Catherine Riccio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'équipe Des Scénaristes De Lost Comme Un Auteur Pluriel Ou Quelques Propositions Méthodologiques Pour Analyser L'auctorialité Des Séries Télévisées

Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées Quentin Fischer To cite this version: Quentin Fischer. Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-02368575 HAL Id: dumas-02368575 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02368575 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ RENNES 2 Master Recherche ELECTRA – CELLAM Lost in serial television authorship : L'équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l'auctorialité des séries télévisées Mémoire de Recherche Discipline : Littératures comparées Présenté et soutenu par Quentin FISCHER en septembre 2017 Directeurs de recherche : Jean Cléder et Charline Pluvinet 1 « Créer une série, c'est d'abord imaginer son histoire, se réunir avec des auteurs, la coucher sur le papier. Puis accepter de lâcher prise, de la laisser vivre une deuxième vie. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Kierkegaard and Byron: Disability, Irony, and the Undead

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2015 Kierkegaard And Byron: Disability, Irony, And The Undead Troy Wellington Smith University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Troy Wellington, "Kierkegaard And Byron: Disability, Irony, And The Undead" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 540. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/540 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KIERKEGAARD AND BYRON: DISABILITY, IRONY, AND THE UNDEAD A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English The University of Mississippi by TROY WELLINGTON SMITH May 2015 Copyright © 2015 by Troy Wellington Smith ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT After enumerating the implicit and explicit references to Lord Byron in the corpus of Søren Kierkegaard, chapter 1, “Kierkegaard and Byron,” provides a historical backdrop by surveying the influence of Byron and Byronism on the literary circles of Golden Age Copenhagen. Chapter 2, “Disability,” theorizes that Kierkegaard later spurned Byron as a hedonistic “cripple” because of the metonymy between him and his (i.e., Kierkegaard’s) enemy Peder Ludvig Møller. Møller was an editor at The Corsair, the disreputable satirical newspaper that mocked Kierkegaard’s disability in a series of caricatures. As a poet, critic, and eroticist, Møller was eminently Byronic, and both he and Byron had served as models for the titular character of Kierkegaard’s “The Seducer’s Diary.” Chapter 3, “Irony,” claims that Kierkegaard felt a Bloomian anxiety of Byron’s influence. -

Edward Rochester: a New Byronic Hero Marybeth Forina

Undergraduate Review Volume 10 Article 19 2014 Edward Rochester: A New Byronic Hero Marybeth Forina Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Forina, Marybeth (2014). Edward Rochester: A New Byronic Hero. Undergraduate Review, 10, 85-88. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev/vol10/iss1/19 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Copyright © 2014 Marybeth Forina Edward Rochester: A New Byronic Hero MARYBETH FORINA Marybeth Forina is a n her novel Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë established several elements that are senior who is double still components of many modern novels, including a working, plain female hero, a depiction of the hero’s childhood, and a new awareness of sexuality. majoring in Elementary Alongside these new elements, Brontë also engineered a new type of male hero Education and English Iin Edward Rochester. As Jane is written as a plain female hero with average looks, with a minor in Rochester is her plain male hero counterpart. Although Brontë depicts Rochester as a severe, yet appealing hero, embodying the characteristics associated with Byron’s Mathematics. This essay began as a heroes, she nevertheless slightly alters those characteristics. Brontë characterizes research paper in her senior seminar, Rochester as a Byronic hero, but alters his characterization through repentance to The Changing Female Hero, with Dr. create a new type of character: the repentant Byronic hero. Evelyn Pezzulich (English), and was The Byronic Hero, a character type based on Lord Byron’s own characters, is later revised under the mentorship of typically identified by unflattering albeit alluring features and an arrogant al- Dr. -

