The Decline of Suicide in Sweden: 1950-2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romanian Journal of Psychiatry 01/2013; XV(2); 2

EDITORIAL BOARD Editor-in-chief: Dan PRELIPCEANU Co-editors: Dragoș MARINESCU Aurel NIREȘTEAN ASSOCIATE EDITORS Doina COZMAN Liana DEHELEAN Marieta GABOȘ GRECU Maria LADEA Cristinel ȘTEFĂNESCU Cătălina TUDOSE ROMANIAN Executive Editors: Elena CĂLINESCU Valentin MATEI STEERING COMMITTEE Vasile CHIRIȚĂ (Honorary Member of the Romanian Academy of Medical Sciences, Iasi) JOURNAL Michael DAVIDSON (Professor, Sackler School of Medicine Tel Aviv Univ., Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York) Virgil ENĂTESCU (Member of the Romanian Academy of Medical Sciences, Satu Mare) Ioana MICLUȚIA (UMF Cluj-Napoca) of Șerban IONESCU (Paris VIII University, Trois-Rivieres University, Quebec) Mircea LĂZĂRESCU (Honorary Member of the Romanian Academy of Medical Sciences, Timisoara) Juan E. MEZZICH (Professor of Psychiatry and Director, Division of Psychiatric Epidemiology and International Center PSYCHIATRY for Mental Health, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York) Teodor T. POSTOLACHE, MD (Director, Mood and Anxiety Program, Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore) Sorin RIGA (senior researcher, Obregia Hospital Bucharest) Dan RUJESCU (Head of Psychiatric Genomics and Neurobiology and of Division of Molecular and Clinical Neurobiology, Department of Psychiatry, Ludwig-Maximilians- University, Munchen) Eliot SOREL (George Washington University, Washington DC) Maria GRIGOROIU-ȘERBĂNESCU (senior researcher) Tudor UDRIȘTOIU (UMF Craiova) ROMANIAN ASSOCIATION OF PSYCHIATRY AND PSYCHOTHERAPY WPA 2015 Bucharest International Congress 24 - 27 June • Palace of the Parliament, Bucharest Lectures WPA 2015 Bucharest International Congress 24 - 27 June • Palace of the Parliament, Bucharest Mental Health, Primary Care and the Challenge of Universal Health Coverage Michael Kidd Flinders University, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Australia Objectives: Family doctors and the members of primary health care teams have the capacity to successfully diagnose and treat mental health disorders. -

Jack Hicks Suicide by Greenlandic Youth, in Historical and Circumpolar

Jack Hicks Suicide by Greenlandic youth, in historical and circumpolar perspective Meeqqat inuusuttullu Kalaallit Nunaanni - allaaserisat katersat The article is a part of the anthology Wolfgang Kahlig & Nina Banerjee (aaqq.) “Children and Youth in Greenland - an anthology” which was published in 2007 by MIPI, Ilisimatusarfik and MILIK Publishing. MIPI · Ilisimatusarfik · milik publishing Jack Hicks January 2007 Suicide by Greenlandic youth, in historical and circumpolar perspective ABSTRACT: Death by suicide appears to have occurred relatively infrequently in Greenland until the 1970s, when suicide rates began to increase dramatically among men born after 1950. The overall suicide rate for Greenlanders peaked at a rate of 125 per annum per 100,000 in 1986, then fell off to roughly 100 per annum per 100,000 population around 1990 - and has remained at or near that level ever since. The rate is much higher among younger men than it is among middle-aged or older men, or among women. Suicide rates among young men in Nuuk have declined significantly over the past 25 years, while they have risen considerably in East Greenland and remained stable on the rest of the west coast. This article presents a short summary of what is known (and not known, in a scientific way) about suicide by Greenlandic youth, and situates the present youth suicide situation in Greenland in historical and circumpolar perspective. Introductory notes The category ‘persons born in Greenland’ is employed in this article as a proxy for ‘Greenlanders’. Most of the statistical data on rates of death by suicide by Green- landers used in this article were developed by Dr. -

