of disciplines – from public Milwaukee, WI 53202 health to politics, economics to education, Editor milwaukeepressclub.org Claire Hanan – we have the expertise you need. Mailing Address PO Box 176 Designer North Prairie, WI 53153-0176 Contact media-services-team@edu. Kathryn Lavey MPC and MPC Endowment Ltd. thank this year’s independent panel of contest judges, active journalists from press clubs throughout the U.S., including statewide clubs in Alaska, Florida, Idaho and Michigan and metro-area clubs in Cleveland, Dallas, Houston, Los Angeles, New Orleans, Pittsburgh, San Diego, San Francisco and Syracuse. A special thanks to Maryann Lazarski, Joette Richards and the MPC contest committee for their oversight of our contest. Each year, the Milwaukee UWM consumer marketing expert Purush Papatla (right), co-director of the Northwestern Mutual Data Science Institute. -

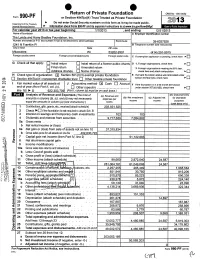

0 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

• O Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation III. Do not enter Social 2013 Department of the Treasury Security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Internal Revenue Service No Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs. ov/form99( For calendar year 2013 or tax year beginnin 3 , and 12/31/201 Name of foundation A Employer Identification number The Lvnde and Harry Bradley Foundation. Inc. Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite 39-6037928 1241 N Franklin PI B Telephone number (see instructions) City or town State ZIP code Milwaukee WI 53202-2901 414 291-9915 Foreign country name Foreign province/state/county Foreign postal code q C If exemption application is pending, check here ► G Check all that apply: q q D q Initial return Initial return of a former public charity 1. Foreign organizations, check here ► q q Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, q q q Address change Name chanqe check here and attach computation ► H Check type of organization: Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated under q q Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust q Other taxable private foundation section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► 0 CV Fair market q q I value of all assets at J Accountinq method- Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination end of year (from Part ll, col. -

Capitol Correspondents (7/14/16)

Capitol Correspondents (7/14/16) Printed Press Appleton Post‐Crescent 920‐993‐1000 Wisconsin Catholic Newspapers General [email protected] Kim Wadas 257‐0004 [email protected] The Associated Press 255‐3679 Scott Bauer (c) 658‐7131 The Wisconsin State Journal [email protected] Matt Defour (O) 252‐6144 (C) 338‐6329 @sbauerAP [email protected] Todd Richmond (c) 658‐1120 @WSJMattD4 [email protected] Mark Sommerhauser (O) 252‐6122 (C) 286‐0394 @trichmond1 [email protected] @msommerhauser The Badger Herald 257‐4712 Molly Beck (O) 252‐6135 (C) 287‐8412 Editor in Chief (ext. 101) [email protected] [email protected] @MollyBeck The Capital Times 252‐6429 Jessica Opoien (o) 252‐6436 (c) 920‐883‐5328 Wispolitics.com 441‐8418 [email protected] @jessieopie JR Ross, Editor Katelyn Ferral 252‐6462 [email protected] [email protected] @katelynferral @jrrosswrites Chris Thompson, The Daily Reporter/Wisconsin Law Journal 616‐9820 [email protected] Erika Strebel 630‐689‐8936 @WisPoliChris [email protected] Polo Rocha, WisBuisness.com Editor @erikastrebel [email protected] @polorocha18 Green Bay Press‐Gazette 1‐800‐510‐5353 Colin Schmies, Sales and Marketing [email protected] Isthmus Judith Davidoff 251‐5627 (ext.142) Radio [email protected] WIBA Radio (Madison) @JudyDavidoff [email protected] Robin Colbert 271‐6397 The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel 258‐2262/258‐2274 [email protected] Jason Stein (c) 338‐8241 (correspondent for WTMJ‐Milwaukee and Wisconsin Radio [email protected] -

Go Dumpster Diving at WISC-TV Addressing the New World of DTV Multichannel Audio WISC-TV Is Cleaning out Its Storage Building

Society of Broadcast Engineers Newsletter Chapter 24 July 2007 Madison, Wisconsin In this Issue Amateur Radio News ............ 3 be eco-friendly FCC Meeting ........................ 4 From the Chair ...................... 5 find hidden treasures WisconsinEye ........................ 6 Next Meeting Thursday, July 17 go dumpster diving at WISC-TV Addressing the New World of DTV Multichannel Audio WISC-TV is cleaning out its storage building. In an effort Steve Strassberg, Strassberg Associates, the to keep excess material out of the landfill, WISC is inviting distributor and spokesman for the Linear Acoustic you to attend a dumpster diving party on Saturday, July 21 company, will present an informative program from 1 to 4 p.m. All items are free, as is and must be removed on DTV audio. It has been over 10 years since by the end of the day. Manuals and extender cards will be ATSC officially published the standards describing the audio system for digital television. With the available for most items. end of analog over-the-air rapidly approaching, You’ll find an eclectic assortment of audio, video, how is audio today? Many would agree that it is computer and RF gear, along with racks and various cable far less consistent and far more prone to level and scrap. The collected material will be on display inside the Old image shifts than ever before. Seemingly every Transmitter Building at the south edge of the front parking network handles the audio side of DTV in a dif- lot, rain or shine. ferent manner, the results audibly amplify these differences. Consumers are now presented with Contact Steve Paugh at WISC-TV, 608-277-5139, or a large number of audio sources, none of which [email protected] for more information. -

