Of Petr Eben Matthew Markham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Czech Republic

WELCOME TO ČESKÝ T ĚŠÍN/CIESZYN - a one city in two countries Těšín lies at the edge of the Silesian Beskids on the banks of the Olza River, at an elevation of about 300m above sea level. The inhabitants of the original fortifies site belonged to the Lusatian culture. In the years from 1287 to 1653 Tesin was the capitl town of a principality under the rule of the Piast Dynasty (Mieszko I.) A “Religious Order” issued in 1568 confirmed the Evangelical religion of the Augsburg Confession in the town and principality. In 1610, the Counter-Reformation. In 1653 Tesin came under the rule of the Czech kings – the Habsburgs. After a great fire in 1789, the town was rebuilt. An industrial quarter arose on the left bank of the Olza River. In 1826, the Chamber of Tesin was established. At the time the objects on Chateau Hill were rebuilt. The revolutionary events of 1848 aggravated social and national problems. At the end of the First World War the Polish National Council of the Duchy of Tesin (Ducatus Tessinensis). In January 1919 – an attack by the Czech Army. In 1920 – Tesin Silesia as well as the town of Tesin was divided by a state border on the basis of a decision by the Council of Ambassadors in Paris. The western suburbs became an independent town called Český T ěšín. The tenement buildings and public facilities built after the year 1920 following the Art Nouveau are in perfect harmony with older edifices, such as the raiway station or the printing house (1806). -

Aftermath: Accounting for the Holocaust in the Czech Republic

Aftermath: Accounting for the Holocaust in the Czech Republic Krista Hegburg Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERISTY 2013 © 2013 Krista Hegburg All rights reserved Abstract Aftermath: Accounting for the Holocaust in the Czech Republic Krista Hegburg Reparations are often theorized in the vein of juridical accountability: victims of historical injustices call states to account for their suffering; states, in a gesture that marks a restoration of the rule of law, acknowledge and repair these wrongs via financial compensation. But as reparations projects intersect with a consolidation of liberalism that, in the postsocialist Czech Republic, increasingly hinges on a politics of recognition, reparations concomitantly interpellate minority subjects as such, instantiating their precarious inclusion into the body po litic in a way that vexes the both the historical justice and contemporary recognition reparatory projects seek. This dissertation analyzes claims made by Czech Romani Holocaust survivors in reparations programs, the social work apparatus through which they pursued their claims, and the often contradictory demands of the complex legal structures that have governed eligibility for reparations since the immediate aftermath of the war, and argues for an ethnographic examination of the forms of discrepant reciprocity and commensuration that underpin, and often foreclose, attempts to account for the Holocaust in contemporary Europe. Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 18 Recognitions Chapter 2 74 The Veracious Voice: Gypsiology, Historiography, and the Unknown Holocaust Chapter 3 121 Reparations Politics, Czech Style: Law, the Camp, Sovereignty Chapter 4 176 “The Law is Such as It Is” Conclusion 198 The Obligation to Receive Bibliography 202 Appendix I 221 i Acknowledgments I have acquired many debts over the course of researching and writing this dissertation. -

David Eben – Publications &

David Eben – publications & CDs Selected bibliography Die Bedeutung des Arnestus von Pardubitz in der Entwicklung des Prager Offiziums, (Cantus Planus Pécs 1990), Budapest 1992, p. 571-577 Zur Frage von mehreren Melodien bei Offiziums-Antiphonen, Cantus Planus Eger 1993, Budapest 1995, p. 529-537 Organizace liturgického prostoru v bazilice sv. Víta [Organisation of Liturgical Space in Saint Vitus Cathedral in Prague], in: Castrum Pragense 2 (1999), p. 227-240. O mulier / Vade mulier: Lösen eines "Antiphonenknotens", in: Cantus Planus (Visegrád 1998), Budapest 2001, p.119-126 Die Offiziumsantiphonen der Adventszeit, diss. Charles University, Institute of Musicology, Praha 2003 Die Benedictus-Antiphonen von Quatember-Mittwoch und Quatember-Freitag im Prager Ritus, in: Miscelanea Musicologica XXXVII, Praha 2003, p. 63-68 Historical Anthology of Music in the bohemian Lands, ed. Jaromír Černý and others, Praha 2005 (cf. the section of sacred monophony p. 4-30) L´office de saint Eloi dans les manuscrits de la confrérie des orfèvres de Prague, in: De Noyon à Prague, Le culte de Saint Eloi en Bohême médiévale, Praha 2007, p. 115- 156 Der Blick von Oben. Gregorianische Inspiration im Werk von Petr Eben; publikováno ve sborníku z konference: „Musikalische und theologische Etüden zum Verhältnis von Musik und Theologie“, Hg. Wolfgang Müller, Zürich 2012, s. 201-214 Die Evangeliumsantiphonen der Donnerstage in der Fastenzeit, in: Cantus Planus, (Papers read at the 16th meeting, Vienna 2011), Wien 2012, s. 127-134 Eine unbekannte Quelle zum Prager Offizium des hl. Adalbert, in: Hudební věda 2014/1-2, str. 7-20. Recordings with the ensemble Schola Gregoriana Pragensis (cf. www.gregoriana.cz) Toussaint — Requiem - Mass and Office of the feast of All Saints, liturgy for the departed. -