COVID-19 and Tele-Health, Effectiveness of Internet-Delivered

WCRJ 2021; 8: e2043 COVID-19 AND TELE-HEALTH, EFFECTIVENESS OF INTERNET-DELIVERED PARENT-CHILD INTERACTION THERAPY ON IMPULSIVITY INDEX IN CHILDREN WITH NON-METASTATIC CANCER PARENTS: A PILOT RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL P. SADEGHI1, G. MIRZAEI2, F. REZA2, Z. KHANJANI2, M. GOLESTANPOUR1, Z. NABAVIPOUR3, M. DASTANBOYEH4 1Department of Psychology, Tehran Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran 2Department of Clinical Psychology, Garmsar Branch, Islamic Azad University, Garmsar, Iran 3Department of Psychology, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran 4Department of Clinical Psychology, Karaj Branch, Islamic Azad University, Karaj, Iran Abstract – Objective: COVID-19 pandemic has had devastating effects on the psychological state of society and has made the importance of planning evidence-based interventions even more apparent. Despite advances in telecommunication technologies to facilitate access to psychological care, the use of this technology in psychology has been limited and few studies have been conduct- ed in this field. The present study is the first controlled trial of applying video-teleconferencing to use parent-child interaction therapy in Iranian society. Patients and Methods: In a pilot randomized controlled trial, during May to November 2020 and from families with a mother with non-metastatic cancer, 42 parents and children with oppo- sitional defiant disorder (ODD) were selected through purposive sampling method and were as- signed into two groups of internet-delivered parent-child interaction therapy (I-PCIT) and waiting list (WL). After three weeks of baseline evaluation, twelve weekly I-PCIT sessions were presented to the experimental group in the form of video-teleconferencing based on Landers and Bratton model. -

Suicide Research: Selected Readings. Volume 2

SuicideResearchText-Vol2:SuicideResearchText-Vol2 8/6/10 11:00 AM Page i SUICIDE RESEARCH: SELECTED READINGS Volume 2 May 2009–October 2009 J. Sveticic, K. Andersen, D. De Leo Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Suicide Prevention National Centre of Excellence in Suicide Prevention SuicideResearchText-Vol2:SuicideResearchText-Vol2 8/6/10 11:00 AM Page ii First published in 2009 Australian Academic Press 32 Jeays Street Bowen Hills Qld 4006 Australia www.australianacademicpress.com.au Reprinted in 2010 Copyright for the Introduction and Comments sections is held by the Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention, 2009. Copyright in all abstracts is retained by the current rights holder. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act, 1968, no part may be reproduced without prior permission from the Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention. ISBN: 978-1-921513-53-4 SuicideResearchText-Vol2:SuicideResearchText-Vol2 8/6/10 11:00 AM Page iii Contents Foreword ................................................................................................vii Acknowledgments ..............................................................................viii Introduction Context ..................................................................................................1 Methodology ........................................................................................2 Key articles Alexopoulos et al, 2009. Reducing suicidal ideation -

A Comparison Between the Age Patterns and Rates of Suicide in the Islamic Republic of Iran and Australia

Report EMHJ – Vol. 26 No. 6 – 2020 A comparison between the age patterns and rates of suicide in the Islamic Republic of Iran and Australia John Snowdon,1 Seyed Mehdi Saberi2 and Ehsan Moazen-Zadeh3,4 1Sydney Medical School and Concord Hospital, Sydney, Australia (Correspondence to: John Snowdon: [email protected]). 2Legal Medicine Research Centre, Legal Medicine Organization, Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran. 3Psychiatric Research Centre, Roozbeh Hospital and Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran. 4Institute of Mental Health, Department of Psychiatry, University of British Colum- bia, Vancouver, Canada. Abstract Background: When planning interventions aimed at preventing suicide, it is important to consider how socioeconomic and cultural factors may affect suicide rates. There has been variability in the accuracy of recording suicide deaths, lead- ing to varying levels of underestimation. Social, cultural and religious elements affect whether deaths resulting from suicide are reported as such and those responsible for reporting a death may avoid providing information that would suggest the death was due to suicide. Aims: The aim of this study was to document Iranian suicide patterns in 2006–2010 and 2011–2015, compare them with those in a “Western” country (Australia) and explore whether differences point to factors that affect suicide rates. Methods: Data were obtained from Iranian and Australian national statistics offices. Results: Peak Iranian male suicide rates were in young adulthood. There was a modest increase between the 2 quinquen- nials studied. Australian male rates were much higher, with age peaks in middle age and very late life. From age 30, the female rate was twice as high in Australia, graphs of the age patterns being relatively flat in both countries. -

