Grounds for War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cancel Culture: Posthuman Hauntologies in Digital Rhetoric and the Latent Values of Virtual Community Networks

CANCEL CULTURE: POSTHUMAN HAUNTOLOGIES IN DIGITAL RHETORIC AND THE LATENT VALUES OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITY NETWORKS By Austin Michael Hooks Heather Palmer Rik Hunter Associate Professor of English Associate Professor of English (Chair) (Committee Member) Matthew Guy Associate Professor of English (Committee Member) CANCEL CULTURE: POSTHUMAN HAUNTOLOGIES IN DIGITAL RHETORIC AND THE LATENT VALUES OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITY NETWORKS By Austin Michael Hooks A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of English The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee August 2020 ii Copyright © 2020 By Austin Michael Hooks All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT This study explores how modern epideictic practices enact latent community values by analyzing modern call-out culture, a form of public shaming that aims to hold individuals responsible for perceived politically incorrect behavior via social media, and cancel culture, a boycott of such behavior and a variant of call-out culture. As a result, this thesis is mainly concerned with the capacity of words, iterated within the archive of social media, to haunt us— both culturally and informatically. Through hauntology, this study hopes to understand a modern discourse community that is bound by an epideictic framework that specializes in the deconstruction of the individual’s ethos via the constant demonization and incitement of past, current, and possible social media expressions. The primary goal of this study is to understand how these practices function within a capitalistic framework and mirror the performativity of capital by reducing affective human interactions to that of a transaction. -

Gretchen Bakke Curriculum Vitae

Gretchen Bakke curriculum vitae CONTACT: Integrative Research Institute on Transformations of Human-Environment Systems (IRI THESys) Humboldt- Universität zu Berlin, Unter den Linden 6, 10099 Berlin GERMANY [email protected]; www.bakkeconsolidated.org EDUCATION: Doctor of Philosophy, University of Chicago – Cultural Anthropology 2007 Master of Arts, Indiana University – Russian and East European Studies 1997 Bachelor of Arts, The Evergreen State College – Sovietology; Photography 1993 CURRENT POSITIONS: 2018-2020 Guest Professor, Chair of Social Anthropology, Institute for European Ethnology and Institute on Transformations of Human-Environment Systems, Humboldt University, Berlin 2018-2021 Anthropocene Working Group, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin 2019- Section Editor, Systems and Futures, Public Books, New York, USA RESEARCH AND HONORARY AFFILIATIONS: 2020-2021 Honorary Research Fellow, School of Social Science, University of Aberdeen, Scotland UK 2019-2022 Status Professor, Anthropology, University of Toronto, Toronto Canada PREVIOUS POSITIONS: 2012-2020 Assistant Professor, Anthropology, McGill University, Montréal QC (on-leave 2018-2020) 2009-2010 Research Fellow, Science in Society Program, Wesleyan University, Middletown CT 2008-2009 Postdoctoral Fellow, Center for the Humanities, Wesleyan University, Middletown CT 2005-2007 Editorial Assistant/Staff Photographer, American Anthropological Assoc., Arlington VA 1999-2000 Editorial Assistant, Public Culture, Chicago IL 1998-1999 Research Assistant /Translator -

The Dark Triad Traits Predict Authoritarian Political Correctness and Alt-Right Attitudes

Heliyon 6 (2020) e04453 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Heliyon journal homepage: www.cell.com/heliyon Research article The Dark Triad traits predict authoritarian political correctness and alt-right attitudes Jordan Moss a,*, Peter J. O'Connor b a School of Psychology and Counselling, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia b School of Management, QUT Business School, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: It is well established that mainstream personality traits are associated with moderate, traditional political atti- Psychology tudes. However, very little is known regarding trait predictors of extreme political attitudes. In the current study Applied psychology (N ¼ 511 U.S. residents), we examined the relationships between the Dark Triad traits, Entitlement and three Individual differences extreme political attitudes that are highly covered in mainstream media: White Identitarianism (‘Alt-Right’), Personality assessment Political Correctness-Authoritarianism, and Political Correctness-Liberalism. We found that Dark Triad traits and Political behavior Political correctness Entitlement had incremental validity in the prediction of these 3 attitudes over demographic factors. The Dark Dark triad Triad traits and Entitlement explained a substantial portion of variance in White Identitarianism and Political Alt right Correctness-Authoritarianism, and only a small portion of variance in Political Correctness-Liberalism. Across all Extremism attitudes, Psychopathy -