Numbers and Distribution

Numbers and distribution The brown bear used to occur throughout the whole Europe. In the beginning of XIX century its range in Poland had already contracted and was limited to the Carpathians, the Białowieża Forest, the currently non-existent Łódzka Forest and to Kielce region (Jakubiec and Buchalczyk 1987). After World War I bears occurred only in the Eastern Carpathians. In the 1950’ the brown bears was found only in the Tatra Mountains and the Bieszczady Mountains and its population size was estimated at 10-14 individuals only (Buchalczyk 1980). In the following years a slow population increase was observed in the Polish Carpathians. Currently the brown bear’s range in Poland is limited to the Carpathians and stretches along the Polish-Slovak border. Occasional observations are made in the Sudetes where one migrating individual was recorded in the 1990’ (Jakubiec 1995). The total range of the brown bear in Poland is estimated at 5400-6500 km2. The area available for bears based on the predicative model for the habitat is much larger and may reach 68 700km2 (within which approx. 29000 km2 offers suitable breeding sites) (Fernández et al. 2012). Currently experts estimate the numbers of bears in Poland at merely 95 individuals. There are 3 main area of bear occurrence: 1. the Bieszczady Mountains, the Low Beskids, The Sącz Beskids and the Gorce Mountains, 2. the Tatra Mountains, 3. the Silesian Beskids and the Żywiec Beskids. It must be noted, however, that bears only breed in the Bieszczady Mountains, the Tatra Mountains and in the Żywiec Beskids. Poland is the north limit range of the Carpathian population (Swenson et al. -

Petr Eben's Oratorio Apologia Sokratus

© 2010 Nelly Matova PETR EBEN’S ORATORIO APOLOGIA SOKRATUS (1967) AND BALLET CURSES AND BLESSINGS (1983): AN INTERPRETATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SYMBOLISM BEHIND THE TEXT SETTINGS AND MUSICAL STYLE BY NELLY MATOVA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Choral Music in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Donna Buchanan, Chair Professor Sever Tipei Assistant Professor David Cooper Assistant Professor Ricardo Herrera ABSTRACT The Czech composer Petr Eben (1927-2007) has written music in all genres except symphony, but he is highly recognized for his organ and choral compositions, which are his preferred genres. His vocal works include choral songs and vocal- instrumental works at a wide range of difficulty levels, from simple pedagogical songs to very advanced and technically challenging compositions. This study examines two of Eben‘s vocal-instrumental compositions. The oratorio Apologia Sokratus (1967) is a three-movement work; its libretto is based on Plato‘s Apology of Socrates. The ballet Curses and Blessings (1983) has a libretto compiled from numerous texts from the thirteenth to the twentieth centuries. The formal design of the ballet is unusual—a three-movement composition where the first is choral, the second is orchestral, and the third combines the previous two played simultaneously. Eben assembled the libretti for both compositions and they both address the contrasting sides of the human soul, evil and good, and the everlasting fight between them. This unity and contrast is the philosophical foundation for both compositions. -

JULIETTE at the BARBICAN, LONDON the PRAGUE SPRING FESTIVAL 2009 Martinůmay—Augustrevue 2009 VOL.IX NO

THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ FOUNDATION THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ INSTITUTE THE INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE JULIETTE AT THE BARBICAN, LONDON THE PRAGUE SPRING FESTIVAL 2009 martinůMAY—AUGUSTrevue 2009 VOL.IX NO. 2 CONFERENCES / EXHIBITIONS LIST OF MARTINŮ’S WORKS / PART VI NEWS / EVENTS ∑ exhibition THE BOHUSLAV contents MARTINŮ CENTER IN POLIČKA 3 Martinů Revisited Highlights —Visit the newly opened 4 Incircle News permanent exhibition GREGORY TERIAN dedicated to the composer’s life and work (authored by 5 International Martinů Circle Prof. Jaroslav Mihule) 6 martinů revisited —We offer visitors a tour of the reconstructed classroom —Exhibition – The Martinů Phenomenon attended by Martinů as a schoolboy and a musical hall —Journée Martinů in Paris where one can listen to recordings or attend film screenings and specialised lectures. 7 Hommage à Martinů in Budapest Ballet Productions in Brno www.cbmpolicka.cz [email protected] 8 Juliette at the Barbican Centre in London PATRICK LAMBERT 9 In a Forest of Giant Poppy-Heads BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ opera LENKA ŠALDOVÁ THE MARRIAGE H.341 11 special series —List of Martinů’s Works VI 1953, comic chamber opera from the play by Nikolai Gogol 12 news / conferences / original creation by Pamela Howard autographs Jakub Klecker (Conductor) 14 review NATIONAL THEATRE BRNO / REDUTA THEATRE —Martinů Revisits Prague Spring 4 October 2009 > premiere GRAHAM MELVILLE-MASON 5 & 7 October 2009 16 interview www.ndbrno.cz —Alan Buribayev – A Rising Conducting Star MARTINA FIALKOVÁ 18 events 19 news —New Publications, CD ∑ highlights IN 2009 THE CULTURAL WORLD commemorates the 50th anniversary of Bohuslav Martinů’s death (28 August 1959). In anticipation of this anniversary year, many organisers in the Czech Republic and abroad have prepared music productions at which the composer’s works will be performed. -

Choral Secular Music Through the Ages

Choral Secular Music through the ages The Naxos catalogue for secular choral music is such a rich collection of treasures, it almost defi es description. All periods are represented, from Adam de la Halle’s medieval romp Le Jeu de Robin et Marion, the earliest known opera, to the extraordinary fusion of ethnic and avant-garde styles in Leonardo Balada’s María Sabina. Core repertoire includes cantatas by J.S. Bach, Beethoven’s glorious Symphony No. 9, and a “must have” (Classic FM) version of Carl Orff’s famous Carmina Burana conducted by Marin Alsop. You can explore national styles and traditions from the British clarity of Elgar, Finzi, Britten and Tippett, to the stateside eloquence of Eric Whitacre’s “superb” (Gramophone) choral program, William Bolcom’s ‘Best Classical Album’ Grammy award winning William Blake songs, and Samuel Barber’s much loved choral music. Staggering emotional range extends from the anguish and passion in Gesualdo’s and Monteverdi’s Madrigals, through the stern intensity of Shostakovich’s Execution of Stepan Razin to the riot of color and wit which is Maurice Saylor’s The Hunting of the Snark. Grand narratives such as Handel’s Hercules and Martinů’s Epic of Gilgamesh can be found alongside tender miniatures by Schubert and Webern. The Naxos promise of uncompromising standards of quality at affordable prices is upheld both in performances and recordings. You will fi nd leading soloists and choirs conducted by familiar names such as Antoni Wit, Gerard Schwarz, Leonard Slatkin and Robert Craft. There is also a vast resource of collections available, from Elizabethan, Renaissance and Flemish songs and French chansons to American choral works, music for children, Red Army Choruses, singing nuns, and Broadway favorites – indeed, something for everyone. -

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints/Mormon Children’S Music: Its History, Transmission, and Place in Children’S Cognitive Development