Sweden Part 1

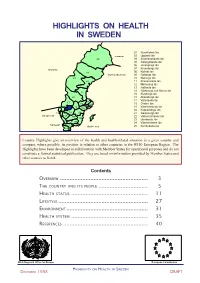

HIGHLIGHTS ON HEALTH IN SWEDEN 01 Stockholms län 03 Uppsala län Finland 25 04 Södermanlands län 05 Östergötlands län 06 Jönköpings län 07 Kronobergs län Norway 08 Kalmar län 24 Gulf of Bothnia 09 Gotlands län 23 10 Blekinge län 22 11 Kristianstads län 12 Malmöhus län 13 Hallands län 14 Göteborgs och Bohus län 21 15 Älvsborgs län 20 16 Skaraborgs län 17 Värmlands län 17 03 18 Örebro län 19 01 18 19 Västmanlands län 04 20 Kopparbergs län 14 16 05 21 Gävleborgs län Skagerrak 15 06 22 Västernorrlands län 08 09 23 Jämtlands län 13 07 24 Västerbottens län Kattegat 11 10 Baltic sea 25 Norrbottens län 12 Country Highlights give an overview of the health and health-related situation in a given country and compare, where possible, its position in relation to other countries in the WHO European Region. The Highlights have been developed in collaboration with Member States for operational purposes and do not constitute a formal statistical publication. They are based on information provided by Member States and other sources as listed. Contents OVERVIEW ....................................................... 3 THE COUNTRY AND ITS PEOPLE ............................... 5 HEALTH STATUS ................................................ 11 LIFESTYLE ........................................................ 27 ENVIRONMENT ................................................... 31 HEALTH SYSTEM ................................................ 35 REFERENCES ..................................................... 40 WHO Regional Office for Europe European Commission -

Trend of Suicide in Iran During 2009 to 2012

Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2016 December; 10(4):e4398. doi: 10.17795/ijpbs-4398. Published online 2016 October 30. Original Article Trend of Suicide in Iran During 2009 to 2012: Epidemiological Evidences from National Suicide Registration Ahmad Hajebi,1 Masoud Ahmadzad-Asl,2,* Farnoush Davoudi,3 and Raoofeh Ghayyomi2 1Research Center for Addiction and Risky Behaviors (ReCARB), Psychiatric Department, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran 2Mental Health Research Center, Tehran Psychiatry Institute, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran 3Department of Community Medicine, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran *Corresponding author: Masoud Ahmadzad-Asl, M.D., Psychiatrist, No.1, Mansuri St, Niayesh Ave., Sattarkhan Ave., Tehran, Iran. Tel/Fax: +98-2166556862, E-mail: [email protected] Received 2015 October 08; Revised 2015 November 15; Accepted 2016 October 22. Abstract Background: Suicide behaviors cause a large portion of Disability adjusted life years worldwide. Objectives: The aim of this research was to study the trend, correlations and discrepancy of registered suicide incidents in Iran from 2009 to 2012 using data from the Iranian suicide registry. Materials and Methods: Suicide registry entries throughout the country between 2009 and 2012, including suicidal attempts and suicides, were collected. Data on age, gender, occupational, marital and residential status along with suicide method, history of previous attempt and history of medical or mental disorders were registered by health service provision staff at the service centers. Geographic mapping and statistical analysis were performed. Results: Amongst the 252911 attempted suicides during the period, we found suicide attempt and suicide rate of 30.5 - 44.8 and 1.76 - 2.23 per 100000 individuals, respectively,denoting overall suicide fatality rate of 2.63%. -

Physician Suicide: a Scoping Literature Review to Highlight Opportunities for Prevention