Von Influencer*Innen Lernen Youtube & Co

STUDIEN MARIUS LIEDTKE UND DANIEL MARWECKI VON INFLUENCER*INNEN LERNEN YOUTUBE & CO. ALS SPIELFELDER LINKER POLITIK UND BILDUNGSARBEIT MARIUS LIEDTKE UND DANIEL MARWECKI VON INFLUENCER*INNEN LERNEN YOUTUBE & CO. ALS SPIELFELDER LINKER POLITIK UND BILDUNGSARBEIT Studie im Auftrag der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung MARIUS LIEDTKE arbeitet in Berlin als freier Medienschaffender und Redakteur. Außerdem beendet er aktuell sein Master-Studium der Soziokulturellen Studien an der Europa-Universität Viadrina in Frankfurt (Oder). In seiner Abschlussarbeit setzt er die Forschung zu linken politischen Influencer*innen auf YouTube fort. DANIEL MARWECKI ist Dozent für Internationale Politik und Geschichte an der University of Leeds. Dazu nimmt er Lehraufträge an der SOAS University of London wahr, wo er auch 2018 promovierte. Er mag keinen akademi- schen Jargon, sondern progressives Wissen für alle. IMPRESSUM STUDIEN 7/2019, 1. Auflage wird herausgegeben von der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung V. i. S. d. P.: Henning Heine Franz-Mehring-Platz 1 · 10243 Berlin · www.rosalux.de ISSN 2194-2242 · Redaktionsschluss: November 2019 Illustration Titelseite: Frank Ramspott/iStockphoto Lektorat: TEXT-ARBEIT, Berlin Layout/Herstellung: MediaService GmbH Druck und Kommunikation Gedruckt auf Circleoffset Premium White, 100 % Recycling Inhalt INHALT Vorwort. 4 Zusammenfassung. 5 Einleitung ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 6 Teil 1 Das Potenzial von YouTube -

1394 White Terrorism and Willful Ignorance

#1394 White Terrorism and Willful Ignorance JAY TOMLINSON - HOST, BEST OF THE LEFT: [00:00:00] During today's episode, I am going to be telling you about a new podcast I think you should check out. It's called Unf-ing the Republic, but they don't say f-ing. It'll help level up anyone's poliDcal arguing game. So hear me out mid-show, when I tell you more about it. And now, welcome to this episode of the award-winning Best of the LeI Podcast in which we shall learn about our long history of ignoring domesDc right-wing terrorism, from the Oklahoma City bombing through to the predictable acDons of miliDa groups in 2020 and beyond. Clips today are from the PBS News Hour, It's Been a Minute with Sam Sanders, Democracy Now!, AJ+, The David Pakman Show, the Washington Post, MSNBC and The Real News. Tracing the roots of the America's biggest domesKc terror aLack - PBS News Hour - Air Date 2-17-20 MAN: [00:00:47] There's heavy damage done. JEFFREY BROWN - HOST, PBS NEWSHOUR: [00:00:51] April 19, 1995. MAN: [00:00:56] About a third of the building has been blown away. JEFFREY BROWN - HOST, PBS NEWSHOUR: [00:00:56] A Ryder rental truck with 5,000 pounds of explosives ripped through the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City; 168 people were killed, 19 children among them. WOMAN: [00:01:08] Who has come in here and done this terrible thing? BARAK GOODMAN: [00:01:12] I knew very liale of the story. -

Unlikely Identities

Unlikely Identities: In May of 1911 an Ottoman deputy from Thessaloniki, Dimitar Vlahov, interjected Abu Ibrahim and the himself in a parliamentary debate about Zionism in Palestine with a question: “Are Politics of Possibility in 2 Arab peasants opposed to the Jews?” 1 Late Ottoman Palestine Answering himself, he declared that there was no enmity between Arab and Samuel Dolbee & Shay Hazkani Jewish peasants since, in his estimation, “They are brothers [onlar kardeştir], and like brothers they are trying to live.” Noting that in the past few weeks “anti- Semitism” had appeared on the pages of newspapers, he reiterated his message of familial bonds: “Whatever happens, the truth is in the open. Among Jewish, Arab, and Turkish peasants, there is nothing that will cause conflict. They are brothers.” Vlahov Efendi’s somewhat simplistic message of coexistence was not popular, appearing as it did in the midst of a charged debate about Zionist land acquisitions in Palestine.3 Other deputies in parliament pressed him about the source of his information on these apparent familial ties between peasants. He had mentioned “Arab newspapers,” but ʿAbd al-Mehdi Bey of Karbala wanted to know which ones he had consulted to support his claims. “In Jaffa there is a newspaper that appears named ‘Palestine,’” Vlahov replied. Commotion in the hall interrupted his speech at this point, but Vlahov continued, explaining how the paper suggested Hadera [Khdeira], south of Haifa, had been “nothing but wild animals” thirty years before but had recently become economically prosperous through Zionist settlement. Rishon LeZion, one of the first Zionist colonies, was another engine of development, as its tax revenue had increased a hundred- fold in the previous three decades, he claimed. -

