The Building of a Wooden Ship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armed Sloop Welcome Crew Training Manual

HMAS WELCOME ARMED SLOOP WELCOME CREW TRAINING MANUAL Discovery Center ~ Great Lakes 13268 S. West Bayshore Drive Traverse City, Michigan 49684 231-946-2647 [email protected] (c) Maritime Heritage Alliance 2011 1 1770's WELCOME History of the 1770's British Armed Sloop, WELCOME About mid 1700’s John Askin came over from Ireland to fight for the British in the American Colonies during the French and Indian War (in Europe known as the Seven Years War). When the war ended he had an opportunity to go back to Ireland, but stayed here and set up his own business. He and a partner formed a trading company that eventually went bankrupt and Askin spent over 10 years paying off his debt. He then formed a new company called the Southwest Fur Trading Company; his territory was from Montreal on the east to Minnesota on the west including all of the Northern Great Lakes. He had three boats built: Welcome, Felicity and Archange. Welcome is believed to be the first vessel he had constructed for his fur trade. Felicity and Archange were named after his daughter and wife. The origin of Welcome’s name is not known. He had two wives, a European wife in Detroit and an Indian wife up in the Straits. His wife in Detroit knew about the Indian wife and had accepted this and in turn she also made sure that all the children of his Indian wife received schooling. Felicity married a man by the name of Brush (Brush Street in Detroit is named after him). -

A Very Short Guide to Knotting Terminology Used on These Pages

KNOTS A very short guide to knotting terminology used on these pages. This is not an exhaustive list of knotting terms; it just contains some of the more unfamiliar words that we have used. If you wish to research the subject further, any good book on knots should have a knotting glossary. • Knot. Strictly speaking, a knot is tied in the end of a line as a stopper, such as the Thumb knot or Figure of eight knot. • Stopper knots are used to stop the end of a rope fraying, or to stop it running through a small hole or constriction. • Bend. A bend is used to tie two ropes together, as in the Sheet bend. Technically, even the Reef knot is a bend. • Hitch. A hitch is used to tie a rope to a spar, ring or post, such as the Clove hitch. Hitches can also be used to tie one rope onto another rope, as in the Rolling hitch. • Running End - the end of the rope that is being used to tie the knot. • Standing End - the static end of the rope. • Splice – A splice is used to fasten two ends of a rope together when a knot would be impracticable, as, for instance, when the rope must pass through a pulley. • Bight can have two meanings: -- The main part of the rope from the running end to the standing end -- Where the rope is bent back to form a loop. • Jam - when the knot tightens under tension and you cannot get it undone! Blackwall Hitch This is a simple half hitch over a hook. -

Sound Explorations Educator Packet 2017.Pub

Sound Explorations Educator Packet (360) 379-0438 PO Box 1390 Port Townsend, WA 98368 Email: [email protected] Fax: (360) 379-0439 www.soundexp.org Dear Educator, Thank you for choosing Sound Experience for a fun and exciting, hands- on learning experience aboard Adventuress for your group! This is an active learning and working voyage designed to enhance the curriculum in your classroom and build community through experiential programming aboard the schooner Adventuress. This pre-trip packet contains important information about your upcoming voyage. Please read it over thoroughly and utilize the checklist to ensure all required documents are turned in prior to the trip. Included is an overview of curriculum for the Sound Explorations program, history and information about the ship, required paperwork, and reference and resource lists you may use with your class before or after the trip to enhance the learning experience. You may visit http:// www.soundexp.org/index.php?page=teacherinfo for a few suggested activities for before and after your voyage. I will contact you approximately three weeks before your trip to cover any last minute details and gather any additional information about your group and program interests relevant to this trip. We do our best to tailor the experience within our ability. Please do not hesitate to call if you have any questions or concerns. Sincerely, Amy Kovacs Education Director Sound Experience P.O. Box 1390 Port Townsend, WA 98368 (360) 379-0438, ext. 2 (Phone) (360) 379-0439 (FAX) E-mail: [email protected] Website: www. soundexp. org Welcome! Sound Experience welcomes you to the historic schooner Adventuress for a voyage of exploration on Puget Sound. -

Addendum to CORNISH-WINDSOR BRIDGE HAER No. NH-8 (Page 1)