GLOBAL PSYCHIATRY — Vol 3 | Issue 2 | 2020 Tiffany I. Leung, MD, MPH, FACP, FAMIA1*, Rebecca Snyder, MSIS2, Sima S. Pendharkar, MD, MPH, FACP3‡, Chwen-Yuen Angie Chen, MD, FACP, FASAM4‡ Physician Suicide: A Scoping Literature Review to Highlight Opportunities for Prevention 1Faculty of Health, Medicine, and Life Sciences, Department of Internal Medicine, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands 2Library Services, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA 3Division of Hospital Medicine, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Icahn School of Medicine Mt. Sinai, Brooklyn, NY, USA 4Department of Primary Care and Population Health, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, USA *email: [email protected] ‡Indicates equal contributions as last authors to the production of this manuscript. DOI: 10.2478/gp-2020-0014 Received: 27 February 2020; Accepted: 12 May 2020 Abstract Objective: The aim of this scoping review is to map the current landscape of published research and perspectives on physician suicide. Findings could serve as a roadmap for further investigations and potentially inform efforts to prevent physician suicide. Methods: Ovid MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Scopus were searched for English-language publications from August 21, 2017 through April 28, 2018. Inclusion criteria were a primary outcome or thesis focused on suicide (including suicide completion, attempts, and thoughts or ideation) among medical students, postgraduate trainees, or attending physicians. Opinion articles were included. Studies that were non-English or those that only mentioned physician burnout, mental health, or substance use disorders were excluded. Data extraction was performed by two authors. Results: The search yielded 1,596 articles, of which 347 articles passed to the full-text review round. -

A Survey of Suicide by Burning in Tehran, Iran

ORIGINAL REPORT A Survey of Suicide by Burning in Tehran, Iran Fakhredin Taghaddosinejad1, Ardeshir Sheikhazadi*1, Behnam Behnoush1, Jafar Reshadati2, and Seyed Hossein Sabery Anary3 1 Department of Legal Medicine, School of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran 2 Doctor of Criminal Law, Judge of Tehran's Judiciary Office, Tehran, Iran 3 Health Service Management, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran Received: 12 Aug. 2009; Received in revised form: 22 Sep, 2009; Accepted: 9 Oct. 2009 Abstract- To identify the characteristics of completed suicide by burning in Tehran. A retrospective analysis of data obtained from Tehran's Legal Medicine Organization and judiciary system over 5-years (from 2002 to 2006). During the 5 years, 374 decedents (64.2% female and 35.8% male) were diagnosed as suicide by self-burning, and the annual incidence rate was 0.9 per 100,000 general population-years. The most at risk group was young females. Sixty-five decedents (17.4%) had died at the scene of incidents. The location at the time of attempted suicide in all female victims and 75.4% of male decedents was home. Sixty-one percent of decedents were married and 26.2% of them had no education. Most victims were residents of suburban areas. The annual incidence rate of self-burning suicide in Tehran was found to be lower than other Iran's geographic areas, although it was higher than developed countries. Self-burning was more frequent in females than in males and was noted mainly in young age groups' residents of suburban areas with low level of education. -

Season of Birth in Suicidology

UMEÅ UNIVERSITY MEDICAL DISSERTATIONS New Series No. 604 ISSN 0346-6612 ISBN 91-7191-645-8. From the Division of Psychiatry, Department of Clinical Science, Umeå University, SE-901 85 Umeå, Sweden SEASON OF BIRTH IN SUICIDOLOGY Neurobiological and epidemiological studies Jayanti Chotai Umeå 1999 UMEÅ UNIVERSITY MEDICAL DISSERTATIONS New Series No. 604 ISSN 0346-6612 ISBN 91-7191-645-8. From the Division of Psychiatry, Department of Clinical Science, Umeå University, 901 85 Umeå, Sweden. SEASON OF BIRTH IN SUICIDOLOGY Neurobiological and epidemiological studies AKADEMISK AVHANDLING som med vederbörligt tillstånd av rektorsämbetet vid Umeå universitet for avläggande av medicine doktorsexamen kommer att offentligen försvaras i Sal B, 9 tr, Tandläkarhögskolan, Norrlands universitetssjukhus, Umeå, fredagen den 28 maj 1999, kl 13.00 av Jayanti Chotai 1 v. *5 <J> va Fak ultetsopponent: Professor Hans Ågren, Karolinska institutet, Sektionen för psykiatri, Huddinge sjukhus Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Medical Science in Psychiatry presented at Umeå University in 1999. ABSTRACT Chotai J (1999). Season of birth in suicidology: neu robiologies and epidemiological studies. Umeå University, Department of Clinical Science, Division of Psychiatry, 901 85 Umeå, Sweden. ISSN 0346-6612 ISBN 91-7191-645-8. Barkpround: Several neuropsychiatrie disorders have shown season of birth associations. Low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of the serotonin metabolite 5-HIAA and the dopamine metabolite HVA have been associated with suicidal behaviour, impulsivity, and aggression. This thesis investigated associations between the season of birth, the CSF levels of three monoamine metabolites (including MHPG of norepinephrine), the scales of the diagnostic interview for borderline patients (DIB), and psychiatric diagnoses. -