Wisconsin Broadcaster March April 2018 3/5/2018 12:00 PM Page 1

wisconsin broadcaster_march april 2018 3/5/2018 12:00 PM Page 1 MARCH/APRIL 2018 SAVE THE DATE Awards Gala CHAIR’S COLUMN Wisconsin MayBroadcasters 5, 2018 Association Get involved in the WBA It’s an honor to represent you this year colleagues. Your competitors. If you believe as I do, that our future is bright but comes with all manner of new challenges and opportunities, as your WBA Chair! then I ask you to ENGAGE with your state association in a big way. I don’t have any magical formulas to share with you for prosperity or success, but I will use my first column to • Come to our winter and summer conferences (…and ask one thing of you and your staff this year: ENGAGE bring a bunch of your people with you). with your WBA. Perhaps like you, I spent some of my • Attend the many workshops and seminars WBA provides. Steve Wexler early years as a Wisconsin broadcaster vaguely aware • Offer to serve on our board of directors or on one of our WBA Chair of the work being done by the Wisconsin Broadcasters Association. I attended some award galas and dutifully committees. showed up for EEO seminars so I could claim license credit. Doug Kiel, • Support our primary fundraising mechanism, the himself a former WBA Chair and one of Wisconsin’s own broadcast NSA/PEP program, by running the spots on your stations treasures, encouraged me to get more involved. It didn’t take long for in strong rotations. me to better appreciate the work WBA (and the WBA Foundation) was • Help us influence policy and law by lobbying with us on doing on our behalf. -

New DTV Bill Introduced Amateur Radio News

Society of Broadcast Engineers Newsletter Chapter 24 Madison, Wisconsin February 2007 In this Issue Minutes .................................. 2 New DTV Bill Introduced Amateur Radio News ............ 3 Bill requires consumer education FCC Rulemakings ................. 5 Unlicensed Devices ............... 5 about switch to digital broadcasting SBE Notes ............................. 6 By Tom Smith Next Meeting Thursday, Feb. 15 RF Path Predictions & NOTICE This television has only an analog tuner and will require a Nominations converter box after February 17, 2009, to receive SBE member Tom Weeden, over-the-air broadcasts with an antenna because of the WJ9H, will demonstrate how to nation’s transition to digital broadcasting. The TV should con- predict and analyze RF paths tinue to work as before with cable and satellite TV services, using a freeware program, gaming consoles, VCRs, DVD players and similar products. RadioMobile, written by a Cana- For more information, call the Federal Communications dian amateur radio operator. Commission at 1-888-225-5322 (TTY: 1-888-835-5322) or visit Using public domain databases the Commission’s digital television Web site at www.dtv.gov. you can predict your coverage area. Tom will show you how to Proposed wording of Digital Television use it for broadcast applications Consumer Act of 2007 notice and the originally intended amateur applications. Parking is limited at the WMTV studios A new DTV consumer education broadcasts with an antenna because of and we are not to park in the reserved bill has been introduced in the House the nation’s transition to digital broad- spaces normally occupied by the news vehicles. Park on Forward Drive if all of of Representatives by Joe Barton (R- casting. -

The Excellence in Broadcasting Awards

WBA is proud to announce… Awards For Excellence Winners Television Award Winners BEST USE OF SPORTS VIDEO Large Market Television 1st Place: WISN-TV, Playoff Battle SPOT NEWS nd 2 Place: WDJT-TV, Trash Talk st 1 Place: WTMJ-TV, Capitol Chaos 3rd Place: WITI-TV, Tough Mudder 2nd Place: WISN-TV, Germantown Crash rd WEATHERCAST 3 Place: WISN-TV, Bluff Collapse 1st Place: WISN-TV, Weather Watch 12, 2/1/2011 MORNING NEWSCAST nd 2 Place: WTMJ-TV, Brian Gotter 1st Place: WISN-TV, Budget Battle AM 3rd Place: WITI-TV, Vince Condella Composite 2nd Place: WITI-TV, Fox 6 WakeUp News - 2/2/2011 rd SIGNIFICANT COMMUNITY IMPACT 3 Place: WTMJ-TV, The Big Blizzard 1st Place: WITI-TV, Prostate Cancer Screening EVENING NEWSCAST nd 2 Place: WISN-TV, Made in Wisconsin 1st Place: WISN-TV, Collective Bargaining 3rd Place: WTMJ-TV, Community Baby Shower 2011 Showdown nd SPECIALTY PROGRAMMING 2 Place: WISN-TV, Blizzard 2011 rd 1st Place: WITI-TV, Season of Giving 3 Place: WTMJ-TV, TODAY'S TMJ4 Live at 10 nd 2 Place: WITI-TV, Fox 6 Blitz NEWS WRITING rd 3 Place: WISN-TV, Season to Celebrate 1st Place: WISN-TV, Dog Tags Returned nd EDITORIAL/COMMENTARY 2 Place: WITI-TV, Autism Dog Helper st rd 1 Place: WITI-TV, Ted's Take #2 3 Place: WITI-TV, Honor Flight nd 2 Place: WITI-TV, Ted's Take #1 HARD NEWS/INVESTIGATIVE 3rd Place: WTMJ-TV, What's Hot st 1 Place: WISN TV, Sex Offender Loophole nd PROMOTIONAL ANNOUNCEMENT 2 Place: WISN TV, Sleeping Dispatcher 1st Place: WDJT-TV, Just 10 Minutes 2011 Campaign 3rd Place: WTMJ TV, Big Bonuses nd 2 Place: WISN-TV, Experience