Addendum to CORNISH-WINDSOR BRIDGE HAER No. NH-8 (Page 1) Introduction The Cornish-Windsor Bridge, the longest surviving covered bridge in the United States and the longest two-span covered bridge in the world, is a rare example of the notched squared timber Town lattice truss design.1 Built in 1866, it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and the American Society of Civil Engineers designated it as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1970. One of the objectives of this study was to review and summarize the technical bibliography published about Cornish-Windsor Bridge. Since the bridge has an extraordinary span, its history includes a series of reinforcement, rehabilitation, and preservation issues that are worthy of study. The notched squared timber Town lattice truss is important as it represents a specific solution and modification to a known design to achieve a high load-bearing capacity and a high degree of stiffness, or rigidity, in a long structure. Notched squared timber Town lattice trusses, patented by Ithiel Town in 1839, represent a compromise-based solution by including fitted joints in the lattice. The most frequently cited advantage of the Town lattice trusses was that they did not need specialized carpentry work. Replacing overlapped planks and treenail joints with large-section lumber and notched joints meant that this criterion was not totally respected, though scarf (notched) joints–even if the members met at angles other than 90 degrees–were one of the simplest carpentry joints to make. The early development of wooden truss bridges and a general description of the major types, including the Town lattice truss, has been presented in detail in the history report for this bridge, and in materials listed in the bibliography, so they will not be repeated herein.2 The principal objectives of this study were: • to summarize technical information on notched squared timber Town lattice trusses generally and on Cornish-Windsor Bridge in particular. -

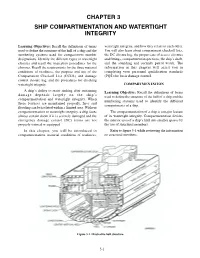

Chapter 3 Ship Compartmentation and Watertight Integrity

CHAPTER 3 SHIP COMPARTMENTATION AND WATERTIGHT INTEGRITY Learning Objectives: Recall the definitions of terms watertight integrity, and how they relate to each other. used to define the structure of the hull of a ship and the You will also learn about compartment checkoff lists, numbering systems used for compartment number the DC closure log, the proper care of access closures designations. Identify the different types of watertight and fittings, compartment inspections, the ship’s draft, closures and recall the inspection procedures for the and the sounding and security patrol watch. The closures. Recall the requirements for the three material information in this chapter will assist you in conditions of readiness, the purpose and use of the completing your personnel qualification standards Compartment Checkoff List (CCOL) and damage (PQS) for basic damage control. control closure log, and the procedures for checking watertight integrity. COMPARTMENTATION A ship’s ability to resist sinking after sustaining Learning Objective: Recall the definitions of terms damage depends largely on the ship’s used to define the structure of the hull of a ship and the compartmentation and watertight integrity. When numbering systems used to identify the different these features are maintained properly, fires and compartments of a ship. flooding can be isolated within a limited area. Without compartmentation or watertight integrity, a ship faces The compartmentation of a ship is a major feature almost certain doom if it is severely damaged and the of its watertight integrity. Compartmentation divides emergency damage control (DC) teams are not the interior area of a ship’s hull into smaller spaces by properly trained or equipped. -

Back Issues of BCAS Publications Published on This Site Are Intended for Non-Commercial Use Only. Photographs and Other Graphics

Back issues of BCAS publications published on this site are intended for non-commercial use only. Photographs and other graphics that appear in articles are expressly not to be reproduced other than for personal use. All rights reserved. CONTENTS Vol. 23, No. 4: October–December 1991 • Larry Lohmann - Peasants, Plantations, and Pulp: The Politics of Eucalyptus in Thailand • Michael Goldman - Cultivating Hot Peppers and Water Crises in India’s Desert: Towards a Theory of Understanding Ecological Crisis • John Price - The 1960 Miike Coal Mine Dispute: Turning Point for Adversarial Unionism in Japan? • Ronald R. Janssen - Words About Pictures / A Review Essay • Zhu Qingpu -Imperialism and Incorporation - The Case of Chinese Silk / A Review Essay • John Lie - Rethinking the Miracle: Economic Growth and Political Struggles in South Korea / A Review BCAS/Critical Asian Studies www.bcasnet.org CCAS Statement of Purpose Critical Asian Studies continues to be inspired by the statement of purpose formulated in 1969 by its parent organization, the Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars (CCAS). CCAS ceased to exist as an organization in 1979, but the BCAS board decided in 1993 that the CCAS Statement of Purpose should be published in our journal at least once a year. We first came together in opposition to the brutal aggression of the United States in Vietnam and to the complicity or silence of our profession with regard to that policy. Those in the field of Asian studies bear responsibility for the consequences of their research and the political posture of their profession. We are concerned about the present unwillingness of specialists to speak out against the implications of an Asian policy committed to en- suring American domination of much of Asia. -

