The Welsh in Ireland, 1558-1641

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Antiphonary of Bangor and Its Musical Implications

The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications by Helen Patterson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Helen Patterson 2013 The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications Helen Patterson Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines the hymns of the Antiphonary of Bangor (AB) (Antiphonarium Benchorense, Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana C. 5 inf.) and considers its musical implications in medieval Ireland. Neither an antiphonary in the true sense, with chants and verses for the Office, nor a book with the complete texts for the liturgy, the AB is a unique Irish manuscript. Dated from the late seventh-century, the AB is a collection of Latin hymns, prayers and texts attributed to the monastic community of Bangor in Northern Ireland. Given the scarcity of information pertaining to music in early Ireland, the AB is invaluable for its literary insights. Studied by liturgical, medieval, and Celtic scholars, and acknowledged as one of the few surviving sources of the Irish church, the manuscript reflects the influence of the wider Christian world. The hymns in particular show that this form of poetical expression was significant in early Christian Ireland and have made a contribution to the corpus of Latin literature. Prompted by an earlier hypothesis that the AB was a type of choirbook, the chapters move from these texts to consider the monastery of Bangor and the cultural context from which the manuscript emerges. As the Irish peregrini are known to have had an impact on the continent, and the AB was recovered in ii Bobbio, Italy, it is important to recognize the hymns not only in terms of monastic development, but what they reveal about music. -

“Éire Go Brách” the Development of Irish Republican Nationalism in the 20Th Into the 21St Centuries

“Éire go Brách” The Development of Irish Republican Nationalism in the 20th into the 21st Centuries Alexandra Watson Honors Thesis Dr. Giacomo Gambino Department of Political Science Spring 2020 Watson 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Literature Review: Irish Nationalism -- What is it ? 5 A Brief History 18 ‘The Irish Question’ and Early Roots of Irish Republicanism 20 Irish Republicanism and the War for Independence 25 The Anglo Irish Treaty of 1921, Pro-Treaty Republicanism vs. Anti-Treaty Republicanism, and Civil War 27 Early Statehood 32 ‘The Troubles’ and the Good Friday Agreement 36 Why is ‘the North’ Different? 36 ‘The Troubles’ 38 The Good Friday Agreement 40 Contemporary Irish Politics: Irish Nationalism Now? 45 Explaining the Current Political System 45 Competing nationalisms Since the Good Friday Agreement and the Possibility of Unification 46 2020 General Election 47 Conclusions 51 Appendix 54 Acknowledgements 57 Bibliography 58 Watson 3 Introduction In June of 2016, the people of the United Kingdom democratically elected to leave the European Union. The UK’s decision to divorce from the European Union has brought significant uncertainty for the country both in domestic and foreign policy and has spurred a national identity crisis across the United Kingdom. The Brexit negotiations themselves, and the consequences of them, put tremendous pressure on already strained international relationships between the UK and other European countries, most notably their geographic neighbour: the Republic of Ireland. The Anglo-Irish relationship is characterized by centuries of mutual antagonism and the development of Irish national consciousness, which ultimately resulted in the establishment of an autonomous Irish free state in 1922. -

Gwydir Family

THE HISTORY OF THE GWYDIR FAMILY, WRITTEN BY SIR JOHN WYNNE, KNT. AND BART., UT CREDITUR, & PATET. OSWESTRY: \VOODJ\LL i\KD VENABLES, OS\VALD ROAD. 1878. WOODALL AND VENABLES, PRINTERS, BAILEY-HEAD AND OSWALD-ROAD. OSWESTRY. TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE CLEMENTINA ELIZABETH, {!N HER OWN lHGHT) BARONESS WILLOUGHBY DE ERESBY, THE REPRESENTATIVE OF 'l'HE OLD GWYDIR STOCK AND THE OWNER OF THE ESTATE; THE FOURTEENTH WHO HAS BORNE THAT ANCIENT BARONY: THIS EDITION OF THE HISTORY OF THE GWYDIR FAMILY IS, BY PERMISSION, RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY THE PUBLISHERS. OSWALD ROAD, OSWESTRY, 1878. PREFACE F all the works which have been written relating to the general or family history O of North Wales, none have been for centuries more esteemed than the History of the Gwydir Family. The Hon. Daines Barrington, in his preface to his first edition of the work, published in 1770, has well said, "The MS. hath, for above.a cent~ry, been so prized in North Wales, that many in those parts have thought it worth while to make fair and complete transcripts of it." Of these transcripts the earliest known to exist is one in the Library at Brogyntyn. It was probably written within 45 years of the death of the author; but besides that, it contains a great number of notes and additions of nearly the same date, which have never yet appeared in print. The History of the Gwydir Family has been thrice published. The first editiun, edited by the Hon. Daines Barrington, issued from the press in 1770. The second was published in Mr. -