Unikkaartuit: Meanings and Experiences of Suicide Among Inuit in Nunavut, Canada REVISED REFERENCES, 04/13/2016

Suicide Among Inuit • Michael J. Kral, Lori Idlout, J. Bruce Minore, Ronald J. Dyck, Laurence J. Kirmayer Unikkaartuit: Meanings and Experiences of Suicide Among Inuit in Nunavut, Canada REVISED REFERENCES, 04/13/2016 Abstract Inuit in Arctic Canada have one of the highest suicide rates in the world. Most of these suicides occur among youth, especially males, between the ages of 15 and 24. The goal of this study was to gain an understanding of Inuit experiences with suicide and what suicide means to Inuit, including suicide attempters and bereaved survivors. Fifty Inuit between the ages of 14 and 94 were interviewed about suicides in two communities in Nunavut. Sixty-three high school and college students were also surveyed with the same questions. It was found that suicide was most closely related to romantic relationship and family problems, and to experiences of loneliness and anger. These findings are interpreted in the context of massive social change, on-going colonization, and multigenerational trauma following the colonial government era of the 1950s and 1960s, when family and interpersonal relationships were significantly affected. The study stresses that suicide prevention strategies focus on youth and family, particularly on parenting, and ensure that Inuit communities take control of prevention programs. It recommends that family and community resources be further mobilized for suicide prevention. Keywords Inuit, suicide, colonialism, trauma Authors Michael J. Kral, Wayne State University. Lori Idlout, Embrace Life Council. J. Bruce Minore, Lakehead University. Ronald J. Dyck, InovaWay Inc. Laurence J. Kirmayer, McGill University. Acknowledgements The communities of Igloolik and Qikiqtarjuaq are thanked for their valuable participation in this study. -

Socio-Demographic and Economics Factors Associated with Suicide

Haghparast-Bidgoli et al. International Journal for Equity in Health (2018) 17:77 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0794-0 RESEARCH Open Access Socio-demographic and economics factors associated with suicide mortality in Iran, 2001–2010: application of a decomposition model Hassan Haghparast-Bidgoli1* , Giulia Rinaldi2, Hossein Shahnavazi3, Hamid Bouraghi4 and Aliasghar A. Kiadaliri5 Abstract Background: Suicide is a major global health problem, especially among youth. Suicide is known to be associated with a variety of social, economic, political and religious factors, vary across geographical and cultural regions. The current study aimed to investigate the effects of socioeconomic factors on suicide mortality rate across different regions in Iran. Methods: The data on distribution of population and socio-economic factors (such as unemployment rate, divorce rate, urbanization rate, average household expenditure etc.) at province level were obtained from the Statistical Centre of Iran and the National Organization for Civil Registration. The data on the annual number of deaths caused by suicide in each province was extracted from the published reports of the Iranian Forensic Medicine Organization. We used a decomposition model to distinguish between spatial and temporal variation in suicide mortality. Results: The average rate of suicide mortality was 5.5 per 100,000 population over the study period. Across the provinces (spatial variation), suicide mortality rate was positively associated with household expenditure and the proportion of people aged 15–24 and older than 65 years and was negatively associated with the proportion of literate people. Within the provinces (temporal variation), higher divorce rate was associated with higher suicide mortality.