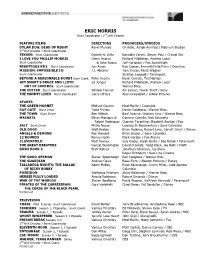

ERIC NORRIS Stunt Coordinator / 2Nd Unit Director

ERIC NORRIS Stunt Coordinator / 2nd Unit Director FEATURE FILMS DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS DYLAN DOG: DEAD OF NIGHT Kevin Munroe Gil Adler, Ashok Amritraj / Platinum Studios 2nd Unit Director / Stunt Coordinator TEKKEN Stunt Coordinator Dwight H. Little Benedict Carver, Steven Paul / Crystal Sky I LOVE YOU PHILLIP MORRIS Glenn Ficarra Richard Middleton, Andrew Lazar Stunt Coordinator & John Requa Jeff Harlacker / Fox Searchlight RIGHTEOUS KILL Stunt Coordinator Jon Avnet Rob Cowan, Emmett/Furla Films / Overture MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE III J.J. Abrams Tom Cruise, Paula Wagner Stunt Coordinator Stratton Leopold / Paramount BEYOND A REASONABLE DOUBT Stunt Coord. Peter Hyams Kevin Cornish, Ted Hartley GET SMART’S BRUCE AND LLOYD Gil Junger Richard Middleton, Andrew Lazar OUT OF CONTROL Stunt Coordinator Warner Bros. THE CUTTER Stunt Coordinator William Tannen Avi Lerner, Trevor Short / Sony THE MUMMY LIVES Stunt Coordinator Gerry O’Hara Allan Greenblatt / Global Pictures STUNTS THE GREEN HORNET Michael Gondry Neal Moritz / Columbia DUE DATE Stunt Driver Todd Phillips Daniel Goldberg / Warner Bros. THE TOWN Stunt Driver Ben Affleck Basil Iwanyk, Graham King / Warner Bros. MACHETE Ethan Maniquis & Dominic Cancilla, Rick Schwartz Robert Rodriguez Quentin Tarantino, Elizabeth Avellan / Fox SALT Stunt Driver Phillip Noyce Lorenzo Di Bonaventura / Sony Columbia OLD DOGS Walt Becker Brian Robbins, Robert Levy, Garrett Grant / Disney ANGELS & DEMONS Ron Howard Brian Grazer / Sony Columbia 12 ROUNDS Renny Harlin Mark Gordon / Fox Atomic CLOVERFIELD Matt Reeves Guy Riedel, Bryan Burke / Bad Robot / Paramount THE GREAT DEBATERS Denzel Washington David Crockett, Todd Black, Joe Roth / MGM RUSH HOUR 3 Brett Ratner Jonathan Glickman, Jay Stern Roger Birnbaum / New Line Cinema THE GOOD GERMAN Steven Soderbergh Ben Cosgrove / Warner Bros. -

Efe, Opinion Imposing Sanctions, 19PDJ058, 09-17-20.Pdf

People v. Anselm Andrew Efe. 19PDJ058. September 17, 2020. A hearing board suspended Anselm Andrew Efe (attorney registration number 38357) for one year and one day. The suspension, which runs concurrent to Efe’s suspension in case number 18DJ041, took effect on October 28, 2020. To be reinstated, Efe must prove by clear and convincing evidence that he has been rehabilitated, has complied with disciplinary orders and rules, and is fit to practice law. In a child support modification matter, Efe did not competently or diligently represent his client. He ignored disclosure and discovery requirements, and he failed to advise his client about the client’s obligations to produce complete and timely financial information. Later, when opposing counsel filed a motion to compel discovery, Efe failed to protect his client’s interests, resulting in an award of attorney’s fees and costs against the client. Efe also knowingly declined to respond to demands for information during the disciplinary investigation of this case. Efe’s conduct violated Colo. RPC 1.1 (a lawyer shall provide competent representation to a client); Colo. RPC 1.3 (a lawyer shall act with reasonable diligence and promptness when representing a client); Colo. RPC 1.4(a)(2) (a lawyer shall reasonably consult with the client about the means by which the client’s objectives are to be accomplished); and Colo. RPC 8.1(b) (a lawyer involved in a disciplinary matter shall not knowingly fail to respond to a lawful demand for information from a disciplinary authority). The case file is public per C.R.C.P. -

Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect

STATE STATUTES Current Through March 2019 WHAT’S INSIDE Defining child abuse or Definitions of Child neglect in State law Abuse and Neglect Standards for reporting Child abuse and neglect are defined by Federal Persons responsible for the child and State laws. At the State level, child abuse and neglect may be defined in both civil and criminal Exceptions statutes. This publication presents civil definitions that determine the grounds for intervention by Summaries of State laws State child protective agencies.1 At the Federal level, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment To find statute information for a Act (CAPTA) has defined child abuse and neglect particular State, as "any recent act or failure to act on the part go to of a parent or caregiver that results in death, https://www.childwelfare. serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse, gov/topics/systemwide/ or exploitation, or an act or failure to act that laws-policies/state/. presents an imminent risk of serious harm."2 1 States also may define child abuse and neglect in criminal statutes. These definitions provide the grounds for the arrest and prosecution of the offenders. 2 CAPTA Reauthorization Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-320), 42 U.S.C. § 5101, Note (§ 3). Children’s Bureau/ACYF/ACF/HHS 800.394.3366 | Email: [email protected] | https://www.childwelfare.gov Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect https://www.childwelfare.gov CAPTA defines sexual abuse as follows: and neglect in statute.5 States recognize the different types of abuse in their definitions, including physical abuse, The employment, use, persuasion, inducement, neglect, sexual abuse, and emotional abuse. -