The Armenian Genocide

The Armenian Genocide During World War I, the Ottoman Empire carried out what most international experts and historians have concluded was one of the largest genocides in the world's history, slaughtering huge portions of its minority Armenian population. In all, over 1 million Armenians were put to death. To this day, Turkey denies the genocidal intent of these mass murders. My sense is that Armenians are suffering from what I would call incomplete mourning, and they can't complete that mourning process until their tragedy, their wounds are recognized by the descendants of the people who perpetrated it. People want to know what really happened. We are fed up with all these stories-- denial stories, and propaganda, and so on. Really the new generation want to know what happened 1915. How is it possible for a massacre of such epic proportions to take place? Why did it happen? And why has it remained one of the greatest untold stories of the 20th century? This film is made possible by contributions from John and Judy Bedrosian, the Avenessians Family Foundation, the Lincy Foundation, the Manoogian Simone Foundation, and the following. And others. A complete list is available from PBS. The Armenians. There are between six and seven million alive today, and less than half live in the Republic of Armenia, a small country south of Georgia and north of Iran. The rest live around the world in countries such as the US, Russia, France, Lebanon, and Syria. They're an ancient people who originally came from Anatolia some 2,500 years ago. -

Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Winter 12-19-2019 Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics Kendra Hansen [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the American Studies Commons, Education Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hansen, Kendra, "Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 239. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/239 This Project (696 or 796 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics A Plan B Project Proposal Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Kendra Rose Hansen In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language December, 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota Copyright 2019 Kendra Rose Hansen v Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my family. To my husband, Brian Hansen, for supporting me and encouraging me to keep going and for taking on a greater weight of the parental duties throughout my journey. To my children, Aidan, Alexa, and Ainsley, for understanding when Mom needed to be away at class or needed quiet time to work at home. -

Pewdiepie, Popularity, and Profitability

Pepperdine Journal of Communication Research Volume 8 Article 4 2020 The 3 P's: Pewdiepie, Popularity, and Profitability Lea Medina Pepperdine University, [email protected] Eric Reed Pepperdine University, [email protected] Cameron Davis Pepperdine University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/pjcr Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Medina, Lea; Reed, Eric; and Davis, Cameron (2020) "The 3 P's: Pewdiepie, Popularity, and Profitability," Pepperdine Journal of Communication Research: Vol. 8 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/pjcr/vol8/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Journal of Communication Research by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 21 The 3 P’s: Pewdiepie, Popularity, & Popularity Lea Medina Written for COM 300: Media Research (Dr. Klive Oh) Introduction Channel is an online prole created on the Felix Arvid Ul Kjellberg—more website YouTube where users can upload their aectionately referred to as Pewdiepie—is original video content to the site. e factors statistically the most successful YouTuber, o his channel that will be explored are his with a net worth o over $15 million and over relationships with the viewers, his personality, 100 million subscribers. With a channel that relationship with his wife, and behavioral has uploaded over 4,000 videos, it becomes patterns. natural to uestion how one person can gain Horton and Wohl’s Parasocial such popularity and prot just by sitting in Interaction eory states that interacting front o a camera. -

2020 Election Year Is an Opportunity for Transformational Change If We Embrace Our Power | Dissident Voice

4/26/2020 2020 Election Year Is an Opportunity for Transformational Change If We Embrace Our Power | Dissident Voice About DV Archives Donate Contact Us Submissions Books Links 2020 Election Year Is an Opportunity for Transformational Change If We Embrace Our Power by Kevin Zeese and Margaret Flowers / April 22nd, 2020 Although we do not tie our organizing to the election cycle, the 2020 election is an opportunity for the people to set the agenda for the 2020s. We need to show that whether Donald Trump or Joe Biden are elected, the people will rule from below. We need to build our power to demand the transformational we need. We are living in an opportune time, as has existed previously in the United States when many of the issues people have fought for have come to the forefront, but the two parties disregarded the people. Similar to the abolition movement in the 19th century and the progressive/socialist movement in the early 20th century, this is our moment in the 21st century for systemic changes that fundamentally alter our healthcare system, economy, foreign policy, environmental policy and more. As Kali Akuno of Cooperation Jackson said in our recent Clearing the FOG interview (available Monday), the right- wing is using this time to push through their agenda of corporate bailouts, deregulation, and worker exploitation. If the left doesn’t organize and counter this, the country will continue on its current destructive path. The changes we want won’t come from the top. Both corporate duopoly candidate’s priorities are the wealthy investor class and big business. -

True Conservative Or Enemy of the Base?