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS/MORMON CHILDREN’S MUSIC: ITS HISTORY, TRANSMISSION, AND PLACE IN CHILDREN’S COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT Colleen Jillian Karnas-Haines, Doctor of Philosophy, 2005. Dissertation Directed by: Professor Robert C. Provine Division of Musicology and Ethnomusicology School of Music The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a children’s auxiliary program for ages three to eleven that meets weekly before or after their Sunday worship service. This auxiliary, called Primary, devotes much of its time to singing. Music is not a childish diversion, but an essential activity in the children’s religious education. This study examines the history of the songbooks published for Primary use, revealing the many religious and cultural factors that influence the compilations. The study then looks at the modern methods of transmission as the author observes the music education aspects of Primary. Lastly, the study investigates the children’s use of and beliefs about Primary music through the lens of cognitive development. The study reveals that Primary music is an ever-evolving reflection of the theology, cultural trends, and practical needs of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Unaware of such implications, the children use Primary music to express their religious musicality at cognitive developmentally appropriate levels. THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS/MORMON CHILDREN’S MUSIC: ITS HISTORY, TRANSMISSION, AND PLACE IN CHILDREN’S COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT By Colleen Jillian Karnas-Haines Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2005 Advisory Committee: Professor Robert C. -

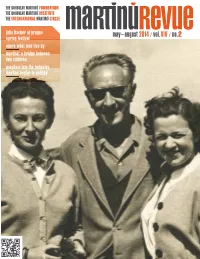

May–August 2014/ Vol.XIV / No.2

THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ FOUNDATION THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ INSTITUTE THE INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE MR julia fischer at prague may–august 2014 / vol.XIV / no.2 spring festival opera what men live by martinů: a bridge between two cultures peephole into the bohuslav martinů center in polička BOHUSLAVMARTINŮ INTHEYEAR OFCZECH MUSIC & BOHUSLAVMARTINŮ DAYS contents 2014 3 PROLOGUE 4 14+15+16 SEPTEMBER 2014 9.00 pm . Lesser Town of Prague Cemetery 5 Eva Blažíčková – choreographer MARTINŮ . The Bouquet of Flowers, H 260 6 7 OCTOBER 2014 . 8.30 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ’S SOLDIER Concert in the occasion of 100th anniversary of Josef Páleníček’s birth Smetana Trio, Wenzel Grund – clarinet AND DANCER MARTINŮ . Piano Trio No 2, H 327 OLGA JANÁČKOVÁ (+ PÁLENÍČEK, JANÁČEK) THE SOLDIER AND THE DANCER IN PLZEŇ 2 NOVEMBER 2014 . 7.00 pm . National Theatre, Prague EVA VELICKÁ Ballet ensemble of the National Moravian-Silesian Theatre, Nataša Novotná – choreographer 8 MARTINŮ . The Strangler, H 314 (+ SMETANA, JANÁČEK) GEOFF PIPER MARTINA FIALKOVÁ 2 DECEMBER 2014 . 5.00 pm . Hall of Prague Conservatory Concert Marking the 40th Anniversary of the Dvořák Society for Czech and Slovak Music – programme see page 3 10 JULIA FISCHER AT PRAGUE SPRING BOHUSLAV . MARTINU DAYS FESTIVAL FRANK KUZNIK 30 NOVEMBER 2014 . 7.00 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague TWO STARS ENCHANT THE RUDOLFINUM Concert of the winners of Bohuslav Martinů Competition PRAVOSLAV KOHOUT in the Category Piano Trio and String Quartet 2 DECEMBER 2014 . 7.30 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague 12 Kühn Children's Choir, choirmasters: Jiří Chvála, Petr Louženský WHAT MEN LIVE BY Panocha Quartet members (Jiří Panocha, Pavel Zejfart – violin, GREGORY TERIAN Miroslav Sehnoutka – viola), Jan Kalfus – organ, Petr Kostka – recitation, Ivan Kusnjer – baritone, Daniel Wiesner – piano MARTINŮ . -