The Eye in Lermontov's a Hero of Our Time

THE EYE IN LERMONTOV’S A HERO OF OUR TIME: PERCEPTION, VISUALITY, AND GENDER RELATIONS by IRYNA IEVGENIIVNA ZAGORUYKO A THESIS Presented to the Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies Program and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2016 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Iryna Ievgeniivna Zagoruyko Title: The Eye in Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time: Perception, Visuality, and Gender Relations This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies Program by: Katya Hokanson Chairperson Jenifer Presto Member Yelaina Kripkov Member and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2016 ! ii © 2016 Iryna Ievgeniivna Zagoruyko ! iii THESIS ABSTRACT Iryna Ievgeniivna Zagoruyko Master of Arts Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies Program June 2016 Title: The Eye in Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time: Perception, Visuality, and Gender Relations This thesis views Lermontov’s novel A Hero of Our Time as centered on images, glances and vision. In his text Lermontov conveys a persistent fascination with visual perception. The attentive reader can read this language of the eye—the eye can be seen as a mirror of the soul, a fetish, a means of control, and a metaphor for knowledge. The texts that form the novel are linked together by a shared preoccupation with the eye. At the same time, these texts explore the theme of visual perception from different angles, and even present us with different attitudes towards vision. -

Collection Adultes Et Jeunesse

bibliothèque Marguerite Audoux collection DVD adultes et jeunesse [mise à jour avril 2015] FILMS Héritage / Hiam Abbass, réal. ABB L'iceberg / Bruno Romy, Fiona Gordon, Dominique Abel, réal., scénario ABE Garage / Lenny Abrahamson, réal ABR Jamais sans toi / Aluizio Abranches, réal. ABR Star Trek / J.J. Abrams, réal. ABR SUPER 8 / Jeffrey Jacob Abrams, réal. ABR Y a-t-il un pilote dans l'avion ? / Jim Abrahams, David Zucker, Jerry Zucker, réal., scénario ABR Omar / Hany Abu-Assad, réal. ABU Paradise now / Hany Abu-Assad, réal., scénario ABU Le dernier des fous / Laurent Achard, réal., scénario ACH Le hérisson / Mona Achache, réal., scénario ACH Everyone else / Maren Ade, réal., scénario ADE Bagdad café / Percy Adlon, réal., scénario ADL Bethléem / Yuval Adler, réal., scénario ADL New York Masala / Nikhil Advani, réal. ADV Argo / Ben Affleck, réal., act. AFF Gone baby gone / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF The town / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF L'âge heureux / Philippe Agostini, réal. AGO Le jardin des délices / Silvano Agosti, réal., scénario AGO La influencia / Pedro Aguilera, réal., scénario AGU Le Ciel de Suely / Karim Aïnouz, réal., scénario AIN Golden eighties / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Hotel Monterey / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Jeanne Dielman 23 quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE La captive / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Les rendez-vous d'Anna / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE News from home / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario, voix AKE De l'autre côté / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Head-on / Fatih Akin, réal, scénario AKI Julie en juillet / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI L'engrenage / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Solino / Fatih Akin, réal. -

