Emily Lawless's with Essex in Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Búrca Rare Books

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 141 Spring 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 141 Spring 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Pennant is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 141: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our front and rear cover is illustrated from the magnificent item 331, Pennant's The British Zoology. -

But the Irish Sea Betwixt Us: Ireland, Colonialism, and Renaissance Literature

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, British Isles English Language and Literature 1999 But the Irish Sea Betwixt Us: Ireland, Colonialism, and Renaissance Literature Andrew Murphy University of St. Andrews Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Murphy, Andrew, "But the Irish Sea Betwixt Us: Ireland, Colonialism, and Renaissance Literature" (1999). Literature in English, British Isles. 16. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_british_isles/16 Irish Literature, History, & Culture Jonathan Allison, General Editor Advisory Board George Bornstein, University of Michigan Elizabeth Butler Cullingford, University of Texas James S. Donnelly Jr., University of Wisconsin Marianne Elliott, University of Liverpool Roy Foster, Hertford College, Oxford David Lloyd, University of California, Berkeley Weldon Thornton, University of North Carolina This page intentionally left blank But the Irish Sea Betwixt Us Ireland, Colonialisn1, and Renaissance Literature Andrew Murphy THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1999 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2009 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. -

Download (2MB)

Table of Contents Introduction Literary Context and Critical Background Page 1 Political Hinterland Page 5 Literary Hinterland Page 13 From the Historical to the Contemporary: Shifts in Perspective Page 20 Modern Critical Receptions Page 25 Lawless, Fiction and Socialization Page 39 Chapter I Hurrish: Representations of Violence through Character and Landscape Political and Literary Context Page 50 An Iron Land Page 62 Ideology and its Characteristics Page 71 Character and Landscape Page 79 Common Victims: Hurrish, Maurice and Alley Page 86 Patriotism and Nationalism Page 91 Peasant Squalor and Individual Human Value Page 96 Hurrish as Social Critique Page 103 Narratives of the Self: A Comparative Reading of Hurrish and A Drama in Muslin Page 108 Chapter II Historical Fiction Part I. With Essex in Ireland The Personal in History Page 117 Romance and Anti-Romance Page 126 Ideology and Revelation Page 138 The Feminine: Mistress, Mother and Crone Page 144 Narrative Form and Textual Experience Page 153 Chapter III Grania: Darwinism Biological Variation and New Woman Page 166 Darwinism and Literature Page 171 The Novel‟s Opening: Adapting to Environment Page 180 Stock and Pedigree: Honor and Grania Page 185 Stock and Pedigree: Murdough and Grania Page 192 Individual Promise and Social Revelation Page 201 The Struggle for Self-Assertion Page 209 Degeneration: Individual and Communal Page 222 Chapter IV Historical Fiction Part II. Maelcho National Tale and Historical Novel Page 234 Fiction and Stadialism Page 240 Temporal Otherness Page 254 Racial Theory: Lawless and Contemporary Discourse Page 266 Historical Realism: Fiction and Historiography Page 277 Conclusion Lawless and Subjectivity Page 286 Socialization and Alienation in Lawless Page 295 Bibliography Page 304 For my mother Brigid Stewart Prunty. -

Book Three Chapter Four

BOOK THREE CHAPTER FOUR This chapter of Book Three will begin at 1360 A. D., which was that period of Irish history where the Normans who had invaded Ireland at its southern extremities, and expanded their conquests northerly, were attempting to consolidate their successes. The Norman forces had been followed by King Henry II and his large army, who arrived to complete their establishment of the English foothold into Ireland, and to expand it through confiscation of Irish lands to other parts of the country, mainly through grants of large parcels of land with the understanding that the grantees had to conquer any existing Irish occupants of those parcels, and continue to hold those grants of land against any attempts by the former occupants to get it back. The chapter will extend forward to about 1587A. D., which is the time when the English forces kidnapped and imprisoned the fifteen year old child who was heir to leadership of the O'Donnell clan of Tyrone. He would become their chief, and he would fight many battles against the Crown forces in Ireland. In 1338 A. D., the English had entered into The Hundred Years War with the French, and it would last until 1453 A. D. The war complicated things for Ireland. It eliminated any assistance that the Irish might have received from France, and it weakened the amount of control that England could exert over the Irish. In 1342 A. D., Laoiseach O'More was slain by one of his own people. At his death, the Lord Deputy Sir Roger Mortimer regained possession of Dunamase, and he fortified this former seat of the O'Mores of Leix to make it his center of control for the area. -