Euroregion Silesia

EUROREGION SILESIA Silesian Province / Moravian-Silesian Region Woiwodschaft Schlesien / Mährisch-Schlesische Region Cultural heritage Active leisure Kulturerbe Aktive Erholung Piast Castle in Racibórz (with chapel) The „Three Hills” Family Leisure Park in Wodzisław Śląski 1 Piastenschloss in Ratibor (mit Kapelle) 16 Familienunterhaltungspark „Drei Hügel“ in Loslau Wodzisław Śląski The Odra Kayak Trail - kayaking trips 2 Loslau (kayak marinas in Racibórz, Zabełków and Chałupki) 17 Kajak-Oderweg - Paddeltouren Głubczyce with its City Hall, defensive walls and towers (Anlegestellen in Ratibor, Zabelkau und Annaberg) 3 Leobschütz samt dem Städtischen Rathaus sowie den The multi-purpose sports centre Schutzmauern und Wehrtürmen 18 with artificial ice rink in Pszów Multifunktionales Sportobjekt mit Kunsteisbahn in Pschow 4 Ruins of the Castle in Tworków Ruinen des Schlosses in Tworkau „Sunny Island” in Marklowice 19 „Sonneninsel“ w Markowitz Pilgrimage Church of the Holy Cross in Pietrowice Wielkie 5 „H2Ostróg” Waterpark in Racibórz Wallfahrtskirche zum Heiligen Kreuz 20 in Groß Peterwitz Aquapark „H2Ostróg” in Ratibor The wooden church of Saint Joseph and Saint Barbara The „Nautica” Tourism, Sports and Recreation Community 6 in Baborów Centre in Gorzyce Holzkirche der Heiligen Josef und Barbara in Bauerwitz 21 Gemeindezentrum für Tourismus, Sport und Erholung „Nautica“ in Gorschütz The Historic Narrow-Gauge Railway Station in Rudy 7 Denkmalgeschützte Schmalspurbahn in Groß Rauden The city beach in Racibórz 22 Stadtstrand in Ratibor Hradec -

Emily Dickinson Poetry by Osvaldo Golijov, Ricky Ian Gordon, Lori Laitman, Jake Heggie, Libby Larsen, André Previn, and Juliana Hall

SELECTED MODERN SETTINGS OF EMILY DICKINSON POETRY BY OSVALDO GOLIJOV, RICKY IAN GORDON, LORI LAITMAN, JAKE HEGGIE, LIBBY LARSEN, ANDRÉ PREVIN, AND JULIANA HALL by Laurie Staring Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2020 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Patricia Havranek, Chair and Research Director ______________________________________ Brian Horne ______________________________________ Marietta Simpson ______________________________________ Ayana Smith December 4, 2019 ii To my research committee, for their help and patience, I offer my deepest gratitude. To my voice teacher and research director, Patricia Havranek, you are a model of grace and intelligence, and I thank you for your mentorship. To my parents, Roy and Rita Staring, thank you for your unfailing support and love. And to my husband, Alex, thank you for every day I have with you. iii Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................. iv List of Musical Examples ................................................................................................................. v Chapter 1 : Introduction ................................................................................................................... -

December 2019 Nase Rodina

Naše rodina “Our Family” Quarterly of the Czechoslovak Genealogical Society International March 2020 Volume 32 Number 1 some words about my genealogy en- A Path of Coincidences Leads deavors and the work of the CGSI. The trip in 2000 was my last to the Genealogy Jackpot one until May of 2018 when I took a By Paul Makousky, Publications Chair 3-week trip with my daughter Katie covering both Czechia and Slova- kia. Our first day of the trip was My most interesting genealogy find Genealogical Society International scheduled for Velké Meziříčí to visit began due to a 28-year old con- (CGSI) that he had been introduced 94-year-old Vladimír Makovský, nection I had made with Vladimír to by me. who I always thought was related Makovský of Velké Meziříčí, a I first met Vladimír in person on city of some 10,000 people located a trip to the Česká a Slovenská Fed- Continued on page 3 on the main highway from Prague erativní Republika (i.e. Czech and towards Brno. This find was not Slovak Federated Republic, (ČSFR) Theme of This Issue: associated with my family, but read in 1991. On subsequent trips in Genealogists’ Most Interesting on. Vladimír founded the Velké 1993, 1995, 1997, and 2000 I also Findings Meziříčí Genealogy Club in 1992 at visited with him. On many of those 1 – A Path of Coincidences Leads to the Jupiter Klub, after being inspired trips I traveled to Velké Meziříčí and the Genealogy Jackpot by the work of the Czechoslovak was asked on two occasions to say 2 – President’s Message 7 – Intriguing Items from Slovak Church Records 10 –