Paul Ryan: True Conservative or Enemy of the Base? An analysis of the Relationship between the Tea Party and the GOP Elmar Frederik van Holten (s0951269) Master Thesis: North American Studies Supervisor: Dr. E.F. van de Bilt Word Count: 53.529 September January 31, 2017. 1 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Page intentionally left blank 2 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Table of Content Table of Content ………………………………………………………………………... p. 3 List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………. p. 5 Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………..... p. 6 Chapter 2: The Rise of the Conservative Movement……………………….. p. 16 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 16 Ayn Rand, William F. Buckley and Barry Goldwater: The Reinvention of Conservatism…………………………………………….... p. 17 Nixon and the Silent Majority………………………………………………….. p. 21 Reagan’s Conservative Coalition………………………………………………. p. 22 Post-Reagan Reaganism: The Presidency of George H.W. Bush……………. p. 25 Clinton and the Gingrich Revolutionaries…………………………………….. p. 28 Chapter 3: The Early Years of a Rising Star..................................................... p. 34 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 34 A Moderate District Electing a True Conservative…………………………… p. 35 Ryan’s First Year in Congress…………………………………………………. p. 38 The Rise of Compassionate Conservatism…………………………………….. p. 41 Domestic Politics under a Foreign Policy Administration……………………. p. 45 The Conservative Dream of a Tax Code Overhaul…………………………… p. 46 Privatizing Entitlements: The Fight over Welfare Reform…………………... p. 52 Leaving Office…………………………………………………………………… p. 57 Chapter 4: Understanding the Tea Party……………………………………… p. 58 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 58 A three legged movement: Grassroots Tea Party organizations……………... p. 59 The Movement’s Deep Story…………………………………………………… p. -

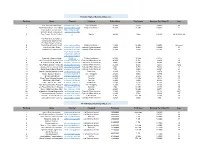

Sources & Data

YouTube Highest Earning Influencers Ranking Name Channel Category Subscribers Total views Earnings Per Video ($) Age 1 JoJo https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCeV2O_6QmFaaKBZHY3bJgsASiwa (Its JoJo Siwa) Life / Vlogging 10.6M 2.8Bn 569112 16 2 Anastasia Radzinskayahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJplp5SjeGSdVdwsfb9Q7lQ (Like Nastya Vlog) Children's channel 48.6M 26.9Bn 546549 6 Coby Cotton; Cory Cotton; https://www.youtube Garrett Hilbert; Cody Jones; .com/user/corycotto 3 Tyler Toney. (Dude Perfect) n Sports 49.4M 10Bn 186783 30,30,30,33,28 FunToys Collector Disney Toys ReviewToys Review ( FunToys Collector Disney 4 Toys ReviewToyshttps://www.youtube.com/user/DisneyCollectorBR Review) Children's channel 11.6M 14.9Bn 184506 Unknown 5 Jakehttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCcgVECVN4OKV6DH1jLkqmcA Paul (Jake Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 19.8M 6.4Bn 180090 23 6 Loganhttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCG8rbF3g2AMX70yOd8vqIZg Paul (Logan Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 20.5M 4.9Bn 171396 24 https://www.youtube .com/channel/UChG JGhZ9SOOHvBB0Y 7 Ryan Kaji (Ryan's World) 4DOO_w Children's channel 24.1M 36.7Bn 133377 8 8 Germán Alejandro Garmendiahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZJ7m7EnCNodqnu5SAtg8eQ Aranis (German Garmendia) Comedy / Entertainment 40.4M 4.2Bn 81489 29 9 Felix Kjellberg (PewDiePie)https://www.youtube.com/user/PewDiePieComedy / Entertainment 103M 24.7Bn 80178 30 10 Anthony Padilla and Ian Hecoxhttps://www.youtube.com/user/smosh (Smosh) Comedy / Entertainment 25.1M 9.3Bn 72243 32,32 11 Olajide William Olatunjihttps://www.youtube.com/user/KSIOlajidebt