Intermarriage and Other Families This Page Shows the Interconnection

Intermarriage and Other Families This page shows the interconnection between the Townsend/Townshend family and some of the thirty-five families with whom there were several marriages between 1700 and 1900. It also gives a brief historical background about those families. Names shown in italics indicate that the family shown is connected with the Townsend/Townshend elsewhere. Baldwin The Baldwin family in Co Cork traces its origins to William Baldwin who was a ranger in the royal forests in Shropshire. He married Elinor, daughter of Sir Edward Herbert of Powys and went to Ireland in the late 16th century. His two sons settled in the Bandon area; the eldest brother, Walter, acquired land at Curravordy (Mount Pleasant) and Garrancoonig (Mossgrove) and the youngest, Thomas, purchased land at Lisnagat (Lissarda) adjacent to Curravordy. Walter’s son, also called Walter, was a Cromwellian soldier and it is through his son Herbert that the Baldwin family in Co Cork derives. Colonel Richard Townesend [100] Herbert Baldwin b. 1618 d. 1692 of Curravordy Hildegardis Hyde m. 1670 d. 1696 Mary Kingston Marie Newce Horatio Townsend [104] Colonel Bryan Townsend [200] Henry Baldwin Elizabeth Becher m. b. 1648 d. 1726 of Mossgrove 1697 Mary Synge m. 13 May 1682 b. 1666 d. 1750 Philip French = Penelope Townsend [119] Joanna Field m. 1695 m. 1713 b. 1697 Elizabeth French = William Baldwin John Townsend [300] Samuel Townsend [400] Henry Baldwin m. 1734 of Mossgrove b. 1691 d. 1756 b.1692 d. 1759 of Curravordy b.1701 d. 1743 Katherine Barry Dorothea Mansel m. 1725 b. 1701 d. -

De Búrca Rare Books

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 141 Spring 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 141 Spring 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Pennant is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 141: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our front and rear cover is illustrated from the magnificent item 331, Pennant's The British Zoology. -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

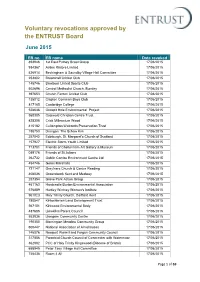

Voluntary Revocations Approved by the ENTRUST Board

Voluntary revocations approved by the ENTRUST Board June 2015 EB no. EB name Date revoked 893946 1st East Putney Scout Group 17/06/2015 934367 Action Kintore Limited 17/06/2015 426914 Beckingham & Saundby Village Hall Committee 17/06/2015 253802 Broomhall Cricket Club 17/06/2015 148746 Broxburn United Sports Club 17/06/2015 502696 Central Methodist Church, Burnley 17/06/2015 397653 Church Fenton Cricket Club 17/06/2015 135012 Clapton Common Boys Club 17/06/2015 817165 Coatbridge College 17/06/2015 528636 Cockpit Hole Environmental Project 17/06/2015 560305 Cotswold Christian Centre Trust 17/06/2015 428308 Crick Millennium Wood 17/06/2015 415182 Cullompton Walronds Preservation Trust 17/06/2015 198753 Drongan: The Schaw Kirk 17/06/2015 257042 Edinburgh, St. Margaret's Church of Scotland 17/06/2015 157927 Electric Storm Youth Limited 17/06/2015 713701 Friends of Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum 17/06/2015 089176 Friends of St Julians 17/06/2015 262732 Goblin Combe Environment Centre Ltd 17/06/2015 454746 Gores Marshalls 17/06/2015 721147 Greyfriars Church & Centre Reading 17/06/2015 408036 Groundwork Kent and Medway 17/06/2015 257354 Grove Park Action Group 17/06/2015 461163 Hardcastle Burton Environmental Association 17/06/2015 576889 Hartley Wintney Women's Institute 17/06/2015 961023 Holy Trinity Church, Dartford Kent 17/06/2015 780547 Kinlochleven Land Development Trust 17/06/2015 567101 Kirkwood Environmental Body 17/06/2015 487685 Limekilns Parent Council 17/06/2015 553836 Llangwm Community Centre 17/06/2015 190350 Mornington Meadow -

Genre and Identity in British and Irish National Histories, 1541-1691

“NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 A dissertation presented by Sarah Elizabeth Connell to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2014 1 “NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 by Sarah Elizabeth Connell ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2014 2 ABSTRACT In this project, I build on the scholarship that has challenged the historiographic revolution model to question the valorization of the early modern humanist narrative history’s sophistication and historiographic advancement in direct relation to its concerted efforts to shed the purportedly pious, credulous, and naïve materials and methods of medieval history. As I demonstrate, the methodologies available to early modern historians, many of which were developed by medieval chroniclers, were extraordinary flexible, able to meet a large number of scholarly and political needs. I argue that many early modern historians worked with medieval texts and genres not because they had yet to learn more sophisticated models for representing the past, but rather because one of the most effective ways that these writers dealt with the political and religious exigencies of their times was by adapting the practices, genres, and materials of medieval history. I demonstrate that the early modern national history was capable of supporting multiple genres and reading modes; in fact, many of these histories reflect their authors’ conviction that authentic past narratives required genres with varying levels of facticity. -

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard)