Utilization of Black Locust

UTILI"ATION OF BLAC"LOCUST B y "O H N B . ( Dru m Associ a te W ood Tech n o l o i st For est P r od u cts L a bor a tor Br a n ch o Res g , y, f ea r ch , For est S er vi ce CO NT ENT S o ) o t 9 c O Int r oduct io n H Utiliz ati on Th e t r ee M Insul at or pins Range M W agon hubs H a b it s an d gr owt h M T r eenails Repr oduction W Fence post s Annual cu t an d pr esent supply Q M ine t i mber s ‘ Cut ting an d mar keting O Poles Th e wood Q M inor uses Appear ance Q Summar y St r uct ur e G A ppendix Pr o per ties N Specifi cat i ons for insul at or pins Specifi cations for t r eenails I N T R O D UC T I O N Ro bi 'n i a seu d oacaci a " The wood of black locust , p , is used chie y for insulator pins , wagon hubs , treenails , fence posts , and mine F r . o timbers these uses it is admirable because of its hardness , A i s strength , and durability . valuable characteristic of the tree its rapid growth on many types of soils during the first 20 to 30 years of its life . This rapid growth and the extensive network of roots developed by black locust make it well suited fo r planting t o check erosion . -

Cape Cod Catboat

Cape Cod Catboat Instructions: Follow these instructions carefully and step by step. The rigging lines of the boat could tangle easily so do not undo the lines until instructed. 1. Unwrap the hull and stand. Place the hull into the stand with the hull facing forward to your right. Keep the starboard side of the boat facing you in order to follow the instructions and to compare with the diagrams. 2. Study brass eye “A” and the cleats on the boat. There are 7 cleats on this model but we will only be using 3-7. They each have a fixed position that corresponds to different rigging lines and sail sheets of the boat. See diagram (1). 3. Unwrap the packing of the mast; find brass eyes G1, G2, G3, G4, & G5 on the mast. The brass eyes must face towards the stern of the boat. Insert the mast into the mast step on the deck. 4. Unpack the sail. You may want to press the sail with an iron to get out any wrinkles. Find the headstay line on the front top portion of the mast. Attach the line to eye A on the bow. See diagram (1). 5. Put the gaff jaw at the end of gaff pole to brass eye M on the mast. Then find a pin at the end of the boom, insert the pin to a brass hole about 1 inch up the mast from the deck. Find a block with hook on the topping lift line. Attach the hook of the line to eye G1, then lead the line down the mast and through an eye at the bottom of the mast, starboard side, then fix the end of the line to cleat 4 on the cockpit bulkhead. -

Coast Guard Cutter Seamanship Manual

U.S. Department of Homeland Security United States Coast Guard COAST GUARD CUTTER SEAMANSHIP MANUAL COMDTINST M3120.9 November 2020 Commandant US Coast Guard Stop 7324 United States Coast Guard 2703 Martin Luther King Jr. Ave SE Washington, DC 20593-7324 Staff Symbol: (CG-751) Phone: (202) 372-2330 COMDTINST M3120.9 04 NOV 2020 COMMANDANT INSTRUCTION M3120.9 Subj: COAST GUARD CUTTER SEAMANSHIP MANUAL Ref: (a) Risk Management (RM), COMDTINST 3500.3 (series) (b) Rescue and Survival Systems Manual, COMDTINST M10470.10 (series) (c) Cutter Organization Manual, COMDTINST M5400.16 (series) (d) Naval Engineering Manual, COMDTINST M9000.6 (series) (e) Naval Ships' Technical Manual (NSTM), Wire and Fiber Rope and Rigging, Chapter 613 (f) Naval Ships’ Technical Manual (NSTM), Mooring and Towing, Chapter 582 (g) Cutter Anchoring Operations Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTP), CGTTP 3-91.19 (h) Cutter Training and Qualification Manual, COMDTINST M3502.4 (series) (i) Shipboard Side Launch and Recovery Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTP), CGTTP 3-91.25 (series) (j) Shipboard Launch and Recovery: WMSL 418’ Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTP), CGTTP 3-91.7 (series) (k) Naval Ships’ Technical Manual (NSTM), Boats and Small Craft, Chapter 583 (l) Naval Ship’s Technical Manual (NSTM), Cranes, Chapter 589 (m) Cutter Astern Fueling at Sea (AFAS) Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTP), CGTTP 3-91.20 (n) Helicopter Hoisting for Non-Flight Deck Vessels, Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTP), CGTTP 3-91.26 (o) Flight Manual USCG Series -