John Donne and the Conway Papers a Biographical and Bibliographical Study of Poetry and Patronage in the Seventeenth Century

John Donne and the Conway Papers A Biographical and Bibliographical Study of Poetry and Patronage in the Seventeenth Century Daniel Starza Smith University College London Supervised by Prof. H. R. Woudhuysen and Dr. Alison Shell ii John Donne and the Conway Papers A Biographical and Bibliographical Study of Poetry and Patronage in the Seventeenth Century This thesis investigates a seventeenth-century manuscript archive, the Conway Papers, in order to explain the relationship between the archive’s owners and John Donne, the foremost manuscript poet of the century. An evaluation of Donne’s legacy as a writer and thinker requires an understanding of both his medium of publication and the collectors and agents who acquired and circulated his work. The Conway Papers were owned by Edward, first Viscount Conway, Secretary of State to James I and Charles I, and Conway’s son. Both men were also significant collectors of printed books. The archive as it survives, mainly in the British Library and National Archives, includes around 300 literary manuscripts ranging from court entertainments to bawdy ballads. This thesis fully evaluates the collection as a whole for the first time, including its complex history. I ask three principal questions: what the Conway Papers are and how they were amassed; how the archive came to contain poetry and drama by Donne, Ben Jonson, Thomas Middleton and others; and what the significance of this fact is, both in terms of seventeenth-century theories about politics, patronage and society, and modern critical and historical interpretations. These questions cast new light on the early transmission of Donne’s verse, especially his Satires and verse epistles. -

Prominent Elizabethans

Prominent Elizabethans. p.1: Church; p.2: Law Officers. p.3: Miscellaneous Officers of State. p.5: Royal Household Officers. p.7: Privy Councillors. p.9: Peerages. p.11: Knights of the Garter and Garter ceremonies. p.18: Knights: chronological list; p.22: alphabetical list. p.26: Knights: miscellaneous references; Knights of St Michael. p.27-162: Prominent Elizabethans. Church: Archbishops, two Bishops, four Deans. Dates of confirmation/consecration. Archbishop of Canterbury. 1556: Reginald Pole, Archbishop and Cardinal; died 1558 Nov 17. Vacant 1558-1559 December. 1559 Dec 17: Matthew Parker; died 1575 May 17. 1576 Feb 15: Edmund Grindal; died 1583 July 6. 1583 Sept 23: John Whitgift; died 1604. Archbishop of York. 1555: Nicholas Heath; deprived 1559 July 5. 1560 Aug 8: William May elected; died the same day. 1561 Feb 25: Thomas Young; died 1568 June 26. 1570 May 22: Edmund Grindal; became Archbishop of Canterbury 1576. 1577 March 8: Edwin Sandys; died 1588 July 10. 1589 Feb 19: John Piers; died 1594 Sept 28. 1595 March 24: Matthew Hutton; died 1606. Bishop of London. 1553: Edmund Bonner; deprived 1559 May 29; died in prison 1569. 1559 Dec 21: Edmund Grindal; became Archbishop of York 1570. 1570 July 13: Edwin Sandys; became Archbishop of York 1577. 1577 March 24: John Aylmer; died 1594 June 5. 1595 Jan 10: Richard Fletcher; died 1596 June 15. 1597 May 8: Richard Bancroft; became Archbishop of Canterbury 1604. Bishop of Durham. 1530: Cuthbert Tunstall; resigned 1559 Sept 28; died Nov 18. 1561 March 2: James Pilkington; died 1576 Jan 23. 1577 May 9: Richard Barnes; died 1587 Aug 24. -