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard) Friday 29 June 2012 Volume 76, No WA2 This publication contains the written answers to questions tabled by Members. The content of the responses is as received at the time from the relevant Minister or representative of the Assembly Commission and has not been subject to the official reporting process or changed in any way. Contents Written Answers to Questions Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister ............................................................... WA 193 Department of Agriculture and Rural Development .................................................................. WA 195 Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure ................................................................................ WA 199 Department of Education ...................................................................................................... WA 204 Department for Employment and Learning .............................................................................. WA 219 Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment .................................................................... WA 222 Department of the Environment ............................................................................................. WA 222 Department of Finance and Personnel ................................................................................... WA 244 Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety ......................................................... WA 253 Department -

My “Brick Wall”

My “Brick Wall” The search for my paternal great, great grandfather “William Flack, a Soldier”. By Dr Edmund (known as “Ted”) Flack. BEc., PhD., JP (Qual) My “Brick Wall” in the search for my paternal great great grandfather. In this report I set out the evidence gathered over the last 20 years in my search to identify my great great grandfather, William Flack, the father of Captain William “Billy” Flack. First, I reproduce a paternal pedigree showing my relationship with Billy Flack and his relationship with his father William Flack, and his mother, Elizabeth Flack, born about 1790 in Ireland. A separate report on the life of Captain William Flack born 1 April 1810 is available. For the purpose of clarity, I will refer to my Great Grandfather, Captain William Flack as “Billy”. 1 What do we know about Billy Flack’s parents? There are three pieces of documentary evidence that provide the basis for the search as follows: 1. The first is Billy Flack’s original enlistment documents created when he enlisted in the 63rd Regiment of Foot in Bailieborough, County Cavan, Ireland on 17th February 1831. In that document it records 782 Pte William Flack as 21 years old, born in “the Parish of Killan in or near the town of Balyburrow in the County of Cavan”. Note 1. It will noted that Billy Flack signed the document with his “X” mark, indicating that he could probably not read or write and that therefore the recruiting sergeant probably filled in the details by recording Billy Flack’s verbal answers to this questions about age and place of birth. -

249 Nathalie Rougier and Iseult Honohan CHAPTER 10. Ireland

CHAPTER 10. IRELAND Nathalie Rougier and Iseult Honohan School of Politics and International Relations, University College Dublin Introduction Ireland’s peripheral position has historically often delayed the arrival of waves of social and cultural change in other parts of Europe. Part of its self-identity has derived from the narrative of its having been as a refuge for civilisation and Christianity during the invasions of what were once known as the ‘dark ages’, when it was described as ‘the island of saints and scholars’. Another part derives from its history of invasion, settlement and colonisation and, more specifically from its intimate relationship with Great Britain. The Republic of Ireland now occupies approximately five-sixths of the island of Ireland but from the Act of Union in 1800 until 1922, all of the island of Ireland was effectively part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ire- land. The war of Independence ended with the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, and on 6 December 1922 the entire island of Ireland became a self-governing British dominion called the Irish Free State (Saorstát Éireann). Northern Ire- land chose to opt out of the new dominion and rejoined the United King- dom on 8 December 1922. In 1937, a new constitution, the Constitution of Ireland (Bunreacht na hÉireann), replaced the Constitution of the Irish Free State in the twenty-six county state, and called the state Ireland, or Éire in Irish. However, it was not until 1949, after the passage of the Republic of Ireland Act 1948, that the state was declared, officially, to be the Republic of Ireland (Garvin, 2005). -

Some Pioneer Families of Wisconsin

.. .... -. ,. .. ,. ......i ......- -- SOME PIONEER FAMILIES OF WISCONSIN - An Index - edited by Betty Patterson A Bicentennial Project of the Wisconsin State Genealogical Society, Inc. Madison, Wisconsin 1977 Copyright@1977, Wisconsin State Genealogical Society, Inc. Library of Congress Cata log Card No.: 77-11739 PUBLISHED BY THE WISCONSIN STATE c;:+ICAL SOCIETY INC. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY .•.• tht: PRINl'shop OF DIXON, ILLINOIS ' ' This little book is dedicated to those who have sensed the thrill of unraveling their family mystery stories and the quiet satisfaction that comes from traveling vicariously with generations of grandparents long unknown. It is hoped that, at least in Wisconsin, it may make their searching a little easier. ERRATA II p. 2, Line 31 should read: "Spelling was an imprecise art in times past, Line 38 should read: 11 Jorndt, while the other (Fern Smith, #1815 .... 11 p. 126, Lines 70, 71, & 72, the spouses in column 4 should be Ann Eliza Taylor, George J. Beach, and Edward L. Myers. Background of the Pioneer and Century Certificate Project Even before the impetus of the Bicentennial year and the appearance of Alex Haley's Roots, more and more people were becoming interested in genealogy. Fifty years ago, the word was apt to mean an exercise aimed at qualifying for membership in an exclusive society. Today, its meaning has broadened to acconnnodate an increased awareness of the value of family and national heritages. Realization has come, too, that in a time of great social change, the knowledge of these--placing the individual, as it were, in a context--can stabilize and illuminate the sense of self.