WIND MEASURING SYSTEMS Using Xdi-N Indicators

APPLICATION NOTES WIND MEASURING SYSTEMS using XDi-N indicators Document no.: 4189350080C Wind Measuring Systems Application notes, using XDi-N indicators Table of contents GENERAL INFORMATION .......................................................................................................... 4 WARNINGS, LEGAL INFORMATION AND SAFETY ............................................................................... 4 LEGAL INFORMATION AND DISCLAIMER ........................................................................................... 4 DISCLAIMER ................................................................................................................................. 4 SAFETY ISSUES ............................................................................................................................ 4 ELECTROSTATIC DISCHARGE AWARENESS ..................................................................................... 4 FACTORY SETTINGS ..................................................................................................................... 4 ABOUT THE APPLICATION NOTES........................................................................................... 5 GENERAL PURPOSE ...................................................................................................................... 5 INTENDED USERS ......................................................................................................................... 5 CONTENTS/OVERALL STRUCTURE ................................................................................................. -

U.S. Navy Ships-Of-The-Line

U.S. Navy – Ships-of-the-line A Frigate vs A Ship-of-the-Line: What’s the difference? FRIGATE: A vessel of war which is: 1) “ship” rigged, i.e. – with at least three masts (fore, main, & mizzen) & each mast carries the horizontal yards from which the principle sails are set; 2) this “ship-rigged vessel of war” is a FRIGATE because it has one covered, principle gun deck – USS Constitution is therefore a FRIGATE by class (illus. left) SHIP-OF-THE-LINE: A vessel of war which is: 1) “ship” rigged (see above); 2) this “ship-rigged vessel of war” is a SHIP-OF-THE-LINE because it has two or more covered gun decks – HMS Victory is therefore a SHIP-OF-THE-LINE by class (illus. right) HMS Victory (1765); 100+ guns; 820 officers Constitution preparing to battle Guerriere, & crew; oldest commissioned warship in the M.F. Corne, 1812 – PEM Coll. world, permanently dry docked in England Pg. 1 NMM Coll. An Act, 2 January 1813 – for the construction of the U.S. Navy’s first Ships-of-the-line USS Independence was the first ship-of-the-line launched for the USN from the Boston (Charlestown) Navy Yard on 22 June 1814: While rated for 74-guns, Independence was armed with 87 guns when she was launched. USS Washington was launched at the Portsmouth Navy Yard, 1 October 1814 USS Pennsylvania – largest sailing warship built for the USN USS Pennsylvania – rated for 136 guns on three covered gun decks + guns on her upper (spar) deck – the largest sailing warship ever built. -

Chapter 12 Review

FIGURE 12.1: “The Swan Range,” photograph by Donnie Sexton, no date 1883 1910 1869 1883 First transcontinental Northern Pacifi c Railroad completes Great Fire 1876 Copper boom transcontinental route railroad completed begins in Butte Battle of the 1889 1861–65 Little Bighorn 1908 Civil War Montana becomes a state Model T invented 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1862 1882 1862 Montana gold Montana Improvement Anton Holter opens fi rst 1875 rush begins Salish stop setting Company formed 1891 1905 commercial sawmill in Forest Reserve Act U.S. Forest Montana Territory fi res after confrontation 230 with law enforcement Service created READ TO FIND OUT: n How American Indians traditionally used fire n Who controlled Montana’s timber industry n What it was like to work as a lumberjack n When and why fire policy changed The Big Picture For thousands of years people have used forests to fill many different needs. Montana’s forestlands support our economy, our communities, our homes, and our lives. Forests have always been important to life in Montana. Have you ever sat under a tall pine tree, looked up at its branches sweeping the sky, and wondered what was happen- ing when that tree first sprouted? Some trees in Montana are 300 or 400 years old—the oldest living creatures in the state. They rooted before horses came to the Plains. Think of all that has happened within their life spans. Trees and forests are a big part of life in Montana. They support our economy, employ our people, build our homes, protect our rivers, provide habitat for wildlife, influence poli- tics, and give us beautiful places to play and be quiet.