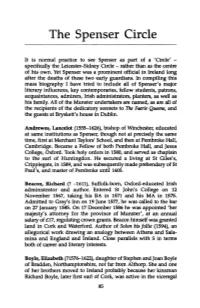

The Spei1ser Circle

The SpeI1Ser Circle It is normal practice to see Spenser as part of a 'Circle' - specifically the Leicester-Sidney Circle - rather than as the centre of his own. Yet Spenser was a prominent official in Ireland long after the deaths of these two early guardians. In compiling this mass biography I have tried to include all of Spenser' s major literary influences, key contemporaries, fellow students, patrons, acquaintances, admirers, Irish administrators, planters, as weIl as his family. All of the Munster undertakers are named, as are all of the recipients of the dedicatory sonnets to The Faerie Queene, and the guests at Bryskett's house in Dublin. Andrewes, Lancelot (1555-1626), bishop of Wmchester, educated at same institutions as Spenser, though not at precisely the same time, first at Merchant Taylors' SchooI, and then at Pembroke Hall, Cambridge. Became a Fellow of both Pembroke Hall, and Jesus College, Oxford. Took holy orders in 1580, and served as chaplain to the earl of Huntingdon. He secured a living at St Giles' s, Cripplegate, in 1589, and was subsequently made prebendary of St PauI's, and master of Pembroke until 1605. Beacon, Richard (? -1611), Suffolk-bom, Oxford-educated Irish administrator and author. Entered St John' s College on 12 November 1567, taking his BA in 1571 and his MA in 1575. Admitted to Gray's Inn on 19 June 1577, he was called to the bar on 27 January 1585. On 17 December 1586 he was appointed 'her majesty' s attomey for the province of Munster', at an annual salary of f:17, regulating crown grants. -

One of Many: Martial Law and English Laws C. 1500 – C. 1700 John

One of Many: Martial Law and English Laws c. 1500 – c. 1700 John Michael Collins Minneapolis, MN Bachelor of Arts, with honors, Northwestern University, 2006 MPHIL, with distinction, Cambridge University, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August 2013 Abstract This dissertation provides the first history of martial law in the early modern period. It seeks to reintegrate martial law in the larger history of English law. It shows how jurisdictional barriers constructed by the makers of the Petition of Right Parliament for martial law unintentionally transformed the concept from a complementary form of criminal law into an all-encompassing jurisdiction imposed by governors and generals during times of crisis. Martial law in the early modern period was procedure. The Tudor Crown made it in order to terrorize hostile populations into obedience and to avoid potential jury nullification. The usefulness of martial law led Crown deputies in Ireland to adapt martial law procedure to meet the legal challenges specific to their environment. By the end of the sixteenth century, Crown officers used martial law on vagrants, rioters, traitors, soldiers, sailors, and a variety of other wrongs. Generals, meanwhile, sought to improve the discipline within their forces in order to better compete with their rivals on the European continent. Over the course of the seventeenth century, owing to this desire, they transformed martial law substance, procedure, and administration. The usefulness of martial law made many worried, and MPs in 1628 sought to restrain martial law to a state of war, defined either as the Courts of Westminster being closed or by the presence of the enemy’s army with its standard raised. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Savagery and the State: Incivility and America in Jacobean Political Discourse WORKING, LAUREN,NOEMIE How to cite: WORKING, LAUREN,NOEMIE (2015) Savagery and the State: Incivility and America in Jacobean Political Discourse, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11350/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Savagery and the State: Incivility and America in Jacobean Political Discourse Lauren Working This thesis examines the effects of colonisation on the politics and culture of Jacobean London. Through sources ranging from anti-tobacco polemic to parliament speeches, colonial reports to private diaries, it contends that the language of Amerindian savagery and incivility, shared by policy-makers, London councillors, and colonists alike, became especially relevant to issues of government and behaviour following the post-Reformation state’s own emphasis on civility as a political tool. -