October 2019

FILMS RATED/CLASSIFIED From 01 Oct 2019 to 31 Oct 2019 Films and Trailers FILM TITLE DIRECTOR RUN TIME DATE APPROVED DESCRIPTION MEDIA NAME #AnneFrank. Parallel Stories Sabina Fedeli/Anna 2.07 22/10/2019 PG Trailer Migotto 1917 Sam Mendes 2.27 15/10/2019 M Trailer 3 From Hell Rob Zombie 115.49 18/10/2019 R18 Graphic violence, sexual violence, horror & offensive language Film - DCP Abominable Jill Culton, Todd 97 24/10/2019 G Film - DVD Wilderman Ad Astra James Gray 122.55 8/10/2019 M Violence, offensive language & content that may disturb Film - DVD Addams Family, The Greg Tiernan, 86.58 17/10/2019 PG Coarse language Film - DCP Conrad Vernon Aeronauts, The Tom Harper 100.23 8/10/2019 PG Film - DCP All at Sea Robert Young 88.2 10/10/2019 M Film - DCP Am Cu Ce Pride Hannah 19 25/10/2019 PG Offensive language Film - DCP Weissenborn André Rieu: 70 Years Young André Rieu and 1 15/10/2019 G Trailer Michael Wiseman Angel Has Fallen Ric Roman Waugh 121 7/10/2019 R16 Violence & offensive language Film - Harddrive Arctic Justice Aaron Woodley 92 24/10/2019 G Film - DCP Ardab Mutiyaran Manav Shah 139.3 15/10/2019 PG Violence & coarse language Film - DCP At Last Yiwei Liu 1.05 22/10/2019 M Trailer Badlands Terrence Malick 93.37 15/10/2019 M Violence Film - DCP Bala Amar Kaushik 2.47 22/10/2019 M Sexual references Trailer Barefoot Bandits, The: Behind the Voices Ryan Cooper, Alex 4.56 4/10/2019 G Film - DCP Leighton, Tim Evans Barefoot Bandits, The: Glow Your Own Way Comp Ryan Cooper, Alex 0.31 4/10/2019 G Film - DCP Leighton, Tim Evans For Further -

Thomas Hardy: Scripting the Irrational

1 Thomas Hardy: Scripting the Irrational Alan Gordon Smith Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds York St John University School of Humanities, Religion and Philosophy April 2019 2 3 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Alan Gordon Smith to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 4 5 Acknowledgements I am extremely grateful to have been in receipt of the valuable support, creative inspiration and patience of my principal supervisor Rob Edgar throughout my period of study. This has been aided by Jo Waugh’s meticulous attention to detail and vast knowledge of nineteenth-century literature and the early assistance of big Zimmerman fan JT. I am grateful to the NHS for still being on this planet, long may its existence also continue. Much thought and thanks must also go to my late, great Mother, who in the early stages of my life pushed me onwards, initially arguing with the education department of Birmingham City Council when they said that I was not promising enough to do ‘O’ levels. Tim Moore, stepson and good friend must also be thanked for his digital wizardry. Finally, I am immensely grateful to my wife Joyce for her valued help in checking all my final drafts and the manner in which she has encouraged me along the years of my research; standing right beside me as she has always done when I have faced other challenging issues. -

NEW GRID MENTORS ASSUME DUTIES Dr

■ WELCOME TO QUINT LEAVES DAVIDSON FOR STATE COACHES Tin© Davidsomiain TRIP "ALENDA LUX UBI ORTA LIBERTAS" Vol. XIX DAVIDSON COLLEGE, DAVIDSON, N. C, FEBRUARY 10, 1932 No. 17 NEW GRID MENTORS ASSUME DUTIES Dr. C. Darby Fulton Will NEWTON AND McEVER Result of Questionnaire Conduct Mission School ARENAMED COACHES Proves Non-Militaristic Here on February 17-18 of Body Newton Succeeds Coach "Monk" Views Student Prominent Mission Leader to Tell Younger as Head Coach of Students Do Not Sanction Interven- Students of Great Needs in Athletics at Davidson tion of United States Into Sino- ForeignField Japanese Controversy BOTH FROM TENNESSEE HEAD OF MISSION BOARD FAVORABLE TO LEAGUE McEver, for Two Years Ail-American, Coming to Davidson Under Auspices Will Coach Backfield Answers Show That R. O. T. C. Does of Foreign Mission Committee Not Make a Man War-Minded William (Diic) Newton, member of the ()n Tuesday and Wednesday, February 16 ] University of Tennessee athletic staff last fall, As a result" of tile interest in tile Sino-Iap- Eugene McEver, and 1", Dr. C. Darby Fulton, of the Foreign and all American halfback at ancse controversy shown bj the students of Da- same institution, Mission Hoard of the Southern Presbyterian the have since Monday been vidson College, this paper arranged a question- ' directing the spring practice Church, will conduct at Davidson a two-day of the Davidson naire, which was answered l>> the students of Wildcats. mission study institute. the college at the chapel assembly last Thurs- Newton and Monk The main purpose of this study is to present " - McEver succeeded i day morning, The results have been tabulated Younger Tilson, to the student body of this college certain in- .**.T..'s and Tex who next fall go to and in the majority of the cases the expected &.