Modern Irish Poets and Their Elizabethan Predecessors

Difficult Ancestors: Modern Irish Poets and Their Elizabethan Predecessors Rui Carvalho Homem UNIVERSIDADE DO PORTO [email protected] It has in recent years become something of a critical commonplace to point out the extent to which both the strengths and weaknesses of modern Irish poetry can be linked to a persistent awareness of predecessors. That awareness helps account for the totemic value which a term like ‘tradition’ has long acquired in Irish critical discourse; it underlies the critical vindication of ‘intertextuality’ as a ‘natural’ condition of Irish literature (Longley 1990: 26); and, insofar as it is often experienced as constraint, limitation, or as a source of anxiety, it has led to suggestions that a Harold Bloomian notion of influence might find its ‘natural’ laboratory in a particularly convoluted Irish poetic tradition (Brown and Grene 1989: passim; Longley 1996: passim; Homem 1996: 175-177). This relational pattern of literary descent has proved easier to identify in the play of desired and spurned parental and filial relationships which characterises much of twentieth-century Irish literature –and in particular in the attitude of several authors towards Yeats and Joyce as alternative father- figures. Such quests for identity have, of course, marked political and cultural implications, rather than being a mere search for a sense of personal belonging in a literary lineage. But, thus understood, the relationship established to other and more remote predecessors may also prove enlightening –as I hope to demonstrate in this paper, concerned as it will be with the representation of sixteenth-century English poets in twentieth-century Irish poems. -

The Elizabethan Court Day by Day--1600

1600 1600 At RICHMOND PALACE, Surrey Jan 1,Tues New Year gifts. Among 197 gifts to the Queen: by Francis Bacon: ‘One petticoat of white satin embroidered all over like feathers and billets with three broad borders fair embroidered with snakes and fruitage’; by George Bishop, stationer: ‘Two books of Titus Livius in French’; by William Dethick, Garter King of Arms: ‘One book of Heraldry of the Knights of the Order this year’.NYG Earl and Countess of Rutland gave £20 in gold, and the same to ‘young Lady Walsingham of the Bedchamber’; gilt cup to the Lord Keeper, gilt bowls to ‘two chief judges’, and Mrs Mary Radcliffe. ‘To her Majesty’s Guard, 40s; the Porters and their men, 25s; Pantry, 25s; Buttery, 25s; Cellar, 25s; Spicery, 31s; Pages, 25s; Grooms ordinary, 13s4d; Extraordinary, 12s6d; Privy Kitcheners, 6s; Black Guard, 5s; Keeper of the Council Chamber door, 6s; Harbingers, 10s’.RT(4) Also Jan 1: play, by Admiral’s Men.T Thomas Dekker’s Shoemaker’s Holiday. Dekker’s play was printed, 1600, as ‘The Shoemaker’s Holiday. Or The Gentle Craft. With the humorous life of Simon Eyre, shoemaker, and Lord Mayor of London. As it was acted before the Queen’s most excellent Majesty on New Year’s Day at night last’. An Epistle ‘To all good Fellows’ presents ‘a merry conceited comedy...acted by my Lord Admiral’s Players this present Christmas before the Queen’s most excellent Majesty, for the mirth and pleasant matter by her Highness graciously accepted; being indeed in no way offensive’. -

The Elizabethan Court Day by Day--1599

1599 1599 At WHITEHALL PALACE. Jan 1,Mon New Year gifts. Among 195 gifts to the Queen: by Francis Bacon: ‘Two pendants of gold garnished with sparks of opals and each having three opals pendant’; by George Bishop, stationer: ‘Two books of Pliny’s Works in French’; by William Cordell, Master Cook: ‘One marchpane [marzipan] with the Queen’s Arms in the midst’; by William Dethick, Garter King of Arms: ‘One Book of Arms covered with crimson velvet’; by Petruccio Ubaldini: ‘A table with a picture and a book in Italian’.NYG Also Jan 1: play, by Lord Chamberlain’s Men.T Court news. Jan 3, London, John Chamberlain to Dudley Carleton ‘attending on the Lord Governor of Ostend’ (Sir Edward Norris): ‘The wind is come about again for Ireland’ and the Earl of Essex ‘prepares with all diligence and hath £12,000 delivered him to raise five or six hundred horse’.CHA Jan 6,Sat Danish Ambassador at Whitehall with the Queen. Dr Nicolas Krag, who related in his Diary that the Queen apologised, unnecess- arily, for her conversational Latin. The Earl of Essex invited her to dance; she at first declined, but later laughingly accepted, saying that she was doing in honour of the Ambassador what she had given up for many years, and told him to report to his King that she was not decrepit. [HMC 45th Report]. Also Jan 6: play, by Admiral’s Men.T (See note, 27 Dec 1598). Jan 8,Mon visit, St James’s Park, Westminster; Lady Burgh. St James’s Park house.